Though engaging as a literary craftsman, Harris is even more appealing as an artist.

The game-rich veld of southern Africa was his studio; lions, elephants, and even a now extinct species of wild horse were his subjects. Although he would spend less than a year hunting in the Dark Continent, he was able to combine his talents as author and artist to produce two extraordinary books. As one student of his life has written, ” few men could have packed more adventure into a comparatively short life” than this remarkable individual, William Cornwallis Harris.

The game-rich veld of southern Africa was his studio; lions, elephants, and even a now extinct species of wild horse were his subjects. Although he would spend less than a year hunting in the Dark Continent, he was able to combine his talents as author and artist to produce two extraordinary books. As one student of his life has written, ” few men could have packed more adventure into a comparatively short life” than this remarkable individual, William Cornwallis Harris.

Except for those with a special interest in Africana and the literature of big game hunting, few sportsmen have heard of Harris, despite a number of striking similarities between his career and that of John James Audubon. Both were first-rate field naturalists and self-taught artists who devoted countless hours to observing the species they painted. They were even active during the same time frame. Harris explored Africa’s unknown hinterland ,paintbrush and palette in hand, in the late 1830s — precisely when Audubon was completing his famed Birds of America. Indeed, in 1838, the year in which Audubon’s seminal study first appeared, Harris published his Narrative of an Expedition in South Africa, which in later editions became Wild Sports of Southern Africa. That book’s success was a prelude to the appearance, two years later, of Portraits of the Game and Wild Animals of Southern Africa, a magnificent volume that would immortalize Africa’s big game species just as Audubon’s work focused worldwide attention on American birds.

Penniless, both Harris and Audubon turned to wealthy British subscribers to fund their books which, over the century and one-half since they first appeared, have experienced common fates. Today, intact copies of each book have become exceedingly rare, largely because their exquisite, hand-colored plates have been plundered by art collectors.

Yet for all these similarities in their works and careers, a singular difference separates Audubon and Harris as surely as the Atlantic Ocean separated their respective fields of endeavor. Audubon’s name has become a household word among lovers of nature and art, while Harris has languished in obscurity. Unquestionably, the man and his work, both artistic and literary, deserve much more.

William Cornwallis Harris was bornin Kent, England in 1807. Following preparation at a military school, he became an engineer in the Indian Army. At his headquarters in Bombay, he served in various military capacities, eventually achieving the rank of major.

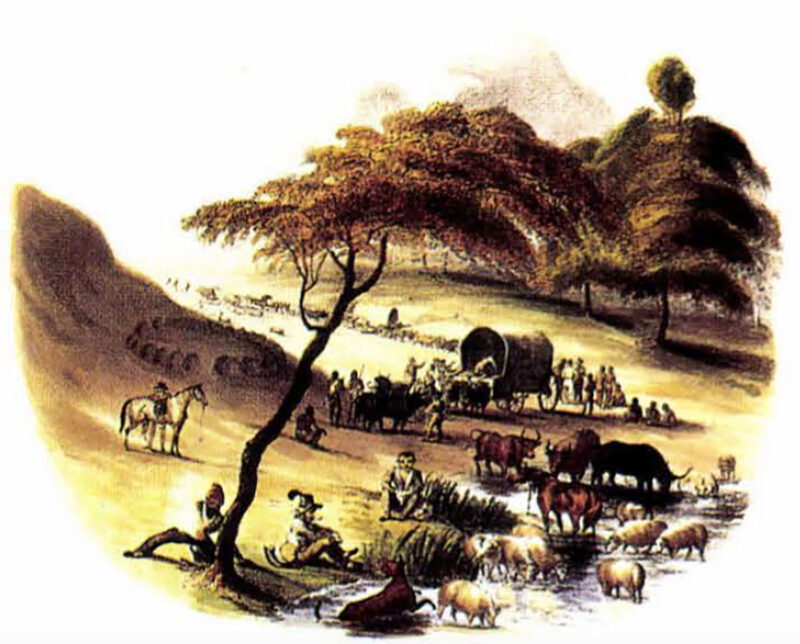

Harris’ career in the Indian Army was one of distinction, yet it was his exposure to Africa that placed fame within his grasp. In 1836 he sailed to the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, where he hoped to recover from a recurring, life-threatening illness. Once in South Africa, Harris was soon well enough to plan an extended hunting trip to the interior. He was determined, in his own candid words, to indulge in “shooting madness.” This affliction, if that is the proper description, had been one of his outstanding characteristics from “boyhood upwards.” He was in no sense ashamed of his passion for hunting. Instead, he introspectively analyzed it as being “the most delightful mania I have ever found.” Harris had the rare good fortune to pursue this “mania” in the virgin wilderness of Africa.

