The artistic legacy of Wilhelm Kuhnert, abridged by the first Great War and almost devastated by the second, is known to but a few wildlife art enthusiasts.

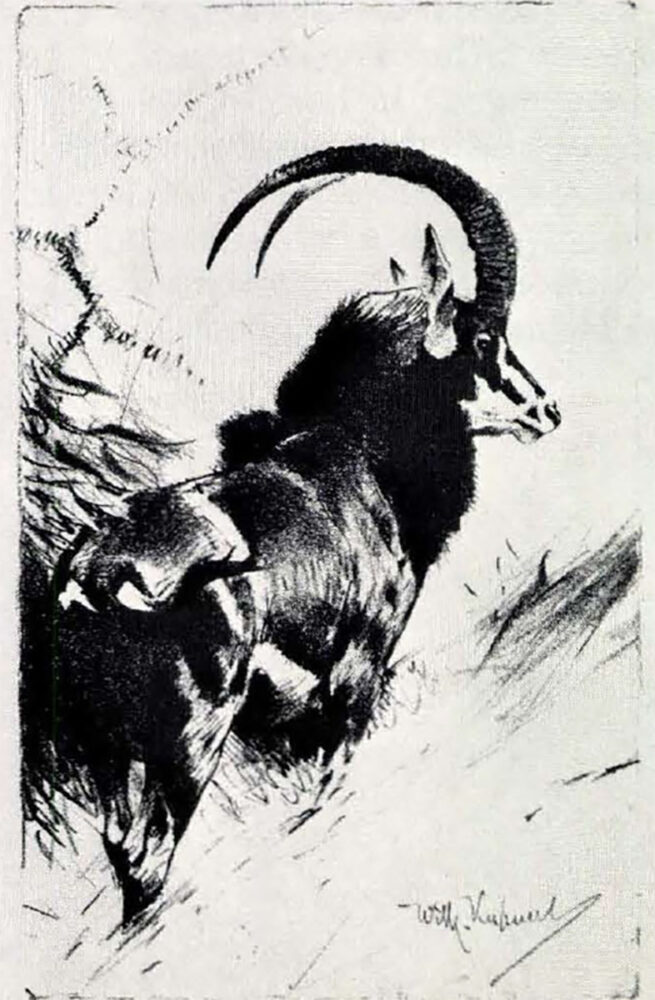

This self-portrait is among 120 etchings reproduced in Kuhnert’s 1925 book, Meine Tiere (My Animals).

On April 30, 1906, Wilhelm Kuhnert and his expedition of 80 porters were encamped along a wide river, less than a day’s march from the East African coast and a steamer that would take him back to Germany. As he sat by the campfire, listening to the familiar sounds of the African night, wrote on the frayed yellowed pages of his diary: “Goodbye my beloved, beautiful land. It is with a sad heart that I leave you. You have offered everything to me and you bowed to me. From day to day, outside influences will change you. It won’t be long and you will be defeated. You can’t resist change; you are much too weak to chase us humans away. Therefore, give what you can and we will gratefully enjoy it while we can.”

Over his lifetime, Wilhelm Kuhnert enjoyed four major expeditions to his beloved Africa, taking its wild game and absorbing its essence and character, but giving back a magnificent chronicle of its land, people and wildlife.

