When their production lines weren’t manufacturing firearms, many gun companies turned to making a wide range of household items.

When’s the last time you saw a Winchester lawn mower?

Whether it’s true or not, I like to think that the concept of “branding” came about by cowboys in the 1880s slapping a scalding iron on the backside of a steer. Their outfit’s name was clearly marked, cattle rustlers with a herd marked with another man’s sign were hanged, and ownership was clear as a bell. To this day, if you want your own brand you must consult an encyclopedia-sized book that lists every registered brand, and if it’s taken you have to come up with a different option. That attention to detail means when folks see the mark they know what’s what. It makes perfect sense to me.

A Winchester motorcycle recently auctioned by James D. Julia.

Say the name Remington, Winchester, L.C. Smith, Parker Brothers, A.H. Fox, or Colt to a sportsman or woman and they’ll no doubt say, “Guns.” Why wouldn’t they? It’s the hallmark of those companies’ brand. Add a dash of romance, history, legacy, quality, and innovation and we all come running. The Winning of the West is far sexier with a Winchester ’94 and a Colt Single Action Army than with a plow.

A Parker Brothers coffee grinder.

But back then those companies were machine shops. Sure, they sold rifles, shotguns, and pistols, with some models being more popular than others. Firearms often were the lead products, high-dollar items that fetched a better retail price than curtain rods or housewares. If those firearms were designed according to manufacturing budgets, they offered the company significant amounts of net profit.

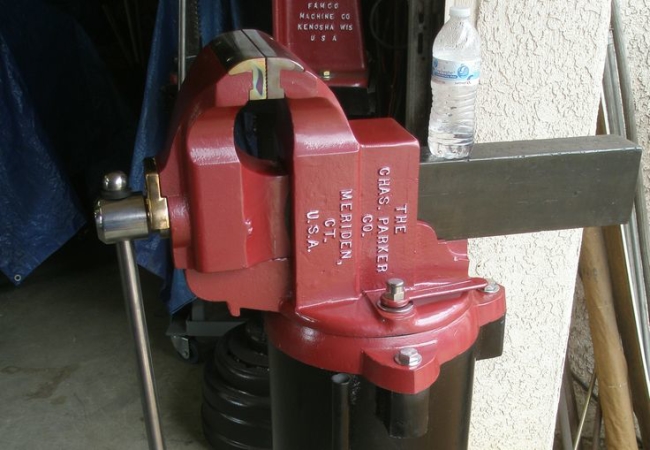

A Parker Brothers vise.

When the production lines weren’t manufacturing firearms, they produced products that were necessary, albeit mundane. Screws, door hinges, latches and knobs—anything that was made from machined metal. It’s the way the companies stayed in business, and it made perfect sense. Savvy companies still use that model today.

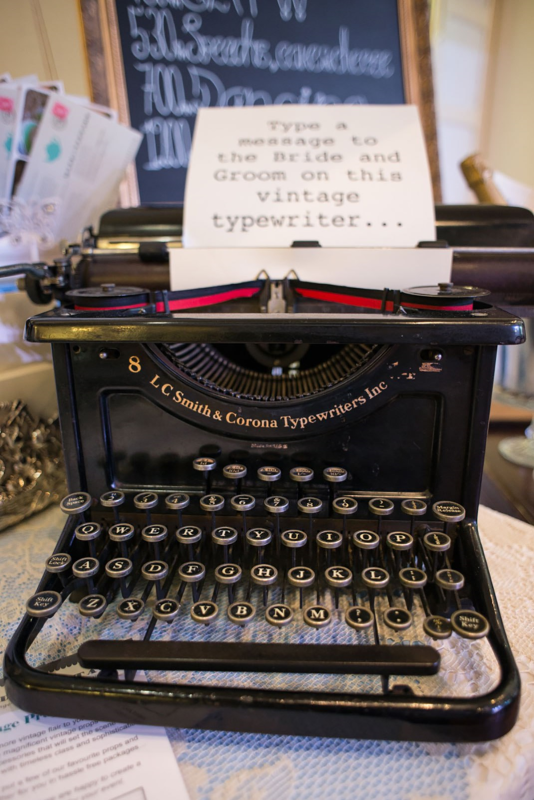

An L.C. Smith typewriter.

