Were you to dream a moose hunt, this classic north country wilderness would be the perfect place.

It was the quintessential north woods moose hunt for five days. Wild, serene, beautiful and perfect for the huntress. But then it was the moose’s turn. One tends to overlook the perspective of the prey in these adventures. Understandable. The bull my wife, Betsy, sought probably wasn’t considering her point of view either. His defenses were primed against our best offense by distant memories of predators past, of grizzlies huffing and roaring through the aspen groves, of wolf packs slavering at his heels. We surely weren’t the first humans he’d evaded, either, deceptively calling like the lusty cows he sought each fall, fooling him until a subtle shift in air currents drifted an olfactory alarm his way.

Chase Gallagher with his grandmother, JoAnne Potter, who keeps the fires burning at their wilderness hunting camp in Alberta.

This 2017 hunt had begun long before that calendar year rolled around. It had started for our guide and outfitter, Chase Gallagher, in the 1990s when, as a child, he visited his grandparents’ trapline, got bitten by the hunting bug and contracted incurable hunting fever. Like his grandfather, like his grandmother, Chase took to the woods, rivers, lakes and meadows of this Chinchaga River valley, lured by moose, caribou, bears, wolves, otters and beavers, enthralled by flowing rivers rippling with trout, enchanted by sparkling lakes lapping sedge and willow shores.

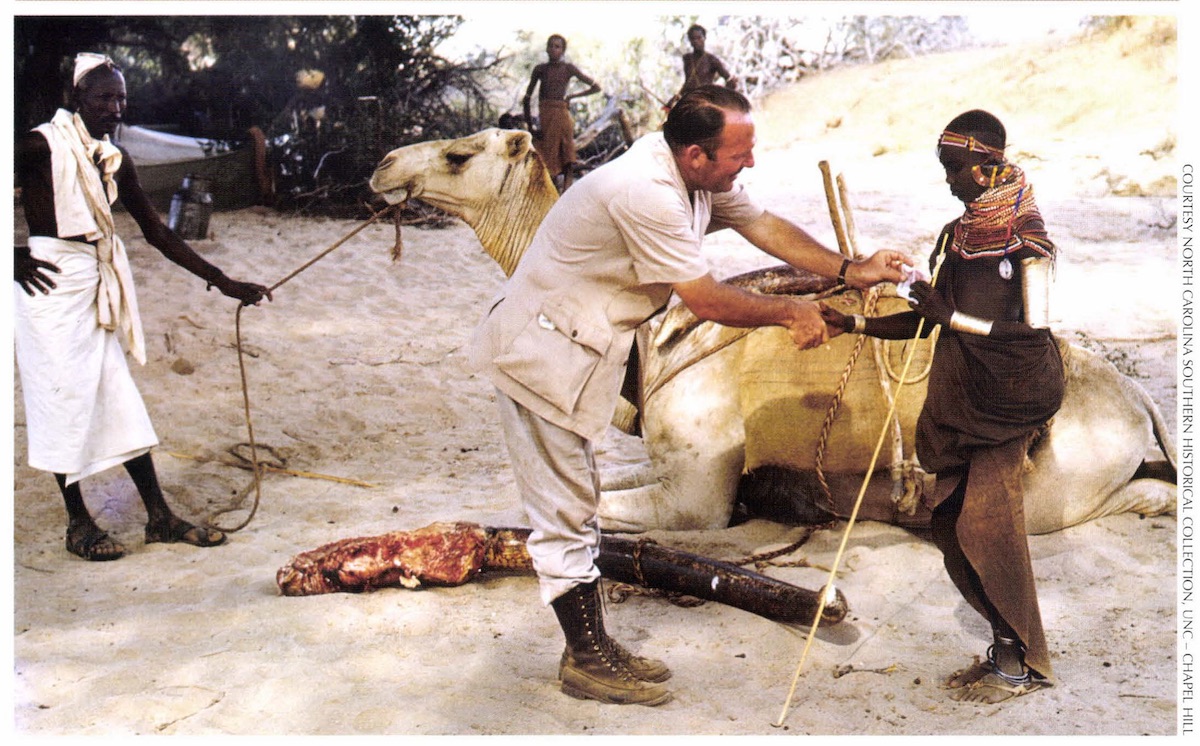

For Betsy, this moose hunt started in Africa soon after she brought her first animal to ground. A perfectly executed stalk. A perfect shot and a ram springbuck—the most delectable venison in Namibia —was hers. She took pride in sharing it with the tracker whose African woodsmanship had inspired her to take up the stalk. Suddenly, she understood what pulled her husband to the wilds year after year. She’d touched the ancient hunter-gatherer heritage that defines the human species.

