Dubbed the “Dark Continent” by Victorian explorers who were fascinated by its geographical mysteries and incredible abundance of game, Africa has been the setting for a massive outpouring of literature of interest to sportsmen. The latter half of the 19th century on into the pre-World War I portion of the early 20th century gave us grand writers such as Cornwallis Harris, Samuel Baker, Fred Selous, Theodore Roosevelt, John Millais, James Sutherland, J. H. Patterson, Cotton Oswell, C. J. Andersson, and a host of others. Yet the impressive wealth of books on hunting and derring-do they produced is dwarfed by the literature of the post-World War I era.

Most of this literature is biographical or autobiographical in nature, or it examines some other subject of interest to hunters. There are even bibliographies on the subject, ranging from scholarly works such as treatments by this columnist dealing with Dr. David Livingstone, Sir Henry Morton Stanley, and Sir Harry H. Johnston to Ken Czech’s invaluable An Annotated Bibliography of African Big Game Hunting Books, 1785 to 1950.

Writers of considerable renown, such as Ernest Hemingway, Robert Ruark, Peter Capstick, and Wilbur Smith have titillated us with the romance of African sport in both fact and fiction. Anyone who reads outdoor magazines or delves very deeply into the literature of sport-hunting in Africa will recognize other authors such as Denis D. Lyell, Paul Belloni du Chaillu, “Pondoro” Taylor, “Karamojo” Bell, J. A. Hunter, H. A. Bryden, Sir Alfred Pease, Parker Gillmore, and Roualeyn Gordon-Cumming.

One side of African literature that has been largely overlooked is the contribution women have made to the field. While space in no way permits me more than the barest of overviews, I do want to mention some female writers on Africa, from yesterday and today, who greatly merit the attention of anyone interested in fine armchair adventure.

