Even though Americans invented—among other things—the electric light bulb, the microwave oven and (for better or worse) personal computers, as far as I’m concerned, one of our country’s greatest achievements has been the perfection of the lever-action rifle. Yes, even more than the Kentucky rifle (also an American invention), which gave our colonial defenders extended range combined with accuracy, it was the lever action that gave frontiersmen the added benefit of multi-shot firepower. And while other companies, such as Marlin and Savage eventually entered the lever-action competition, it was Winchester that started it all.

“Sixty Shots Per Minute” boasted an 1862 broadside boldly touting Oliver Winchester’s “new” 1860 Henry Repeating Rifle, the first successful lever action to hit the market and obviously not taking into account the time required to reload the 15-shot rifle. The broadside further proclaimed, “A resolute man, armed with one of these Rifles, particularly if on horseback, CANNOT BE CAPTURED.”

That, unfortunately, proved not to be true, as evidenced by the fact that in 1867, a Union Pacific Railroad surveyor named Lanthrop Hills, while mounted on horseback and armed with his UPRR-issued Henry Rifle, was overtaken by a warring band of Indians and killed near what is now Cheyenne, Wyoming. Forty-six years later, Hill’s rifle–or what was left of it–was found by a retired Union Pacific employee; it is now on display in the Union Pacific’s museum in Council Bluffs, Iowa, as mute evidence of the important role this early lever action played in the building of the Transcontinental Railroad and the opening of the post-Civil War West.

This pre-’64 Winchester Model ’94 carbine is an ideal close-range deer and black bear gun, although these pre-’64 models have been escalating in value as collectables as well.

But the death of surveyor Hills notwithstanding, the Henry Rifle was far from perfect. For one thing, it loaded from the muzzle end, requiring the top of the magazine tube to be rotated so that the rimfire 44 Henry Flat cartridges could be slid down, making it necessary for the shooter to raise his body, thereby exposing himself to enemy fire. In addition, the cartridges were held against the follower (in order to cycle the action) by a spring-loaded brass tab, which traversed down along a slit in the underside of the magazine tube. When this tab reached the shooter’s supporting hand, the cartridges could no longer feed when the lever was cycled unless the hand was repositioned. This no doubt resulted in many a lost opportunity for rapid repeat shots when they were perhaps most needed and may very well have been the reason for Hill’s demise; when his Henry was found, it still had five cartridges remaining in the rusted magazine tube.

The Henry’s design flaws were overcome with the aptly-named Improved Henry Rifle of 1866. Winchester’s superintendent, Nelson King, had devised a loading gate that permitted cartridges to be inserted into the tubular magazine from the right side of the bronze receiver (a holdover from the original Henry’s receiver), and a wood forend solved the potential problem of a burnt hand from a heated barrel caused by rapid firing. Also, with Winchester’s reorganization of his company, the former New Haven Arms Company became the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, and the Improved Henry Rifle was rechristened as the first rifle to bear the Winchester name. Unfortunately, it was still saddled with the relatively anemic 44 Henry Flat cartridge, which was originally loaded with 13 grains of blackpowder. But even when boosted to 28 grains for the new Winchester, the copper-cased cartridge still only spat out its 200-grain 44-caliber bullet at a modest 1,125 feet per second (fps).

However, all of these shortcomings were overcome with the introduction of the Winchester New Model of 1873, as it was initially cataloged (but oddly enough, not until 1875, no doubt due to production and distribution difficulties), and which soon became known simply as the Winchester ’73. In turn, the Improved Henry Rifle was renamed the Winchester Model 1866–to differentiate the first Winchester from the second one–thereby setting the stage for naming all subsequent Winchester “Models” throughout the remainder of the 19th century.

