Exhausted and dehydrated, Stanczyk felt as if he had been watching it all in a dream.

Richard Stanczyk grew up on the water. His childhood home in Miami was located adjacent to a canal that led to the ocean. The salty brine got into his veins early in his life, became part of him and served as his first love. Growing up in south Florida during the 1960s, Stanczyk’s teenage years largely consisted of fishing, dreaming about fishing and going to school.

Like many kids their age, Stanczyk and his buddies had big plans for the high school prom. They reserved tuxedos, rented a limo, and had a suite waiting for them and their dates at the luxurious Fontainebleau Hotel. For the girls, the formal ball was the biggest event to occur in their young lives. For the boys, it was more of an endurance test to earn them “the party after the party.”

On the morning of the big day Stanczyk awoke to gorgeous south Florida sunshine. Temptation wasn’t long in coming. He reasoned there would be plenty of time to get in a little fishing before all the pomp and circumstance of prom night. Despite stiff resistance from their dates — who believed they were out of their everlasting minds — Stanczyk and his two buddies, Jeff and Tommy, headed out of Government Cut in south Miami Beach on his 21-foot Fibercraft powered by 80-horse Volvo engine. If all went according to plan, they’d catch a mess of fish and get back by noon with plenty of time to spare.

About five miles offshore, the boys discovered a series of promising weed patches floating along the edge of the Gulf Stream. Targeting the yellow flotsam, they soon hooked and landed a number of “dolphin fish” (mahi-mahi), filling the cooler in no time.

Here it was, only 9 a.m., and their outing was already arousing success!

When the action began to wane, Stanczyk figured they still had a little time left to kill, so he turned his attention to larger prey. He took out a swimming mullet rig and attached it to his 6/0 Penn Senator reel, the heaviest outfit he owned. Stanczyk tossed the bait into the water and attached the 50-pound line to the outrigger. His hope was to tempt a sailfish cruising in the area. To someday do battle with one of the greatest fighting fish known to man — in an era when such thrills were still the exclusive territory of famous personalities such as Zane Grey and Curt Gowdy — was his foremost dream.

Opportunities of a lifetime are rarely scheduled in advance, and this was no exception. The bait had scarcely descended below the surface before it was crashed hard and immediately taken deep. Struggling to hold his excitement in check, Stanczyk waited for the fish to swallow the bait, then set the hook. All hell broke loose.

Line peeled off the Penn reel at incredible speed. It was apparent very quickly that this wasn’t a dolphin or the typical sail. Not only was it fast, it was heavy.

As more and more line tore off the reel, disappearing into the blue-green depths, there seemed to be no way to stop the fish or even slow it down. Something needed to be done fast or the battle would be over all too quickly. So the boys started up the engine and gave chase.

Stanczyk settled into a makeshift fishing chair that his grandfather had fashioned. It consisted of a simple lawn chair with a gamble attached to it. The contraption would prove to be the most beneficial tool available to young Stanczk this day, allowing him to get just enough leverage to fight the fish. Yet even with the boat in gear, the fish was continued to take out line. The young angler clamped down the drag as far as it would go, but the fish just seemed impervious to it.

An hour into the battle, the boys found themselves about five miles from where they’d started. The searing Florida sun was beating down on the youths. Stanczyk began to feel the strain throughout his body. Adding to his fatigue was the feeling of complete powerlessness; he could only speculate as to what he was dealing with on the far end of the line.

