A fishing knot does infinitely more than bind a fly or lure or bait to line, it binds a person to the idea of catching a fish.

“It’s the tie that binds.” I wasn’t sure if he was making a statement to me or talking to himself.

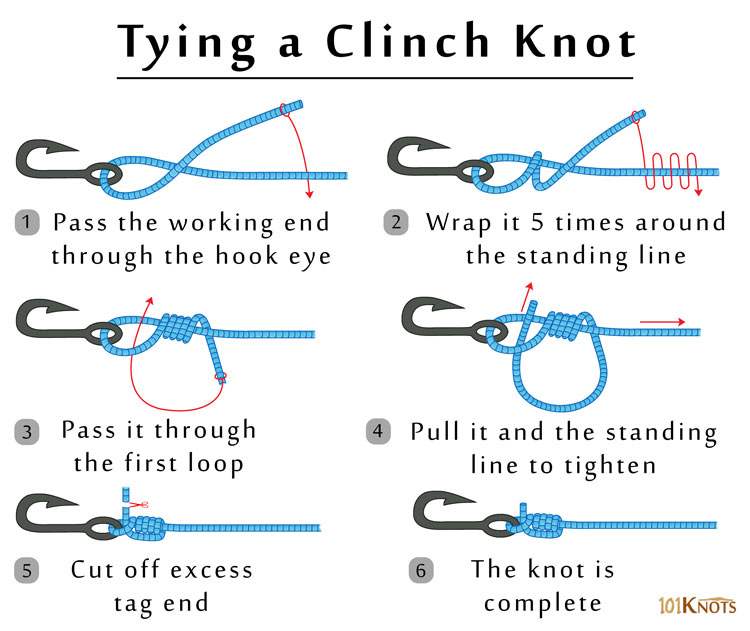

He slid the line through the eye of the hook, then doubled it back so he could hold both ends between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand. Mr. HB looked at me and said, “Seven times, no more – no less.”

He turned the hook seven full rotations, poked the end of the line through the small gap just above the hook eye, then pushed the line through the loop he had just created. Then he said, “Before you cinch the knot, moisten it.”

He wet the loopy tangle with his tongue, then gently pulled on the hook.

The knot tightened around itself until there was a tidy stack of coils gathered just above the eye of the hook. He held the knot in a beam of sun coming through the small kitchen window and said, “Not a single kink in the line … that my boy is a properly tied improved clinch knot. If you never learn any fishing knot other than this one, you’ll probably be okay.”

He took a sip of coffee and said, “The most carefully tied fly attached to the most expensive line are useless if they aren’t joined by a decent knot.”

I still wasn’t sure if he was speaking to me – I wasn’t even sure if he knew he was talking out loud. Either way, what he said seemed to make sense.

“Thank you, Mr. HB,” I wheezed into the smoky air.

My granddad, Baker, sat at the head of the kitchen table blowing smoke rings and making a point to only partially pay attention. As he crushed a butt in the ash tray, he quipped, “Seems like a lot of fuss just to catch a fish. I’ve caught plenty on a sapling with cheap line and an overhand knot.”

With a smirk only I saw, Mr. HB replied, “I bet you’ve lost plenty too. I’ve never lost a fish that could be blamed on this knot.” He added a wink in case my young sense of humor failed to recognize the smirk and provocative retort.

Granddad processed what he’d heard as he lit another cigarette, then blurted, “Oh for God sake’s HB, you’re so full of crap I need boots just to talk to you.” He didn’t really say crap.

Mr. HB looked back to me, now with an ear-to-ear grin, and said, “I’m not sayin’ you won’t lose another fish. I’m just sayin’ that if you do, it won’t be the knot’s fault.”

The grin faded as he gazed at the knot still lit by a beam of sun. “Yeah,” he continued, most certainly talking to himself this time, “it’s the tie that binds.”

Granddad just huffed, though it was a huff of begrudged agreement.

I knew enough to know they had just seen eye-to-eye on something, though I had no idea what that something was. But at the time it was of little importance compared to learning my first honest-to-goodness fishing knot. I figured I had a few more steps to take before I could call myself a fisherman, but no matter how many steps there were – or where they would take me – I had that fishing knot thing covered.

Later that evening I sat on the front porch carefully tying a number 2 hook to the 8-pound test of my Zebco rig while Granddad once again blew smoke rings, this time from a creaky old rocker. I would tie the knot and then cut through the middle of it with my toenail clippers just so I could tie it again.

From over the rail I heard a passerby say, “Nice knot son. Clinch knot ifI’m not mistaken. I prefer the Pitzen knot myself. But it’s certainly better than the overhand your granddaddy uses.”

“Humph, shut up Charlie,” was Granddad’s reply.

As if he hadn’t heard, Mr. Prince continued, “Son, you keep practicing that knot. And if you want to learn a Pitzen, you just come down and see me. Remember, if you tie enough of those knots, you’ll wake up one morning and realize you’ve tied yourself to a lot more than hooks.”

When Mr. Prince had moved on down Main Street my granddad asked, “You sure you want to be a fisherman boy? They seem like a bunch of smart asses to me.”

“I just wanna catch fish, Granddad,” was my bashful reply.

I was about to ask him what the heck I was missing about knot tying when he announced, “Let’s go fishing.”

He left his creaky rocker and zipped through the even more creaky screen door and emerged a minute later with a sandwich bag full of chicken livers. “Let’s go put those new knots of yours to work.”

We walked to the end of Main Street, before turning left onto the steep, one-lane road that led to a boat dock on the Potomac. Once on the bank of the river, Granddad settled onto an exposed maple tree root while I tied a liver to my hook and attached a couple split-shots to my line.

