“I told him I’d bury him in the meadow and not tell anyone. We shook hands on it, and I can’t go back on my word to him, I just can’t. If I get sent to jail, I’ll go.”

“Ellie, make note of the date, time, people present and that this is an informal hearing with no attorneys present,” Judge Severson said.

“Ellie, make note of the date, time, people present and that this is an informal hearing with no attorneys present,” Judge Severson said.

Ellie scoffed. “I’ve already done that, Charley.”

“Of course you have. Sometimes I wonder why you don’t sit here and I learn to write shorthand,” the judge mused. “And would you refer to me as Your Honor?”

“Charley, let’s get on with it, shall we?” Ellie said, with a look that would melt snow ice. You’re not a Supreme Court Justice, we’re in Sonora, California, and it’s ridiculous to drag young Jake into court after what he’s been through, and you know it.”

“Point taken, Ellie, but it’s my job.” Severson cleared his throat, nodded an scanned the small courtroom. Sheriff Norton, Mr. and Mrs. Bradford and their 17-year-old son Jake sat before him on benches.

“The sheriff invited me to his home last Friday to sample blackberry wine — a fresh batch,” the judge began. “After a few sips, he saw fit to tell me a most peculiar story. He didn’t have to, but Norton felt the need for payback, because for the last 20 years we’ve gone fishing and hunting together. I’ve bested him on weight, size and number and this was his way of saying thank you — letting me share the joy of a few sleepless nights. Sheriff, why don’t you take a few moments and tell us what Jake told you after he got back from his elk-hunting trip.”

“Not much to tell, Charley. Bull Hicks and Jake went elk hunting. Bull died on the trail, and Jake buried him somewhere in the Stanislaus National Forest. Cam back, told his folks, then me and now won’t say where he planted the old fart so we can dig him up and bury him next to his wife in the cemetery. Excuse the language, Ellie.”

“Ellie, make note that Bull is a made-up name we hung on Melvin many years ago,” the judge said, softly.

“That man was as stout as a grizzly bear.”

She scoffed again. “Everybody knows that, Charley.”

The judge nodded and turned to Mrs. Bradford.

“Jake, the State of California passed a law many years ago stating that we can no longer throw a just-died mother-in-law into the rusty bed of a pickup truck, haul her into the wilderness and either throw her off a cliff or roll her down a ravine into a remote canyon, say ‘rest in peace’, and go home and get drunk.

Jake laughed aloud.

The judge did not laugh. He cleared his throat again and spoke.

“The State of California also saw fit to give me a diploma that says I’m a judge. To get that diploma, I laid my hand on a Bible and swore to uphold the laws of the state, and son, I intend to do just that. So you now have an opportunity to tell me why I should not throw your butt in jail or send you to a state or federal penitentiary. Tell me what happened and where you buried Bull Hicks.”

“Where do you want me to start, Your Honor?”

“Well, son, in school I was told to draw a picture on canvas of a nature scene, and was told that my case depended on what I drew, I damn sure would not draw one lone tree, no matter how grand and beautiful it might be, and leave the rest of the canvas blank.

“Then I should start from the beginning.”

“Good choice.” Severson smiled.

“Pop said that when Bull’s hearing went south, and you all had stopped going hunting and fishing with him, he was already wearing store-bought teeth and was as welcome in a deer stand or float boat as a herd of wood ticks with head lice. Bull could hear steam engines and other loud noises up close, but a trout sipping top-water bugs, or a bull elk bugling, were beyond him. So he tended to shout. And when he did, his upper teeth dropped down, the lower ones floated up and out, and it was an unpleasant experience to watch him stuff them back in. But not for me.

“In the nine years since I met and started working for him after school and summers, I learned to love that old man.

