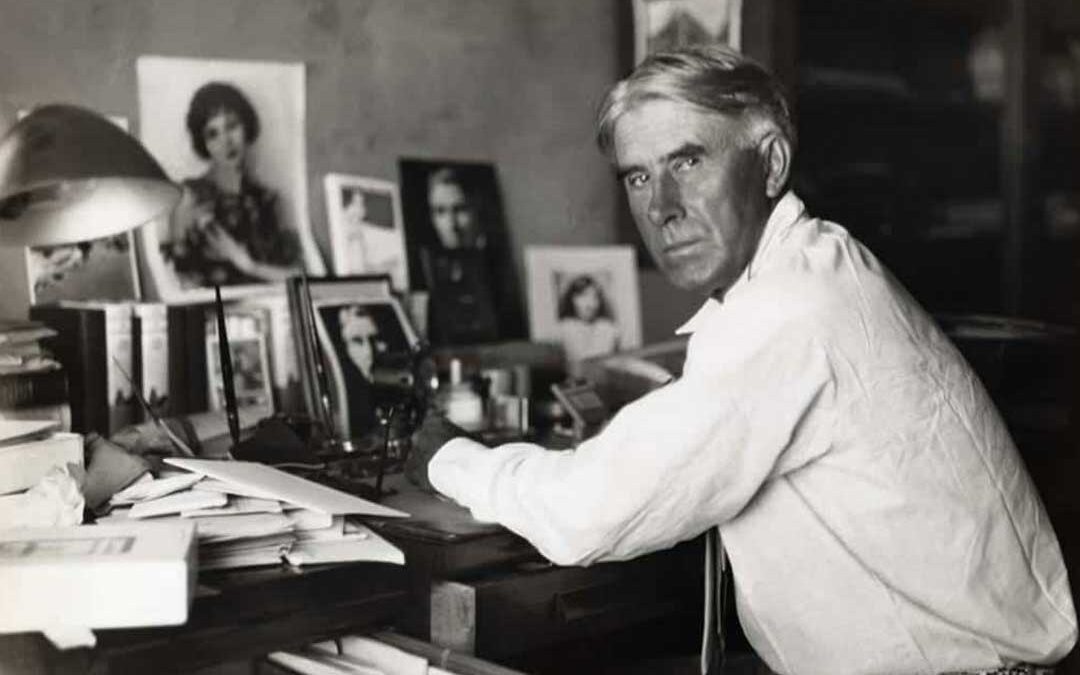

There are many facets, some of them controversial or even contradictory, to Zane Grey’s career: oddball youngster with an overbearing father, exceptionally skilled collegiate baseball player, disillusioned dentist, struggling and often depressed young writer trying to find himself, author of nicely crafted and enjoyably readable books for boys, daring adventurer, serial philanderer, adoring father, peerless novelist in the genre loosely described as “Westerns,” pioneer in the film industry and visionary.

Most of all, though, when it came to his personal passions, Grey was an angler for the ages. Indeed, over much of his career, he committed himself to writing tirelessly so he could fish the waters of the world. What follows is a look at the literature by and about Zane Grey, primarily in the context of his life as a fisherman.

Over the years Grey has been the subject of numerous biographical studies, with some of them bordering on sheer hagiography while others are probing and perceptive. For anyone seriously interested in studying the man or delving into the daunting task of accumulating a representative collection of his writings, the logical starting point is with bibliographical treatments of his massive literary output.

A husband-and-wife team of booksellers, Edward and Judith Myers, produced useful little booklets in the 1980s with the title A Bibliographical Check List of the Writings of Zane Grey. Carlton Jackson’s Zane Grey (1973) in the Twayne’s United States Authors Series is useful but far from complete. G. M. Farley’s Zane Grey: A Documented Portrait (1986) has its shortcomings on the biographical side, but the 40-odd pages devoted to bibliography and filmography are most helpful.

Veteran sporting scribe George Reiger devoted considerable attention to Grey in compiling anthologies featuring outdoor-related aspects of his career in Zane Grey: Outdoorsman (1972), The Zane Grey Cookbook (1976), Undiscovered Zane Grey Fishing Stories (1983) and The Best of Zane Grey (1992). They show considerable research and, thanks to their subject matter, are likely to be of special interest to readers.

On the biographical side, until fairly recently Frank Gruber’s Zane Grey: A Biography (1970) was considered the standard life of Grey. Recruited by the Grey family to write the book, Gruber produced what is in many ways a problematic treatment. It is poorly documented, contains information that is not factual, and as one modern critic states, “important information was sloppily handled and intentionally ignored.”

An earlier effort, Jean Karr’s Zane Grey: Man of the West (1949) is little more than a potboiler, and much the same can be said of Norris F. Schneider’s Zane Grey: The Man Whose Books Made the West Famous (1967). Other treatments include Kenneth W. Scott’s Zane Grey: Born to the West (1979), Carol Gay’s Zane Grey, Story Teller (1979), Ann Ronald’s Zane Grey (1975), and Candace Kant’s Zane Grey’s Arizona (1984).

G. M. Farley, a great and well-intentioned admirer of Grey who was also an avid collector of the writer’s works and something of a bibliophile, started a periodical entitled The Zane Grey Collector. In time that led to two books, the privately printed The Many Faces of Zane Grey (1991) and Zane Grey: A Documented Portrait (1996).

Then, in 2005 there came the book that must be reckoned as the definitive life, at least at that point in time, as well as a work that turned the world of Zane Grey studies and enthusiasts upside down. This was Thomas H. Pauly’s Zane Grey: His Life, His Adventures, His Women. While scholarly in nature and published by an academic press, it makes fascinating reading. Suffice it to say, the book is likely to change any and all preconceived notions you had about this literary icon. At times it is almost as if a suitable subtitle would have been “The Scribe as Satyr.”

Pauly’s book follows Grey from Arizona to Australia, from gritty days in the Grand Canyon to the glories of the Galapagos, with insight and delight. Seldom does an academic book appeal to the general public, and as a recovering professor I maybe have a clearer window on this than most. This one is a striking exception, and every serious student of the man should read it.

Of course, the same goes for Grey’s ventures into angling literature. Altogether he wrote eight books devoted wholly or in large measure to fishing, all of them beginning with the words “Tales of.” They were, in chronological order of first publication, Tales of Fishes (1919), Tales of Lonely Trails (1922), Tales of Southern Rivers (1924), Tales of Fishing Virgin Seas (1925), Tales of the Angler’s Eldorado, New Zealand (1926), Tales of Swordfish and Tuna (1927), Tales of Fresh-water Fishing (1928), and Tales of Tahitian Waters (1931). Add more than three dozen articles for Field & Stream; another dozen-plus for Outdoor America; a number of contributions to Outdoor Life, Recreation and Sports Afield; along with his wonderful short story “The Lord of Lackawaxen Creek” (first published in Outing), and you have a body of work that places him in the first rank of American angling writers.

During Grey’s lifetime, literary critics, whether reviewing his novels or his fishing books, were surprisingly unkind. Yet viewed from today’s perspective, his work has about it a durability and charm, which suggest that most of the reviewers were pointy-headed pedants more interested in burnishing their own images than in getting to the root of what made Zane Grey’s writings so appealing.

To me, the answer is simple. Whether fishing or riding the purple sage, he takes his readers along with a sense of adventure, a manly zest mixed with just the right touch of delicious daring, in a fashion unconstrained by the bonds of time. His work is enduring and to this reader at least, often endearing. You can view his personal peccadilloes as you wish. But one thing is certain: Grey remains eminently readable.