My life outdoors began as an escape, a way to get away from people, yet now I’m involved in the outdoors because of people — the people I’ve met there.

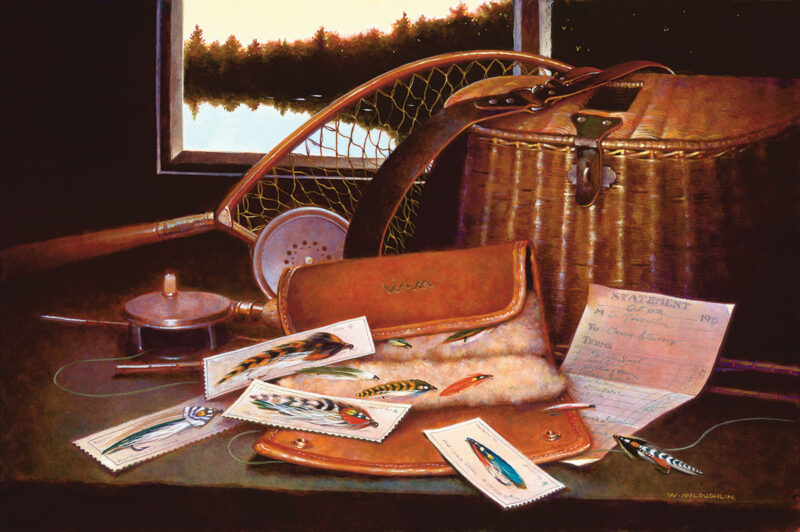

Magic in the Mail from Maine presents some of Carrie Stevens’ famous patterns along with fly-fishing gear from the 7930s.

Over the years, the most common question I’ve been asked about my painting is “How did your art evolve into such extremes, very serious on the one hand, and so eccentrically humorous on the other?”

The question has puzzled me because I’ve regarded painting as a conversation between the artist and the viewer and not all conversations are serious, are they? Perhaps my work simply reflects a life of rich extremes and ironies — or not enough therapy . . ..

I was born in Wales April of 1944, just in time for the divorce. I may have been a factor. Mum and I moved back to London, packed into a small house on the edge of Hampstead Heath with her volatile mother, sister and two older brothers. There we remained, fighting for the next seven years like stoats in a breadbox, until Mum hissed a Celtic goodbye from the rail of the Mauritania, “Bugger all of you!” We were sailing for a new beginning in the States, so once England slipped beneath the horizon, Mum’s contact with “family” was over for good.