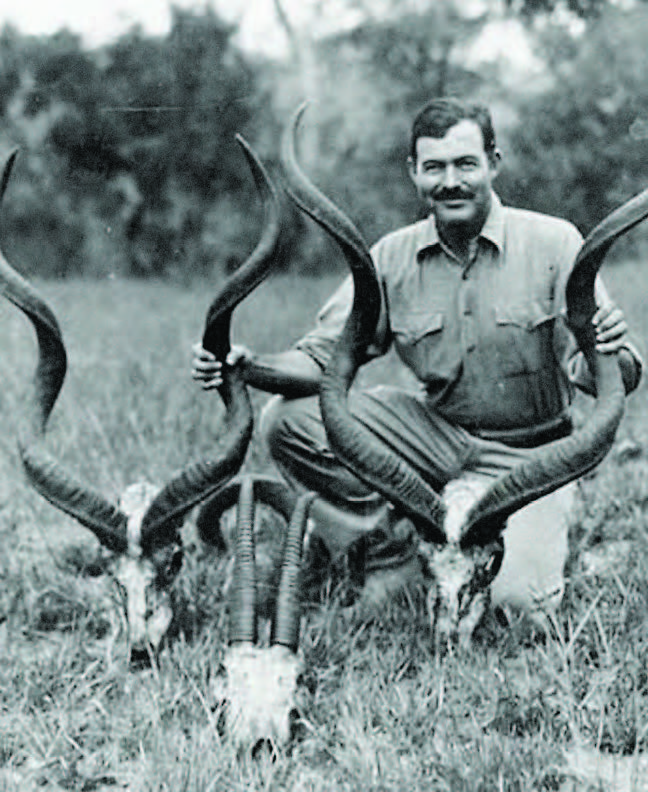

During a moment of reflection his thoughts shifted to a recent English class reading assignment. As if by divine design the book had been The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway. It was one of the few novels Stanczyk had ever read and actually enjoyed. Little did he know just how close his experience would ultimately minor Hemingway’s classic.

Ten miles farther and two hours later, the boys started to wonder if they were up against more than just a battle-hardened fish. If inclinations were correct, this could very well be a record-breaking catch; truly, a once-in-a-lifetime catch. Be it by luck or by fate, there was no giving up. Moving at a consistent pace with the fish and current, the boys stood united in youthful exuberance and the spirit of adventure.

As the clock ticked past noon — the boys targeted time of return — the huge fish continued to tow the boat northward. By now, Stanczyk’s straining back muscles were on fire. The searing, unrelenting heat beat down on the boat, cooking him on the outside and dehydrating him on the inside.

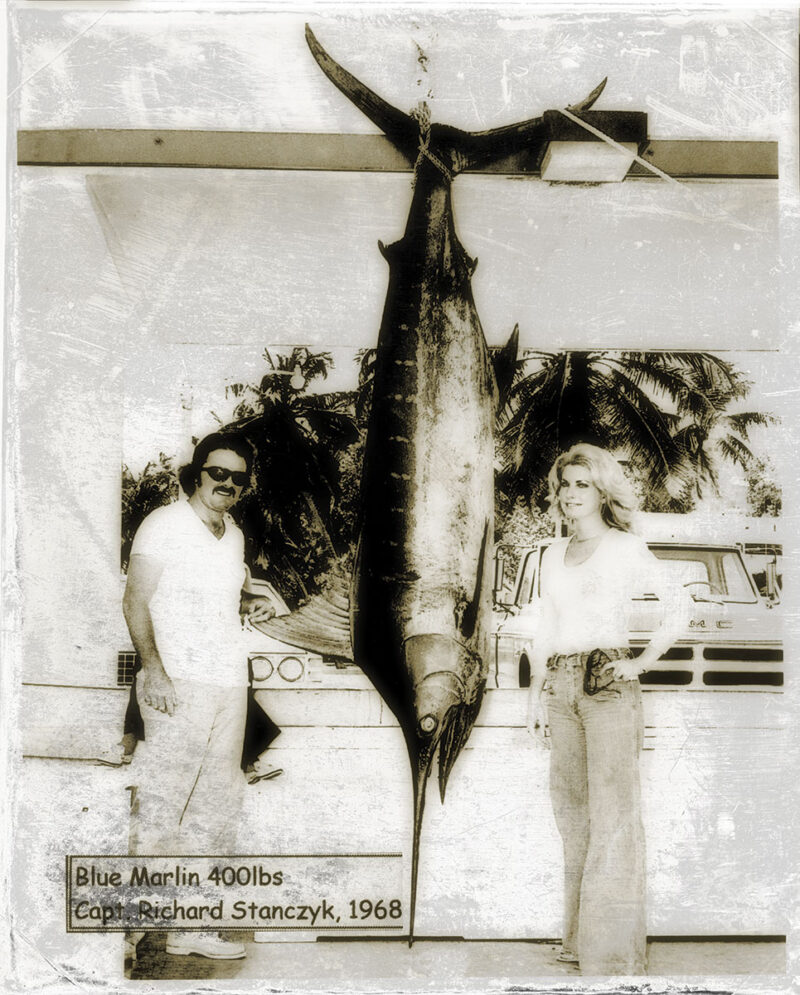

He felt the fish lunge and shake on the end of the line, then changing tactics, it bolted in a new direction. Suddenly, on the opposite side of the boat the surface exploded in a starburst of salty white foam as a magnificent blue marlin leaped high above the water.

