William R. Leigh ranks with Russell and Remington as one of the great eyewitness artists of the Old West. But his finest works may be of wildlife and sporting subjects.

William Robinson Leigh was nearly 40 years old when he traveled to the Southwest in 1906. Disgusted and nearly destitute after ten years of trying to make a living painting in New York, he had accepted the invitation of a former classmate, Albert Groll, to visit him at Laguna, New Mexico. The Sante Fe Railroad made a good bargain when it gave him free passage in exchange for a future picture. In the American West, Leigh found inspiration for the art that would bring him enormous fame, primarily as a painter of western subjects, but also as the gifted creator of wildlife and sporting art.

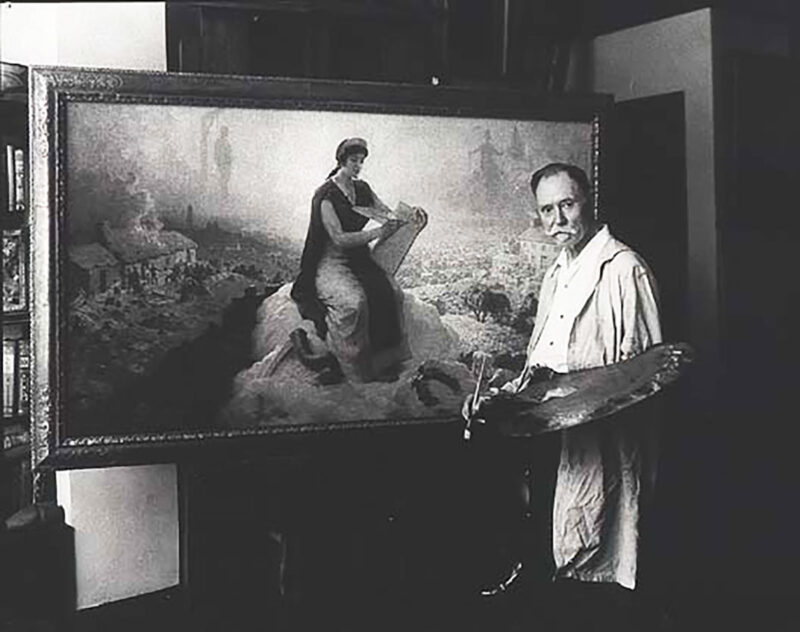

William R. Leigh in 1939, at age 73.

Stepping off the train at Laguna, Leigh knew he had come to the right place; the desert landscape, sagebrush, pastel-colored mesas, and adobe pueblos were everything he had imagined and more. “I was eager to waste no time whatever, “he wrote many years later in an unpublished biography. “I saw that I needed studies of everything: the vegetation, the rocks, the plains, sky, the Indians and their dwellings … So far as possible I must be a sponge, soak up everything I saw.”

At Acoma, which he described as “wildly picturesque and weirdly dramatic … like a fantastic dream, ” Leigh painted countless Indian studies and made sketches of the Enchanted Mesa across the valley. About Zuni he wrote: “Here was the town, the people, whom Coronado had known. This was the town which had been reported to be paved and roofed with gold. The people made wonderful pottery and jewelry.”

By winter his cash had run out and he went back to New York and illustrating, but in future years Leigh returned more than two dozen times to the Southwest. Fascinated by the Indians’ primitive day-to-day existence, he became a student of Navajo, Hopi and Zuni cultures. In all, he painted more-than 150 Indian canvases, some of them as large as 6 1/2 x10 1/2 feet. (The only good Indian in art, he once said, was a big Indian.)

In the summer of 1910, Leigh added big game hunting tohis western experiences. When Albert Groll told him that taxidermist Will Richard in Cody, Wyoming, was looking for a field artist to accompany him on a hunting trip in the Grand Tetons, Leigh jumped at the chance. This time out, Richard and Leigh camped several weeks on the banks of mountain trout streams southwest of Cody, and Leigh took back 30 sketches of mountain scenery and animals. On future trips with Richard, Leigh both hunted and painted, once bagging a mountain sheep and another time a trophy elk.

