Turkeys are known for their elusiveness and trickery. Successful turkey hunters must be ever aware, alert…and awake.

I don’t know how many jakes Bob and I passed on during the season, and with a week to go, I didn’t care to waste any time counting. The morning temperatures now were warm, and mosquitoes and blackflies sneaked through mesh facemasks. Since we didn’t catch the dominant gobblers before they found receptive hens, I figured we’d find ’em now. Lots of hens were on the nest, and there were still some corkers that were hot to trot.

Four big birds were roosted behind Leonard’s place. They’d been there for a while, and they spent every night on the sharp hillside. After a few morning wake-up gobbles, they’d drop out of the tree and walk slowly downhill into the field near the river. False Dawn came earlier each day, and on this morning we tucked into the woods under the cover of darkness.

The air was still, and every snapped twig sounded like a blast from a bull horn. I was tired—the bags under my eyes showed it—but I wasn’t giving up. Neither was Bob, and when the sky turned a purple orange, I pulled out my box call and yelped softly.

The gobbles echoed down the valley with such force that they left a wake in the still air. The gobbles came again, again and again, and they came without prompting. I sat back and smiled; these boys were as hot as fish grease, and it was best not to stoke the fire.

At fly-down time they bailed from the tree like 82nd Airborne paratroopers seeing a green light. These birds weren’t shy; in fact, they were downright bold. Early season pleasantries were over, and these gobblers no longer casually dropped into the woods. They didn’t walk shyly down the hill. This squadron was so desperate to get to the field that they flapped their wings on their entire downhill flight. But they abruptly pulled up on the opposite side of the river, where they landed and puffed up in full display.

I sat adjacent to a backwash of swamp filled with skunk cabbage and inhaled that mess for four hours. Those birds were white hot. They’d gobble at a yelp, then double gobble at a purr. But hour after hour all we did was talk. They were hung up good, with come-and-get-it tattooed on their wattles. Around 10 a.m. they got tired of the game and moved on.

I gave a three-toot crow call. A half-hour later Bob showed up.

“Let’s get out of here,” I whispered. “We can follow ’em easily enough, but they ain’t gonna do it today.”

” I saw a mess of jakes at Miller’s Farm,” Bob said. “Let’s fill a tag and come back for these fellas tomorrow. We’re running out of season.”

“My truck’s up the hill, let’s get yours later.”

This is the stuff dreams are made of, but you can’t be caught sleeping when they come around.

By now the sun was up, and it was warm in the woods adjacent to the Millers’ property. The sun was up, the ‘skeeters and blackflies were out, and I set the hen dekes quickly. Bob and I sat close to each other; when the jakes came in, it’d be business as usual. It was like shake-and-bake, which meant I’d harvest one from the left while Bob would take one from the right. All movement was shrouded by the low brush in front of us, and we were comfortable. Who wouldn’t like sitting in piles of larch needles combined with a stack of oak leaves? Heck, it was more comfortable than my mattress.

I gave one soft yelp and sat back to enjoy the day. The sun was bright and the sky was blue, but there seemed to be thunder in the distance. No, it wasn’t that; the rumble came from Bob. Once settled in, Bob conked out. He was copping z’s.

A head popped at the other end of the field. Then another, and another, and another. Man, that was fast, but it wasn’t as quick as the track-star run that dumped half a dozen big jakes ten yards from my feet.

“Bob, you ready?” I whispered. The birds did not mind.

“Bob, wake up. Bob. Bob.” One jake started to mind. He fidgeted a bit and cocked his head back and forth.

“Bob. Bob. Bob??”

One of the bigger jakes on the left took umbrage to my last call. His head went up as straight a setter dog’s perfect tail set. When one bird alarm putted, well, that was that.

“BOOM!!!”

He flopped to the turf in a heap. His wings flapped in the needles and leaves, and I smiled. It was done for today, at least until I saw a shotgun fly through the air.

Thank God for safeties, but then it was followed by a box call, a slate, a pair of binoculars and a pack of diaphragm calls. And there was Bob, flopping around on the ground. His eyes were wide, his face was flushed, and he flapped his arms and legs in the needles and leaves. He looked exactly like my bird, and I did what every good friend would do—I laughed until I cried.

Bob killed a jake a few days later. He tried to make a case that his was a pound bigger than mine, but at that point it didn’t matter. And we never closed the deal on those big toms. Maybe we will this year.

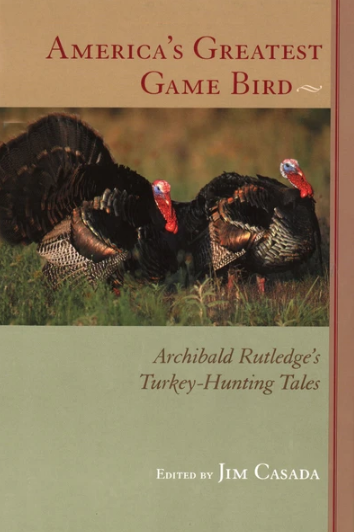

During the first half of the twentieth century, Archibald Rutledge hunted wild turkeys in the woodlands surrounding his ancestral South Carolina plantation. He became wise in the ways of the wary creature and wrote prolifically about the sport.

During the first half of the twentieth century, Archibald Rutledge hunted wild turkeys in the woodlands surrounding his ancestral South Carolina plantation. He became wise in the ways of the wary creature and wrote prolifically about the sport.

In this collection, noted outdoor writer Jim Casada gathers thirty-four of Rutledge’s finest turkey-hunting yarns. Buy Now