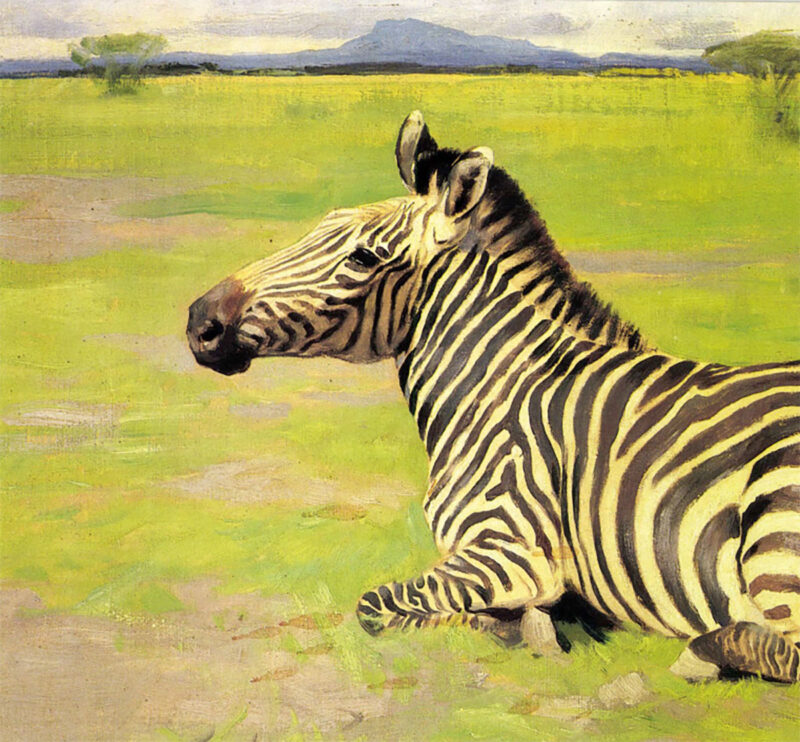

Zebra Resting is among hundreds of Kuhnert animal studies, most done in oil but many in pencil, charcoal, watercolor and gouache. He normally worked on paper when drawing with pencil or charcoal, though

researchers have discovered one pencil sketch on canvas, which he probably planned to paint in his Berlin studio.

The artistic legacy of Kuhnert, abridged by the first Great War and almost devastated by the second, is known to but a few wildlife art enthusiasts. To the rest of the world, his monumental achievements in art and illustration remain unheralded, his personal life virtually unknown.

Wilhelm Kuhnert was born on September 28,1865, in Oppeln, a small city in what is now southern Poland. Even as a child he displayed an amazing talent for drawing and by his early teens, was creating large oil paintings. His father, a government official, recognized Wilhelm’s gift but could not afford to help him further his studies. And so, at 15, the artist left for nearby Cottbus to work as an office apprentice in a machine factory.

Kuhnert continued to draw and paint during his three-year apprenticeship, spending many hours copying the works of the great European masters. One of his earliest paintings depicted the chaplain at the Cottbus church, who along with Kuhnert’s uncle, paid for Wilhelm’s move to Berlin and his tuition at the Royal Academy of the Arts.

Kuhnert continued to draw and paint during his three-year apprenticeship, spending many hours copying the works of the great European masters. One of his earliest paintings depicted the chaplain at the Cottbus church, who along with Kuhnert’s uncle, paid for Wilhelm’s move to Berlin and his tuition at the Royal Academy of the Arts.

At the Academy, another key figure emerged in Paul Meyerheim, who taught a class in drawing and painting animals. Meyerheim helped Kuhnert learn the basics of drawing animals from the inside out — the skeletal structure, lay of the muscles and finally the texture and depth of skin and fur. Kuhnert also studied landscape painting under Ferdinand Bellermann, known for his paintings of the tropics, and before graduating in 1887, became well-versed in a broad range of mediums including oil, pencil, charcoal and chalk.

