The man who taught me grouse and woodcock lives with his wife in a Vermont hamlet just this side of Canada. He has some gray in his beard these days, but only enough to make him look as wise as his years. He smells like pipe smoke and cherry-wood shavings. He heats his house with cordwood he cuts each summer. He’s whip-skinny and lightning-quick on the banjo strings. His eyes always sparkle when the stove is glowing and there are birds cooling on the woodshed stacks and the talk turns as it does to another belt of the harder stuff.

I’ve tagged along with DB in and out of the seasons for enough years to have grown from boyhood into near middle age, which came on entirely too quickly. Through it all he’s out-walked and out-shot me, and taught me a thing or two about the birds he calls “pa’tridge” and the places where they erupt then disappear — places thick with balsam fir and field edges crowded with young poplars (popple-whips in the language of the Northern Kingdom) where the Holsteins look quizzically at us and scare our dogs to no end. In these places DB has shot at barred apparitions that he lifted from the emerald earth to reveal as ruffed grouse. Were it not for DB, I might still think these wedges of the autumn days were apparitions only, figments of my and my Brittany’s overeager imaginations.

Trouble is, like many of the time-honored teachers, DB is a realist, not a dreamer. On a long-ago day in a long-forgotten covert, DB poked with his Browning a bull of a gray-phase grouse that I’d emptied out on, never ruffling a feather. He stood there with his bird and inquired of my dog why he’d opted not to point that time, and I came over to admire the prize. It was a prize indeed, and I wondered aloud, and not for the first time, whether a guy could get good at shooting grouse without shooting at a lot of birds.

DB pocketed the pat, dug a new shell from his pocket, and evenly answered “No.” He continued, “Not with grouse anyway. And unfortunately, with the numbers what they are in this here Vermont and the pulp cutting all but gone and the posted signs prevailing, you’ll likely never see the number you’ll need to see.”

With that he snapped his gun closed, and we pushed on into the day.

DB embodies what I love and hate of New Englanders, that brash honesty born of hard winters and a spare couple months of high sun. He calls what he sees and he doesn’t make bones about it, and in his way it’s a kindness that drives him.

I likely will never see the 30-flush days in the Northeast Kingdom that he saw in the 1970s, when the hillside farms that had failed a generation before had grown up to alder and aspen and birch. I likely will never see the soaring woodcock numbers that filled his logbooks and dizzied his dogs through the early years until the numbers sufficiently thinned to swear off shooting them. And DB couldn’t help but tell me straight that owing to these things and the trends in land use, I’d likely never get really good, I mean Burt Spiller-good, at shooting grouse. So … No use crying over spilt milk, and there’s still a few birds to look for, and we save money on shells this way, right?

But some part of me, some elementally stubborn part of me, just couldn’t swallow the implication that I’d never see what they saw in the ’70s, when I was still knee-high to a grasshopper. Some part of me wasn’t willing to roll over and grow sentimental of a bygone era that I’d never known and never would. I couldn’t turn my Northeast Kingdom back in time any more than I could return the Vermont landscape to a thing abandoned and taken over by popple-whips and blackberry cane and osiers. Instead, I grew reverent in the love I have for those things and the love I have for men like DB, and I went looking for heydays of my own.

Problem was, try as I might, I just couldn’t find those heydays in Vermont. Maybe they are there still; there are those that say for certain they are, but I wasn’t finding them. Maybe it was just that I was far too set in my ways and too loyal to my aging alder bottoms and apple-tree hedgerows to seek out the young and productive places. But try as I might to have my youth resemble the youth of DB — full of lilting Yankee inflection, Canadian whiskey, and woodsmoke — I couldn’t.

Vermont’s prime had come and gone, and the land I loved nudged me from her nest and compelled me to seek thornier, more overgrown pastures. So, as in all good things that end in hunting or fishing, I headed North and West.

The sweep of upper Wisconsin is like a grouse-and-woodcock hunter’s carnival, with pole-sized aspen that seems to tumble off into Lake Superior, with nary a sign of slowing. I went there on the auspices of circumstance and in the mindset that part of grouse hunting, part of dyed-in-the-wool New England provenance, is knowing that a dearth of birds is part of the beauty.

I went looking for more but expecting less, in a gesture of defeatism that my Calvinist forefathers would appreciate. But the rumors were there, and like any big-eyed bird hunter in the adolescence of his craft, I just had to see what the promises were all about.

Open Shot by Chet Reneson

I drove west under a full-moon sky to a camp on the outskirts of Hayward, Wisconsin, where Mark, a friend of a friend, met me amidst a bevy of Brittanys. He introduced the dogs first, then himself. I arrived late and the morning was soon. My host excused himself to bed after showing me my digs — and the place where the bourbon was kept.

“You’ll like what we’ve got here,” he said. “I can tell.”