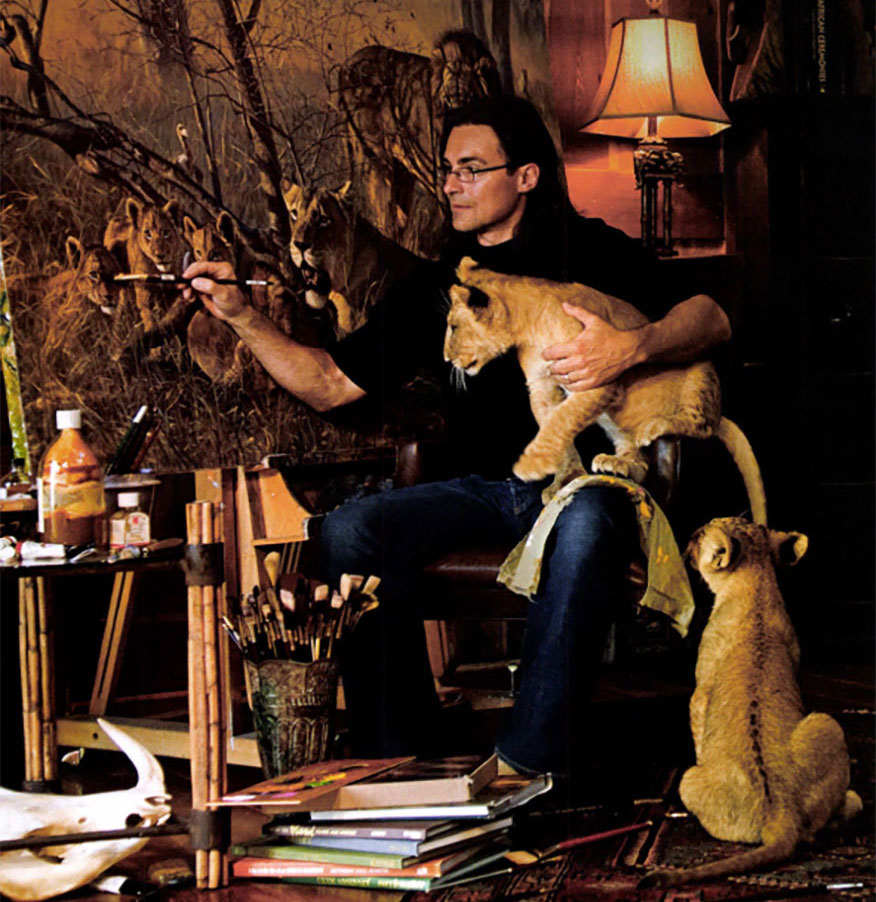

The Visitor

Credit for my earliest yearnings for the outdoors belongs to the two Americans who entered my life that year. One was my brand new stepfather, a sadistic Navy drunk who lived long enough to break my mother’s spirit and whose tyrannical rages made the nearby Florida swamp immediately more appealing than our house. The other was Mark Twain, whose vivid descriptions of boys drifting downriver on a raft fueled a dream of liberation. Someday it would be Tom, Huck and me . . ..

In the meantime, my Little Lord Fauntleroy accent posed a wee problem for the feral urchins populating our Florida neighborhood. “Ya’ll shore spake funnee!” soon devolved into regular pummelings, which only subsided when they discovered I had both a knack and a willingness to catch snakes — particularly water moccasins. (It was a skill I began honing after learning that even garter snakes terrified my stepfather, who furiously minced them with a hoe.) Unfortunately, the yardstick-flailing nuns of parochial school were also inflicting additional speech therapy. In two years my accent was gone and my desire to escape into the wilds had become an obsession.

Viewing homework as clear evidence that teachers had failed to do their job while they had me trapped in a classroom, I found much more time available for the woods and swamps if I simply didn’t do it. Instead, I took the logical expedient of using my watercolor skills to alter my invariably poor report cards. Dismal D- became a happy B+ in seconds, and a revised C- showed my promise as C+. Cards were signed, my creative modifications removed with a drop of water and a tissue, and the cards returned to the teacher. Everyone was happy . . . particularly me.

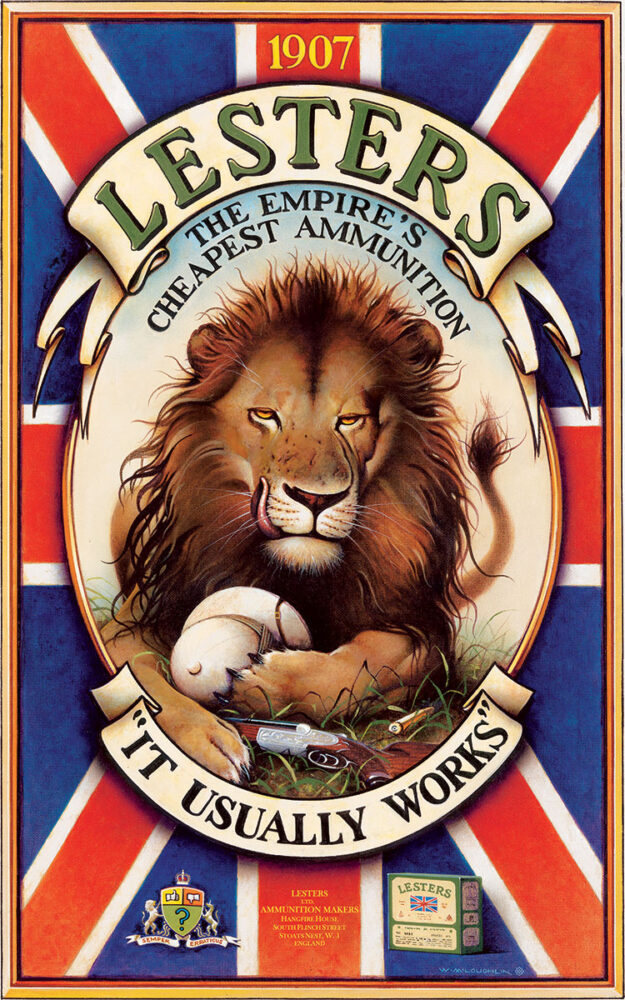

Lesters Ammunition, Lion is a nod to the author’s British heritage and Africa’s storied hunting tradition.

I’d been amusing myself drawing and painting since age five, but over the next few years the possibilities of art became more apparent. I used artwork to impress various grade school vixens, buy off bullies and subversively entertain the other noble intellectuals flanking me in the back row. When I wasn’t roaming the woods or swamps, I was painting pictures of the creatures living there. I was getting away to safety both physically and creatively. Most importantly, I was having fun! The only adults allowed in my world were Roy, Gene, the Lone Ranger and Ramar of the Jungle. Of course, I’d make an exception for my “real” father when he came for me.