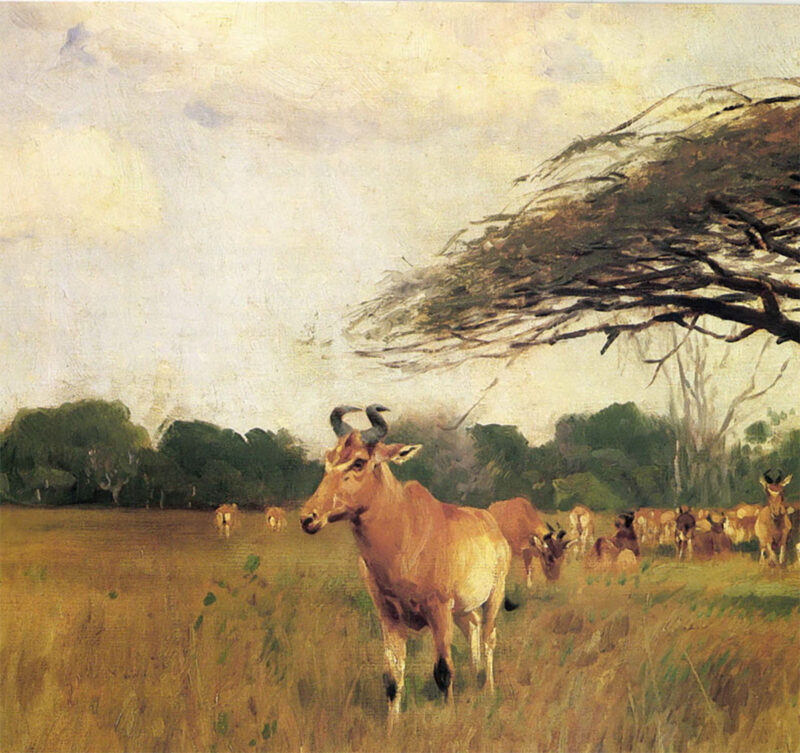

In Lichenstein Antelopes (hartebeest), he enhanced the feeling of depth by placing one antelope in the foreground, then adding several background animals and a large umbrella tree. To heighten distance he lowered the horizon. To achieve a balance between sky, landscape, and animals, he extended the antelope’s head slightly into the horizon.

Prior to Kuhnert’s time, German art had traditionally focused on content rather than on form and painterliness. German artists, dating back to Albrecht Durer (1471-1528), were preoccupied with mythological and philosophical subjects as well as social and historical criticism. By the late 19th century, however, when Germany began to emerge as a leading industrial and military power, the nation of Romantics became a nation of materialists. Before long, German artists were caught up in what one historian described as “a magnificent attempt to affirm reality by and through visual perception.”

Animal painters in 19th century Germany portrayed their subjects realistically, but any attempt to recreate a creature’s habitat was pure fantasy. They simply were not aware of the correct landscape for a painting of lions or elephants, because the only place to study these creatures was at a zoo. Meyerheim encouraged these theatrical backdrops, at one time advising his students: “Do like I do. Place pieces of hard coal on the board, sprinkle sand in between and you have the perfect desert.”

Sable antelope.

Kuhnert, however, would not sway from his determination to paint wild animals in natural surroundings. In the late 1880s, on one of many visits to the Berlin Zoo, he met Hans Meyer, a researcher and part-owner of the Bibliographical Institute at Leipzig. It was a meeting that would shape the young artist’s destiny. Kuhnert revealed his goal of painting wildlife in authentic landscapes. Meyer, who had been to Africa, responded that the perfect place to study and paint nature would be the beautiful Mount Kilimanjaro region in German East Africa.

In 1891 Kuhnert sailed off to Africa, arriving first in Egypt, then traveling to the coast of Tanga (modern Tanzania), where he organized an expedition to Kilimanjaro, Kuhnert remained in Africa for the next 10 months, hunting lions and other big game, while sketching and painting a variety of animals and landscapes.

Cape Buffalo, a magnificent 72 x J08 canvas. The truculent stare of this huge bull reflects Kuhnert’s ability to capture the character of each animal he painted.

During his journey Kuhnert fell in love with what he called “The Promised Land.” In his diary he wrote: “There is something very special to this tropical scenery, something wonderful. It is hard to describe, one has to experience it. I would love to stay here forever.”

The artist returned to Germany in April, 1892, and immediately began converting his field sketches and memories into breathtaking canvases of African wildlife. In 1893 he unveiled his new paintings at the Berliner Art Exhibition and was awarded a Medal of Honor. What Kuhnert had brought back from darkest Africa amazed and enlightened the German public, which had never seen so many strange animals in such exotic surroundings.

Lord of the Jungle, a 14 x 20 oil study

Kuhnert’s renown, and supposedly his income, grew steadily in the years to come, enabling him to travel extensively, first to Switzerland to paint the marvelous Alps, then to the Mediterranean, Netherlands and England. In 1906 he travelled to Ceylon and India, and years later to Sweden and Lithuania where he studied and painted Nordic wildlife, particularly European elk, a close relative of the North American moose. He would return to Africa on three more occasions, once to the Sudan on a hunting expedition with King Frederick of Saxony.

Kuhnert might have spent more time in East Africa were it not for World War I. When fighting broke out in 1914, he not only had to cancel plans for a trip to East Africa, but was forced to remain in Germany over the next five years. In 1916, however, he did travel to Bialowies Forest, the one-time hunting preserve of Czar Nicholas II, which supported a large herd of European bison. Located in western Russia, the region was occupied by German troops.