“Now I want to hunt a moose,” she declared. Fifteen years later she finally got the chance.

Were you to dream a moose hunt—a classic search for a dark, long-legged, big snouted, heavily antlered, massively palmated deer—you might conjure a north country lake smooth as glass mirroring a phalanx of white poplars. One or two should still be shaggy with leaves gone gold. Throw in copses of dark green spruce for contrast. Buffer this lakeshore with a broad rim of pale yellow cattails interrupted here and there with bulging beaver lodges. Animate this with beavers carving silver Vs on the glassy surface.

Enliven this scene further with a line of big, white swans passing overhead, tooting languidly against the blue sky while ravens cronk and practice aerobatics above the trees. Far out on the lake could be a splashing, diving, feeding flock of bluebills fattening for their upcoming flight to that November lake you hunt in northern Minnesota.

Now introduce yourself into this dreamscape. You’ll be cleaving the mirrored water in a green canoe, your guide pulling steadily from the stern. Feel the liquid swirl round your paddle. Hear the rhythmic gurgle and drip off the blades. Glide to a stop as your guide cups hands to mouth to moan and whine like a cow moose. Listen, head cocked, mouth open for a distant grunt. And hear instead a solid whack, clunk, crack. Bone on bone, heavy palms slapping. Tree limbs snapping and cracking. There is a bull battle royal underway on the north shore a quarter-mile away. Plunge in your paddle and pull hard for those last 400 yards toward the culmination of your dream.

That is how it happened for my wife last fall in that lovely chunk of wild Alberta drained by the Chinchaga River. Here, young Chase Gallagher has taken up where his grandparents left off, hunting and guiding from the hand-built log cabins they’d built 30 years ago.

Betsy waits in a dense copse of poplars for a bull to respond to Chase’s call.

From the early 1980s until the mid-1990s, Dennis and JoAnne Potter ran traplines and lived old school in this wilderness of rivers, lakes, beaver ponds, bogs and forests, stretching and curing lush furs of beavers, muskrats, mink, martens, wolves, wolverines, fox and lynx. They ran their lines by day, skinned their catch by night, cut trails and built cabins as time allowed. In the off season—early fall—they guided moose and bear hunters, padding their income and expanding their experiences.

Alas, the Potter’s sold their trapline to another outfitter before Chase was old enough to work for them. Instead, he guided for other outfitters in the far northwest, advancing his own woodsmanship. He tracked, glassed, stalked and called game. He intercepted browsing caribou and swaggering grizzlies. He quartered moose and packed horses, set up camps, skinned and fleshed. When the outfitter on his grandparents’ old territory was ready to sell, Chase was ready to buy. And grandma JoAnne was right there to help.

“Chase is an excellent guide,” she told me as I nursed a coffee in the main cabin she and her late husband had built. “But guiding hunters and managing an entire camp aren’t the same thing. I know this place and how it runs better than probably anyone, so I thought it would be fun to help out this first year.”

Jessica Hall and Chase with the bull she dropped with one shot from her Savage .308.

Help indeed. At 77 years young, JoAnne could and does outwork men half her age. She startled us at the trailhead at midnight, driving up confidently in an Argo. Believe me, a 77-year-old grandmother man-handling an ATV out of a rutted trail in the black wilderness is not what you expect to meet after a three-hour drive under the northern lights.

“Throw your gear in the trailer,” she directed. “The cabin’s only a half-hour away.”

And off we went, churning through potholes, bumping over fallen limbs, imagining wolves and bears watching from the big woods as we savored this leg of the adventure Betsy had begun 15 years earlier on the sandy edge of the Kalahari.

For the next week, while Chase concentrated on the hunting, JoAnne kept the home fires burning. She stocked firewood, cooked breakfasts and dinners, packed lunches, cleaned cabins and chased black bears—and surely some old memories—out of camp. And whenever a hunter was within earshot, she entertained with incredible tales from the trapline. Grizzlies tearing through the roof. Blizzards obliterating the trail. Snow machines plunging through the ice. Floods sweeping away hand-built bridges. Traps freezing up at minus-40-degrees. Wolverines eating martens and lynx from the traps.

“It was an adventure,” she admitted. “A hard, wonderful adventure.”

