“Warren Caballas gave me this rifle back in ’31,” Pappy said. “He was this high-class Puerto Rican, and I paneled his gun room in pecky cypress.”

Pecky cypress has holes all through the wood, big as your little finger. Looks good from a distance, up close the holes are filled with spiders and dust. That would be Alligator Hall on Coosaw Plantation, a beer and dance joint back in the phosphate rock boom, burned once, twice, rebuilt as a home. And it was Juan Caballas not Warren, but I knew better than interrupt one of Pappy’s tales. His days were short, and I wanted all the stories to come out before I could not hear them anymore.

Krag Jorgenson rifle, U.S. Model of 1892.

Pappy was in a wing chair by the fireplace, Colonial bricks he had laid himself, in a house he had built himself, before a window he had set himself, looking out upon the river he was raised upon, lived upon and too soon got old upon.

The rifle was a Krag-Jorgenson carbine, U.S. Model of 1892, Springfield Armory, like the one Teddy Roosevelt carried up San Juan Hill. Pappy’s hands were spotted with age, his fingers gnarled but still strong. He worked a lifetime with wood, houses, docks, seawalls, furniture at the end. If it was wood, it was good. He ran his hands down the walnut, cupped the bolt handle but did not work the action.

“When I got through with his gun room,” Pappy said, “he told me to pick any gun off his rack. I chose this Krag. He said he took it to Africa, shot a lion with it.”

There was a Lyman peep sight with a flip aperture, a fine hole for long shots at impala, an open one for up close and dangerous, which is how lions are hunted.

The .30 Caliber U.S. Government, as it was known in those days, the .30-40 today, was akin to the .308, but with a long, round-nosed 220-grain noodle of a bullet, a load a .308 could never handle. The action was as slick as goose grease. Just open the hatch on the right-hand side and shovel in the shells. So long as they were pointed the right direction, so long as you do not insert a mini-bottle, your cigarette lighter or your last girl-friend’s lipstick, no Krag ever jammed—ever—an admirable asset with lions.

But the Krag fell out of official favor after San Juan, where the Spanish Mausers gave Roosevelt’s men such a serious mauling, though it remained a favorite in the gamefields, one giant step above the .30-30, ideal for deer, bear and moose in the Northeast woods and in Africa, as Juan Caballas’ Krag would testify if it could speak. It would kill a lion dead as hell with a cool head behind the gun, a steady finger at the trigger and the right bullet in the right place.

The love of Jesus might help.

But you can’t do that anymore.

Hemingway shot a lion or two with a Springfield .30-’06 but now the PH’s, the professional hunters, have wearied of “The Night of the Living Dead,” the blood-spoor in fading light, the thing most likely to get them killed, outside of malaria, sundry social inconveniences, Marxist insurgents and ivory poachers, life in the bush being wonderful but sometimes short. So most places you must shoot a .375 Holland and Holland Express or something equally robust at anything that’s inclined to gnaw or trample.

“Pappy, I got a notion to go to Africa. Not this year but maybe the next. Maybe I could bum this Krag and take it back?”

He smiled that little possum grin he was famous for. “You won’t shoot a lion, will you?”

“No sir, I won’t.”

“I couldn’t think of you killing a lion.”

“I promise I won’t.”

“Well, let me think about it. You know your brother has an interest in this rifle; Jack does too.”

Jack, the brother-in-law.

We bade farewell. I squeezed his hand, ran mine briefly through his hair.

I never saw him or that Krag again. I was miles away the night he passed. Jack got there between the death and the funeral. I got a Ballentine wooden scotch box dated 1944 that rattled when I shook it. After appropriate grieving, I took a pinch bar to the lid.

Rusty pipe-fittings.

But that’s OK. I went to Africa with a 7×57 Mauser, the same rifle that gave Teddy Roosevelt such ever-living hell. I took a several antelope, a warthog and came damn close to popping a lioness that was fixing to swat me right out of the Land Rover, but I did not, one lion step and three seconds from violating my oath to Pappy.

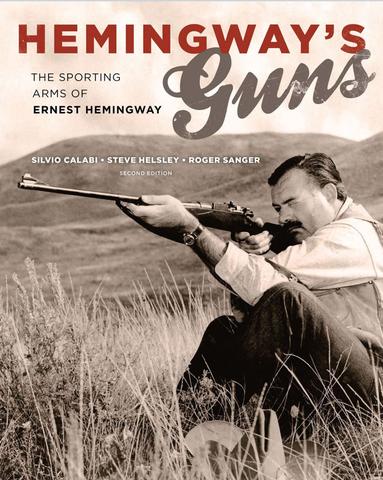

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Shop Now

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Shop Now