Whether hunting or painting, Kuhnert would pursue a certain species relentlessly, ignoring all other types of animals for days or even weeks at a time. Only after completing a number of studies or paintings would he switch to other subjects.

Whether hunting or painting, Kuhnert would pursue a certain species relentlessly, ignoring all other types of animals for days or even weeks at a time. Only after completing a number of studies or paintings would he switch to other subjects.

A German writer, after visiting Kuhnert in his Berlin studio, recalled: “He (Kuhnert) described in vivid detail how he approached animals under the greatest difficulties, fighting wind and weather to get close, and how then the artist and hunter become one, when he finally comes almost face to face with the animal, admiring and respecting him, yet fearing for his own life and on the other hand, having to decide the animal’s fate in split seconds. With all his energy and concentration, he tried to capture as much of the shape, look and behavior of the beautiful beast as he possibly could before he finally, saving himself, killed the animal.

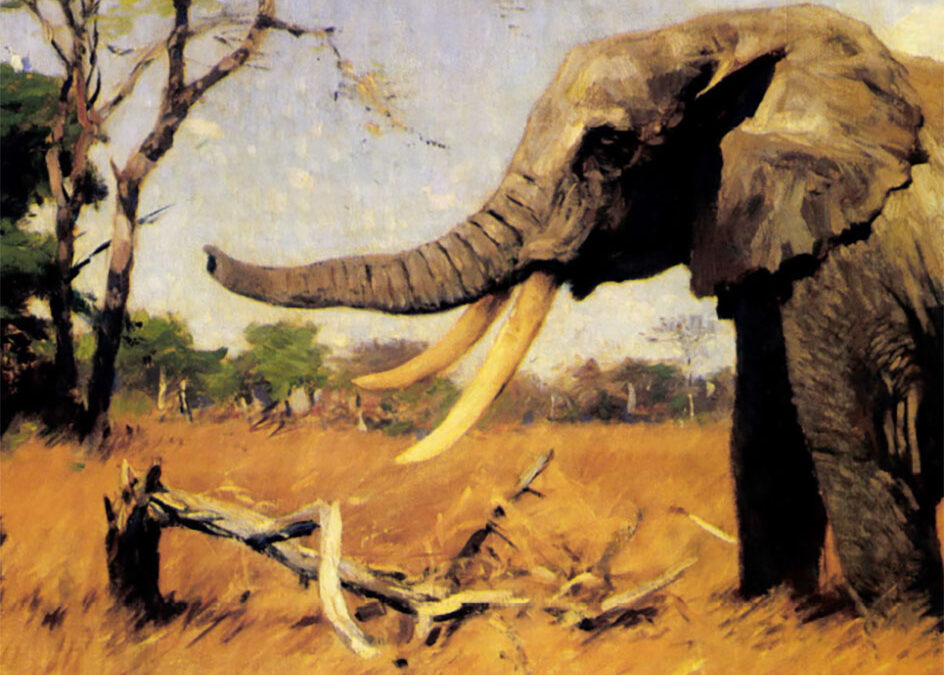

“This artistic yet knightly view of wild animals best characterizes Kuhnert’s personality,” he concluded. In Africa, Kuhnert endured numerous hardships and close encounters, not only with dangerous animals but with African natives. While hunting elephants in an expanse of tall grass, he shot a large bull, stampeding the herd in all directions. In his diary he described the bedlam that followed: “The noise from breaking and cracking trees and branches was deafening and it seemed as if the entire ground was shaking. What an exciting moment, especially when you are not sure if they are coming toward you.”