Harris’ career in the Indian Army was one of distinction, yet it was his exposure to Africa that placed fame within his grasp. In 1836 he sailed to the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, where he hoped to recover from a recurring, life-threatening illness. Once in South Africa, Harris was soon well enough to plan an extended hunting trip to the interior. He was determined, in his own candid words, to indulge in “shooting madness.” This affliction, if that is the proper description, had been one of his outstanding characteristics from “boyhood upwards.” He was in no sense ashamed of his passion for hunting. Instead, he introspectively analyzed it as being “the most delightful mania I have ever found.” Harris had the rare good fortune to pursue this “mania” in the virgin wilderness of Africa.

Perhaps the best way to appreciate what unfolded before Harris is to join him in the pages of The Wild Sports of Southern Africa.

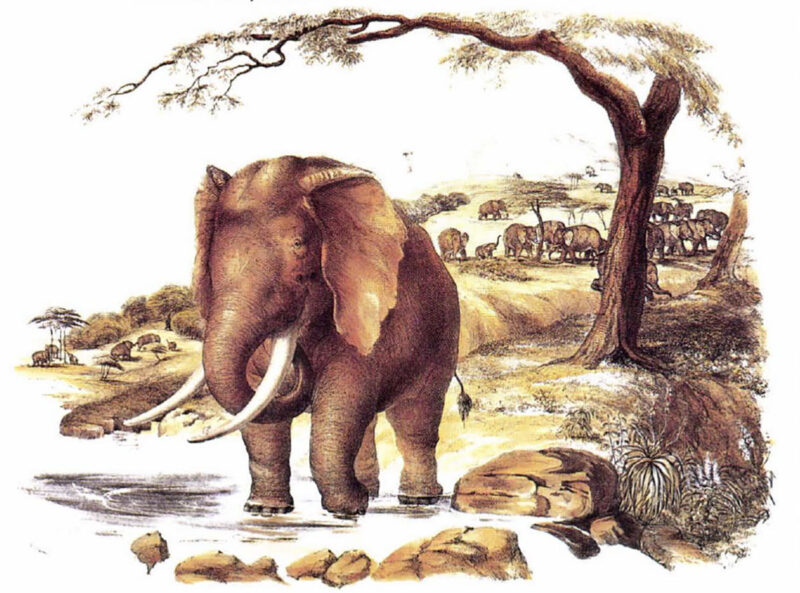

“To the sportsman, the most thrilling passage in my adventures is now to be recounted. In my own breast, it awakens a renewal of past impressions, more lively than any written description can render intelligible; and far abler pens than mine, dipped in more glowing tints, would still fall short of the reality, and leave much to be supplied by the imagination. Three hundred gigantic elephants, browsing in majestic tranquility amidst the wild magnificence of an African landscape and a wide stretching plain, darkened far as the eye can reach, with a moving phalanx of gnoos and quaggas, whose numbers literally baffle computation, are sights but rarely to be witnessed; but who amongst our brother Nimrods shall hear of riding familiarly by the side of a troop of colossal giraffes, and not feel his spirit stirred within him? He that would leave the haunts of man, and dive, as we did, into pathless wilds, traversed only by the brute creation — into wide wastes, where the grim lion prowls, monarch of all he surveys, and where the gaunt hyaena and wild dog fearlessly pursue their prey.”

With passages of this sort dotting its pages, Wild Sports attracted wide readership and launched an ongoing exodus of intrepid European sportsmen to South Africa. As Harris had discovered (and subsequently shared with others), there was “something truly soul-stirring and romantic in wandering among the free-born denizens of the desert.”

With passages of this sort dotting its pages, Wild Sports attracted wide readership and launched an ongoing exodus of intrepid European sportsmen to South Africa. As Harris had discovered (and subsequently shared with others), there was “something truly soul-stirring and romantic in wandering among the free-born denizens of the desert.”