“Mom and Pop bought a place three miles down the road from the Hicks when I was eight, and just as we pulled into the yard with the last truckload of belongings, the left rear leaf spring broke. Pop swore, then jacked the buck up, took the spring off and we hiked to the Hicks home. Pop said Melvin Hicks was handy. He was also the best hunter and fisherman in northern California, perhaps the whole state. Pop said he’d forgotten more about the sport than the rest of us could learn in a lifetime.

”We knocked on the door. Ms. Hicks opened it and Pop introduced us. She grabbed my cheeks in her hands, said I was too skinny, marched us into her kitchen, handed Pop a cookie and sent him out to the garage, and then fed me cookies and milk until I thought I’d bust.

”When I got to what she called a garage, I saw a converted barn turned into a wood and machine shop with more tools, machines, smells and stuffed, wild animals than my eyes could take in.

“Mel had sent Pop back home to get the other spring, saying that the steel he’d use to make a new left spring would put the right spring to such shame that it’d break from embarrassment. I just stood in the doorway and stared, and then began to walk around. I wanted to touch, pick up and feel everything, but for some reason I stuck my hands in my pockets instead. I thought Mr. Hicks would want that, me not touching anything.

“When Pop got back, Mel asked me if I’d like to work for him after school and summers with a stipulation that I had to maintain a B+ average. I asked my Dad, and he asked Melvin what I’d be doing. Mel said I’d work with him so he could watch and teach me.

“Over the years, he gave me a Winchester 22 rifle, Remington 20- and 12-gauge shotguns, and a Winchester 30-06 hunting rifle plus two bamboo fly rods and reels, and taught me to hunt, fish, stuff wild animals and work with wood and steel.” Severson nodded. “Ellie, are you still with us, or was he talking too fast?”

“Did you ever see the time when I had to ask someone to slow down, Charley?”

He smiled and said, “Go on, boy.”

“Six months ago, Bull had a heart attack, at least that’s what I thought it was. I got my pickup up to the barn door, and was going to take him to the doc, but he said no. After his wife died two years ago, Bull lost something, slowed down, was quiet … missing her but after that attack he got real slow, tired easily and took to taking afternoon naps. I think he had two more attacks that I know of.

“Six months ago, Bull had a heart attack, at least that’s what I thought it was. I got my pickup up to the barn door, and was going to take him to the doc, but he said no. After his wife died two years ago, Bull lost something, slowed down, was quiet … missing her but after that attack he got real slow, tired easily and took to taking afternoon naps. I think he had two more attacks that I know of.

“Three weeks ago, he asked me to take him elk hunting one more time, and….”

“Where to?” Severson broke in.

“I won’t tell you.”

Ellie laughed. “Good for you, Jake.”

“Ellie, you’ re employment did not come with a lifetime guarantee.”

”Without me, Charley, you’d have trouble opening the door to the courthouse or finding your robe to put on so you’d at least look like a judge.”

“Jake, keep talking,” Severson said, giving her a stern look. Tears rimmed Jakes’ eyes, and he took a long time before speaking. His voice, when it came, was soft and full of hurt. “We got to the trailhead and started out … ““What trailhead?” The judge asked.

“I won’t say. Normally, we reach base camp by nightfall, but Bull was real slow walking, got winded easily and I’d never seen him like that. It hurt to see it. About noon we stopped at the edge of a pretty meadow so he could rest. I took his pack and went to take something out and strap onto my pack, but there was hardly anything in it. No sleeping bag, no food, just a canvas ground cloth, Army issue folding shovel, hand axe, his hat, Bible, a packet of letters tied with a blue ribbon and a picture of his wife.”

“Does the meadow have a name?” Severson asked.

“Yes sir, but I won’t tell you.”

“So far, I can see you in prison stripes, son. Keep talking.”

“Bull was sitting with his back against a fir tree looking off into space. I asked his where his stuff was, and he said …Sit, Jake.'” Bull patted the meadow grass near him. “We’ve got some ground to cover.’

“I sat down.”

“‘Jake, you’re the son I never had. I’m light proud of you, boy. I’ve planned this ever since I had something break inside me six months ago. I’m going to die here, and I want you to bury me in the meadow yonder.’