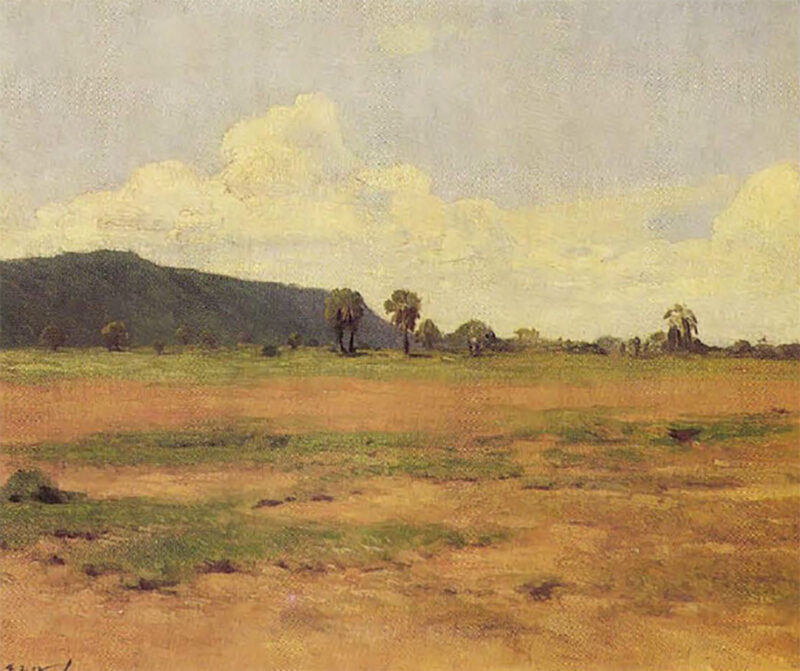

Virtually all of his African landscapes, such as this /6 x 26 oil, eventually reappeared as backdrops for his paintings of wildlife.

Kuhnert usually travelled by oxcart or mule, avoiding existing caravan trails so he would be constantly exposed to unmarred countryside. In areas infested by the tsetse fly, he had to leave his draught animals behind and proceed on foot, often over torturous terrain.

The artist was meticulous in his selection of porters, particularly those who would carry his three double-barrel rifles and his painting supplies. He obviously enjoyed the company of his men and diligently cared for their needs. Shooting enough meat to feed 80 porters appealed to his love for hunting, but hindered his painting and sketching. Quite often he had to abandon the idea of painting a certain animal or landscape so he could put meat on the table. It is interesting to note that on a later expedition to Ceylon, Kuhnert brooded over the ineptitude and belligerent nature of his aides, wishing that he could replace them with African porters whom he believed were harder working and more tractable.

Not all African tribes treated Germans so cordially. On his first safari Kuhnert was confronted by natives who demanded a tribute for crossing their lands, prompting him to write: “The artist’s eye does not know any geographical boundaries.”

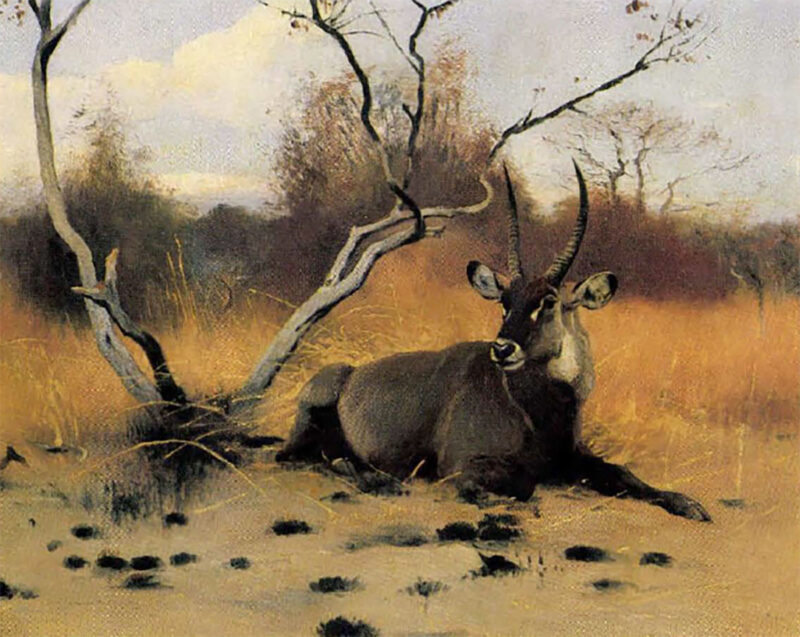

Kuhnert painted oil studies such as Common Waterbuck

(17 x 26)

On his second expedition in 1911, Kuhnert found himself in the middle of the bloody Maji Maji Uprising. During the Uprising, in which some 75,000 natives died, Kuhnert was forced to remain first in Mahenge and later in lringa for many weeks until the rebellion was suppressed.