The boys shouted in amazement as the fish thrashed and twisted across the surface, seemingly defying gravity in a frenzied dance that continued for more than 100 feet.

This marlin’s new tactics energized Stanczyk and his friends. At last they knew what they were up against. And so began the next round in their epic struggle of endurance, strength and determination.

After the stunning aerial display, the fish sounded deep and sprinted away at an amazing speed. Richard tried to keep up as best he could, but as the marlin charged, the line was now “stuck in the water,” moving in a different direction than the fish. Stanczyk reeled at a frantic pace, but he couldn’t seem to catch up. He started to worry this might be the end, but his persistence soon paid off as he caught up to the fish and began reapplying steady pressure. The northbound battle of give and take resumed.

Close to four hours and 12 miles into what had become a major campaign, Stanczyk was neither gaining nor losing ground. By all appearances they were in a standoff. He simply could not tum the fish.

During this moment of realization, the question of the day was finally raised among the friends: Was it time to cut the line while they could still make it to their formal engagement? With so much time, effort, blood and sweat invested in this fish — potentially the fish of a lifetime! — all on board agreed to give it a little willie longer. Hopefully they’d be able to subdue the fish and only be “a little late” for the festivities. The clock was ticking, the pressure was on.

Two o’clock came and went, and the fish began changing speeds. Then suddenly, the line rose once more from the depths and the magnificent blue marlin broke the surface in a whitewater explosion, shaking and churning in a deliberate, slow-motion, semi-circle behind the boat. The boys watched in awe and admiration, their mutually observed silence understood by all. There was no further mention of quitting.

Six hours into the fight, the experience was transitioning from a test of physical endurance into something more akin to torture. Stanczyk’s fingers were literally locked around the rod, while racking waves of pain conspired against him. The scorching sun continued to beat down, burning his exposed skin to a bright, angry red. They had no sunscreen, so Jeff provided help and support where he could. One idea was to spread peanut butter over Stanczyk’s exposed skin to help protect him from the sun’s blistering rays.

Stanczyk, with peanut butter smeared over his face, nose, lips and ears, was fighting fatigue, pain, guilt and now a new emotion: doubt. Eighteen miles into the ordeal and he just couldn’t gain any advantage at all. The fish was outlasting him and he knew it.

Then another thought crossed his mind: What were they going to do if they actually got the fish to the boat? They had no gaff, no winch and this was the largest living creature the boys had ever seen. Their only hope was that the marlin would just up and die of exhaustion right there alongside the boat. Then they could simply tie it up with the anchor rope and triumphantly motor to shore, much like Santiago, the old man in Hemingway’s novel, but without the voracious, marauding sharks.

Well into the seventh hour searing heat, pain and absolute exhaustion were rolling over Stanczyk in heavy, debilitating waves. Then Tom brought up a vital, burning question that hit like him a sledgehammer in the stomach: What about the fuel? Did they have enough gas lift to get home? The short answer was no. In all the excitement, they had neglected to keep an eye on the gas gauge.

The situation was serious. If they cut their losses now, maybe they could avoid drifting off to Carolina or Europe and make it back into shore. Out of drinking water and short on fuel, it was time to force an end.

Stanczyk grabbed a pair of pliers and began to apply steady pressure to the drag, clamping it down as tight as he could. He could only hope the fish was exhausted enough to succumb. Little by little the line stretched, then stopped going out altogether.

Encouraged, Stanczyk began regaining line. After about 50 feet the champion blue marlin bolted skyward once more, crashing the surface and soaring 15 feet into the air. It was the last time the boys would ever see the fish. With that final defiant leap, the line parted. The fish was gone, its freedom well-earned.