I got to thinking about the concept last fall. My wife, Angela, and I were in between grouse covers, and as we drove around we saw a run-down antique shop. We’re both suckers for old gear, and since we needed to cool down the dogs, we swung on in. Back in a dusty corner was a crate. It was boring, indeed, but on closer inspection it bore the Winchester name. At one time the shipping crate housed a Winchester reel lawn mower, the push kind that made kids whine when gas-powered versions came along. The box cost five bucks—what a deal—and that price made it easy to toss in the truck and bring on home. We wished we had the box’s contents, though, for that would have been worth something a whole lot more.

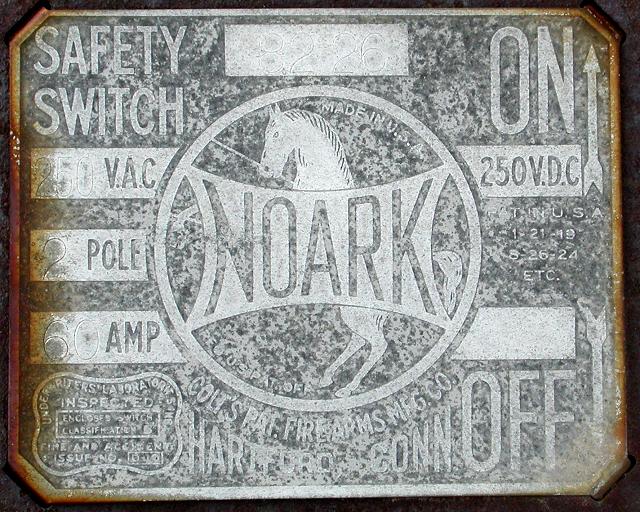

An electric switch box from Colt.

It was about that time, too, that I saw an advertisement from the James D. Julia auction house in Maine. They had received a stellar item: a Winchester motorcycle, one of only two known to exist. It was in mint condition, fire engine red, with the Winchester logo prominently displayed on the small gas tank. I chose not to attend the auction, thinking I’d walk out with a new ride that cost so much I’d have to sell my home. Auctions tend to make me to that, particularly if they offer such a unique item.

Another Colt switch box.

My friend Legh Higgins has a Parker Brothers coffee grinder in mint condition. When you think about it, what else could he use to grind beans? Legh breeds English setters from his grandfather’s stock (www.twomblysetters.com), and most folks know his grandfather Earl Twombly. Earl supplied Corey Ford with what became two of the most famous English setters of all time, Cider and Tober (the call name being short for October). Legh carries on the family tradition, right down to shooting a Parker VH 0 frame 16 gauge, the classically traditional grouse gun. It makes sense that he shoots it after grinding beans with his other Parker.

An A.H. Fox level-wind fishing reel.

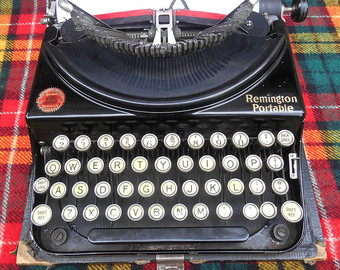

Typewriters were commonly made by many gun companies, with Remington and Smith Corona leading the charge. Finding an early model that features the L.C. Smith logo is a joy. A common joke among outdoor writers who still hunt and peck (pun intended) on the glass keys is this: “Is your typewriter choked with full, modified, or improved cylinder?” Add an Elsie typewriter to your Remington Adding Machine and you’ve got as fine a double barrel of office equipment as it gets.

A Remington adding machine.

Colt made electric switch boxes and plates. And here’s the beauty: If you bent the edges while installing them and needed to straighten them out, what better tool to use than a Parker Brothers vise? Interestingly enough, the two products were made a few dozen miles away from each other and are highly prized by collectors.

