Growing up in the Smokies of North Carolina it was my privilege to know a number of interesting and unusual characters. Al Dorsey had to be the strangest of them all. His offbeat personality and bizarre lifestyle held great allure for boys. Frequent admonitions from my parents to the effect “you don’t need to be hanging around that dirty old man,” together with their refusal to explain why they felt that way, merely added to his mystique. An old river rat who was pretty much a stranger to soap and water, I just assumed that to my parents he was a local incarnation of some of the more unsavory of Mark Twain’s Mississippi River characters. Little did I know just how sordid a background he had or how checkered old Al’s life had been.

I knew him mostly through fishing. Every year when summer rolls around and when a string of miserably hot, humid days make for sweltering in midday misery, my thoughts wander back to yester-youth and the simple joys of catfishing with old Al. I had a whole bunch of “holes” in the Tuckaseigee River where I matched wits with Mr. Whiskers, although none of them were more than a mile upstream or down from Bryson City’s Everett Street Bridge. On the north side of the river underneath the bridge was where old Al kept his home-made, flat-bottomed boat chained to a tree. He maneuvered the boat with a long pole rather than a paddle, and his stretch of river was a relatively short one, less than a mile in length, circumscribed by rapids at either end.

As I write these words I am looking at the front page of the Bryson City Times for November 6, 1925. The lead news for that week focused on Dorsey, revealing an aspect of his life unknown to me until long after I reached adulthood. The headline reads: “Al Dorsey, Slayer of Muse, Gets Sentence of Ten Years. Was Tried for Second Degree Murder.” The subhead, in an interesting bit of editorializing mixed in with news, states “Sentence Regarded as Extremely Light.” When I first read this account, realization finally dawned why my parents frequently suggested it would be best to avoid Al’s company, never mind that Dad did acknowledge Dorsey was masterful when it came to catching catfish.

My thinking, throughout boyhood and well beyond, had been that they discouraged any connection with old Al simply because he always looked unkempt; drank more than a bit; in the summertime wore a visible layer of grime on his ankles and lower legs instead of socks; and dressed in a somewhat unusual fashion for hot weather with overalls, long johns, a long-sleeved shirt, and brogans. When one was downwind of Al the air tended to be pungent indeed. Yet I found him endlessly fascinating. He was kind to apprentice river rats, kept a watchful eye on our youthful shenanigans, and readily shared his matchless knowledge of the fine art of catching catfish.

Dorsey was found guilty of second degree murder (it was a crime of passion—the man he shot had been fooling around with Al’s wife) and sentenced to “not over ten nor under eight years at hard labor in the state penitentiary.” Apparently his time of actual imprisonment was appreciably shorter, because the 1930 census shows him back living in Bryson City.

My acquaintance with the man came long afterwards, and as a boy all I knew, from the time I was 10 or 11 well into my teens, was that being around old Al was pure pleasure. Throughout the summer he fished, day and night, in the waters of the Tuckaseigee. During the day he ran trot lines and throw lines, did a lot of pole watching on the bank, and also made his way up and down the river in his john boat. At night he fished from the bridge.

To a starry-eyed boy enchanted by anything connected with hunting or fishing, his knowledge of the river had a mysterious, almost magical quality about it. Disreputable though his past may have been, he always had time for boys like me who spent a lot of time fishing and piddling around at the river. Similarly, he willingly, even eagerly shared his knowledge of how to catch catfish, something at which he was a true master.

Everyone in the small town knew him, and at some point during my close acquaintance with Al he accomplished something which was the talk of local barber shops and the gang at Loafer’s Glory (a local outdoor gathering spot for telling of tales) for weeks. One night while fishing off the Everett Street Bridge he hooked a mighty catfish on the only decent rig he owned, a steel rod-and-reel outfit equipped with nylon line. An epic battle ensued, with scores of people lining the sidewalk on the bridge as it unfolded. After the better part of a half hour Al managed to ease the fish close towards shore and then, carefully working the rod around a series of street lights which sat atop the bridge railing, he made his way down the bank at the south end of the bridge. As the catfish wallowed in the shallows Al waded into the river, ran his arm through its mouth, and wrestled it onto the bank. It weighed upwards of 50 pounds, a veritable giant for a mountain stream.