Four different models were offered: a 24-inch barreled Sporting Rifle with checkered walnut pistol-grip stock; a 20-inch barreled Saddle Ring Carbine; and a full-stocked 30-inch barreled Military Musket. But more than simply a new name, the Winchester ’73–although still retaining the basic toggle-link action of its two lever-action predecessors–had a number of game-changing features going for it. First and foremost was the cartridge for which it was initially chambered–a new, proprietary bottle-necked, brass-cased 44-40 Winchester Center Fire (WCF), a centerfire cartridge that—unlike the rimfires that had come before it—could be reloaded. Consisting of a 200-grain soft lead, 44 caliber round-nosed bullet propelled by 40 grains of blackpowder, the resultant 1,310 feet per second (fps) soon proved itself to be more than adequate as both a man-stopper and for medium-sized game out to 100 yards; after that, the bullet dropped dramatically, along with a comparative loss in striking energy.

I remember years ago while small game hunting with a Winchester ’73 rife in 44-40, taking a shot at a crow that was approximately 100 yards away. At the sound of the shot, the crow took off and, by the time the bullet hit the dirt mound where he had been standing, only a puff of dust marked the spot. The crow was gone.

Later that same day, having learned my lesson about the 44-40’s slow-moving ballistics, I spotted another crow standing on a tree stump. This time I aimed a few inches over the crow and fired. At the sound of the shot, the crow took off, but this time he flew right into the path of the bullet.

In spite of the Winchester ’73’s ballistic limitations, it had a number of new features that added to its desirability among frontiersmen, ranchers and sportsmen, including an iron receiver (changed to steel in 1884) with removable sideplates and a sliding dust cover to shield the action from the elements. Consequently, with the Saddle Ring Carbine and Sporting Rifle leading the way in sales, the Winchester ’73 was destined for immortality, as evidenced by the fact that in 1878, Colt began chambering its popular Single Action Army (SAA) revolver in 44-40, making it a natural to pair with the Winchester ’73. In response, in 1880 Winchester introduced a 38-40 chambering for its Model ’73 along with a 32-20 cartridge in 1882, making the Winchester ’73 and the SAA even more compatible.

The popularity of the Winchester ’73 with the shooting public is evidenced by the fact that it remained cataloged until 1920, with a total of 720,610 guns being built within that 47-year timespan—enough to continue keeping the Winchester 1873 on gun dealers’ shelves until as late as 1924. In addition, the purported “Gun That Won The West” (a sobriquet attributed to Winchester’s Edwin Pugsley in 1919) got an added boost in popularity in 1950 when Universal Studios released its motion picture, “Winchester 73,” starring James Stewart and co-starring a prop department mockup of a Winchester 1873 “One of One Thousand”—a special order gun—along with a lesser-produced “One of One Hundred” that was part of a misguided 1875 Winchester promotion suggesting that some guns (sold at a premium) were more accurate than others.

But as good as it was, the Winchester ’73 had one major drawback: its action was too short to chamber any of the popular big game hunting cartridges of the day, including the then-new 45-70 Government. Thus, Winchester Repeating Arms was losing out on the lucrative sportsman’s market, as outdoorsmen in pursuit of elk, moose and bison were opting for harder-hitting single shots, such as those made by Sharps and Remington.

To remedy that situation, and no doubt to keep its lever-action reputation intact, Winchester simply beefed up its already existing Model 1873, lengthening and strengthening the receiver, barrel, forend and stock, thereby enlarging the entire gun. Although the toggle-link action still was unable to negotiate the length of the popular 45-70 cartridge, Winchester did the next best thing: developed a proprietary 45-75 round that, while not quite as long as the 45-70 (thanks to a squatter 350-grain bullet) packed a bit more punch due to its slightly larger powder charge. I was able to experience that firsthand when I took my original Winchester ’76 on a wild boar hunt and dropped a hefty tusker with a single shot. Later chamberings were in 45-60 and 50-95 Express in 1879, and 40-60 in 1884.

Dubbed the Winchester Model 1876, this new rifle was unveiled as part of Winchester’s display at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition where it, appropriately enough, became known as The Centennial Rifle. Available as a fully-stocked Carbine and Musket, a Sporting Rifle and half-magazine Express Rifle were also offered. Not surprisingly, Winchester’s new big game rifle was enthusiastically accepted by America’s hunters and the Express Rifle in particular found fame and game in places such as India and Africa, as well.