Another Remington typewriter.

When it’s all said and done and the mundane work is complete, it’s time for a sportsman to head out for a day on the water. An A.H. Fox bakelite level-wind reel is just the ticket. While surf casting for bass you can dream of pulling out your shotgun during bird season. In the fall you can catch bass in the morning and hunt birds in the afternoon, all with products made by the same Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, company. Now that adds new meaning to the City of Brotherly Love.

If you’re an addict like me, you might pass on the next shotgun, rifle, or pistol in favor of products made by those fine American companies. When the seasons are closed you can get as much enjoyment picking away at a keyboard, sawing a board, or grinding beans for a pot of coffee. For a sportsman or woman, what could be better than that?

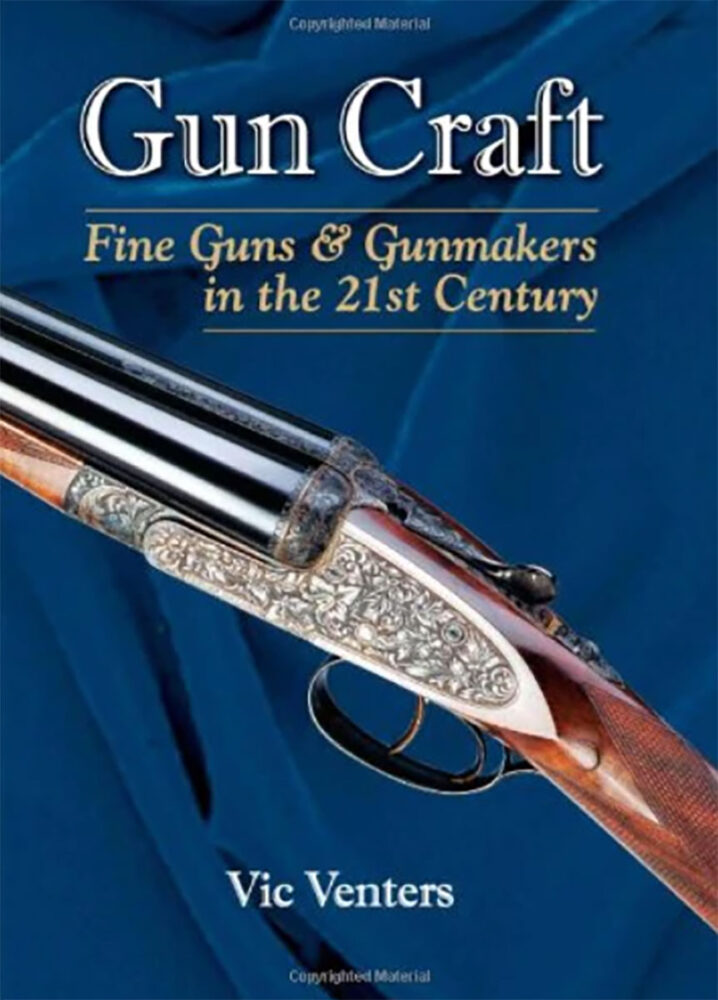

Gun Craft examines today’s artisanally made guns, as well as the craftsmen who make them. In it, the author takes the reader into the workshops and factories of the world’s best gunmakers, making their sometimes-arcane craft skills accessible and relevant to anyone who shoots, owns or collects fine guns. Each chapter explores a separate topic; each has been chosen, however, to provide readers with a unified insight into the complicated task of making hand-made guns in both Europe and the United States. Buy Now

Gun Craft examines today’s artisanally made guns, as well as the craftsmen who make them. In it, the author takes the reader into the workshops and factories of the world’s best gunmakers, making their sometimes-arcane craft skills accessible and relevant to anyone who shoots, owns or collects fine guns. Each chapter explores a separate topic; each has been chosen, however, to provide readers with a unified insight into the complicated task of making hand-made guns in both Europe and the United States. Buy Now