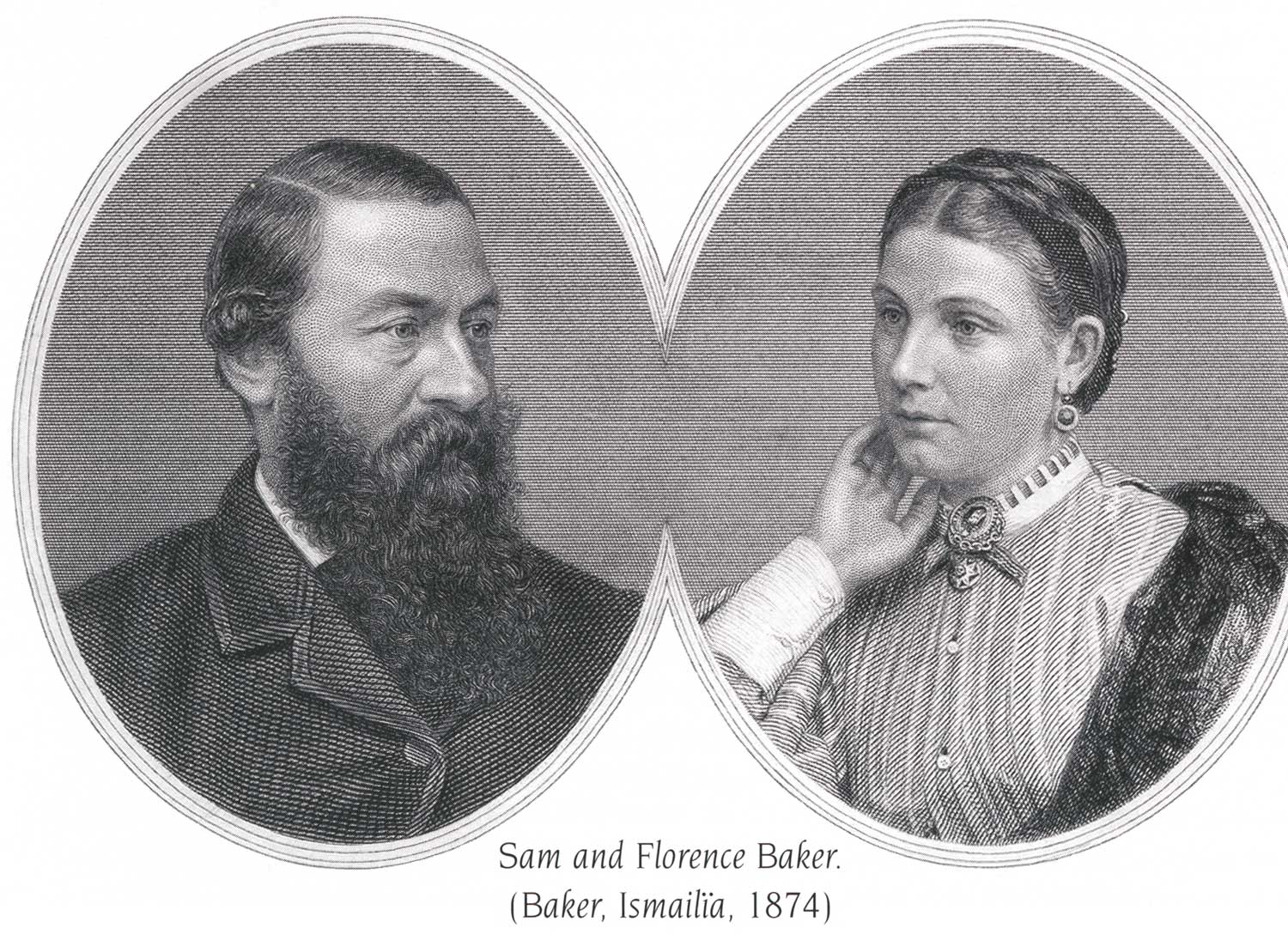

Among the earliest women to make a significant mark in Africa was Florence Baker, the mistress of Sir Samuel Baker. After buying Florence in a white slave market, Samuel proceeded to fall in love with and eventually marry her. She accompanied her famed hunter/explorer husband on his African trips and figures prominently in his books, The Albert N’yanza and Ismailia.

Intrepid to a fault, on more than one occasion Florence dealt with dangerous big game and even more dangerous natives when her husband was seriously ill. Her diaries from Africa were eventually turned into a most enjoyable book, Morning Star, edited by Anne Baker, the wife of distant relative of Sir Samuel.

The travels of two pioneering women in Africa, May French Sheldon and Mary Kingsley, trace back to the closing years of the 19th century. Sheldon, known as Bebe Bwana (“Lady Boss”) to the Masai in East Africa, came from an affluent and well-connected American family. Her parents were personal friends of famed explorer Henry Stanley, and it is likely he had some influence on her peripatetic propensities. Whether or not that was the case, by her early 20s she had achieved quite a reputation as a big game hunter in the Rockies, made four trips around the globe, and became one of the first female fellows of the Royal Geographical Society. Marriage in no way slowed her down, and in the early 1890s Sheldon undertook an extensive journey into the African interior, which resulted in one of the great classics of the late Victorian era, Sultan to Sultan. Even today, in reading its pages one has to be both charmed and amazed by her daring.

If anything, Mary Kingsley was even more daring. She certainly came from an adventurous and literary background. Her father, George Kingsley, was a widely traveled physician who accompanied Lord Dunraven on his noted sporting trip to the American West in 1870-75. Interestingly, Kingsley was fortunate to escape certain death thanks to adverse weather that had delayed his joining George Armstrong Custer’s expedition against the Sioux at Custer’s last stand. Mary also had two uncles, Charles and Henry Kingsley, who earned considerable renown as Victorian novelists.

The first 30 years of Mary’s life found her devoting much of her time to caring for her aging and ailing parents, but when they died in 1892, she gained the freedom and sufficient means to pursue her own interests. She wrote two books about her experiences, Travels in West Africa and West African Studies. Both books proved immensely popular, thanks in part to the fact that she wrote well, but also because a woman traveling alone in the African wilds was unheard of at the time. She would later die in South Africa while doing volunteer nursing work during the Boer War.

Mary Kingsley’s interests centered on ethnography and geography, but a near contemporary, Agnes Herbert, was a dedicated huntress. A well-educated woman of considerable means, Agnes and her cousin, Cecily, enjoyed hunting trips not only in Africa but to various remote corners of the globe.

