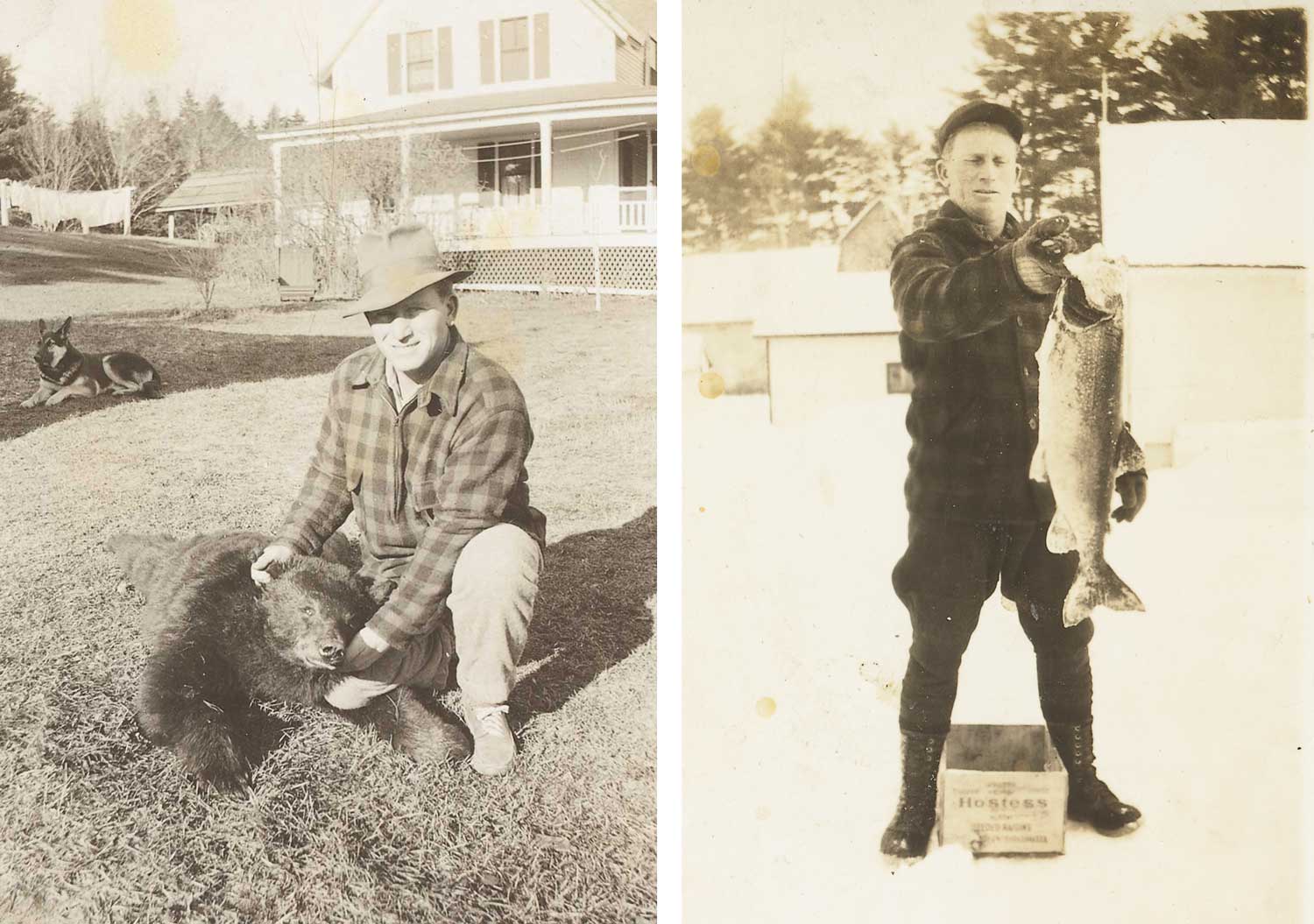

Woodie Wheaton only had a 10th grade education, but got his PhD in the woods and waters of Washington County, Maine. Beginning at age 14 and continuing for the next 68 years, he was recognized as one of the most skilled and respected Registered Guides in the state. “Woodie had no peers,” stated veteran guide Earl Bonness at Woodies graveside service in 1990.