Buffalo Mother, an enchanting 36 x 48 oil, is among many Leigh paintings and drawings at the

Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

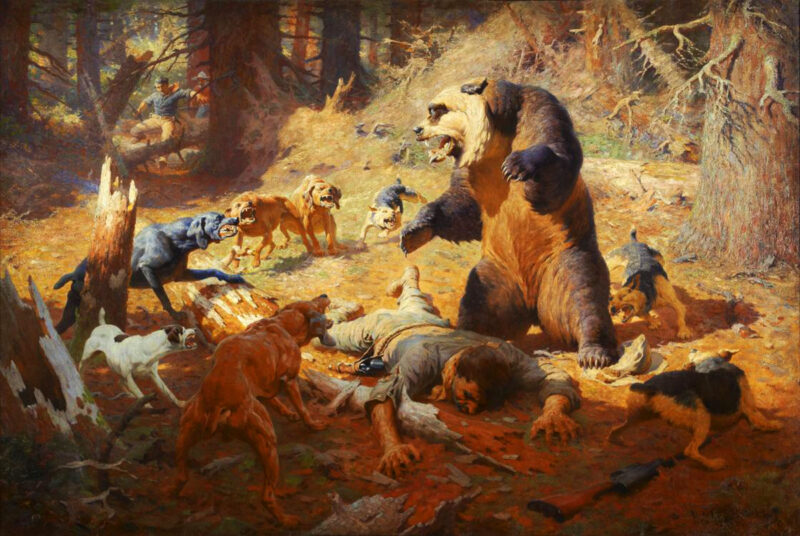

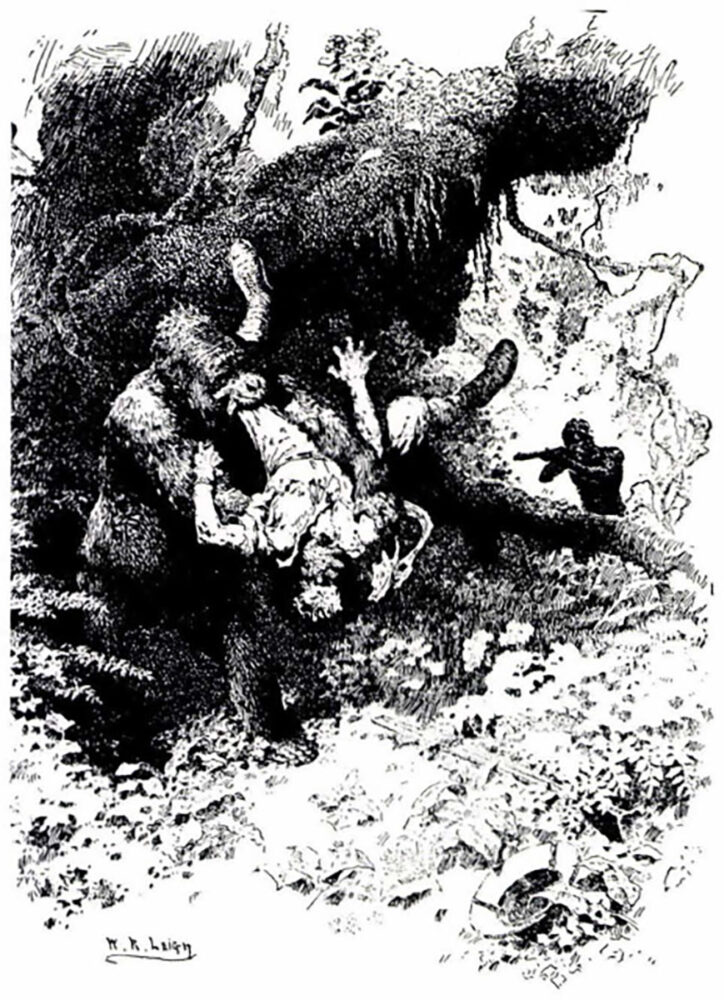

Two years later in 1912, Will’s brother, Fred Richard, guided the bear hunt that Leigh immortalized in Grizzly At Bay, one of the most famous hunting paintings in American art. The trip was sponsored by J. D. Figgins, director of the Museum of Natural History in Denver, who wanted a grizzly for a habitat group. Leigh went along as a field artist. Figgins later told a reporter for the Denver Rocky Mountain News that once the dogs had cornered the bear on the slope of a mountain, Leigh asked him to hold off killing it until he’d made some sketches and photographed it:

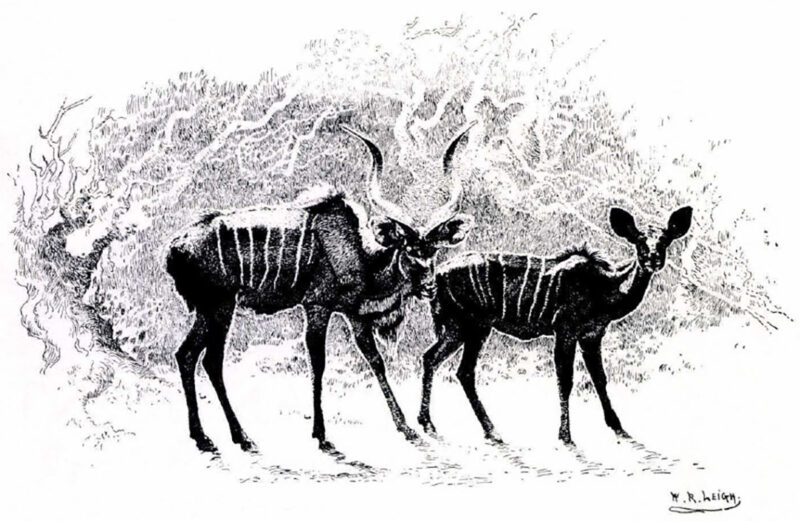

Greater Koodoo and other sketches of African wildlife appear in Leigh’s best-selling book, Frontiers of Enchantment.

“Leigh got to work with his Kodaks and pencils and we waited nearby, changing our position occasionally in order to maintain a vantage point in case the bear should make a break for liberty. It was in one of these maneuvers, I think, that the guide came too close to the fighting dogs and was knocked down. This gave Mr. Leigh the idea which he has incorporated in his picture as it was finished — the spectacle of one of the hunters lying prone under the bruin.”

William R. Leigh went unappreciated for most of his lifetime. Some of the blame can be laid to his difficult personality; he was crusty and opinionated, noted for his lack of tact. Modern art made him want to throw up, and he said so frequently. “Any vulgar fool could create a masterpiece in abstraction,” he told an audience, and modern art “disfigured the wall on which it hung.” He also took on big business and organized religion, both of which he said exploited people. One of his most sensational paintings, The Reckoning, protests capitalism; it portrays an unscrupulous, middle-aged businessman surrounded by grasping and accusing hands of all ages, one of them the hand of death.

Art critics took pot shots at Leigh’s work for years, often unfairly, he thought. Judging from their complaints about too many sunsets or too many fat ponies, Indian papooses and the like, their objections usually concerned his subject matter. No one ever questioned his superb draftsmanship. In the end, W.R. Leigh lived to see himself hailed as “the last of the great Russell-Remington-Leigh triumvirate.” By the late1940s, his mural-size paintings were selling for $15,000.

A Close Call is one of the most famous hunting scenes in American art.

William Robinson Leigh was born at Maidstone, his family’s Georgian brick plantation home in Berkeley County, West Virginia, on September 23, 1866. Unfortunately, his timing was inopportune. His parents, William and Mary Colston Leigh had abandoned Maidstone with the onset of the Civil War, Mary taking her four older sons to live with relatives in Virginia, and her husband enlisting in the Confederate Army. When they returned in1865, Maidstone was in shambles.