Agnes recounts their experiences in Two Dianas in Somaliland and Two Dianas in Alaska, both of which are must reading for the lover of sporting history from the dawn of the 20th century. Agnes also wrote several other interesting books, including Casuals in the Caucasus: The Diary of a Sporting Holiday, The Life Story of a Lion, The Moose, and The Elephant.

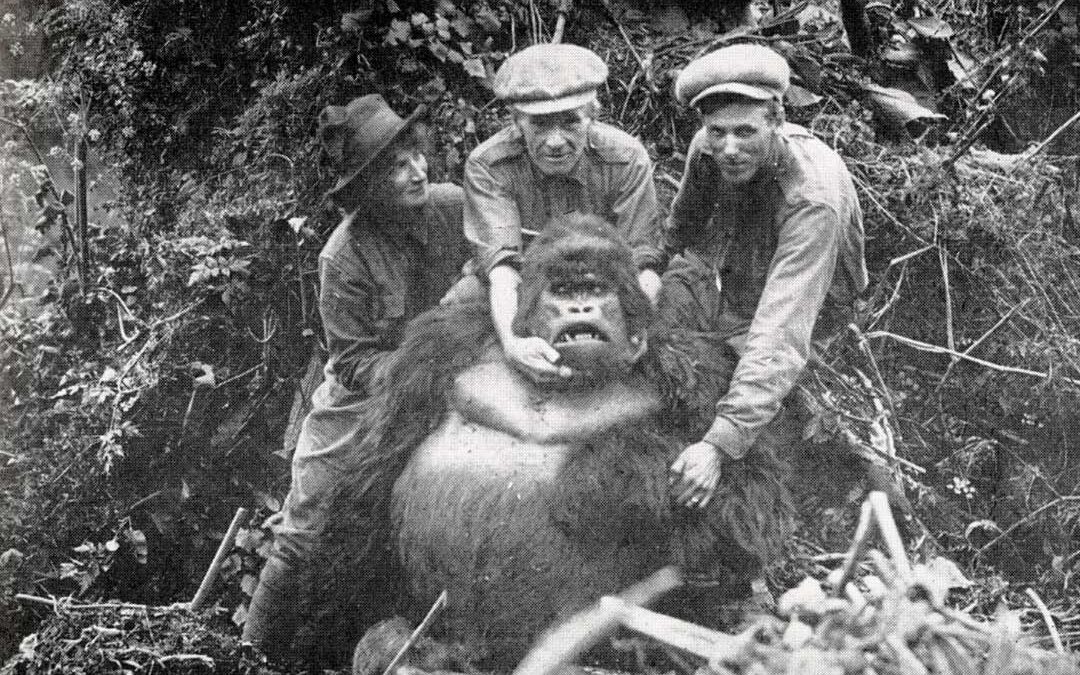

Another woman who pursued sport in Africa and elsewhere was Mary Hastings Bradley. Sometimes known as the “Tiger Lady,” she and her husband, Herbert, were financial supporters and participants in Carl Akeley’s 1921 expedition to the Belgian Congo to collect specimens for the American Museum of Natural History. Her account of the adventure is On the Gorilla Trail.

A few years later the Bradleys would return for a safari of their own that resulted in the publication of Caravans and Cannibals. The pair then hunted big cats in India and Indo-China, where she garnered the moniker “Tiger Lady.” Mary’s fine book Trailing the Tiger details their adventures.

There are other examples of ladies afield in Africa during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A pioneering treatment was Dorothy Middleton’s work from 1965, Victorian Lady Travellers. More recent, and certainly the two finest books on the subject, are Fiona Claire Capstick’s The Diana Files: The Huntress-Traveller Through History and Ken Czech’s With Rifle and Petticoat: Women as Big Game Hunters, 1880-1940.

As the subtitle suggests, Capstick’s scope is wide, both chronologically and geographically, and she provides general historical information as well as vignettes of individuals. As might be expected, though, she is particularly strong on her coverage of Africa.

Czech also builds on admirable research, but in a much narrower time frame. His primary focus is on Africa, although sport elsewhere is covered. Both books offer what in effect amounts to an extended guide to armchair adventure with the ladies through their ample bibliographical information.