“There was a lump in my throat when he said those words, and I was scared. I told him I needed to take him back to the truck, but he shook his head.”

“Son, I’m dying, and I won’t be planted in a cemetery. Told Leslie what I was going to do and she agreed. I want to be buried here. This meadow is where I proposed to Leslie 52 years ago after I’d come back from the First World War. It’s a special place, and I want to be out here where the wind blows free, where I can hear the cry of a wolf, feel summer sun and cold winter nights. See shooting stars and watch bear, deer and elk feed on meadow grass and berries. It’s my religion, Jake.’

“’Lord, boy, I got to where I thought like a bull elk or buck deer and came close to thinking like a brook and brown trout.’ He laughed then. ‘You never knew my Pa, but he was my idol — taught me all he knew about the outdoors, how to survive and how to love nature, the good and bad parts — those times when snow blinded us, frost so cold our breath froze on our lips, rain so hard and long we were constantly wet and miserably cold. And there were times when we were lost for a while. And so hungry our bellies ached, times when all we could think about was a drink of water, and a time when we damn near drowned. And then there were those times when everything came together, every sound and smell and sight was so grand and lovely it brought tears to our eyes. Lord, boy, that’s something to remember and cherish. It’s here, son.’

“‘Mel, this isn’t right. I can help you back to the buck. Once we’re home, you’ll change your mind,’ I said.

“‘Son, you’re not listening. I said I planned this. Now, you’re going to have to go back and tell folks what happened. When you do, they’re going to ask where you put me to rest. I’d appreciate it if you’d not tell them. But it’s up to you. I won’t make you promise, because you’ll probably be hauled into Severson’s chambers and threatened.

“‘He’s a good man and one of my best friends, but he takes his high calling a bit too seriously. Sheriff Norton will huff and puff, and threaten to file charges, too. Pay them no mind. But if they do bring charges, I don’t want you to spend a night in jail. You tell them where I’m buried, you hear? And if I’m dug up and dragged to a cemetery and planted there, I’ll somehow haunt their future fishing and hunting trips. And they’ll surely have sleepless nights and bad dreams from guilt.

“‘My God, Boy! Those two men have been my best hunting and fishing buddies for more than 35 years. You can remind them of that.’

“I told him I’d bury him in the meadow and not tell anyone. We shook hands on it, and I can’t go back on my word to him, I just can’t. If I get sent to jail, I’ll go.

“Bull said he wasn’t going any farther, so I set up an early camp. I got firewood and built a pit since he had no sleeping bag, and then I started a fire. It was getting dark by then so I boiled some coffee for us. I poured him a cup and took it to him, but Mel….”

Jake’s voice trembled, tears welled in his eyes and he could not talk for a spell. The words when they came were a mere whisper. “He’d passed away.”

Judge Severson sat for a time staling out the window, his back to the room. A time or two, he’d reach up and rub his eyes with his hands, and without looking at Jake, he spoke softly, his voice cracking. “Son, is he buried deep where wild animals can’t get at him?”

“Yes sir. That night I put his warm coat on him, wrapped him in his and my canvas ground cloths with the Bible, letters and picture of his wife on his chest, his Folded hands over them. I never read the letters, either.”

It took a whole day to dig the grave, about 10 feet deep with a crawl-out slope so I could drag him in and then get out. I carried rocks and placed them over him after putting about four feet of dirt over him. I tried to leave the top smooth — just a bit of dirt piled up so rain would soak the ground and settle the dirt flat again. In time, grass will grow back and no one will notice. No marker was left either.”

Severson wiped his eyes again, his back still turned to the room. Ellie rose and handed him a Kleenex. “Blow your nose, Charley, and then make the only plausible and right decision so these folks can go home. You loved that old man, and you know it.”

“It’s a pretty place with a view of the mountains and timber, open and airy?” Severson asked.