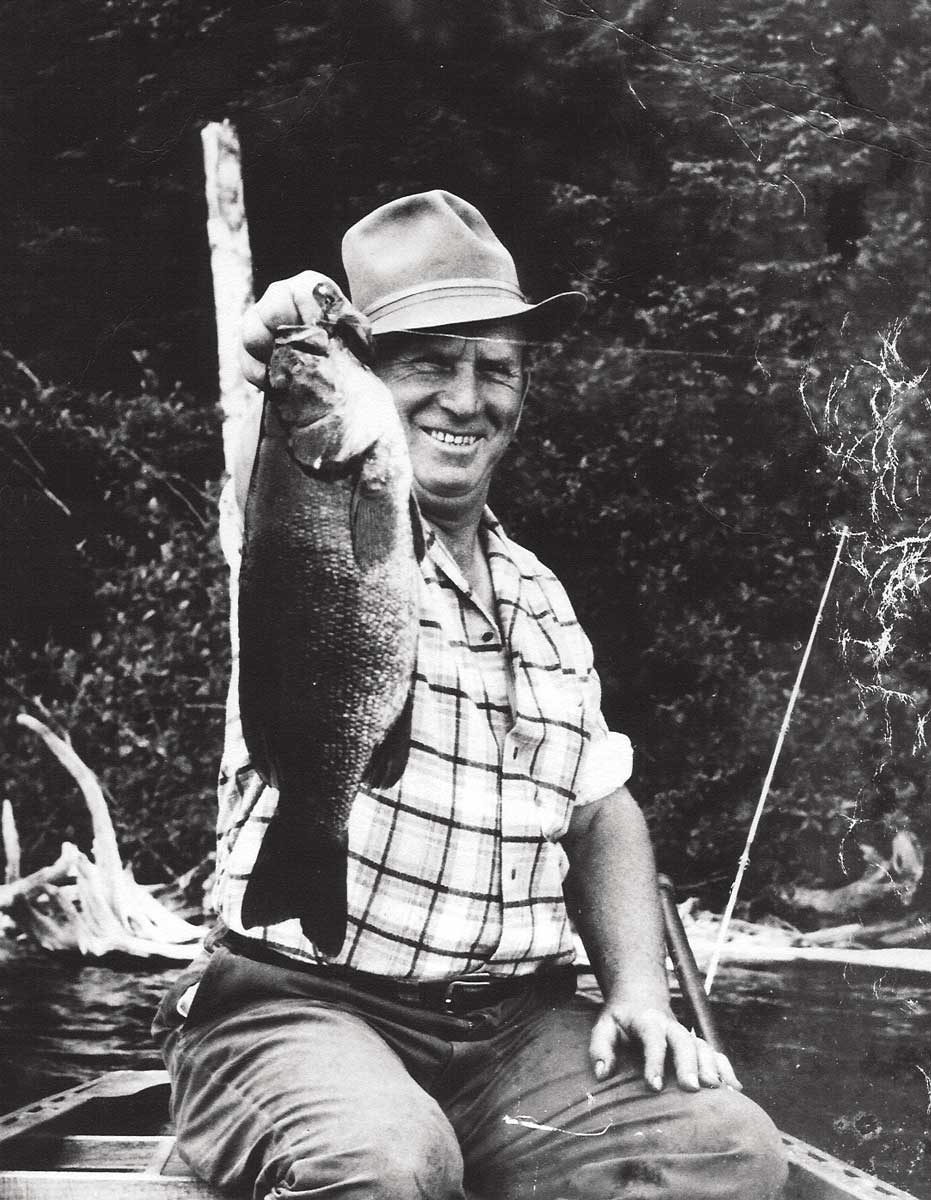

Woodie passed away more than 20 years ago, and there hasn’t been a day gone by that I haven’t thought of him. He was a legend in his neck of the woods, a pal, hero and mentor to many. Woodie was well known for his wonderful sense of humor and his skills as a canoe builder, axe man, woodsman, fisherman, hunter and guide. He could pole a canoe upriver, and cut and split a pile of wood that would kill most men. He was experienced with a peeve, cant dog and pick pole, and in his younger days could run across a boom of logs. With superb accuracy he’d cast a fly or “popping bug,” or flip a spinning rod underhand to hit a smallmouth spawning bed dead center.