When he wasn’t dodging fearsome natives, Kuhnert was usually contending with other types of adversity. During the dry season he complained of a blistering African sun that “melted the colors of my palette,” of sudden winds that covered his paintings with black ashes and of tremendous wildfires that swept across the veldt “like waves on the sea.” And when the rains came, Kuhnert wrote of torrential downpours that turned small streams into raging torrents and arid plains into vast marshlands that made travel almost impossible.

Despite the hardships, Kuhnert never lost his passion for hunting and painting big game. He shot dozens of cape buffalo and most likely, all of Africa’s “big five.” His diary jotting from June 29, 1905, reads: “Although I could hear leopards and hyenas through the night, they refused my live goat and my monkey cadaver. They are such good foods for them … I don’t have any better delicacies. I will try somewhere else this evening.”

Lions At Rest (14x 22) oil study.

His artistic preoccupation with lions, elephants, buffalo, giraffe and the like can probably be traced to his strong sense of form and early interest in animal anatomy. He was truly captivated by the grace and beauty of the African lion. Kuhnert eventually painted over 500 canvases of lions, earning the nickname Löwen Kuhnert among his colleagues. He depicted the King of Beasts at rest, at play, stalking its prey and attacking such formidable adversaries as buffalo and giraffe. He was fascinated by their rasping, guttural roars and created dozens of paintings of lions in the act of roaring.

Those who have studied Kuhnert’s works agree that his greatness lies in a rare ability to capture the character unique to each animal. No doubt, his daily contact with wild animals and countless hours of observing them at close range enabled him to recreate their attitudes and expressions, whether it be the kingly glint in a lion’s eyes or the alert, flighty look of a gazelle. Many paintings reflect a hunter’s perspective. In one glorious, eight-foot-long canvas of a bull buffalo, the animal glares at the intruder from blood-red eyes. There is a sinister, malevolent quality to the beast, as if dealing death came as a pleasure.

Most of his drawings are in pencil, though he often switched to pen-and-ink for illustrating books. The sketch of tigers and the African camp scene are among dozens of drawings from Kuhnert’s book, In the Land of My Models.

Kuhnert used pencil for most of his field sketches, but occasionally charcoal or rotel (red chalk). He also completed a number of color studies in watercolors and gouache, and many in oil, although the latter rarely exceeded 20 x 30 inches. But no matter what medium he worked in, he first penciled in the general contours of his subject and prominent features of the landscape.

Manfred Schatz, a popular contemporary German painter, believes that his countryman’s greatest gift was his ability to draw — quickly and with an artistic flair. One early reviewer of a Kuhnert exhibition raved: “Close inspection of his studies, drawings and paintings never reveals an erased pencil line or restored touch of the brush; everything he put down was immediately right.”

Im Lande meiner Madelle (In the Land Of My Models), one of two books that Kuhnert wrote, provides a fascinating look at his diverse hand. The 1918 book, now a valuable collector’s item, contains many pen-and-inks, some with just a few bold, slashing lines to delineate the subject, others more refined with the animal and landscape sharply defined. Scattered throughout the book are pencil drawings, each with rapid, carefree lines that add an air of spontaneity to the scene.

African camp scene.

Between 1914 and 1925, Kuhnert produced 123 etchings in editions from 20 to 100, though most numbered about 60. Almost all of these etchings are reproduced in his second book, Meine Tiere (My Animals), published in 1925.

In 1890 he illustrated Brehm’s Thierleben, which in 1893was reproduced in English by Richard Lydekker as a three-volume set, Wild Life of the World. The comprehensive books contain 72 color plates and over 1,600 engravings, almost all by Kuhnert. His drawings include everything from a sperm whale riding a wave like a giant surfer (obviously he had never observed the animal in the flesh) to diminutive hamsters and mice.

Paging through the books reveals Kuhnert’s extraordinary skill in rendering mammals. His drawings of birds in flight, on the other hand, are often stiff, their bodies distended. His best avian portraits depict tropical species like cockatoos, parrots and birds of paradise which he painted with an impressionist’s palette — bright, almost gaudy colors that dazzle the eye. Interestingly, nowhere in Wild Life of the World is Kuhnert properly credited. The only evidence of his masterful contribution is a tiny signature at the bottom of each illustration.