Leigh remembered the postwar years as “a ghastly, long drawn-out torture.” His father couldn’t make a go of farming without slaves, and the family eventually lost its property. In better times, his older brothers had been tutored by private teachers, but Willie was taught at home by his mother. Lacking the advantages enjoyed by his siblings, and taunted by them and their playmates, he withdrew into himself, developing an inferiority complex and paranoia. No doubt he was also affected by the harsh beatings inflicted by his father.

Growing up wary of people, Leigh developed a passion for animals. At Maidstone, he amused himself by drawing portraits of farm animals, including horses, cows and dogs. Their habits became second nature to him: “I don’t know when I learned that a horse must be mounted on the left side, and a cow milked on the right; it seems to me I always knew these things.” When he was six years old, Willie took first prize at the Martinsburg County Fair with a paper cutout of an elephant chasing a man on horseback.

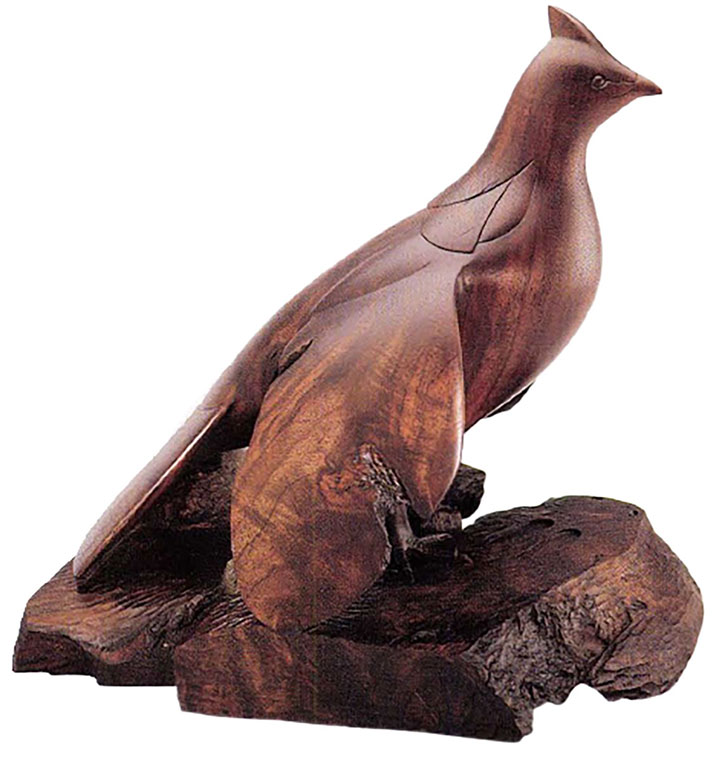

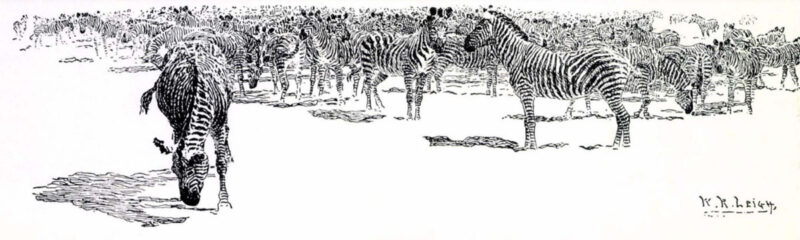

Above all else, Leigh prided himself as a “master animal

draftsman,” whether it be zebras or wild horses.

His artistic talent impressed his mother but no one else in his family. “My grandfather thought that painting was an occupation fit only for a woman, unworthy of men,” he recalled. “In those days I was tolerated — A fool with a faculty. It was discussed at length in my presence; I was a freak. The faculty was for drawing.”

Fortunately, Mary saw to it that he receive some training. When Leigh was 14, she put him on a train for Baltimore where he studied drawing with Hugh Newell at the Maryland Institute of Art and lived with her sister and husband. At the end of his first term, his high marks prompted a Baltimore collector, William Wilson Corcoran, to give him $200 to continue his studies. After three years, he had made such brilliant progress that Newell recommended that he study abroad.