A further inducement to develop my artistic skills occurred when the financial floodgates opened and I received hefty commissions to immortalize in oils the countless cats, dogs and rodents owned by devoted art patrons of the neighborhood. Alas, however, the lucre was poorly invested and soon lost in a vast assortment of plastic models and custom car magazines. (Little has changed in that regard, except it is now splurged on firearms and fly rods.)

After “failing to work to his potential” in 11 different schools scattered about the country courtesy of Navy moves, I was released from the dreary bonds of high school and enrolled in the most highly esteemed institution available for those possessing exceptional artistic ability and a desperate need to get the hell away: the United States Marine Corps! It was my Olive Drab Period.

While the Corps “fine arts program” was limited to painting the rocks outlining paths in the barracks area, their outdoors curriculum on the Pendleton campus was exceptional and included hiking, backpacking, running, camping, various survival schools and even a marksmanship program! The fun diminished in ’65, however, when my Excite-O-Meter was finally pegged in a mined LZ South of DaNang.

MCLoughlin painted The Catamount shortly after encountering this angry cougar in his den.

Following my matriculation from the Corps, I entered college, married and soon landed my first assignment that combined my need to be creative with my need to be in the outdoors. My wife, Jackie, and I were commissioned to backpack throughout the South Pacific photographing native life from Hawaii to New Guinea for an anthropology book. After the seven-month expedition, we found employment in New Zealand’s publishing and advertising industries, taking forays afield for trout fishing and hunting the delicious toheroa (a bivalve molluse).

Shortly after our return to the States, with no experience whatsoever, I submitted an illustrated humor article to Playboy Magazine. Co-authored with my friend, Scot Morris, it was a cheery Darwinesque tour of the whimsical animals mutated by World War XI. When the article won Playboy’s Best Satire of 1973, my totally unplanned career as a humorist was launched! One month I was a lowly surfer, the next month I was read by seven million people. What do you think about that, Dad?

Almost immediately, National Lampoon sent PJ O’Rourke to our home in San Diego with an offer of work, subject of course, to a satisfactory (free) cultural tour of Tijuana in my VW. Then Esquire called, National Geographic, Ford and Texaco. A couple of years later, Johnny Carson laughingly showed my “aged” portrait of him on the “Tonight Show.” When he retired years later looking exactly as I’d painted him, I had the last chuckle.

The phone kept ringing. Ad agencies hired me, not for humor, but for conceptual paintings. The subjects ranged from wildlife to celebrity portraits, from high-tech equipment to clipper ships. Commercial clients including the City of Chicago, Adidas or CNN were exciting and gave the added benefit of taking the pressure off my own painting. I could paint what I wanted absent any need to repeat what was selling like some artsy-craftsy Xerox machine. Today, I still paint in those same three categories — personal, commercial and humorous — thoroughly enjoying the challenges of each.

The artist enjoys inventing fanciful

products he believes sportsmen would love to own, like a

special tonic for gun-shy dogs.

Over the years Jackie and I embarked on numerous wilderness trips lasting weeks at a time. Dropped off by floatplane, it was just the two of us, plus our food, gear and a canoe. I had at last made the great escape. I was with someone I loved in faraway places where I fit in — Labrador, British Columbia, the Northwest Territories. Through my paintings, I tried to describe the mood of what I felt out there and its spiritual aspect. I didn’t care about showing every hair on a deer or bobcat, a parlor trick for me that was much more about endurance than art. I worked to capture a sense of intimacy, something dream-like, both eternal and fleeting, whether quiet or dramatic. That was what I saw and loved in the painted efforts of my heroes Dali, Hopper and above all, Vermeer. They used their imaginations, not just their hands.

Through the people and events experienced on hunting and fishing trips, I also saw the ironic, the comic and the tragic, eventually using them as subjects for 20 years of contributions to Sports Afield, Field & Stream and other outdoor magazines. The more I entered the wilderness, the more it fueled my creativity until both art and adventure were my sanctuary.

Perhaps it sounds selfish, but the truth is that I’ve always created the paintings and humor articles for myself. I needed to see them, to relive the experience and to be entertained. Once that was achieved, I just hoped like hell someone else enjoyed them enough to want them. So far, I’ve been lucky.

Hertari! The Movie Poster is a customizable print that pays homage to women hunters and their safaris.

Throughout the process, I’ve been blessed to spend time with legendary outdoors writers, gunsmiths, guides, knife-makers, big game hunters and master fishermen. They are my people! To paraphrase one of my clients at a recent Safari Club convention, “I come here year after year because these are the only people I can really talk to!” It’s a sentiment that also reflects the reason why my commercial work is now devoted exclusively to clients in the sporting industry. After a lifetime immersed in the outdoors and studying its history and using the gear, it’s exciting and interesting to create ad campaigns, product designs and illustrations for clients such as Jarrett Rifles, Cabela’s and Knives of Alaska.

