Colorado Initiative Latest Effort to Manage Wildlife Through Public Opinion

In 1990, California voters passed Proposition 114 which banned mountain lion hunting in that state and set into motion scores of similar ballot measures across the country, usurping the authority of state wildlife agencies that are increasingly being subjected to the whims of public opinion. The ironic result of Prop 114 has been that more mountain lions are now killed each year in California than before the supposed ban was implemented.

The Sacramento Bee reports that an average of 98 mountain lions are killed annually under what are dubbed “depredation permits,” (issued by the state when mountain lions kill livestock and pets), which is nearly four times the number prior to the passage of the ballot initiative. The law of unintended consequences prevailed as it often does when emotionally charged wildlife management issues wind up on the ballot.

What is in question is whether wildlife should be managed by voters or the agencies whose mandate it is to do so. “States have wildlife departments run by professional biologists, researchers and other scientists,” says Jeff Crane of the Washington D.C.-based Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation. “The US has the most successful wildlife management model in the history of the world, and the core principle is that these professionals are entrusted to make the decisions for the benefit of both people and wildlife.”

Come November, Colorado residents will head to the polls to decide if Canadian gray wolves should be introduced to the state’s Western Slope. Initiative 114 made it to the ballot thanks largely to groups outside the state of Colorado. According to reports filed with the Colorado Secretary of State, more than 75 percent of the funding for the petition has come from out of state sources, including groups funded by George Soros, the billionaire liberal progressive who created the Open Society Foundations, which reports having a $19 billion endowment.

Despite biologists at the state’s own Parks & Wildlife Division recommending against an introduction of wolves, Governor Jared Polis has affirmed state law prohibiting agency staffers from publicly sharing opinions on ballot issues. His husband, 39-year old Marlon Reis, however, is a long-time vegan and outspoken animal rights activist who has weighed-in on the debate, supporting wolf introduction efforts in Colorado. In his Facebook posts, Reis quotes nearly verbatim from the faction supporting wolf introductions, “Rather than decimating elk herds as some feared they might,” he writes referencing wolf introductions in Yellowstone National Park, “these apex predators filled-in an ecosystem gap.”

That’s a gap, however, that many sportsmen feel they should be filling. “Hunters have provided the majority of conservation funding in this country for more than a generation,” says Ted Harvey, a former state senator and Campaign Director for Stop the Wolf PAC, a group leading the effort to oppose the wolf introduction initiative. “If their key argument for introducing wolves is that it will improve the health of the habitat by reducing elk and deer numbers, then allow hunters who pay expensive license fees and contribute mightily to the state’s rural economy to fulfill that role. Hunters can reduce herd numbers without wreaking havoc on livestock as wolves have done in Wyoming, Montana and Idaho where they were released decades ago.”

Roughly 350,000 big game hunting licenses are sold each year in Colorado and sportsmen contribute $1.8 billion annually to the state’s economy, according to a 2018 study commissioned by the Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) division. “Colorado is home to roughly 300,000 elk,” says retired CPW northwest regional manager Ron Velarde. “That’s more than any other western state by a considerable margin.”

And that’s what has many on the state’s Western Slope so concerned. Opponents to the introduction of wolves point to what’s already happened in Idaho, Wyoming and Montana to better understand what would happen should the wolves be brought in. “In Idaho, 35 wolves were initially introduced and that population now exceeds 1,500 animals,” writes former congressman and rancher Bob Beauprez in a Complete Colorado editorial. “The result has been devastating to backcountry big game outfitters. Half of them have gone out of business following the decline of elk numbers and the remaining 50 percent report a drop in business.”

A cow moose looks on as its calf falls prey to a wolf pack. Moose populations in Wyoming have declined dramatically since the introduction of wolves to that state. GETTY

What some see as a black and white issue has become a blue versus red debate, with densely populated Democratic urban centers imposing their will through the ballot box on rural, largely Republican counties.

“Activists in the greater Denver metroplex gathered the vast majority of required petition signatures to qualify the question for the ballot,” writes Beauprez. “Of course, they don’t want wolves released in their backyards. The drafters of the initiative made sure wolves would be foisted on the folks on the Western Slope.”

“That’s like asking someone in New York City if they’d prefer trash be dumped in their neighborhood or in New Jersey,” says Harvey. “When you see the slick ads from the wolf groups you wonder how we even survived without the wolves in the first place.”

One such group is called the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project (RMWP), a collection of mostly out of state environmental and animal rights organizations including the Sierra Club (embroiled in its own recent controversy over the racist views of its founder, John Muir), Defenders of Wildlife, and Natural Resources Defense Council among others. RMWP is not a non-profit organization, so the San Francisco-based Tides Center—backed by Soros—filed for non-profit status in Colorado on behalf of RMWP.