One of the most notable admirers of the Winchester 1876 was Theodore Roosevelt, who, during his 1880s ranching days in Dakota Territory, ordered two of them–a half-magazine Sporting Rifle and a custom-stocked Carbine–both in 40-60 caliber and elaborately factory engraved by John Ulrich.

The Browning-designed twin locking lugs of the Winchester ’86 made the action strong enough to transition from blackpowder to smokeless, as shown here on a Winchester 71—a 1935 “modernized” version of the Winchester 1886.

Indeed, at the time Winchester was offering a number of factory options, including engraving, gold, silver or nickel plating and fancy wood. But that wasn’t enough to stave off competition. When Marlin came out with its first lever action, the Model 1881 chambered in 45-70 (among others), Winchester was motivated to take action. For the solution to its marketing dilemma, Winchester turned to the Browning brothers of Ogden, Utah,—Matthew and John—who had previously come to the company’s aid with their Model 1885 single shot. Now they were tasked with creating a lever-action repeater capable of handling a variety of big game cartridges, including the popular 45-70 Government.

The solution that John Browning came up with was a complete departure from anything Winchester had done before. Rather than retain the older toggle link system, Browning’s new rifle was more akin to Browning’s falling block 1885 single shot. For this new Winchester, however, John Browning redesigned the action and incorporated twin vertical locking bars that slid up on either side of the receiver and firmly anchored the sliding bolt when the lever was closed. Working the action proved to be as smooth as warm butter, with everything locking up as solid as a bank vault. Produced in Rifle, Carbine and Musket configurations, and eventually chambered in everything from 40-82 to 50-100 (including of course, the coveted 45-70) the new Winchester Model 1886 ended up being one of the most popular mid-range big game hunting rifles of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The author dropped this 6-point bull elk with a single shot from his Miroku reissue of the Winchester 1886 Extra Light in 45-70, using a Buffalo Bore 500 grain FMJ bullet.

I discovered my first Winchester 1886 rifle at a gun show back in the 1960s, where it sat on a dealer’s table in relative obscurity due to the fact that it had very little finish left (although its markings were still sharp), plus its magazine tube was slightly dented and it was chambered for the obsolete (even back then) 38-56 WCF. With a little haggling, I ended up buying that octagon-barreled ’86 (which I later learned was made in 1890) for $60 and promptly took it to the no-longer-existing King’s Gun Works on Olympic Boulevard in Los Angeles to have the dent removed. I then had no less an expert gunsmith than P.O. Ackley rebore the barrel to 45-70. Using Remington 405 grain factory ammo, I found that the Winchester ’86 now printed 1 1/2 inch groups at 100 yards. Switching to Federal 300-grain hollowpoints, I have lost count of the number of deer and wild boar I have taken with that hefty rifle, although I have since switched back to lead bullets to preserve Ackley’s expertly-cut rifling in the barrel’s relatively soft steel.

It is worth noting that due to its robust configuration, the Winchester 1886 had no trouble switching over into the era of smokeless powder, being reconfigured as a half-magazine 1886 Extra Light Weight in 1896 and then easily vaulting the turn-of-the-century fence and landing well into the first part of the 20th century. Even then, it wasn’t discontinued but updated in 1935 with coil springs instead of flat and solely chambered for the proprietary 348 Winchester as the Model 71, where it remained in production for another 23 years.

Advances in modern ammunition have given more versatility to today’s lever actions, such as this Browning ’86 Extra Light in 45-70.