“It’s a pretty place with a view of the mountains and timber, open and airy?” Severson asked.

”Yes sir. I spent three days there after burying him, praying and crying and making sure no animals came. And Your Honor, next fall, I’d like to take you and the sheriff elk hunting. We’ll be hiking through a real pretty meadow on the way to base camp, if you’d like to go.”

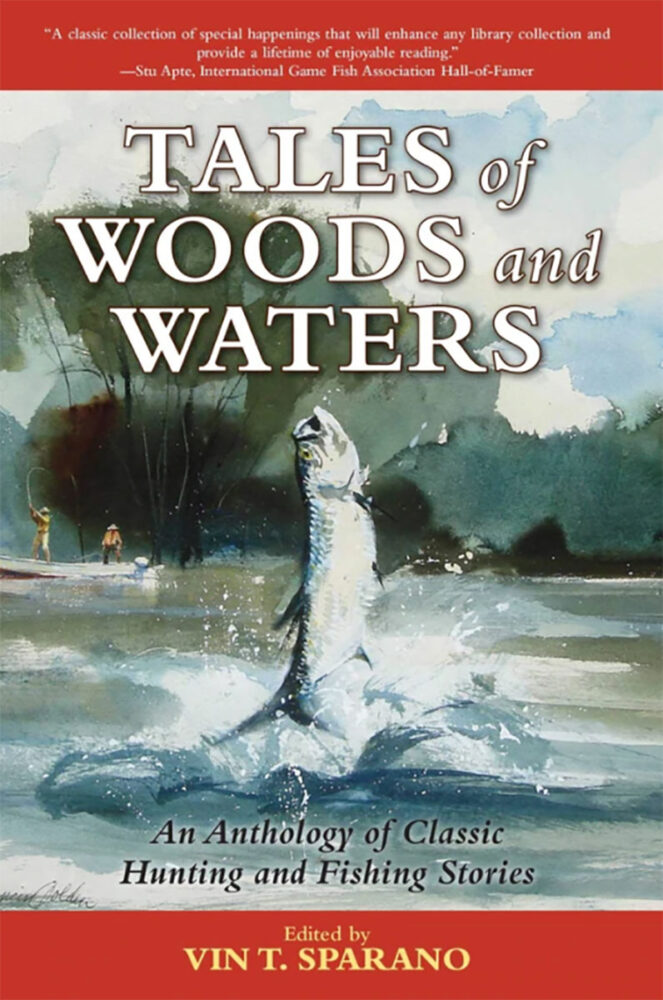

In Tales of Woods and Waters, well-known outdoor editor Vin T. Sparano has collected thirty-seven of the greatest, most enjoyable, and most well-written outdoors stories to have been published. Experience the tension of hunting in the jungles of Tanzania in Jim Carmichael’s “Kill the Leopard,” the joys of your first .22 in Garth Sanders’s “My First Rifle,” the nuances of river fishing in Frank Conaway’s “Big Water, Little Men,” and the enduring challenge of turkey hunting in Charles Elliott’s “The Old Man and the Tom.” Spanning the world and its varied forms of wildlife, these stories demonstrate that no matter where one hunts, shoots, or fishes, the outdoors will always be an important place to form memories that last a lifetime. Buy Now

In Tales of Woods and Waters, well-known outdoor editor Vin T. Sparano has collected thirty-seven of the greatest, most enjoyable, and most well-written outdoors stories to have been published. Experience the tension of hunting in the jungles of Tanzania in Jim Carmichael’s “Kill the Leopard,” the joys of your first .22 in Garth Sanders’s “My First Rifle,” the nuances of river fishing in Frank Conaway’s “Big Water, Little Men,” and the enduring challenge of turkey hunting in Charles Elliott’s “The Old Man and the Tom.” Spanning the world and its varied forms of wildlife, these stories demonstrate that no matter where one hunts, shoots, or fishes, the outdoors will always be an important place to form memories that last a lifetime. Buy Now