A black duck hunt in a tiny pond in the woods will long remain in memory. There were two of us, a guide and a Chesapeake retriever.

When we got to the pond there were a couple of wood ducks there and about half a dozen blacks. They promptly got out.

The guide put out the stool and we settled down to await events. It was a bright day with a lively southwest wind blowing, just right for the ducks to drop in through a good lead at the northeast.

After about an hour the first one came, high, into the lead, wings set and tearing down fast. We had settled who should take the first single, and that man took him very neatly as the duck changed his mind and started out as fast as he came in.

A half-hour brought a pair swishing down in the same high-speed fashion. They both stayed with us, and the dog, sensing the quality of the day and the shooting, did his proud part by bringing in both ducks by the necks at the same time. The ducks continued to come, sparingly but just right, until we had 15 down without a single miss.

Th 16th duck ruined us. We had planned to quit early so we could get in some flounder fishing, but we did want that last duck and that perfect score.

This black duck was the first and last that I have seen rattled. When we got up to take our deliberate turns at him, he flew right in our faces and went away over our heads through the barrage without losing a feather.

Or maybe he wasn’t rattled at all, but had taken a lesson from some of the grouse that lived in the surrounding woods. You know how a grouse in a tight corner will ruin you by flying straight in your face. Maybe that black duck was the smartest of all that smart race.

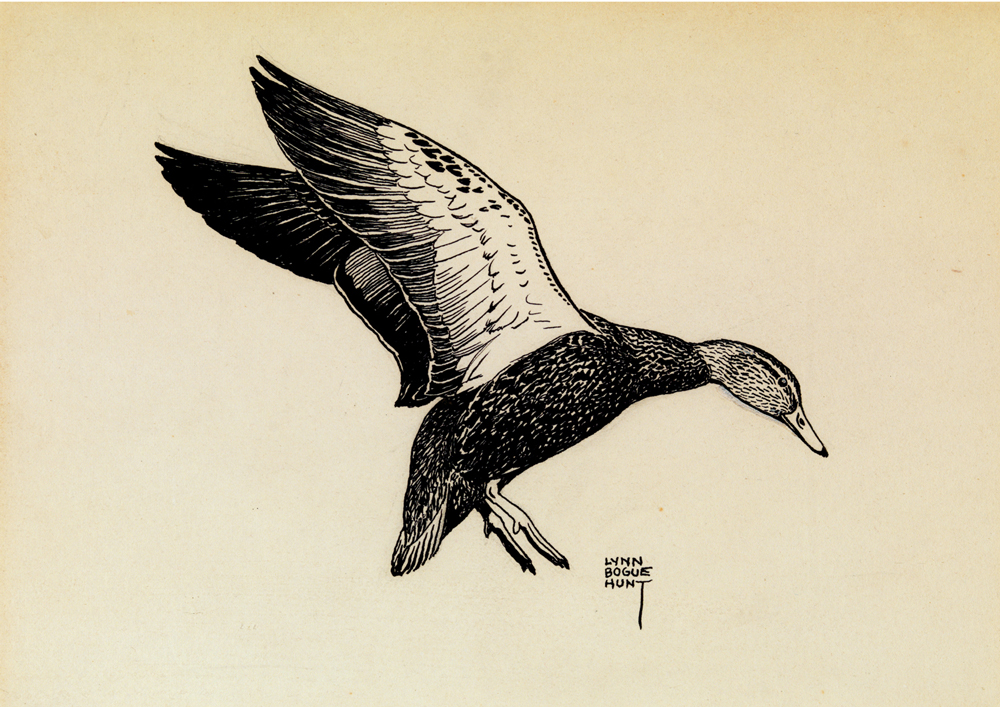

“Black Duck,” ink on board by LBH, circa 1930.

Another memorable day with black ducks came about like this: We had a freeze the night before and we waited for the sun to get fairly high, so we didn’t get to the pond until about ten o’clock. The pond was frozen except at one end where a spring kept a 50-foot patch of water free of ice. There were at least a hundred blacks in that open water and no one knows how many green-winged teal. Anyway, they were whacking each other’s wings as they swarmed.

“They will be drifting back in about an hour,” said the guide.

They didn’t drift back in an hour, nor in an hour and a half. So we sent the guide to see if the ducks were using the tidal river where it had not frozen. By the time he got back the temperature was colder and our pond had closed up almost completely, so we went to a blind on the stream. We got a few shots there. Around 2:30 the wind came southwest and the air warmed considerably.

“Maybe,” said the guide, “by now the spring in the pond has opened up a bit. It can’t be much slower shooting than here anyway.”

“Black Ducks at Dawn,” oil on canvas by LBH, circa 1935.

So we went back to the pond, which was now half open water, but no ducks were there.

We waited and we waited and we waited. The pond was now completely clear of ice, but on this late December day the light in the woods was draining away, when, suddenly, six blacks slammed into the pond from nowhere. We got three of them. By the time the dog had them in, more came in small bunches until we began to worry about the number we had down. They came so fast we had lost all count.

The legal hour was close at hand when we quit, but the ducks were still pouring in. They swooped over the guide as he was picking up, and when we got to the car black ducks were still spinning overhead for that pond.