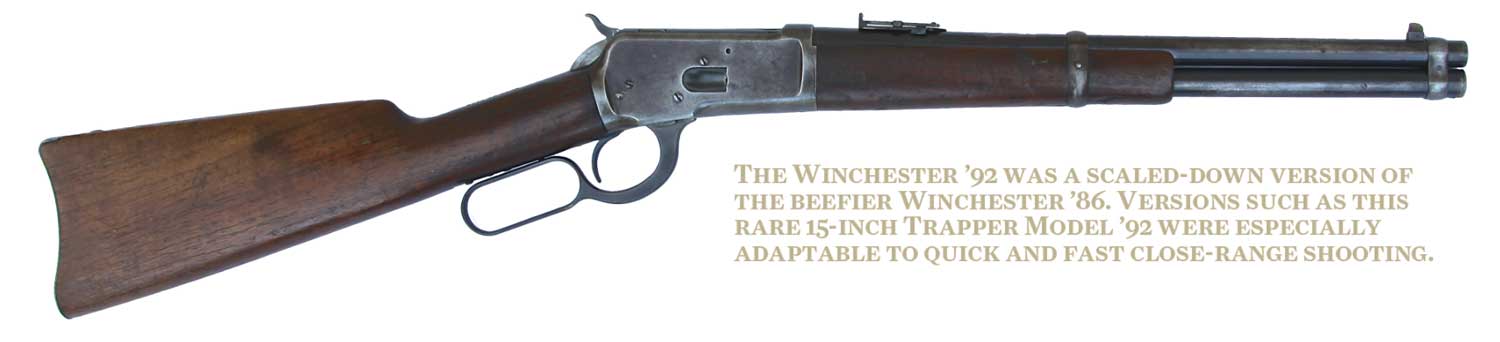

Obviously, the Model 1886, like everything John Browning designed, was over-engineered, so it was easy to simply scale the gun down a bit to produce its “little brother” successor, the Winchester 1892, which featured the same twin bolt locking lugs and butter-smooth action, but was chambered for the frontier’s “holy trinity” of cartridges, 32-20, 38-40 and 44-40, thus competing, in a way, with Winchester’s earlier Model 1873. However, as the Model 92 had a much stronger action, in 1903 a Winchester High Velocity 44-40 factory load was brought out, but was discontinued right after World War II due to the ongoing inability of some people to comprehend the warning on the boxes that stated these hotter loads should not be used in Winchester ’73 rifles or vintage single action revolvers. Many a gun–and unfortunately a few shooters’ extremities–were damaged because of this oversight. By contrast, during the 1960s and early ’70s (before Browning came out with its B-92 replica by Miroku in 1979), I recall a number of Winchesters ’92s being rechambered to 44 Magnum.

While the Winchester 92 proved to be popular among horsemen, hunters and ranchers, especially in its carbine format, it was soon dramatically overshadowed by yet another lever action–also a Browning design—the now-immortal Winchester 1894, the first repeating rifle and carbine (the only two basic configurations Winchester initially made) to be adapted for smokeless powder cartridges. Ironically, however, at the time of its introduction in 1894, production difficulties with the new nickel steel barrels relegated the very first Model ’94s to be chambered for two older blackpowder chamberings, the 32-40 and the 38-55. It wasn’t until a year later when the Model ’94 finally came out in the two much-touted 25-35 and 30 WCF smokeless powder chamberings, the latter of which has become more popularly known as the 30-30.

Although the Winchester ’94 is thought of as the ideal deer rifle, Hacker has found that his pre-’64 30-30 works equally as well on wild boar.

Winchester Repeating Firearms paid Browning $15,000–the same amount he had previously received for his Model 1886 and 1892 patents–for rights to manufacture the Model ’94. The Winchester ’94, however, utilized an entirely different internal mechanism, consisting of a single, solid steel bar that slid up and locked behind the closed bolt, thus providing greater safety to the shooter, an important selling point in those transition years between blackpowder and smokeless. Also unique to the Model ’94 was its hinged floorplate that pivoted down when the action was opened. In addition, the slightly larger trigger guard could readily accommodate gloved hands and, as a result, it was the rifle and carbine of choice during the 1897 Alaskan Gold Rush, causing the Winchester ’94 to be christened, “The Klondike Model” during its early years.

In addition to becoming an extremely popular “working” ranch gun, the Model ’94 carbine was adopted by numerous law enforcement agencies, including the Los Angeles and Glendale California Police Departments, various railroad police agencies and such diverse organizations as the Texas Rangers and New York State Troopers. And during World Wars I and II approximately 1,800 special ordinance-marked Model ’94 carbines were issued to U.S. troops stationed along the Mexican and Canadian borders, as well as to some home guard units and members of the Army Signal Corps. It has also become one of the most popular deer rifles ever carried afield by American hunters. In more recent years, the Winchester ’94 has also held the distinction of becoming one of the most plentiful commemorative rifles ever produced by any firearms company.