How a grouse hunter knows what another grouse hunter will prefer is elemental or perhaps spiritual, but Mark would prove his sentiment correct. I’d been steered his way by like-minded men who, similar to DB, knew that I’d probably never see the best grouse hunting that had ever been. Even among those grizzled elders who’d swear that the good ol’ days could never be topped, there are the precious few who see that the good ol’ days are relative, and when you’re not that ol’ to begin with, your arc of perspective is fairly short. When you aren’t all that ol’ to begin with, sometimes you are still wide open to the fact that what amounts to a pale comparison for your grizzled mentors may be the best you’ve ever seen. I’m quite sure that Mark, trundling off to the bedroom he shared with his Brittanys, had the compassion to understand that. Needless to say, his knowing smile and the brand of bourbon he preferred got me thinking I was in for something great.

Over the ensuing days I walked miles behind Brittanys and saw grouse and woodcock and shot much and hit some, as is the custom with those birds. But the country was so vast, and the birds so regular, and the dogs so good, that the chances of success were proportionally increased. Barred birds got up on the edges of log landings, under blown-down firs, from the gravelly margins, and tamarack edges. They flew as they did back home, but from closer places and with more sympathy for me and my short-barreled 20, and they fell for me as they never had before.

In Wisconsin, I began to feel a fondness for all mankind. On the second day, in a covert we now call The Deuce, I dropped in succession two birds from a group, both mature and both stone dead upon tumbling. To think that I, from my humble origins, could ever have taken a double on grouse made my heart both big and a little magnificent with gratitude, and I felt for a moment as DB Brown must have, when we returned so often to the truck empty handed, save for his stories of better days, and doubles of his own. My history, my stories; I was forging them too, and my heart felt that same thing that his must have a score of years earlier and 1,000 miles east when he had done the same.

Mark and I celebrated in Hayward at lunchtime, with a pint of the local stout and an ice-cream cone to follow. Mark paid. He knew, or seemed to know, that this moment was a defining milestone, a regeneration of a history that I’d feared I’d missed but found instead under circumstances I’d created. He venerated this rite of passage in true Wisconsin style: with ice cream and beer. After a brief recovery period that begged for a snooze, we forged deeper into the October woods.

I returned at length to Vermont with my stories, tail feathers from my birds, and a cocksure spring in my step. In my time away I felt I’d become something I never could have without going and returning, and seeing the bigger piece of popple woods that lingered beyond the Green Mountains. I also found in turning into DB’s yard a newfound commonality borne of experience. I’d meet my mentor, my friend, on level ground, explain to him how I now understood the time that he spoke of, the time when the woods filled to overflowing. The wayward son of sorts, but one returning home having forged a history of his own, by his own hand, and his own well-hurled pellets — albeit not in our revered Vermont coverts — but nonetheless in the grouse woods, in a land familiar in composition and structure. I was so eager — and so proud.

DB’s wife Ann was in the garage when I pulled up and loosed my dogs for a hello. She was putting the snow tires on the car, and she straightened and stretched and smiled to see me, and as always she petted the dogs. Certainly, she could sense that I had news.

After the pleasantries, I asked the whereabouts of DB.

“Oh, you missed him,” said Ann with an innocent smile. “He headed out of here three weeks ago on a road trip west. Hunting grouse with a couple of buddies. He’d been planning it for a year or more; surprised he didn’t tell you. Said there weren’t enough birds left around here. Seems he won’t be home for another week or so, but apparently they’re making quite a dent out there. He’ll be glad to hear you stopped by.”

Subscribe to Sporting Classics today for more great stories, or pick up a copy of the current issue on newsstands now!

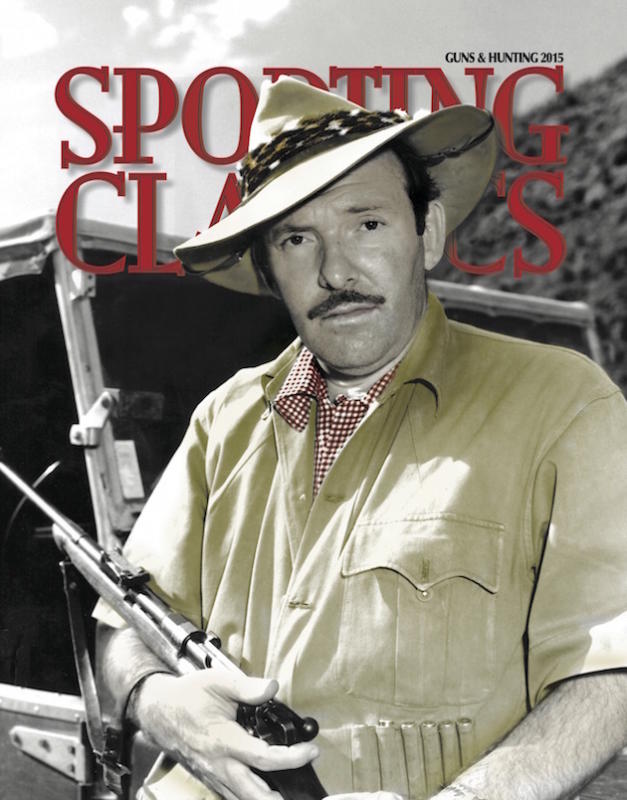

Cover Image: October Ruffs by Eldridge Hardie