Exhausted and dehydrated, Stanczyk felt as if he had been watching it all in a dream. He collapsed into the lawn chair and reflected in silence. Time and perception slowed to a dreamy crawl. Minutes passed. When he finally came out of his trance, he attempted to give reason to the day’s events, promising his friends it would be different next time: There was still another monster out there, one even bigger. They would find it and they would come out on top! Stanczyk likened his exhausting duel to what Captain Ahab might have felt for the big white whale in Herman Melville’s seafaring classic Moby Dick.

With an end to all the excitement came the emotional crash of reality. Fuel was low and the entire night’s social calendar had been sacrificed hours ago. They had no radio and the concept of cell phones was the stuff of science fiction back then. Their location was somewhere north of Fort Lauderdale, more than 30 miles from where the battle began. Luckily they were just six or seven miles offshore. They began motoring in toward land, and once they got close enough, they turned southward toward home. Their hope was to find a inlet harbor, maybe around Pompano Beach.

To the boys’ credit and good fortune they found an inlet as the sun was beginning to set. Slowly they motored into the Bay, and just as darkness fell the motor began shifting and stuttering, then finally quit for good. Adrift and out of fuel, at least they were within the safety of the bay.

Stanczyk, drained far beyond his physical, emotional and spiritual limit, simply closed his eyes. With visions of the great blue marlin replaying in his mind, he began to doze.

Stanczyk was awakened by a light bumping sound coming from the bow. The boys had drifted up against a seawall within the bay, right in front of a large oceanfront home. Help was now a mere phone call away. Concerned about the owner’s likely reaction to a beaten-down, ragged-looking refugee covered in peanut butter walking up to his back porch, Jeff pulled the assignment of first contact. When told of the boys’ amazing story, the homeowner was enthralled.

Stanczyk was awakened by a light bumping sound coming from the bow. The boys had drifted up against a seawall within the bay, right in front of a large oceanfront home. Help was now a mere phone call away. Concerned about the owner’s likely reaction to a beaten-down, ragged-looking refugee covered in peanut butter walking up to his back porch, Jeff pulled the assignment of first contact. When told of the boys’ amazing story, the homeowner was enthralled.

Stanczyk made the phone call home to his father, who told the boys that he’d pick them up and take them home. With that, the boys gave the homeowner the mahi-mahi they’d caught earlier as thanks and said their goodbyes.

During the ride home, Stanczyk considered what to say to his date. After careful consideration he decided to go with the truth — well, a version of it anyway: The boys had run out of gas and drifted in the Atlantic until they were finally rescued. In the end, they missed the dance, and all the formal dress, photos and fuss that came with it. But they still made it to the after-party at the Fontainebleau Hotel. No mention was ever made of the great marlin. Why ruin a good thing?

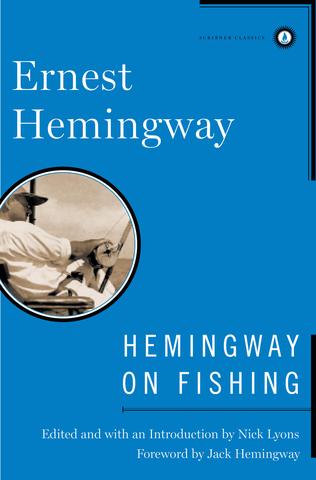

Hemingway on Fishing is an encompassing, diverse, and fascinating assemblage. From the early Nick Adams stories and the memorable chapters on fishing the Irati River in The Sun Also Rises to such late novels as Islands in the Stream, this collection traces the evolution of a great writer’s passion, the range of his interests, and the sure use he made of fishing, transforming it into the stuff of great literature. Buy Now

Hemingway on Fishing is an encompassing, diverse, and fascinating assemblage. From the early Nick Adams stories and the memorable chapters on fishing the Irati River in The Sun Also Rises to such late novels as Islands in the Stream, this collection traces the evolution of a great writer’s passion, the range of his interests, and the sure use he made of fishing, transforming it into the stuff of great literature. Buy Now