Visit the RMWP’s website and you’re greeted with commercials and videos that look like the sophisticated productions associated with lobby efforts of multi-billion dollar corporations rather than grassroots environmental groups. Leading their effort is longtime wolf advocate Mike Phillips, a former Yellowstone manager turned director of Ted Turner’s Endangered Species Fund. “What we did in Yellowstone could be done in Colorado,” says Phillips in one of several videos on the group’s site. “Our goal is to establish wolves from the high arctic to the Mexican border.”

“Unfortunately wolves are going to pay the price if that happens,” says Harvey. “The people in the areas where they would be released simply don’t want them and that leads to bad outcomes for the wolves. Talk to the people around Yellowstone and they don’t view the wolf introduction as a success. It’s about the federal government shoving bad policy down their throats from inside the Beltway.”

“Research demonstrates that after Colorado voters are presented with all of the facts, not just dubious claims by proponents,” says Mark Truax of Coloradans Protecting Wildlife, a group representing a coalition of farm, ranch, recreation and conservation organizations opposed to the wolf initiative, “they are no longer supportive of the introduction of wolves through the ballot box.”

Those views don’t show up on the RMWP website. Instead, you’re greeted with a man-on-the-street video asking random Denver passersby the simple question, “Are there wolves in Colorado?” Several of those queried answered in the affirmative, depicted as if they’re ignorant urbanites who wouldn’t have a clue about wolves. Then the voice on the video informs them that there are no wolves in Colorado, as if the notion of such is ridiculous unless the initiative allows the predators to be introduced in the state. Problem is, like several of the statements found on the RMWP website, the information is either false or misleading.

In February, CPW officials confirmed the presence of a pack of six wolves in northwest Colorado that had moved in from neighboring Wyoming. Numerous other wolf sightings, moreover, were reported prior to the agency’s announcement. Thus, as a headline in Denver’s 5280 magazine asked in its June 30 edition, “If Wolves Are Already in Colorado, Should We Still Reintroduce Them?”

Not if you ask the state’s ranching and outfitting community. Some 38 of Colorado’s 64 counties have adopted resolutions opposing the wolf initiative, and many of these are in rural areas where ranchers fear for their livestock should the wolves take hold and expand as they have in other states.

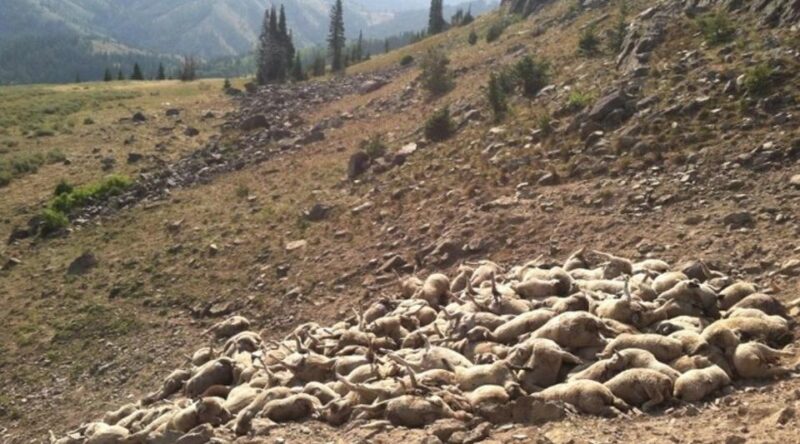

Idaho rancher, Jeff Siddoway, made national news when he reported losing 176 sheep in a single night as wolves chased his flock over a steep embankment, causing $28,000 in damages. Since wolves were introduced into that state in 1995, Idaho has confirmed that nearly 1,000 cattle, more than 3,000 sheep, 53 herd dogs, and horses, goats, mules and llamas have fallen prey to wolves—though the numbers are likely much higher as many attacks go unreported.

The remains of 176 sheep killed overnight when wolves ran them over a steep embankment, costing Idaho rancher Jeff Siddoway $28,000 in damages. COURTESY OF CINDY SIDDOWAY

None of these facts show up in RMWP materials. The site, instead, also goes further to proclaim emphatically that zero campers have been injured by wolves in National Parks. Not true, however, if you ask Matthew and Elisa Rispoli and their two young sons who were asleep in their tent in Banff National Park last August when a Canadian gray wolf tore through the tent, attacked the father and started to drag him away.

