We would hunt one last time in the morning, one last time before he went away. I would gift that to myself.

How swiftly and irreversibly, Danny’s season had arrived. From the day almost 10 years before, when first I had invested a portion of my heart in a fledgling youngster who harbored an entreating passion for the outdoors and wild things, I had dreaded it. It happened in a mere turn of the head, it seemed. One year he was a boy of 11 peering down the quaking sights of a 22 at his first squirrel, and when next I looked, he was coming 17 and only a few chapters of geometry from high school graduation. Rapidly, he became more independent, and began to drift from me. Life as we had known it was waning.

Now, with college behind, he was two days and a plane flight from Seattle, where he would begin employment as a forester with a major Northwest timber company. Washington state was a long ways away. Time was close now. Close enough, even, that I might never see him again.

Nevertheless, a boy must become a man, and tomorrow he would leave. There would be the distance of circumstance, and the anguish of increasing absence, and I knew how it would affect me. It would hurt terribly to see him grow away, and take with him days I could never hope to have again.

He could see the gobbler in his mind’s eye, pompous and spread, pirouetting and humming.

Danny had been good for me. He was a sensitive lad, much more so than his father had been. But he had the passion too, and the grit to go with it. And with his had come back some of mine, some of the old zest. We had bought ourselves a couple of bird dog pups, whoa broke ’em and started troubling the local bobwhites again. We got a hound or two and chased the coons out of the roasting ears, punished ourselves in the cold, steely bluster of the Pamlico for redheads, bluebill and cans, and rose up before day in the gladdening of Spring to beat the turkeys off the roost.

Before Danny, I had let myself become old and tired , and might have remained that way. Danny had saved me from myself, at least in the hours we shared. It wasn’t like it was in my day, and could never be again, but it was good. In the boy had burned the man, at least for one last indulgence.

Now he was leaving. But first there was the morrow.

“BOCK!” … “BOCK!” … “Bock!” …”bock!” In the lee of a soft run of entreating yelps, the sharp retort of the gobbler rang through the Springwoods in electrifying, staccato syllables, emanating from the hillside no more than sixty yards to our fore. To the uninitiated, it would have sounded deceptively familiar, like someone pounding a one inch by one inch stake into hardpan with a claw hammer.

Danny whirled to look at me, his face screwed into a question mark.

“Bird!” I confirmed in a whisper.

“Close.”

Hastily, we lowered face nets and jerked on gloves, dropping to the ground by the largest trees available, backs pressed hard against their trunks. Dead still we sat, doing our best to melt into the greening woodscape as the pounding inquest of the aroused bird rose and fell on the neighboring headland, and then gradually faded into the first light of a fresh April morning. Against the acceding silence played the melodious flute and woodwind notes of nearby songbirds, and on the distance floated the raspy bark of a crow. Minutes drained past, laminated in suspense. It was time. Against the prickling uncertainty. Danny plied the age-old invitation.

“Yelp … yelp … yelp … yelp,” ever so softly, in a tender suggestion. The inflection was perfect, the cadence virtual.

Nothing for minutes. Had he quit us? Apprehension hung like a guillotine.

“Gobble-obble-obble!” In a sudden, stabbing proclamation, he hurled his intentions into our face. It stung our tensioned psyches like a backhanded slap.

“Gobble-obble-obble … Gobbleobble-obble.” Somewhere near his original position and moving left across the swell, he periodically beseeched the insolent hen on the adjoining rise to put a move on. He was ready.

“Yelp … yelp … yelp.”

“Gobble-obble-obble.” He was riled, but reluctant. “Gobble-obble-obble.” He continued to pace the hillside, refusing to budge. It wasn’t his place, he argued. Danny waited past the point of politeness, edging him on, making him swelter.

“Gobble-obble-obble.” Still hung up on the hill, he cajoled constantly. I could see him in my mind’s eye, pompous and red, swollen and spread, pirouetting and humming.

An hour into the duel, we were at a stand-off, and progressively his ardor was waning. Time for a trump card. I awaited the next move in a neutral corner, enjoying the drama of the challenge.

“W-h-i-n-e, cluck!, w-h-i-n-e,” Dannypulled the siren’s song from my ancient box call. Nicely done, Danny, I thought proudly. Very nicely done.

