I know a sure cure for February cabin fever.

It’s just as well that February is the shortest month of the year. My grandfather used to maintain that it was so brief because it offered as large a dose of foul-weather misery as anyone could endure, and in many senses he was right. For the sportsman, February is a particularly difficult time. Autumn’s golden days have come and gone, and even fond memories of ducks turning upwind to decoys on a bitter December morning are fading away. Dreams of trout rising to a heavy hatch or a lordly turkey gobbler strutting deep in a hardwood slough seem impossibly distant.

But as the refrain from a hit song of yesteryear runs:

Down in Mexico it’s sunny;

Days are warm and sweet as honey.

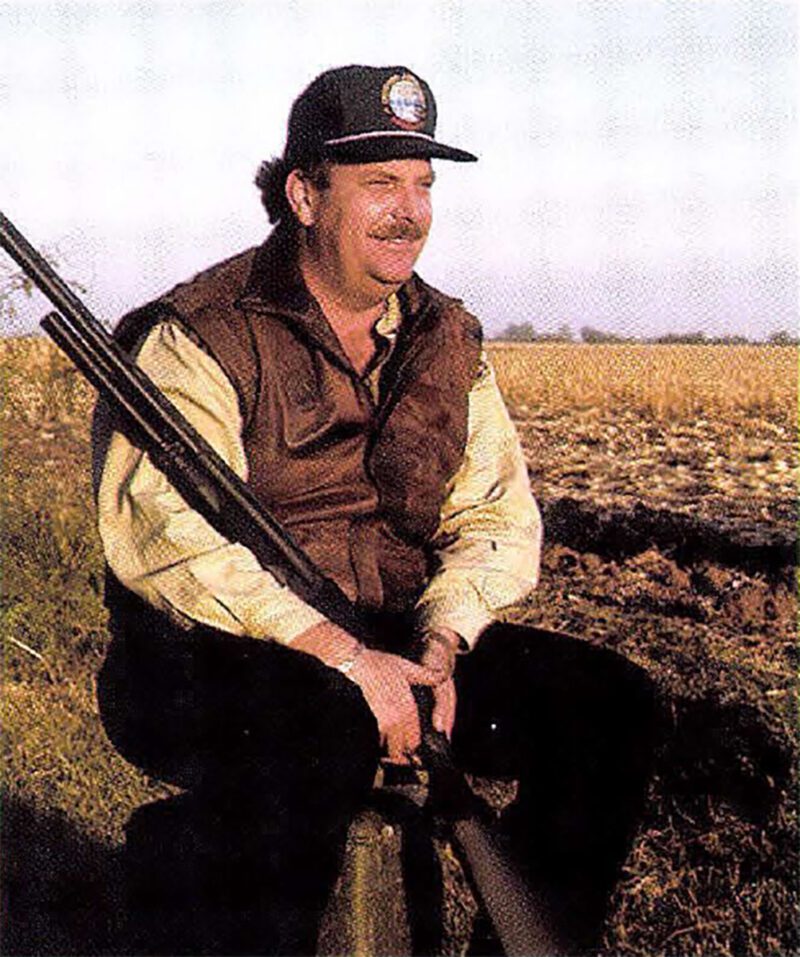

At least that’s what popped into my mind as I left a dreary, rain-sodden South Carolina for Ciudad Obregon in western Mexico. My friend John Cornett and I first flew to Phoenix where we met our host, Don Turner of Outdoor Adventures Worldwide. Fluent in Spanish and married to a native Mexican, Don runs hunts for doves, waterfowl and quail at his Las Palomas operation in eastern Mexico. Recently, he’s hooked up with Frank “Gabino” Ruiz in the Yaqui Valley of Sonora to extend his bird-hunting season and to offer some first-rate bassfishing on Lake Oviachic.

In Obregon, a modern city of some 300,000, we were greeted by Gabino, a congenial man who was educated in the United States and has extensive experience in the outfitting business. After settling into our rooms and eating a hearty meal, we loaded up for a trip to the dove fields. Irrigated croplands of wheat, cotton and sugar cane cover much of the region, and Gabino stays in touch with local farmers to pinpoint the birds’ movements.