Kuhnert hunted and painted tigers while on expeditions to Ceylon and India. He imparted the same kingly countenance to his tigers that he did with his lions.

Industrious and regimented, Kuhnert could complete a large oil painting in just four days. A 1981 thesis on his life and work lists 2,659 paintings, most of them depicting wildlife but also numerous landscapes and portraits. He also created a magnificent bronze of a cape buffalo, though only three or four castings were done.

A large body of his paintings was completed after Kuhnert’s last expedition to Africa, when he retreated to his studio to paint dramatic portrayals of African and Asian animals, many on canvases eight feet or longer. Kuhnert had local craftsmen build immaculate frames for many of these paintings. Once a frame was in place, he would make a few last touches to harmonize colors in the painting with those in the frame.

Many Kuhnert paintings were purchased by globe-trotting types or big game hunters, but hundreds found their way into German homes. Sadly, an untold number of his originals were lost during the four-month-long Battle of Berlin and the bombing of other German cities during World War II. Many others were probably carted off by the Russian military.

The German artist created many etchings and paintings of lions attacking their prey; in this case, a big male takes on a mature giraffe, which in real life would probably prove too formidable an adversary

Dieter Grimmig, owner of Galerie G in Heidelberg, the world’s largest seller of Kuhnert paintings and etchings, says, “Kuhnert did so many paintings that nobody really knows how many were lost. I recently saw some old photographs of a Kuhnert exhibition at the Berlin Zoo. I tried to recognize some of the paintings in the pictures but I could only identify two of them. I was astonished because I’ve really seen a lot of his works.”

Today, Galerie G is probably the best place to view across-section of Kuhnert’s art. The gallery has specialized in his work since 1968 and at this writing, has 40 major paintings and over 200 oil studies, etchings, and pencil drawings on display and for sale. A large canvas, incidentally, brings upwards of $70,000, with small studies selling for $3,000-$5,000.

Public exhibitions of his work are more difficult to find. The Rijksmuseum in Enschede, Holland has 20 paintings on display. The Fort Worth Zoo owns 23 oils, all of African wildlife, donated by the F. Kirk Johnson family. Johnson, who hunted with actor Jimmy Stewart, made a number of safaris to Africa and eventually acquired 75 Kuhnert originals. The remainder of his collection is now scattered among Johnson’s heirs. The zoo’s paintings currently occupy a small storage room, although they have been displayed on several occasions. Officials are obviously aware of their priceless collection and hope to construct a special gallery for exhibiting the paintings. However, they have been frustrated in their attempts to finance the construction of a new exhibition hall.

A 15 x 19-inch oil

study of a striped hyena.

Uncovering information about Kuhnert’s personal life can be just as frustrating. Thus far, researchers have found precious little about the artist, save for a few newspaper accounts and six weathered diaries, each comprised of hand-scrawled notes on plain, unnumbered paper. The paucity of information on Kuhnert can also be attributed tohis determination to avoid publicity and fanfare.

Evidently, Kuhnert’s family life suffered from his frequent and long absences. He was married twice and had only one child, a daughter from his first marriage.

During his second African expedition, Kuhnert was thrown from a mule, suffering head wounds and fracturing his left arm. He was taken to a hospital for treatment, though it is not known if he ever completely recovered from his injuries. In 1926, at age 61, he travelled to a health resort in Flims, Switzerland to recuperate “from a previous injury” and apparently to seek relief from asthma, a condition which may have plagued him since childhood. He died on February 11, of tuberculosis, according to one of his three grandchildren, though another believes he was killed in an accident. No one seems to know for sure.

Eighty-one years have passed since Wilhelm Kuhnert expressed his love for Africa’s beauty, his concern for its future. Much of the continent has indeed been defeated, its wildlife and wilderness lost. Thus, we find that Kuhnert’s true legacy is much more than a collection of fine art and captivating illustrations. It is a poignant reminder that we must not only take, but give what we can to safeguard our natural treasures, and not only in Africa, but the world over.