“It was like something out of a horror movie,” wrote Elisa in a Facebook post that was widely quoted by international media outlets. “I don’t think I’ll ever be able to properly describe the terror.”

RMWP also fails to mention that the Canadian gray wolf is a dramatically larger wolf than ever existed in Colorado. The Canadian subspecies can grow to more than six feet in length and weigh as much as 175-pounds according to Live Science, a sharp contrast to the much smaller 110-pound Great Plains wolf that roamed the state a generation ago. “These substantially larger wolves are dramatically more effective at killing elk and moose,” says Harvey. “This isn’t a reintroduction at all, it’s an introduction of an exotic, non-native species because no such animal ever existed in Colorado.”

“According to the Wyoming Game & Fish Department,” says Velarde, “before the first wolf introduction in 1997, the moose population numbered over 10,000 animals. Since then it has declined to fewer than 1,400 animals as recently as 2018. Most of this decline, according to that state’s biologists, can be attributed to the introduction of wolves to Wyoming.”

Canadian gray wolves are the largest wolves in the world, reaching upwards of 175-pounds. GETTY

The fact that Canadian gray wolves are known carriers of the deadly hydatid disease is yet another fact that didn’t make it to the RMWP website. This disease is caused by the tapeworm cyst Echinococcus granulosus. Humans can contract the disease when handling infected carcasses, from soil, dust and plants exposed to the cysts. According to a study reported in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases, “The tapeworm was detected in 39 of 63 wolves in Idaho and 38 of 60 wolves in Montana.”

For one Idaho nurse who contracted the disease when she and her husband moved from their Boise home to the mountains frequented by wolves, the disease was life altering. It often affects the liver, kidneys, lungs and brain, according to the World Health Organization.

“In 2001, I got sick and became confused,” says the woman who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal from pro-wolf groups. “It wasn’t until 2003 that I was diagnosed with hydatid disease. It’s a horrible affliction.”

According to the National Institutes of Health, hydatid disease has been the cause of at least 41 deaths between 1990 and 2007 across the U.S.

In 1859, John Stuart Mill in his book On Liberty, famously argued against the tyranny of the majority in what has endured as a cautionary tale to democracies the world over. When it comes to managing wildlife through the ballot box, it’s all about a public relations battle where facts often become the endangered species. Motivate the electorate through emotionally charged messaging—wildlife experts and science be damned—and you’re apt to have your way…for better or worse.

“I don’t believe in managing wildlife through the ballot,” says Velarde. “When you take management away from professional wildlife biologists you’re making a mistake…because there’s always unintended consequences.”

Just ask California.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow Sporting Classics TV host Chris Dorsey at Forbes.

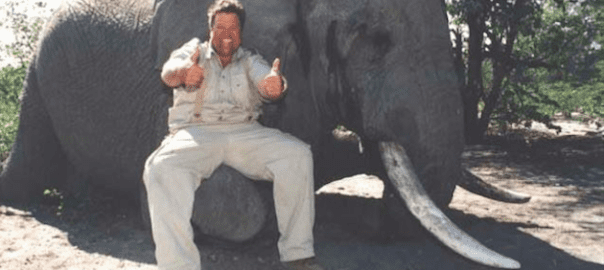

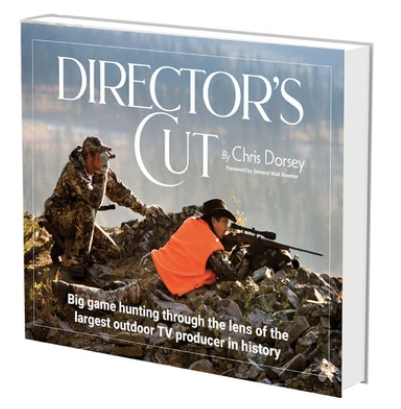

The World Of Sporting Literature Has A New Classic from one of the planet’s most widely traveled hunters. Director’s Cut…Big game hunting through the lens of the largest outdoor TV producer in history, is a book and film production more than 15 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of big game hunting.

The World Of Sporting Literature Has A New Classic from one of the planet’s most widely traveled hunters. Director’s Cut…Big game hunting through the lens of the largest outdoor TV producer in history, is a book and film production more than 15 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of big game hunting.

Dorsey has spent the past 25 years investigating and chronicling the animals, people and unforgettable places home to remarkable big game hunts while producing nearly 60 outdoor adventure television series. In the process, his teams amassed a library of more than 100,000 hours of HD footage and nearly 150,000 photographs, making Director’s Cut (the book and DVD) an unmatched celebration of the world of big game hunting. Buy Now