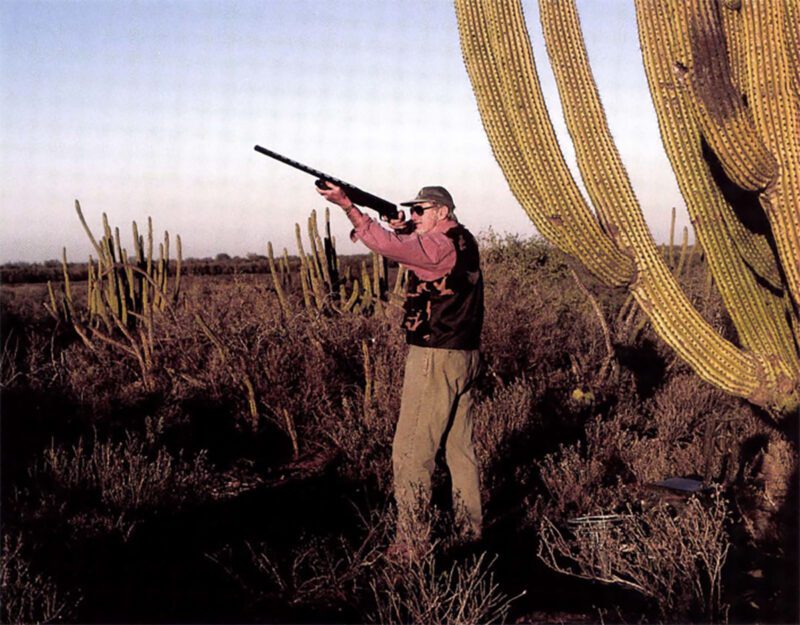

John Cornett pulls on a speedy mourning dove during late-afternoon shoot in a field laced with big saguaros. The fast-flying birds were challenging targets as they hurtled over and around the tall plants.

Our afternoon hunt was slow by Turner’s standards, but it would have delighted shooters back home. Small flocks of mourning doves dipped and twisted low over our field, while whitewings beat a steady pace overhead. Later in the day we watched flocks of ducks work a nearby waterway, a tantalizing harbinger of what awaited us in the morning.

Well before daylight we drove to the sprawling tidal marshes that fringe the Gulf of California. Gabino transports his hunters to the blinds in airboats. These amazing craft can traverse a half-dry sponge, and they enable Gabino to place hunters on shallow flats where no ordinary boat could venture.

Before sun-up, John and I were comfortably perched on dove stools in a slightly elevated blind (we didn’t even need waders). As the roar of the airboat faded into the distance, we heard a different roar — the wingbeats of a thousand or more ducks spooked off the water by the airboat. But the marsh quieted down quickly, and before long we found ourselves basking in the sound of rushing wings and ducks splashing into our spread.

Over the next two hours we enjoyed more shooting than one might reasonably expect in a season of duck hunting back home. Greenwings, bluewings and cinnamon teal zipped past our blind like over-sized bumblebees, and they were about as difficult to hit. John laughingly said the best way to shoot them was “see them coming in, turn immediately, and hope you’re quick enough to fire at them going away.” Other types of waterfowl were somewhat easier targets, especially the pichiguilas (fulvous tree ducks) which decoyed so well and so often that we renamed them Mexican dumb ducks.

Neither of us used calls, yet we killed our fair share of birds, including more than a half-dozen different species. Even more impressive was the bag of two other hunters in our group who took fourteen kinds of ducks, from big, fully plumed pintails to lesser scaup and redheads.

Once the shooting was over, John couldn’t wait to meetup with the other hunters for he had a story to tell — at my expense. While swinging on a bird that turned out to be a cormorant instead of a duck, I had managed to turnover my stool and tumble out of the blind (Is that a double whammy?). The only damage was to my pride, but John let everyone know what he thought about having to “retrieve” me from the water as if I were an over-sized duck.