My life outdoors began as an escape, a way to get away from people, yet now I’m involved in the outdoors because of people — the people I’ve met there. While that is indeed ironic, a far greater irony occurred when I finally met my real father. As a boy, I had expected him to come at any moment. Now, I was middle-aged and he was an old man. It had taken all the courage I could muster, but only a half-dozen international calls to find him. Until then, I’d never seen him, not even a photograph. I’d never received a single card or letter yet, suddenly, there I was standing outside my father’s house in Wales, just a few miles from where I was born.

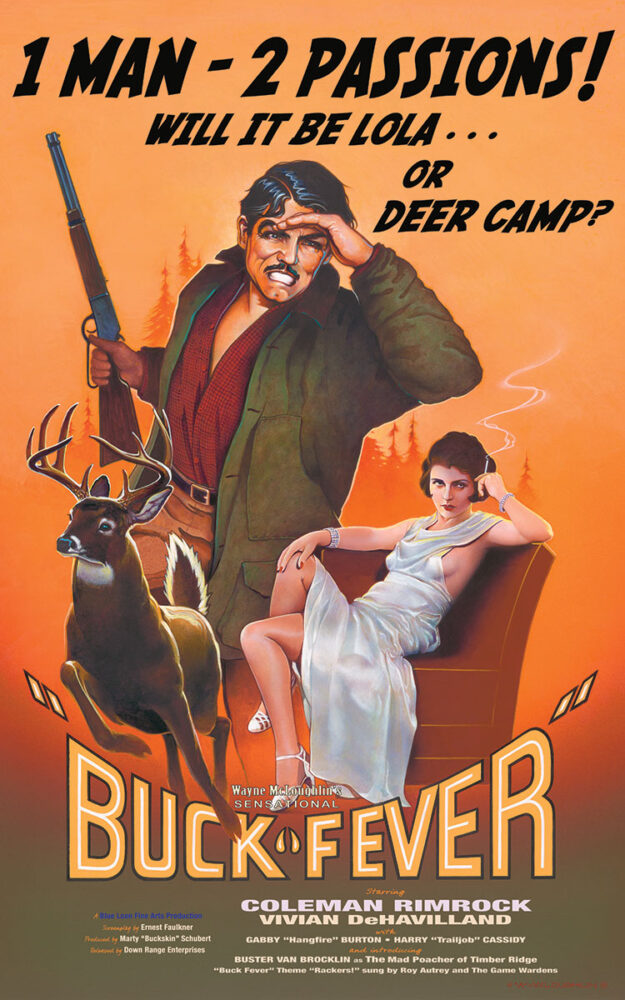

In his print Buck Fever! The Movie Poster, MCLoughlin conveys the perennial dilemma of every male hunter. We all know how this movie ends.

Jackie and I were met at the door and introduced to his second wife, Alice, and his stepson, Colin, a man just nine days younger than me. We were ushered into the living room where, to my astonishment, I saw the mantelpiece and every available shelf crowded with countless fishing awards and trophies. The walls were a jumble of my father’s watercolors and photographs of my father and his stepson holding up gorgeous trout they had taken on the streams of Wales, Scotland and England. Centered amongst them, in an apparent place of honor, a fading color photo captured their beaming pride as they held up a handsome brace of salmon. The inscription read, “Ireland, 1965,” the year I was wounded. An understudy had replaced me!

Our meeting went well enough, but further communications were sporadic at best until his passing ten years later. I realized that I had searched for my father; he had not searched for me. Simply too much water had passed under the bridge and it was water we had never fished together.

I’ve long known that the outdoors is my true home, but during that journey of discovery, I learned a most valuable lesson. A map and compass, waterproof matches and a knife may be very useful, Pal, but whether in life or in the wilderness, when things get serious, by far the most important survival tool one can possess is a damn good sense of humor.

Finishing the final book in the iconic Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers is the epitome of Sir John Seerey-Lester’s spirit. Filled with over 120 paintings and 45 descriptive chapters, the new 200-page book relives the compelling stories of 25 acclaimed hunters and explorers.

Finishing the final book in the iconic Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers is the epitome of Sir John Seerey-Lester’s spirit. Filled with over 120 paintings and 45 descriptive chapters, the new 200-page book relives the compelling stories of 25 acclaimed hunters and explorers.

Amid his fight against cancer, Sir John Seerey-Lester was working tirelessly on his final book of the Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers, when he passed away in May of 2020. He is survived by his wife and fellow artist, Suzie Seerey-Lester, who carries his torch with vigor and pride. Buy Now