Seen off by his parents, young Leigh sailed for Germany in 1883, shortly before his 17th birthday. Once admitted to the Royal Academy in Munich, he remained there until he was 30. Mary had talked two of his uncles into paying his expenses, and Leigh studied intently, becoming an expert draftsman, but he put off entering painting school for several years. “When one begins to paint before he can draw well,” he wrote home, “he finds the difficulties so increased that he is crushed and is at a loss to know how to advance.”

The Leader’s Downfall, 7 x 10 ft oil.

His uncles were anxious for him to finish his education, but Leigh wouldn’t commit himself to a schedule. Explaining this to his mother, he wrote: “Do not think that all I have to do is to go into the Antique one year, Nature one year, Paint one year and Composition school one year, and then come home an artist. I might as well tell you now, that it will take much, much longer than you think … I have begun the study of art now and there is no turning back.”

His uncles withdrew their support once he became 21, but Leigh stayed on in Germany by painting on giant panoramas and cycloramas, then popular in Europe, and selling an occasional painting. When he returned to America in 1896 after 12 years of rigorous training in the Munich tradition (characterized by exacting draftsmanship and vigorous brushwork, with genre themes the preferred subject matter), he had every hope of establishing his reputation as a leading American painter.

Once again his timing was off; collectors at the turn of the century were ignoring American painters in favor of the French Post-impressionists. Leigh wanted to produce a truly native art depicting the American West, and he tried but failed to find a patron who would pay him 100 a month in return for his entire output. The reality was that making a living as an American genre artist was not easy. For the next ten years, selling an occasional portrait or genre painting on the side, W. R. Leigh drew illustrations for magazines, mainly Scribner’s.

Encounters between man and beast, some of them depicting violent situations, appear in many Leigh drawings. This is a sketch of Buffalo Hunt.

After being hospitalized for a lengthy illness (possibly tuberculosis and probably aggravated by depression), Leigh married a young nurse, Anna Seng, in 1899. According to their only child, William Colston Leigh, his mother was one of the original Gibson Girls. The couple was divorced four years later, and Leigh mentioned her only briefly in his autobiography, saying that “it was not due to any fault of mine that the marriage failed.” When Leigh went west in the summer of 1906, he was leaving both personal and professional problems behind.

In 1913, Leigh began exhibiting his western paintings with the Snedecor and Babcock Gallery in New York, which represented numerous American western artists including Charlie Russell, Frank Tenney Johnson, E. L. Blumenschein and Herbert Dunton. Unfortunately, his genius went unrecognized. His paintings were too photographic, the critics pointed out; one wrote that “his viewpoint is frankly that of the illustrator, intent upon depicting natural phenomena and the incidents of life.” This same year, Leigh also applied and was turned down for membership in the National Academy of Design; it angered him deeply when the Academy hung the Plains Indian painting he submitted above a door.

Leigh continued exhibiting and sometimes sold a painting, but things went from bad to worse with the start of World War I. The American art market virtually dried up, and in Leigh’s words, “illustrating was all shot to hell” because the magazines were using photographs. For a time he considered abandoning art, but after auditioning unsuccessfully for stage and screen, he thought better of the idea. To pay for a painting trip to Arizona in 1916, he joined the scene-painters union and painted backdrops.

But from this low point, his fortunes steadily improved. By the war’s end, Americans were taking a fresh look at their western heritage, and Leigh began receiving popular and critical acclaim. His paintings were included in major exhibits and were also appearing in newspapers and magazines across the country. Between 1913 and 1926, more than 150 of his paintings were reviewed in the New York journals and most of them drew high praise.

Nearing his 55th birthday, Leigh surprised his friends by marrying fashion designer Ethel Traphagen in 1921. The two had met in Arizona eight years earlier, when Ethel was researching Indian costumes for Ladies Home Journal. Leigh had known immediately that he wanted to marry her. Ethel was 16 years younger, and she had no intention whatsoever of becoming a housewife, but once they worked out the details, their marriage was a great success.