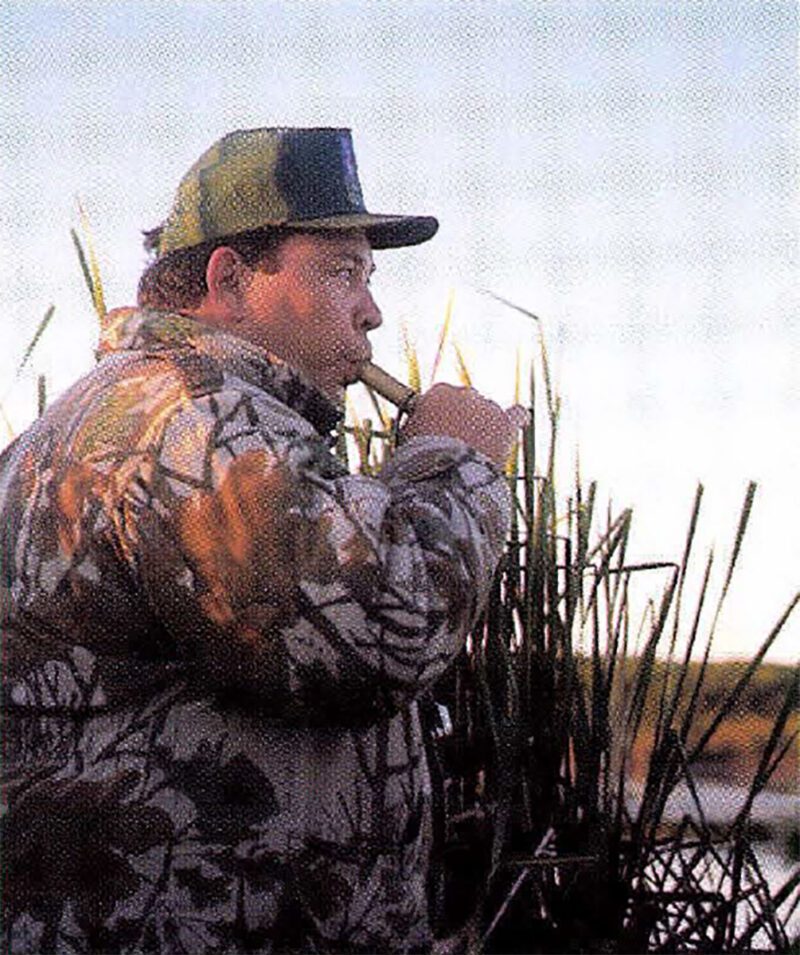

Frank “Gabino” Ruiz making some calls.

After lunch and a welcome siesta, it was off to the dove fields again, this time a large expanse of mesquite, cactus and brush situated between the birds’ roosts and nearby grain fields. Here we found some of the most furious bird-shooting I’ve ever experienced. Three or four flocks would fly within range at the same time, and I had to force myself to concentrate on one group of birds. On several occasions, even with my less than sterling abilities as a wingshot, I had to wait until my bird boy picked up the downed doves before I could resume shooting.

Within an hour or so I was nearing my limit of 30, and when Don came over to see how things were going, I was quite ready to get out my camera, take some photographs, and simply watch the others shoot. The targets were demanding, with wind-driven birds darting and careening among towering saguaros. It was the kind of shooting that has made Mexico such a great Destination for bird-shooters.

We finished up the day with a special treat. Don had a hankering for some fine cabrito, which is a specialty at a small restaurant in Obregon. I wasn’t sure young goat would be a choice dish, but the succulent meat was delicious and so tender that it fell from the bone.

The next day we turned to bass fishing at Lake Oviachic, an impoundment on the Yaqui River about a half-hour drive from the lodge. Several once-famous Mexican lakes became notorious for “short cycle” angling, with too much commercial netting, too many fishing camps and too little catch-and-release. But Gabino Ruiz hopes to avoid those pitfalls on Oviachic. He was instrumental in working with local and state authorities to begin bass stocking in 1990 and recently, in having Florida-strain largemouths introduced in the 32,000-acre reservoir. Bass in Oviachic can grow as much as two pounds a year, which says a lot for the lake’s trophy potential.

Six-pound-plus bass are now common in Oviachic, with the average size about three. In a day of hard fishing, a reasonably proficient angler can expect to boat anywhere from 25 to 50 fish.

In retrospect, John and I should have brought along a greater variety of lures, especially plastic worms and lizards, which proved far more productive than spinner-baits and crank-baits. This was somewhat surprising, since tilapia and thread fin shad are the basic forage fish for the bass. Still, we caught plenty of fish, almost all three pounds or larger. That same morning, Don Turner used artificial worms to land 25 largemouths in less than three hours.

Ruiz and his guides use airboats to whisk hunters to and from blinds on the vast shallow-water marshes along Mexico’s Gulf of California.