“Gobble-obb/e-obb/e. Gobb/e-obbleobble!” It got his goat. “Gobbleobble-obble.” His rejoinder was closer now. Then the woods fell silent again. Minutes trickled by. He was on the way.

Presently, I caught the patriot colors of his snake-like head weaving through the trees, closing. I saw Danny stiffen slightly, and settle into the readied gun on his knees. Forty yards, in and out of a half-strut, then thirty, the bird was drifting slightly left. Danny held his composure, maneuvering his gun over and around an intervening sapling when an obliging tree obscured the movement.

The blast of the shotgun thundered the climax. Danny’s shot took the big gobbler squarely in the head, and a scant two hours into opening morning the dominant tom flopped against the pine needles under the natal rays of the sun, in iridescent bursts of copper, rose, black and green. Simultaneously, Danny was up and running, dodging the sharp shin spurs and grabbing the bird by its feet, lifting it high above the ground. He stood braced against nineteen pounds of pandemonium, the heavy wings buffeting his body and legs in powerful throes, fanning exhilaration into exultation, the stiffened primary feathers reverberating at each beat with the thump of a shaken bedsheet. His face was to the clean, blue sky and there was a jubilant prayer in his eyes.

I was seeing myself again, 60 years ago.

At last, the great wings weakened and fell limp, and Danny, likewise drained from exertion and emotion, laid the turkey gently to earth and collapsed beside it. He was flushed almost as red as the gobbler and his hands still trembled helplessly. I lowered myself against a neighboring sweetgum and we sat reverently, drinking it in.

Danny reached out and smoothed the rich plumage, pensively caressing the glistening green breast feathers with his fingertips.

“Could it have happened more perfectly?” he asked softly.

“Hardly,” I replied.

“I wish I could put him back now.”

“I know.”

Long shafts of saffron filtered through the pale, mint-green leaves of the newly foliated oaks, hanging in shimmering, pollen-impregnated suspension between the pines. Here and there, at their tips, the woodland was splotched with gentle anomalies of sunlight and shadow. Within an adjoining hollow, a wood thrush intermittently anointed the morning with lyrical secrets.

I smiled inwardly. I was at peace. Somewhere along the way, I had done something right.

The morning had been replete. It would be enough. There would be some lonely days in the time remaining, and the festering ache of loss and longing. But it would wear well.

It would be enough.

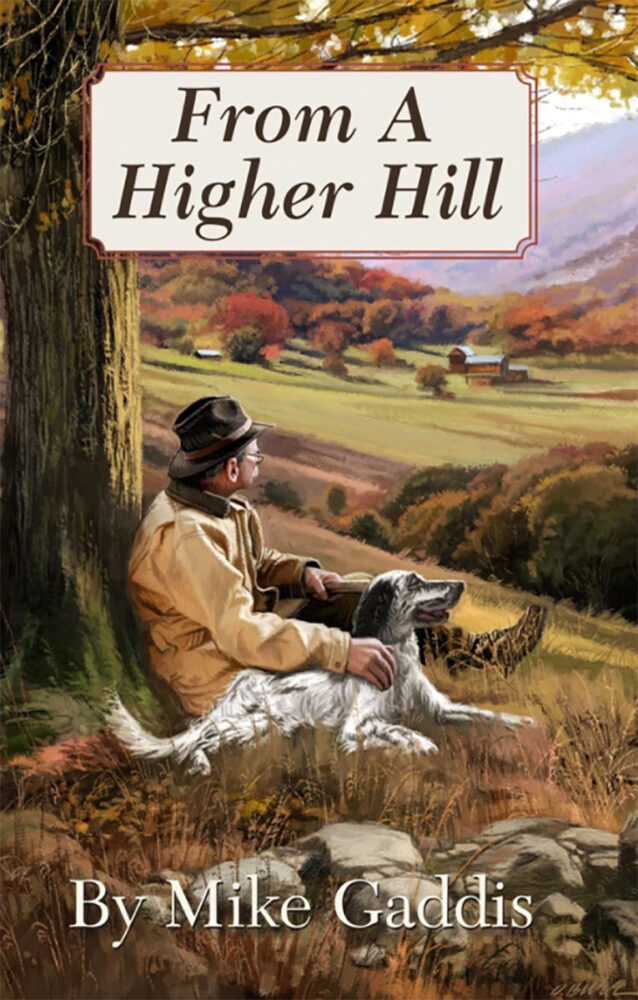

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now