Harris took an almost military approach to his sport — at times his descriptions read like battlefield operations. After approaching a large herd of springbok, he fired “both barrels of my rifle into the retreating phalanx, leaving the ground strewed with the slain. Still unsatisfied, [I]could not resist the temptation of mixing with the fugitives, loading and firing, until my jaded horse suddenly exhibited symptoms of distress.”

There is no denying that many of his passages grate on today’s conservation conscience. In Wild Sports he boasts of having “slain the king of beasts in every stage from whelphood to imbecility.” Yet we must not forget the time and place of his “campaign.” When one observes, in Harris’s words, “the herd before me increasing from hundreds to thousands, and reinforcements still pouring in from all directions,” thinking in terms of conservation becomes virtually impossible.

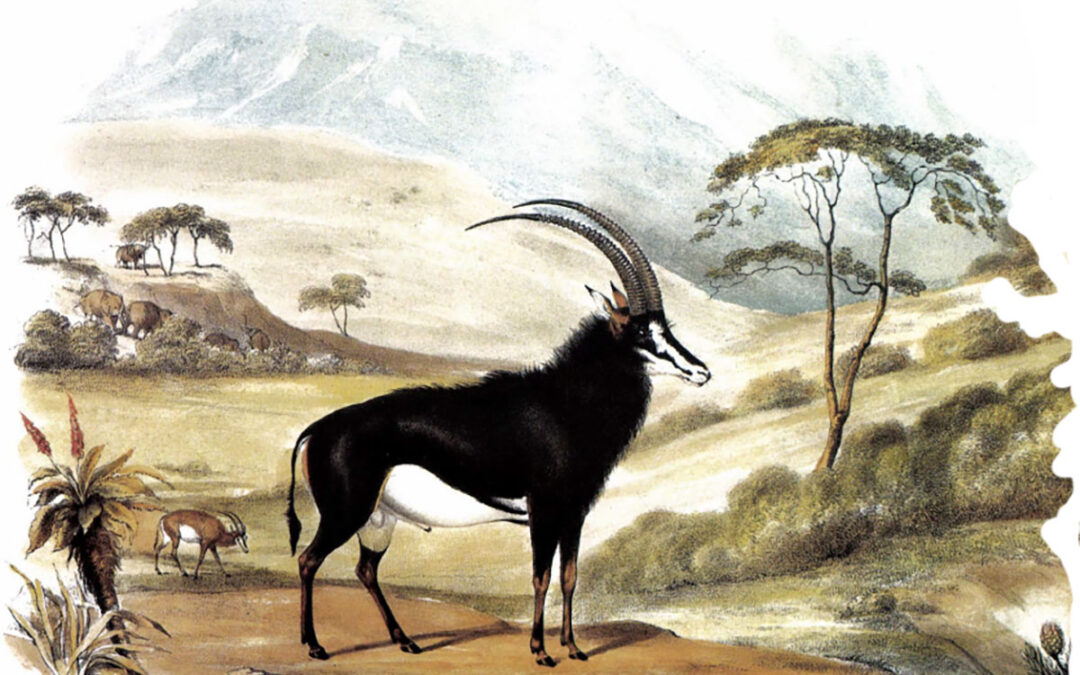

It would be grossly unfair to judge Harris from a modern perspective; besides there was much about the man that was attractive. It is pure delight to join him, after a long day afield, in “nocturnal bivouacs” where “joyous fires sent forth their cheering influence in various parts of our gipsy camp.” Similarly, the reader experiences an involuntary surge of adrenaline when the author kills his first “Harris Buck.” Awed by the animal ‘s exquisite beauty, he predicts that his discovery will “doubtless become the admiration of the world.” Harris, it seems, was right on target, for the sable antelope, with its long scimitar horns and jet-black hide, has become one of the most popular of all African trophies.

It would be grossly unfair to judge Harris from a modern perspective; besides there was much about the man that was attractive. It is pure delight to join him, after a long day afield, in “nocturnal bivouacs” where “joyous fires sent forth their cheering influence in various parts of our gipsy camp.” Similarly, the reader experiences an involuntary surge of adrenaline when the author kills his first “Harris Buck.” Awed by the animal ‘s exquisite beauty, he predicts that his discovery will “doubtless become the admiration of the world.” Harris, it seems, was right on target, for the sable antelope, with its long scimitar horns and jet-black hide, has become one of the most popular of all African trophies.