But that was then and this was now. Chase wasn’t just trying to find a bull moose for each of two hunters, he was trying to get each of two relatively inexperienced female hunters a bull moose.

Betsy Spomer scopes the dense forest along the Chinchaga River for any sign of a bull moose. In First Nations, Chinchaga means “Big Wood River.”

I had wolf and black bear tags and a slick handling, sweet shooting Kimber Subalpine bolt-action in the increasingly popular .280 Ackley Improved (a modified .280 cartridge which is itself a modified .30-’06), but I would use it only after Betsy got her moose.

The other hunter, Jessica Hall, a hairdresser, had driven herself hundreds of miles to indulge her dream hunt for a bull moose, and it came true on our third day.

Chase had motored the three of us down his grandfather’s old trapline trail—an increasingly overgrown crisscross of seismic lines cut through the forests and bogs by oil prospectors in the 1970s. We disembarked from the Argo to work a lakeshore and soon heard a cow moose moaning.

Betsy and I tiptoed along the shore while Chase led Jessica back up the trail to cover the backdoor. When they turned the corner at a junction, the cow and calf trotted out of the willows.

“Get ready!” Chase hissed. Jessica did, raising her Savage 308 Winchester just as the bull stepped into the clear. Chase stopped him with a grunt and Jessica truly stopped him with a precise shot to the heart. One down.

Betsy’s chance came harder. Each dawn would find us perched above a beaver pond, watching and hoping a moose would wade in.

Chase and Betsy set off down the lake in search of a bull. On this outing, they saw beavers, otters, swans and ducks, but no moose.

“I’ve seen two or three bulls at a time in here before,” Chase said. “Let’s try a different spot.”

And we’d chug down the cutline, weave through the poplar woods to the next likely pond, bog, or lake, watching for tracks and droppings, listening for moaning cows or grunting bulls.

At each location, Chase would do his own moaning and grunting, sometimes whacking logs and limbs in imitation of a rutting bull. The terrain, relatively flat, was nonetheless beautifully dressed in an ancient mix of poplar woods, spruce forest, sedge meadows, cattails sloughs, willow thickets and glacial lakes. Yellow larch trees glowed like candles as shafts of low sun beamed through scudding clouds. Lightly frosted bunchberries shined like miniature apples above beds of plush green mosses cushioning the forest floor. Crimson cranberries dripped from naked limbs like miniature Christmas bulbs. Sharp-tailed grouse flushed from the trails and ruffed grouse eyed us warily from overhead limbs. It was almost a fairytale landscape, but sharp winds and plunging temperatures kept us shivering in the real world where a wrong turn could spell disaster.

Over the long days we stumbled upon a few rubs and one massive rutting pit, but the Moon of the Rutting Bulls had waned. No moaning cows. Just one, distant, grunting bull that wouldn’t show itself.

“Pack up everything you’ll need for two or three days,” Chase advised one night. “We’re moving to Grandpa’s farthest line cabin.”

The hand-built log structure perched like a storybook cabin near a big lake. It was wearing a green canoe.

“We keep it on the roof so the bears don’t destroy it,” Chase explained as he slid it down. Toothmarks in the hull reinforced his caution. More “tooth prints” and claw scratches around the door and windows suggested we sleep with the plank door bolted and rifles loaded at bunkside. Even the edges of the rafters showed bear damage.

Chase Gallaher scans the lakeshore for moose.

“They try to break in everywhere. Grandpa tried plywood cabins, but they tore them apart. The only construction that stands up to them are these two-by-twelve planks, all tightly fitted and chinked.”

We trailered the canoe down to the lakeshore and splashed it through the flooded willows for an evening hunt. With the offshore breeze in our faces and a nearly dead silent approach, it seemed the perfect tactic. We paddled within range of beavers, muskrats, otters, swans and ducks. But no moose. Not on the north shore, not in the east bays and backwaters. Not near the cabin where a client had taken a big bull the year before. It was as if the moose had gone into hibernation. The place was dead.

It came alive the next morning.

“That sounded like a moose antler,” Betsy said, water dribbling from the paddle paused in mid-stroke. We held our breath as the canoe glided. And then another ringing slap of bone on bone. North shore! Two bulls fighting!

“That sounded like a moose antler,” Betsy said, water dribbling from the paddle paused in mid-stroke. We held our breath as the canoe glided. And then another ringing slap of bone on bone. North shore! Two bulls fighting!