Editor’s Note: The author wishes to thank Gabriele Reddin and Ingeborg Turner for their invaluable assistance in translating various German books and documents. Also, Dieter Grimmig of Galerie G in Heidelberg, West Germany; Russell A. Fink, Russell A. Fink Gallery, Lorton, Virginia; and Fred King, Sportsman ‘s Edge Gallery, New York for their help in tracking down information about the artist. Special thanks to Elvie Turner Jr. and Ken Seleske at the Fort Worth Zoological Park. Except for the tiger painting provided by Mr. Fink, all color reproductions are from the zoo ‘s collection. The Fort Worth Zoo paintings were photographed by Rusty Hill of True Redd Photography, Dallas. This article originally appeared in the 1987 September/October issue of Sporting Classics.

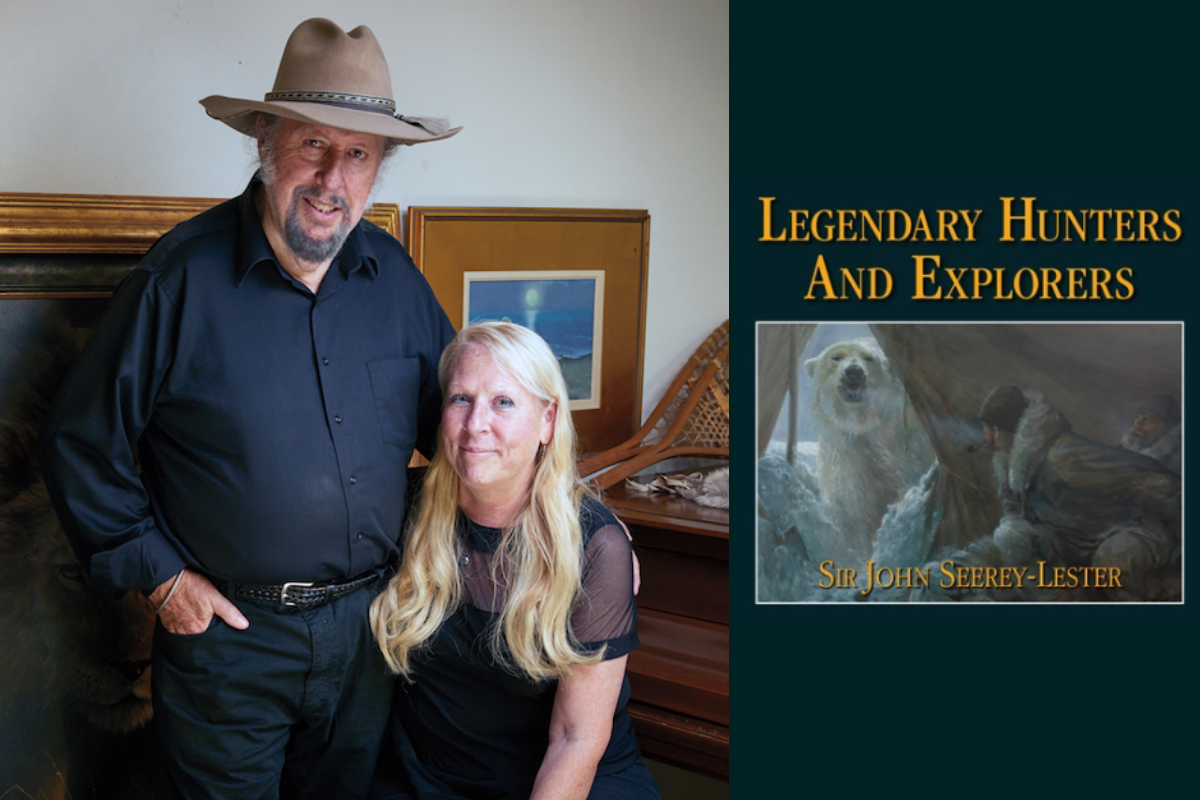

All of the men and women featured on these pages shared an unquenchable thirst for adventure, and a remarkable ability to survive in the face of extreme hardship and dangerous encounters in the wild outdoors. Spanning the years from 1800 to the mid-1900s, the careers of these dedicated hunters and explorers were filled with all sorts of adversity and challenges, which they somehow managed to overcome. Buy Now

All of the men and women featured on these pages shared an unquenchable thirst for adventure, and a remarkable ability to survive in the face of extreme hardship and dangerous encounters in the wild outdoors. Spanning the years from 1800 to the mid-1900s, the careers of these dedicated hunters and explorers were filled with all sorts of adversity and challenges, which they somehow managed to overcome. Buy Now