Harris repeatedly found himself overwhelmed by the “emotions which the excitement of African wild sports naturally produce.” He gloried in a “life of adventure,” adding that ” its very privations” were “peculiarly adapted to my humour.”

A contemporary reviewer praised Harris’ books because “they transport Southern Africa, with its landscape, its animals and its skies, into our drawing rooms and libraries.” Many others were captivated by his descriptions of the vast, untamed veld. In fact, almost every great hunter of the late 19th century — Baldwin, Baker, Bryden, Selous and others — credits Harris with first directing his attention to African sport.

Though engaging as a literary craftsman, Harris is even more appealing as an artist. He admittedly lacked the talents of other Victorian painters such as Thomas Baines and Joseph Wolf, who specialized in African scenes, yet he was a fine draftsman with an excellent feel for color. Harris sketched and painted with the same intensity that was the hallmark of his hunting, and he was “determined to bring back correct delineations” of Africa’s big game. “I never moved without drawing materials in my hunting-cap, and during brief cessations from hostilities, I found ample employment for the pencil instead of the rifle.” The end result was a glorious visual glimpse of South Africa’s natural wonders.

In his Introduction to Portraits, Harris sums up what he accomplished artistically:

“With the design, if possible, of supplying some measure of this palpable defect in our Zoological galleries, the portraits contained in the present series were originally undertaken. How manifold soever their imperfections, if viewed as productions of art, they can boast of being adorned with the beauties of truth, having all been delineated from living subjects, roaming in pristine independence over their native soil. My predilection for sylvan sport has afforded me all the opportunities…of waxing intimate with the dapple denizens of the grove to an extent which abler artists and more finished zoologists have been denied.”

“With the design, if possible, of supplying some measure of this palpable defect in our Zoological galleries, the portraits contained in the present series were originally undertaken. How manifold soever their imperfections, if viewed as productions of art, they can boast of being adorned with the beauties of truth, having all been delineated from living subjects, roaming in pristine independence over their native soil. My predilection for sylvan sport has afforded me all the opportunities…of waxing intimate with the dapple denizens of the grove to an extent which abler artists and more finished zoologists have been denied.”

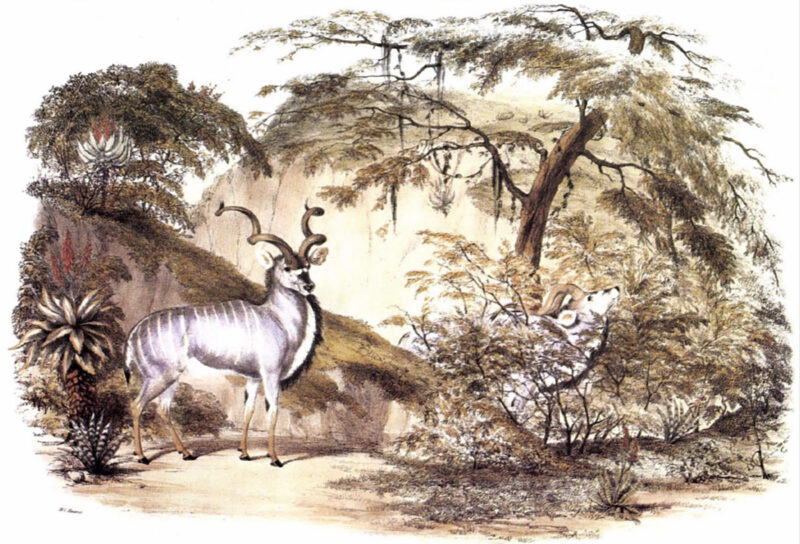

The folio volume that emerged from his “design” excels both in concept and finished creation. Somewhere between 400 and 500 subscribers (authorities differ on the exact number) underwrote the considerable costs of printing the book. Harris painted 31 watercolors especially for Portraits; each image was lithographed from stone in black ink, then colored by hand. The black is uniform on all copies, but the color varies considerably from volume to volume. Similarly, there are several issues of the book and variants of the different issues. Altogether, from 500 to 550 copies were printed.

Perhaps no more than half of the original volumes have survived the combined ravages of time and the pilferings of art collectors. A complete, intact copy of Portraits is worth $12,000 to $20,000, depending on condition, issue, crispness of colors on the plates and other factors.