But just as the Winchester ’94 heralded in the age of smokeless powder, it also saw the beginning of the use of spitzer bullets, which–unhindered by concerns of bullets accidently igniting the cartridges in front of them in a magazine tube during recoil—offered greater trajectory benefits to bolt-action shooters. In response, John Browning once again came to Winchester’s rescue with another design departure from the past, by introducing the Winchester 1895. Instead of an under-barrel tubular magazine, the Model ’95 featured an internal four-round fixed box magazine that permitted round-nosed (instead of flat) and spitzer ammunition. And instead of a side loading gate, the Winchester ’95 was loaded by opening the lever, which retracted the bolt, and pressing each cartridge into the gun, base-end first.

Produced in Carbine, Sporting Rifle and Musket configurations, the Model ’95 saw use with United States Army volunteer units during the Spanish American War, which was where Theodore Roosevelt first encountered the gun and eventually became one of its biggest promoters, taking it, after his two-term U.S. Presidency, on his African safari of 1909-1910, where he called it his “Big Medicine” gun. Subsequently, the Winchester ’95 also became a favorite of both the Arizona and Texas rangers, as well as prominent sportsmen such as author Zane Grey. It’s not surprising such luminaries would prefer this gun, for the Winchester ’95 was expensive to manufacture; in 1918, when the Model ’94 carbine sold for $25.50, a Model 1895 Sporting Rifle cost $38–a substantial difference in those years. Produced in chamberings that included 30-40 Krag, 303 British, 35 Winchester, 405 Winchester and 30-06 Springfield, there were 425,825 Model ’95s made until 1935, when it was finally discontinued. Interestingly, more than half of these were chambered in 7.62x54mmR and were sold to the Russian government–the largest military order Winchester ever had.

World War I introduced American doughboys—many of whom were raised with Winchester lever actions—to bolt action Springfields and Mausers, thus entering the “modern” 20th century era of hunting rifles. But even with the ongoing proliferation of factory and custom-made bolt actions that continues today, the Winchester lever action has continued to remain far from obsolete. Sporterized versions of the 19th century guns that were updated in the 1930s (such as the Model 1886 becoming the Model 71 and the Model ’94 being offered as a Model 55) continued to keep the original lever actions alive and shooting. The Winchester 88 was another attempt to bring the lever gun into a more updated format. And today, made under the Winchester banner by Miroku of Japan, the Winchester Models ’66, ’73, ’92, ’86, ’95 and 71 continue to be sold to an appreciative and enthusiastic audience of shooters and collectors.

Today’s lever actions have come a long way since their 19th century introduction, as evidenced by the Henry Big Boy X, introduced in 2012 as that company’s first centerfire rifle.