At some point, long after my halcyon days of innocent youth spent in his company, the decaying mansion in which he lived reached a point of no return. Dorsey moved to a nearby slab shack and somehow eked out a living. Then, in the final decade of his life, a simple act of charity wrought a glorious change in the man.

The recently widowed wife of a local taxi driver gave him her deceased husband’s clothes. Somehow this small token of caring and concern awakened long dormant pride in Al. According to the lady, “from then on he started dressing up even though until that point I never knew him to wear a decent pair of shoes in the summer.” It was also during this time, late in Dorsey’s life, that he began attending First Baptist Church and was converted. A photograph of Al taken during this period shows a man whose appearance is at stark contrast with the one I knew. While he is sporting a few days’ worth of whiskers, otherwise he is neat, with his hair well combed and dressed in a nifty shirt and a sport jacket.

Old Al was one of those delightful characters, and today they seem to be in increasingly short supply, who made the Smokies of my boyhood such a wonderful place to come of age. This troubled, tattered soul may not have been the finest of role models, but he was a first-rate mentor when it came to one particular type of fishing. Al Dorsey lent a degree of color to my youth which has only become more striking with the passage of time and the acquisition of additional knowledge about him. Whatever may have been his shortcomings and sins, my memories of him are filled with nothing but fondness. I will never hear Alison Krauss and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band sing the grand bluegrass classic, “Catfish John,” without thinking of “Catfish Al” and being stirred by the lyrics, “I was proud to be his friend.” The line fits, because I was (and remain) proud of being a friend to Al.

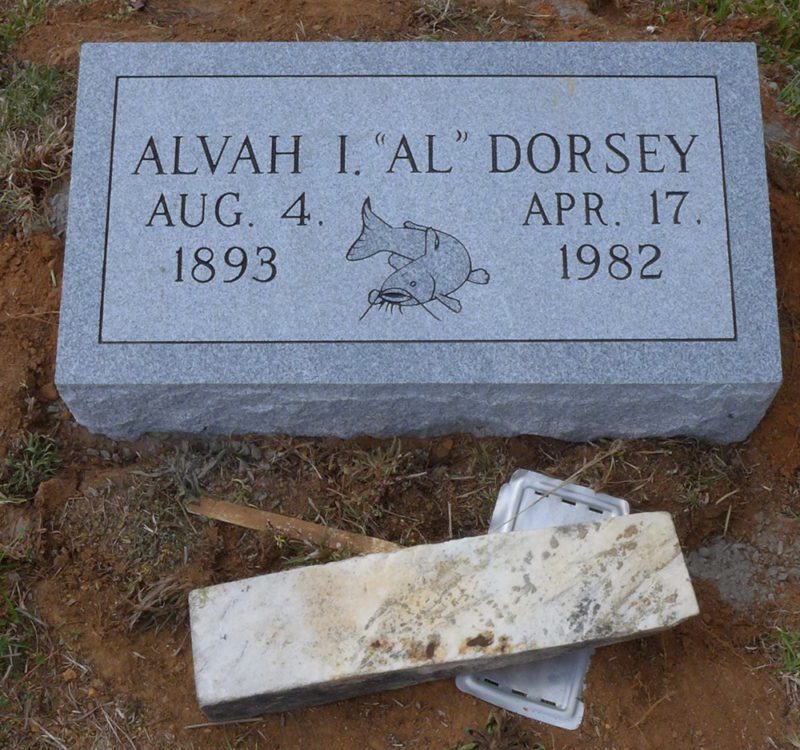

His gravesite, unmarked for decades following his death in 1982, recently received a marker. Though simple and lacking either the size or ornate nature of many tombstones in Bryson City Cemetery, the engraving of a catfish on the stone bears mute but meaningful testament to the man for whom catfishing became a metaphor for life after his release from prison.

“This piece on Al Dorsey is one of approximately 40 vignettes in Jim Casada’s book, ‘Profiles in Mountain Character.’ To learn more contact Jim at jimcasada@comporium.net.”