The lovely color plates include nearly 40 species of big game, ranging from the bulky hippopotamus to the dainty duiker. One of the most interesting plates depicts the quagga, a close relative of the zebra which by the turn of the century had become extinct. Harris writes: “Moving slowly across the profile of the ocean-like horizon, uttering a shrill barking neigh, of which its name forms a correct imitation, long files of Quaggas continually remind the early traveller of a rival caravan on its march. Bands of many hundreds are thus frequently seen during their migration from the dreary and desolate plains of some portion of the interior which has formed their secluded abode, seeking for those more luxuriant pastures, where, during the summer months, various herbs thrust forward their leaves and flowers to form a green carpet….”

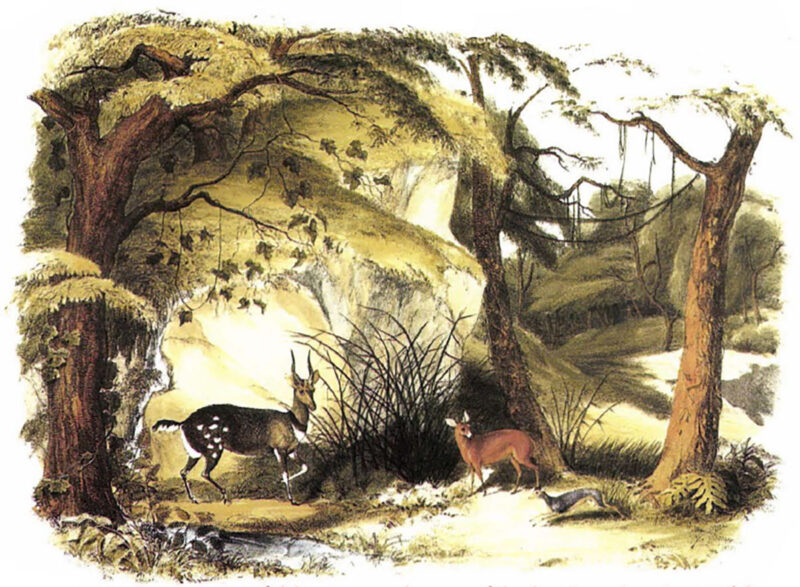

Other illustrations have their own special appeal: A splendid male sable set against a rugged escarpment, a bushbok and grysbok at the edge of a woodland stream, a stately giraffe promenading through a grove of acacias.

Portraits of the Game and Wild Animals of Southern Africa is a work for the ages, but the man who wrought this marvel would live only a few years beyond its appearance in 1840. Harris achieved further fame by heading a mission which established commercial and political relations with the ancient Christian kingdom of Shoa in the mountainous regions of modern Ethiopia. The venture earned him a knighthood and resulted in another book (also prized by collectors), The Highlands of Ethiopia. Harris eventually returned to India where he died on October 9,1848, at age 41. Audubon incidentally, would die less than three years later.

Portraits of the Game and Wild Animals of Southern Africa is a work for the ages, but the man who wrought this marvel would live only a few years beyond its appearance in 1840. Harris achieved further fame by heading a mission which established commercial and political relations with the ancient Christian kingdom of Shoa in the mountainous regions of modern Ethiopia. The venture earned him a knighthood and resulted in another book (also prized by collectors), The Highlands of Ethiopia. Harris eventually returned to India where he died on October 9,1848, at age 41. Audubon incidentally, would die less than three years later.

Harris’ legacies to art and literature will long be cherished. Wild Sports of Southern Africa was the first English language book devoted exclusively to hunting in Africa. That, combined with its enduring readability, earns Wild Sports a prized place on any bookshelf. It is Portraits of the Game and Wild Animals of Southern Africa, however, which must rank as his magnum opus. No other 19th-centurybook can match its size, scope, and elegant illustrations. It joins Audubon’s Birds of America at the pinnacle of great illustrated books on wildlife and the outdoors. As such, it is lasting testament to the man who did for Africa’s big game what Audubon did for America’s birds.

Featuring over 50 illustrations by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure.

Featuring over 50 illustrations by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure.

Over the past three decades Sporting Classics has published more than 100 articles and columns on sport and wildlife conservation in Africa. This anthology, which commemorates the magazine’s 30th anniversary, features the best of those stories. Many talented, dedicated people made this book possible, particularly the authors who eagerly shared their stories. Buy Now