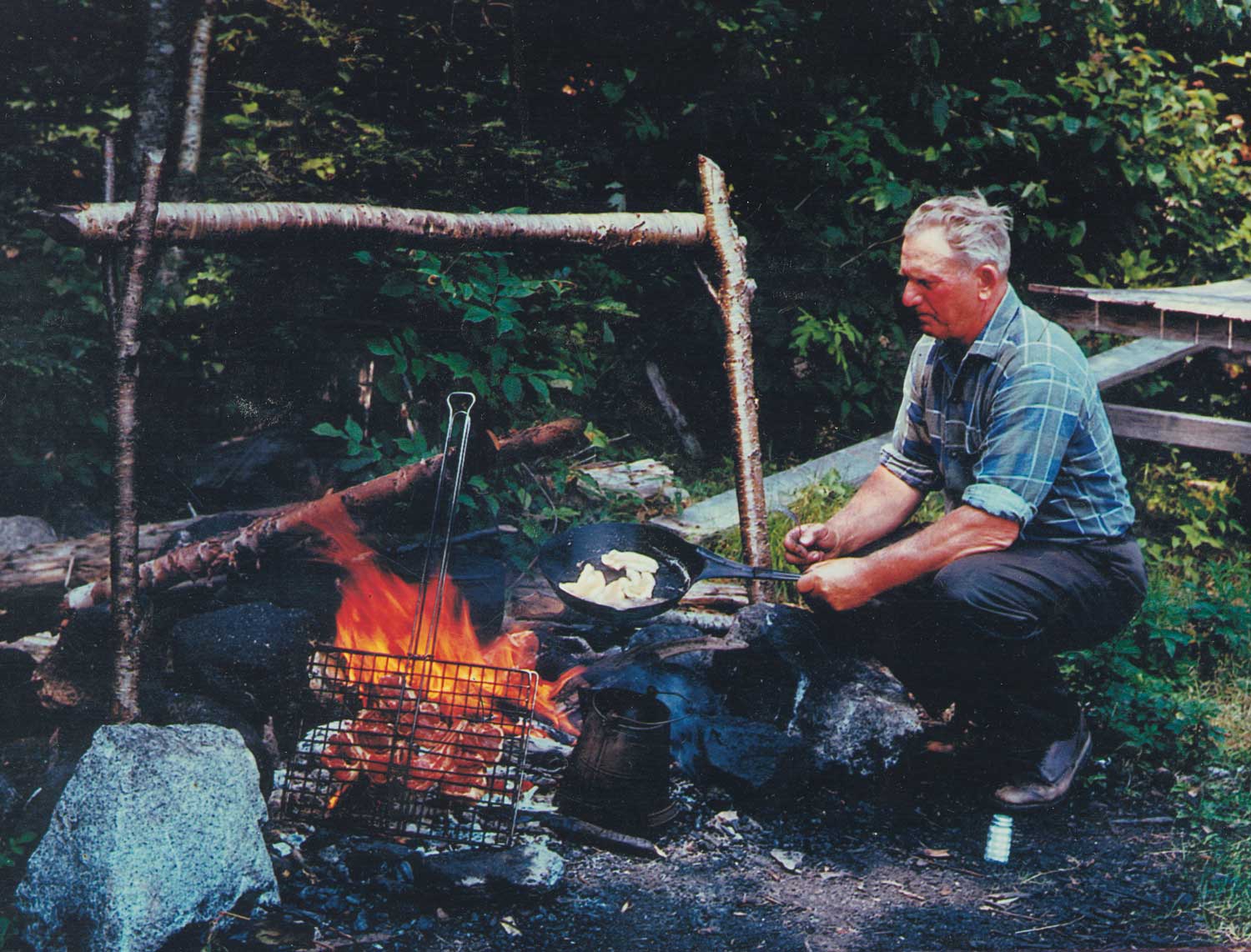

Woodie could motor his canoe over a fallen log, build a campfire in the rain, make a basket from birchbark, and find crayfish or frogs under the rocks along shore. As a young man he could set a gill net (while it was legal), drive a team of horses, cook salmon in his own hand-built smokehouse and over a campfire and whip up a batch of biscuits on a moment’s notice. He built many a canoe by gathering and steaming the cedar himself; he built his own sporting camps and shot deer to feed his family.

Over the years Woodie sent me many letters, some penned at his home in “good ol’ Forest City,” Maine, others from his winter residence in St. Petersburg, Florida.

The following excerpt, from a letter written on a simple lined tablet, brings a chuckle and a little moisture to my eyes every time I read it.

St. Pete – Monday. Hi – Enclosed, best cartoon of the year. Also – great news – knocked the shit out of a black monster last night on my usual trip to the bathroom at 3:00 a.m. I laid plans on my approach to the kitchen, carefully picked up the Raid bomb and as I turned on the light, the monster revved his motor and jammed the throttle to the floor in a getaway attempt. I fooled the Bastard by leading two lengths and making a Bulls eye. He is now reclining in the garbage can, dead as hell, and here I am gloating – Damn all Palmetto bugs. May go to hear the Barber Shop boys at the Bayfront Center soon – only thing that’s been fit to see there all winter. My best, Dad

Dad’s approach to guiding was always to plan ahead to outwit the fish, determine the whereabouts of that whitetail buck, or be somewhere near shelter when a storm hit. There were instances when he was the one who located and dragged up drowned men. It was Woodie who would work long into the night to patch a canoe – canvas or fiberglass –and who could expertly cut and remove a treble hook from some glassy-eyed sport.