I laid the rod in a forked stick that had been stuck in the river mud, then settled onto a root near Granddad. He blew smoke rings that drifted into the maple branches, while I watched and wondered if there are other knots I’d not heard about.

The infinite calm of my granddad combined with the hypnotic sway of the branches over the lazy roll of the Potomac was more than I could bear, and as my chin began to dip to my chest the bell on the tip of my rod jingled. I snapped to attention but wasn’t sure if the bell had actually sounded – it could have just been Granddad messing with me with the change in his pocket.

But the bell jingled again, and the rod bent toward a Potomac catfish. I grabbed the rod, set the hook like the guys on TV, then fussed with the drag like I knew what I was doing.

Granddad offered his thoughts in the form of, “For God sake’s boy, wind him in!”

I raised the rod tip and pulled against the heavy cat. The rod jumped and bounced as the fish struggled to break free. My young hands and knees trembled with excitement. The catfish swam downstream, peeling line from my drag through open water. I held firm against the pull and enjoyed the fight.

Then he turned upstream, which put a little slack in the line. I reeled quickly as I could to gain pressure as he swam by and headed toward a big sycamore that had been pushed into the river by a summer storm.

I tightened the drag as much as I dared, but still he stripped line. I pulled with all the strength I could muster, but despite my best effort and a prayer, the cat made it to the sycamore and the branches below the water’s surface.

“Just give a slow steady pool,” Granddad said gently. “He’ll come out … or he won’t.” He always had a way of cutting to the chase.

I knew he was right, so I pulled and pinched the line against the rod so it couldn’t slip and pointed the tip at the fish so the rod wouldn’t weaken my pull. At first it felt like the fish might pull free. A moment later the line snapped.

Normally, it would have been no big deal- the rocky bottom of the Potomac was strewn with logs so I was used to losing fish. But this time I knew what was coming.

“Wonder if the knot held?” I didn’t even have the line back on the reel, and Granddad asked the question we were both wondering.

“Guess we’ll never know, will we, Granddad?” I knew there was an edge to my response, but he could have at least waited a couple minutes before rubbing it in.

“On second thought, I bet the knot held. A knot tied by as big a smartass as you surely did,” he quipped as smoked leaked from his mouth and nose.

“Sorry, Granddad.” I knew better than to cross the line too far.

Then we saw it. A branch on the fallen tree splashed. We both stared in silence wondering… Then it happened again, this time two pulls and two splashes.

“Well I’ll be a…I think your fish is still caught,” Granddad said, with not near the amazement there would have been had I said it first.

I placed the rod back into the forked stick and waded toward the twitching branch. In waist-deep water I wound the line around my hand a couple times and used my Uncle Henry pocketknife to cut the tangle. I walked quickly to shore, dragging the worn-out catfish behind me.

I pulled the line hand over hand until I could see the fish. Then with both hands on the line I gave a steady heave-11O, landing the catfish on the bank without so much as a flop. I removed the hook and admired the sleek channel cat. Once I was sure that I’d looked at him long enough to never forget, I began to lower him back into the river.

“What are you doing, boy?” Granddad exclaimed.

“We can’t keep him now, Granddad, not after all that,” I said, unwilling to make eye contact.

“I suppose you’re right … let him go then.”

I could tell he didn’t like the idea of letting a beer battered supper get away from him – but I also knew he didn’t have the heart to make me keep him.

As the fish swam back to the murky depths of the Potomac, Granddad said, “Why don’t you show me how to tie that knot that held up so good.”

I looked at him, saw the expression on his face, and immediately understood what Mr. HB and Mr. Prince had been talking about.

Three decades after landing that fish, the improved clinch is the only knot I can tie without removing the cheat sheet from my fishing vest, and long ago I resigned myself to the fact that I will never be a fisherman.

Don’t misunderstand; I genuinely enjoy the pursuit of fish. But the simple truth is that maybe five percent of the people who wield a rod and reel will ever really be fishermen. The rest of us are just well-intentioned people who fish with varying degrees of competence and success, and who call ourselves fisherman in the same way we call the items on McDonald’s menu “food.”

I have learned through a lifetime of drowning worms that a fishing knot does infinitely more than bind a fly or lure or bait to a line, it binds a person to the idea of catching a fish. Once a person is bound to that, they are bound to an endeavor that will bring a lifetime of happiness and misery and meaning.

Fishing knots have bound me to the purple and red clouds of sunrise that reach to the horizon, making it difficult to tell where water ends and heaven begins. They have bound me to rivers and streams, the delicate lifeblood of nature, and to the responsibility of preserving them. I’m bound to the sound of surf and the smell of salt. I’m bound to the perfect roll cast – an endeavor as purposeless as finding the edge of the earth. I’m bound to the moment when I lift a fish from the water, and then release it to be free – or slip it into my creel.

Most importantly I’m bound to the responsibility of passing the heritage of fishing to my children and to the pleasure of teaching them the skills that every child should know. Most especially, I’m bound to the look on their faces when their bobbers dip below the water’s surface.

A long time ago I learned how to properly bind a hook to line. At the time I had no idea that I would bind myself to so much by simply tying knots. If asked today how I feel about that, I’d just huff in agreement, and with infinite satisfaction.

From proverbs to professional tips to general words of insight, this collection of angling wisdom is the go-to guide for anyone who loves some aspect of the wonderful world of fishing. Buy Now

From proverbs to professional tips to general words of insight, this collection of angling wisdom is the go-to guide for anyone who loves some aspect of the wonderful world of fishing. Buy Now