Mountain Sheep Hunters, oil, 1912. This and other paintings on these pages appear in W.R. Leigh, a full-color biography featuring more than 100 of his most prominent works.

After a camping honeymoon in the West and Southwest, the pair returned to New York — and their separate apartments. Ethel believed it imperative that they retain their individuality, and her notion worked. They made a good team; Leigh helped Ethel develop the Traphagen School of Fashion and Design in New York City, and Ethel publicized Leigh’s paintings in her new magazine, Fashion Digest. She also became his best press agent, promoting his work vigorously for the rest of his life. Much of Leigh’s recognition can be traced to Ethel.

In 1926, at 60, Leigh embarked on the greatest adventure of his life. Asked by Carl Akeley to sign on as a field artist with the American Museum of Natural History in New York, he accompanied Akeley’s final expedition to Africa. Carl Akeley had raised taxidermy to an art, pioneering the use of sculpted forms on which the skins were fitted. His new African Hall would be the finest exhibit of its kind in the world.

Mountain gorillas held a special fascination for Leigh.

This drawing is based on a native’s tale of an enraged gorilla that tore an English hunter “limb from limb.”

Akeley planned to collect specimens for ten habitat groups, among them, greater kudu, water hole, African buffalo, elephant and gorilla. The expedition sailed in February, reaching Nairobi in late March. Leigh’s job was to sketch and photograph scenes that he would later paint as diorama backgrounds. Savoring every moment, he often went to great lengths — sometimes jeopardizing his personal safety — to get his reference. On one occasion, the artist and his native guide followed a buffalo trail deep within a swamp. Marsh vegetation formed thick, ten-foot walls on each side of the trail, reducing visibility to several feet. Leigh was almost certain they would blunder into an enraged buffalo, but before long, they entered a large amphitheater where he found and sketched the “trampled and tormented vegetation” he needed for his habitat painting. Later, after Leigh related his story back at camp, Akeley muttered:

“You’re a God-damn fool!”

Leigh wrote about this and other experiences in his best-selling book, Frontiers of Enchantment (1938, Simon and Schuster, New York). He called Africa “an unexampled storehouse, a marvelous virgin reservoir of incomparable inspiration for painters … the world’s most sublime theater for romance and adventure.” It was a time and place he wanted to preserve: “Doomed all too soon to be a vanished world, Africa needs artists more than she needs the historian and the scientists.”

In his book, which features dozens of captivating pen-and-ink drawings, Leigh reveals a keen sense of observation in a text that is skillfully and thoughtfully written. After several days in the rugged forest habitat of mountain gorillas, he wrote: “Fantastically ugly, when first sighted in his native haunts the gorilla gives the impression of unreality; of being some monstrous apparition conjured up by the imagination, wildly and appallingly hideous.”

The man-ape arouses in you a psychological reaction no other animal produces. You know he is not a man, yet you feel that he is not a beast in the same sense that other animals are. Strange fancies race through your brain. Is this what we all looked like a million years ago? Those irresistible feelings of fascinated terror, as you gaze at him, arise from no conscious train of thought: they are purely emotional, but none the less gripping, inescapable and spring from the humanistic actions and attributes of the gorilla, as well as from his appearance. For not only does he look like a gnomish man — he acts like one.”

It was in gorilla country, 14,000 miles above sea level in the Congo, that Carl Akeley died of typhoid and exhaustion on November 17, 1926. Leigh mourned his loss and sat up through much of that night with Akeley’s body. “It was a dreary experience, sitting in the dead of night on this lonely mountain amid primeval savagery and thinking of the career cut short — realizing that a great man lay dead. He had given his life to pursuing a magnificent idea.”

Taking Ethel with him, Leigh returned to Africa in 1928 with the Carlisle-Clark expedition to collect specimens and sketches for a lion group. Following the stock market crash the next year, work on the African Hall came to a standstill; when it resumed in 1932, Leigh painted the mammoth background murals, assisted by a battery of young artists. Akeley had told Leigh he wanted the most accurate and artistic backdrops possible, and Leigh’s paintings are masterworks. Several of them were featured in a Life magazine article, published after the African Hall opened in 1936.

