Two centuries. Not a bad run for any business. But all good things must come to an end – including America’s oldest firearms manufacturer.

Okay, perhaps not the end, but filing for Chapter 11 is a sure sign of tough times.

It was 1816 when Eliphalet Remington started making weapons in Ilion, New York. Yes, that’s impressive. But in Val Trompia, Italy, Beretta had already been in the firearms business for nearly 300 years! That makes them the oldest active firearms company in the world! But I digress.

Every American hunter knows the name Remington, and most have owned at least one. A lot of us still do. I bought my first Remington 700 30.06 in 1972. $136, give or take a few dollars. After 20 years of use and abuse, Kenny Jarrett offered to turn it into one of his Beanfield Rifles. The vintage 700 actions were his favorite to work with.

Today my old 700 lives on in the body of the custom-made Beanfield. Like a heart transplant of sorts. It has taken many deer along with a number of other North American ungulates.

Back in 2007, I traveled to Africa with a loaner from Remington – a 700 Custom in H&H .375. It was wicked on cape buff and kudu, yet fairly gentle on my shoulder. And it was a beautiful thing to behold. I would’ve loved to have kept it but it wasn’t in my budget at the time. So, I kissed it goodbye and returned it to Linda Powell and company.

The other Remington was and still is my Model 870 in 12-gauge. It too was purchased sometime in the 70s, but I don’t recall the price. But not much. Armed with a few Rem-Chokes and a mix of 2 ¾-inch shells, I could hunt about anything on the continent shy of a grizzly. My wood-stocked pump and I killed white-tailed deer, hogs, turkeys, squirrels, rabbits, ducks, doves, woodcocks and marsh hens.

I still have that 870, and it continues to accomplish everything it did 40 years ago. It’s the shooter who’s lost a step or two.

I bought my both my sons 870 20-gauge guns in the early 90s. They tended to jam easier than mine. I noticed the little end cap on the spring was now plastic rather than metal. A small change, but it definitely had a negative impact on performance. But still, it was a Remington, and almost as perfect as my 70s model.

I recently joined a couple of friends in North Carolina for some duck hunting. They carried really nice semi-automatic shotguns, with matte black synthetic stocks, shooting 3 ½-inch magnum shells. Still, I held my own with the old 870. Knocked down a pair with two shots. Reloaded and took two shots to get the next bird.

Three for four. I’ll take that any morning. And should I fumble and drop my gun in the drink, I can get over it, at least financially. Although I’d likely shed a tear or two for the memories we shared.

I hope I don’t have to get misty-eyed over the sinking of such a grand old American company as Remington. There’s still a pulse. There’s still hope. Hold steady, Big Green. Hold steady.

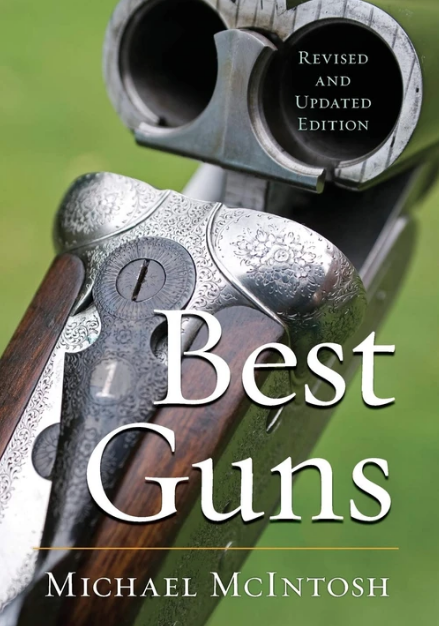

This is Michael McIntosh’s classic book on fine shotguns, in a fully revised and expanded form–covering gunmakers who have become prominent since the first edition was published in 1989 and McIntosh’s continued research into the nature of the shotgun and the people who make them.

McIntosh divides his nearly encyclopedic gathering of gun knowledge into two distinct sections. The first is devoted to the best shotguns ever made in America, “American Best,” looks at each of the finest guns made in the United States during the Golden Age of gunmaking. Names from the past such as Parker, A. H. Fox, L. C. Smith, Ithaca, Lefever, and others are treated in greater detail, including newly manufactured American classics that bear those same names.

In the second section, McIntosh explores the revivified world of gunmaking abroad–in England, Spain, Italy, and elsewhere, places where traditional craftsmanship and modern technology have combined to make the turn of the twenty-first century the most vibrant and exciting period in fine gunmaking in nearly a hundred years. Buy Now