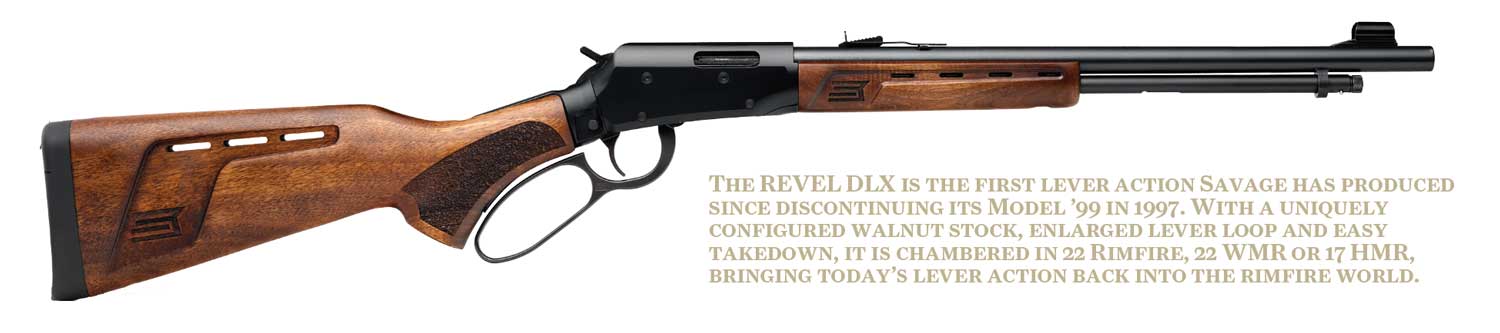

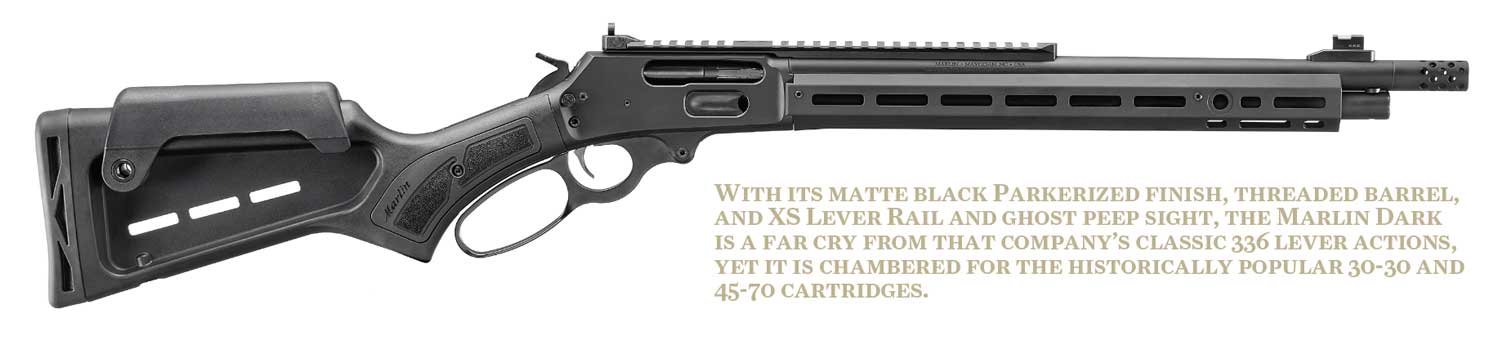

Moreover, beginning in the late 1960s, the Winchester lever action began venturing into the realm of Italian-made replicas. And relatively recently, it has been dramatically–and I might add, sometimes almost unrecognizably–adapted into various configurations of modern sporting arms. This is evidenced by guns such as the Henry Repeating Arms Lever Action Supreme with its internal (concealed) hammer and which feeds from a detachable five-, ten- or multi-round AR-15-style magazine; Ruger’s Star Wars-style-stocked Dark Series Models 1895, 336 and 1894 with threaded muzzle brake barrels, Picatinny rails and skeletonized “Cheek Riser” buttstocks; and Smith & Wesson’s Model 1854 Series featuring–among other things–XS Ghost Ring rear sights and a removable magazine tube for reloading. Even Savage Arms, which once produced its rotary magazine Model 99 as a competitor to Winchester’s Model ’94, now has a new wide-levered Revel DLX with a skeletonized-stock and chambered in 22 Long Rifle, a caliber also echoed by Winchester’s new aluminum-framed lightweight 22 Rimfire Ranger, a Model ’94 look-alike.

Whether it’s 19th century originals, 20th century classics or 21st century innovations, after three centuries of existence, it looks like Oliver Winchester’s lever-action concept is here to stay.

The Winchester Model 94 and its revolutionary 30-30 cartridge changed the world of shooting forever. Sam Fadala is here to tell you the whole story, tracing the development of the most popular hunting rifle ever designed, discussing sights, ammunition, and cleaning procedures, as well as telling you how to hunt large and small game. Although a little dated, current authors don’t write like their predecessors. Sam Fadala remains one of the best. Good information for the serious collector and shooter. Shop Now

The Winchester Model 94 and its revolutionary 30-30 cartridge changed the world of shooting forever. Sam Fadala is here to tell you the whole story, tracing the development of the most popular hunting rifle ever designed, discussing sights, ammunition, and cleaning procedures, as well as telling you how to hunt large and small game. Although a little dated, current authors don’t write like their predecessors. Sam Fadala remains one of the best. Good information for the serious collector and shooter. Shop Now