While deer hunting one fall Dad was shot in the pant-leg near his hunting camp, where he often carried in supplies by moonlight. Woodie knew who fired the errant bullet, but he kept it to himself because he didn’t want to embarrass anyone.

Again from St. Petersburg he wrote:

Hello People – We’ve had a lot of miserable rain and wind . . . this morning 36 degrees. Been fishing twice. Caught a few mongrel bastards, also hit a few quivering golf balls. Am busy as hell, loafing my head off – Can’t get up enough ambition to go to the bathroom. Want to thank you for the nice shirt and wonderful book. Real “thorty”of you. Keep working hard, save your money and you will probably turn out to be the richest people in the graveyard – All my love, Dad.

Woodie was born in the Down East fishing village of Grand Lake Stream, Maine, on August 18, 1909. He learned his trade from his father, Arthur, a canoe builder and well-known guide. He was just Woodie – not Woodrow, Woodruff, Woodson or even Woodworth, his Christian name – to all his “sports,” friends and colleagues. Many of his boyhood friends, some of whom were Passmaquoddy Indians, grew up guiding, as it was the natural thing to do in those days.

Woodie’s career began when a sportsman offered him a month-long guiding job that included taking care of the man’s son. And so, at 14 Woodie applied for and received his first guide’s license. Back then, he would scrape together a few dollars by collecting a bounty on a porcupine, sell a catch of pickerel for the market, or trap “mush’rat” or mink. He even sold venison to help put grub on the table. During the Great Depression, Woodie counted himself fortunate when he earned $2.50 a day.