The sounds of battle continued as we churned our way north, each crack and whock urging us faster. The bow slithered into the sedges and we stepped into the fray. From the sounds of clattering antlers, our quarry couldn’t have been more than long arrow flight away, an easy trip for the 150-grain Swift Scirocco poised for launch in Betsy’s 7mm-08 Kimber Adirondack. All she needed was a clear view. But we didn’t even have a cluttered view. Only the sounds of battle behind a thick screen of willow and poplar limbs. And then even those ended.

“Let’s get to that opening there,” Chase whispered, nodding toward a distant bog. The breeze was perfect, moose to hunter. Chase led the way, canoe paddle in hand. He would use it to mimic a rocking moose palm, rake a sapling, then post it as a shooting platform for Betsy’s rifle. But first we had to see the bulls. And we hadn’t heard them for 10 minutes.

“They couldn’t have smelled us, could they?” Betsy asked.

“No. The wind’s good. And they couldn’t see us if we couldn’t see them. Wait….”

And then, agonizing minutes later, antlers clashing. Deeper into the woods. The fight must have temporarily turned to a chase. But now they were wrestling again. Chase interrupted it with a moan. A long, loud, pleading, nasal whine to remind the combatants what they were fighting for.

A pregnant pause. And then the snap of limbs. The thump of hooves. They were coming. At a run.

The usual strategy was to beach the canoe, then set off on foot to key calling areas.

Betsy’s rifle was across Chase’s arm and against the paddle shaft when antler tops arose behind a small spruce no more than 60 yards out. There was clear meadow on both sides of it. The moose just had to take a step or two either way and the shot would be on its way. And then I felt the cool, unwelcome caress of wind on my nape. It carried the ultimate warning to our quarry.

You’d be amazed how quickly a towering, plodding, rut-stupid bull moose can pirouette and flash through the trees. There it was for a split second between two spruce, chest briefly exposed. But too briefly. And behind it the other bull, this one carrying antlers twice the size of the first, dashing along the big woods edge. And gone. Both of them.

Chase wasted no time complaining. He led Betsy at a trot across the meadow. They stopped at one of the seismic trails, a long, narrow chance in the endless blanket of forest.

“Shoot when he steps into the trail.”

And then he did, black and massive, deep-chested, antlers like plywood signs advertising a dream hunt in the north woods, conjuring every calendar illustration, every magazine cover, every romantic vision of the voyageur moose hunter ever imagined.

The magnificent bull stopped at the edge of the obliterating woods, paused and turned its massive antlers, its breathtaking palms toward us for one confirming, last glance.

There was no time for a rangefinder. Two hundred yards? Three hundred? Three-fifty? Betsy had too much respect for this bull to chance a quick, long shot at unknown range.

“How far? she asked, the frustration evident in her tone. And then two steps of those long, pale gray legs and he was gone, swallowed by the brush that had fed and protected him from predators four-legged and two for seasons after seasons. The bull of the woods. The bull of dreams. Haunting ours still.

This book will make you laugh. It is full of stories you’ll want to read again, and again. You’ll tell your friends about it. Thinking about it will make you smile during boring meetings. People will wonder what you are up to. On a bad day, when you’ve screwed up at work, your wife is mad at you, and the kids are sick, this book will give you half an hour’s respite. It will take you to a place of adventure, danger, and humor, all woven together by one larger than life character. I had to get all that down fast, because it’s important. I’m not a writer, and I don’t know how long I can hold your attention.

This book will make you laugh. It is full of stories you’ll want to read again, and again. You’ll tell your friends about it. Thinking about it will make you smile during boring meetings. People will wonder what you are up to. On a bad day, when you’ve screwed up at work, your wife is mad at you, and the kids are sick, this book will give you half an hour’s respite. It will take you to a place of adventure, danger, and humor, all woven together by one larger than life character. I had to get all that down fast, because it’s important. I’m not a writer, and I don’t know how long I can hold your attention.

Dr. Larry GatesThe stories in this collection are true. In some instances, the names have been changed to protect the innocent and the not so guiltless.

With most days of the past forty-seven years spent in Alaska, the thirty-six stories in this collection are connected primarily with Jake’s guiding activities in the Great Land. These stories were selected for their humorous content.

This selection of tales is trivial, eclectic, and of minimal redeeming value. But there may be some valuable bits of information, if one looks for them. These stories attempt to entertain readers, to give them a giggle, or at least a wry smirk. Buy Now