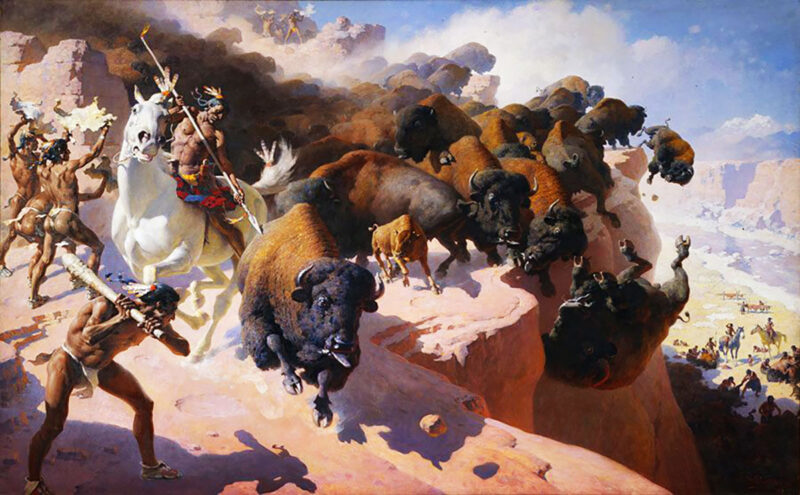

Buffalo Drive by William Robinson Lee.

By now Leigh was in his 70s, but just beginning to hit his stride as a painter. After a 37, OOO-mile around-the-world jaunt with Ethel, he returned to the Southwest, gathering stiIl more sketches for future paintings. He devoted the rest of his life to easel and mural painting, and his output was astonishing. In one, three-year period beginning when he was 82, he produced 79 paintings. Having become a public figure, he was also a sought-after speaker, noted for his outspoken views.

In 1950 the Maryland Institute, where Leigh had studied as a youth, mounted his largest exhibition; it contained 184 paintings, among them Buffalo Drive, The Buffalo Hunt, and The Leader’s Downfall (depicting Plains Indians taking out the lead horse in a pack of wild mustangs with lassos), each of them 6 1/2 x 10 1/2 feet. Dr. Edward Weyer, editor of Natural History Magazine cited The Buffalo Hunt as one of the most remarkable animal paintings in art history.

A portrait of the artist in his studio.

The final five years of his life brought honor upon honor, and Leigh relished every one of them. Among them was his election to the National Academy of Design, although the long-awaited honor came only days before his death.

In the September, 1954 issue of the Journal of Living, Leigh was quoted as saying: “The world is so wonderful, so marvelous. If people would only open their eyes to it. If only they would truly see the color and enchantment waiting to be discovered right before them.”

Perhaps he had these thoughts in mind on March 11,1955, as he worked on a painting of the sun going down behind the Organ Mountains in New Mexico, where he andEthel had camped on their honeymoon. After several hours of painting, Leigh decided to take a nap; he never woke up.

Writing in Fashion Digest, Ethel said: “Of recent years he worked in his quiet studio on New York’s Fifty-Seventh Street and let his brush roam the windy plains — among the land, the life and the people he helped preserve for America.”

Finishing the final book in the iconic Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers is the epitome of Sir John Seerey-Lester’s spirit. Filled with over 120 paintings and 45 descriptive chapters, the new 200-page book relives the compelling stories of 25 acclaimed hunters and explorers.

Finishing the final book in the iconic Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers is the epitome of Sir John Seerey-Lester’s spirit. Filled with over 120 paintings and 45 descriptive chapters, the new 200-page book relives the compelling stories of 25 acclaimed hunters and explorers.

Amid his fight against cancer, Sir John Seerey-Lester was working tirelessly on his final book of the Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers, when he passed away in May of 2020. He is survived by his wife and fellow artist, Suzie Seerey-Lester, who carries his torch with vigor and pride. Buy Now