An excerpt from his October 1st, 1989 letter captures those times.

Want to thank you for the book [Down East Game Wars] brought back a pile of memories. When I was growing up we heard plenty about that outfit in Wesley and Crawford – we had plenty of poachers at GLS [Grand Lake Stream] but not to the extent those fellows carried on. I had heard about the hayrack they used to haul deer and I guess I wasn’t wrong. Also heard of Graves, who shot those wardens down there. Even in my day the Game Warden wasn’t too popular. Finished on the lake yesterday – wind blowed like hell and came in for a late lunch as they were leaving at 3:00. Fellow from southern Maine paid good with three Franklins for three days. Came up with forty days for the season and earned more money than I would ordinarily make in the whole season. There sure is one hell of a lot of difference between $100.00 and $2.50.

Meat on the family table sometimes came from jack-lighting deer, and every morsel, including the neck meat was used, cut into roasts, steaks or ground up into mincemeat or hamburger.

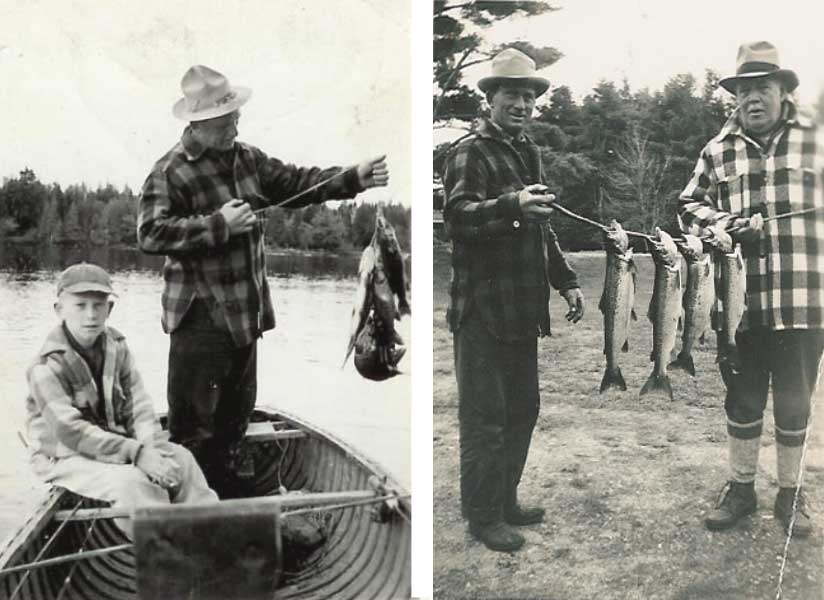

Comfortable in his square-stern “Grand Laker” that he built himself, Woodie would devote the entire season – from the first of May 1 til the end of September – chasing landlocked salmon and smallmouth bass. His reputation skyrocketed in 1960 when the July issue of Outdoor Life published “Best Smallmouth Bass Fishing in the World,” by Wynn Davis, and it spiraled even higher when another Davis article, “Catching Landlocked Salmon” appeared in the summer of ’64. Woodie would later be featured on Bud Leavitt’s television show, Woods and Waters, which along with numerous newspaper articles earned him legendary status among Maine guides.

Woodie’s profession demanded responsibility, planning, knowledge and a commitment to giving each “sport” a solid day’s effort – the best you knew how – to find fish or game.

Each morning he would meet the client after breakfast at the lodge, ready to head out with lunch basket, bait and a full tank of gas. He took a thoughtful approach to each day, not wasting time running from place to place. He had already taken into consideration the wind speed and direction, the weather conditions, the places he wanted to fish, and the expertise and experience of his anglers.