About the time we were winding up our second day of fishing, it dawned on us that the bass were staging on the rather sparse structure visible to the eye, mostly flooded mesquite. Had we concentrated solely on these stickups, we certainly would have caught more fish, and I should have said as much to our guide.

My stay in Mexico left me with three unforgettable memories. The first was an evening’s entertainment, which is standard for every group that stays at Yaqui Valley Hunting Lodge. After priming the pumps at an open and lavishly stocked bar, we sat down to a feast of Mexican dishes, as pleasing to the eye as they were to the palate. Then, a group of students from the local university sang and danced for us with a flair that explains why they have performed throughout the U.S. and in Europe.

The other two special moments came the following morning, when four of us — Gabino, Don, John and me — shared a large duck blind overlooking a vast tidal marsh. At sunrise Gabino began making music on his duck calls, and for the next two hours, flights of waterfowl were almost continuously within gun range. For once, everything clicked on my wingshooting, and even the devilishly difficult teal folded with satisfying regularity.

Perhaps even more gratifying, given the cavalier fashion in which John had recounted my humiliating tumble from the blind, was the fact that he proceeded to duplicate my performance. Admittedly, he was swinging on a duck instead of a cormorant, but when he fell over backwards he landed in gooey mud instead of water. As John scraped the muck from his gun and clothes, I couldn’t resist reminding him that he who laughs last, laughs loudest and longest.

Don Turner, owner of Outdoor Adventures, watches for doves at the edge of a grain field.

Good-natured bantering continued through the morning, and by the time the airboat picked us up, we not only had our allotted complement of ducks, we had developed the kind of camaraderie that comes from sharing wonderful moments afield.

The last of my wintertime blues had vanished. My outlook had brightened and life’s sometimes burdensome load seemed lighter. A few sunny days of Sonora sport had worked wonders, and I now know a sure cure for February’s cabin fever.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1996 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

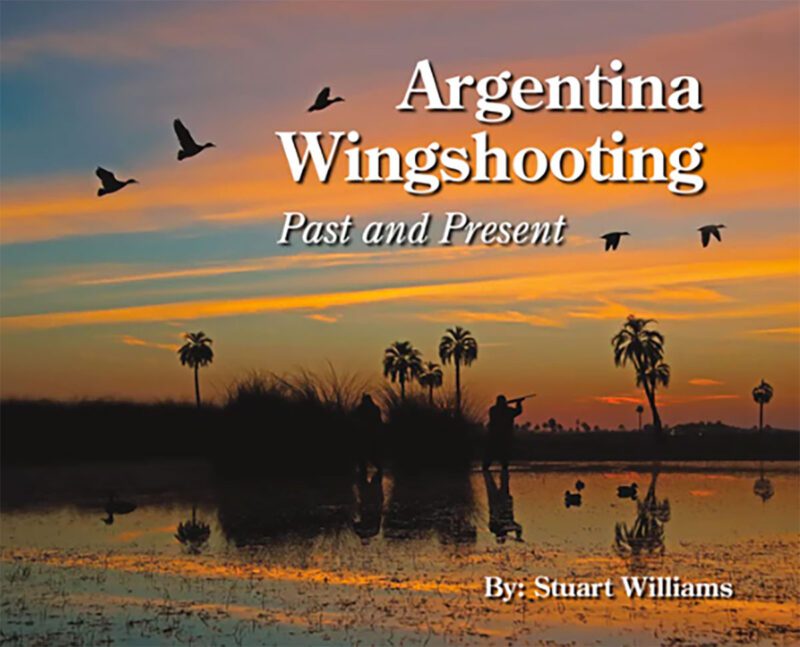

This lavishly illustrated book documents the best of Stuart Williams’ 40-year love affair with bird-hunting in Argentina. Stuart was preceded only by Hollywood actor Robert Taylor as one of hundreds of American sportsmen who have discovered the incredible, high-volume shooting for ducks and geese, doves and pigeons in the region surrounding Buenos Aires. Buy Now

This lavishly illustrated book documents the best of Stuart Williams’ 40-year love affair with bird-hunting in Argentina. Stuart was preceded only by Hollywood actor Robert Taylor as one of hundreds of American sportsmen who have discovered the incredible, high-volume shooting for ducks and geese, doves and pigeons in the region surrounding Buenos Aires. Buy Now