When on the water, Woodie could often be found digging into his old tackle box, selecting a proven tandem Grey Ghost streamer that he modified with his by cutting away some of the heavy throat hackle. Or he rummage around for a certain spoon, like the Mooselook Wobbler he doctored up with red paint from an old bottle of nail polish. While he worked, he would be trying to decide whether to slow-troll with sewed baits or quicken the speed of his outboard to make the Mooselook pulsate just right.

Knowing when and how to use a certain lure or bait often made the difference between a full stringer or heading home emptyhanded. Another one of his letters makes the point.

Good ol’ Forest City, May 20, ’83. Dear all – Jack Knives received and delivered. Missed my seventh black bird with the air rifle. Perhaps should have stuck with the shotgun.

Pete’s blue fly placed back in the box – mooselook wobbler doing better. Promised Bev and Dale a good kick in the ass if they forgot to thank you for the knives – Enclosed a check for the air gun – Too early for charity and am working now – My best to all the little boys and girls and Doris – Be a good boy and wear your boots – My best, Dad.

Woodie and Ruth faced one of their biggest decisions in 1951. It would have a profound effect on their family for the rest of their lives and establish a legacy for those that followed. Woodie wanted to build a sporting camp on East Grand Lake, but had no money, no property and no management experience. So, with money borrowed from his father-in-law, he struck a deal with Ormond Cummings who owned some old log cabins on the lake.

Wheaton’s Lodge is still a first-rate fishing destination, now operated by my brother, Dale, and wife, Jana. Even today anglers can expect to find the same serenity, solitude and high-quality experience that Woodie first offered a half-century ago. They still fish from Grand Laker square stern canoes, each with a skilled guide who prepares a delicious shore lunch.

Dad taught me about the woods, about pat’ridge, squirrels, rabbits, deer and ducks, He showed me how to paddle a canoe, the right places to fish, how to filet fish and much more. I was only 7 when he took me on my first deer hunt. In the years to come I would arrange a number of hunting trips for him.

“Forest City, Me. Thanks again for all the good things you made happen on our trip. We have had boiled duck, roasted duck, fried duck, and tonight duck soup. All good and we enjoyed it. I have filled my teeth with steel so I shouldn’t need any dental work for some time – Best to all the gang. Love-Dad”

In July 1990, on the day before he died, Woodie and Lance were guiding several fishermen on Mud Lake. Dad was tuckered out after three straight days of guiding – motoring his “sport” around the lake and hauling his canoe in and out of the water. But his mind was still sharp, which enabled him to provide good fishing for his anglers.

In his last letter, dated June 1, 1990, he mentioned that he was working on a “dancin’ man” for me. Made of pine, with pinned joints to let the legs flip and flop, the “dancing man” was a common sight in the old lumber camps where it was used to entertain woodsman on cold winter evenings. I had always wanted Dad to build me one.

Forest City, June 13, 1990. Hi Chum – Guess Lance and Dale have both full camps. We have been taking some swell salmon on Spednic. Biggest 7 lbs 7 oz. I’ve caught 3 in the 5 lb class and surely they fight like the old times. Have your “Dancin’ Man” ready for you. Mom painted his clothes on and he really looks sharp.

Thanks again for remembering the old people – I don’t mind getting old, but to get stupid at the same time – hell of note. My best to all. Always. Dad

I received the call from mother, at dinnertime on July 14, 1990. Something awful had happened, she said. It happened on a woodland road about two miles from home, just the way he wanted it – no suffering, in the woods he loved, his heart would go no more. Dad’s passing was especially tough on mother who had lost her companion of more than 50 years.

Gone was the grandest guide in the State of Maine. He left behind a namesake, Woodie Wheaton Island, proclaimed by the Maine State Legislature, where he lunched with his “sports” for so many years along the lake he considered his very own. His sons, colleagues and friends created the Woodie Wheaton Land Trust, an effort to protect for future generations the pristine lakeshore and woods he loved.

Today, my “dancin’ man” looks at me from the bookcase and Dad’s hat rests on a peg above my desk where I have stored his letters, each a treasured memory. Dad, we miss you.