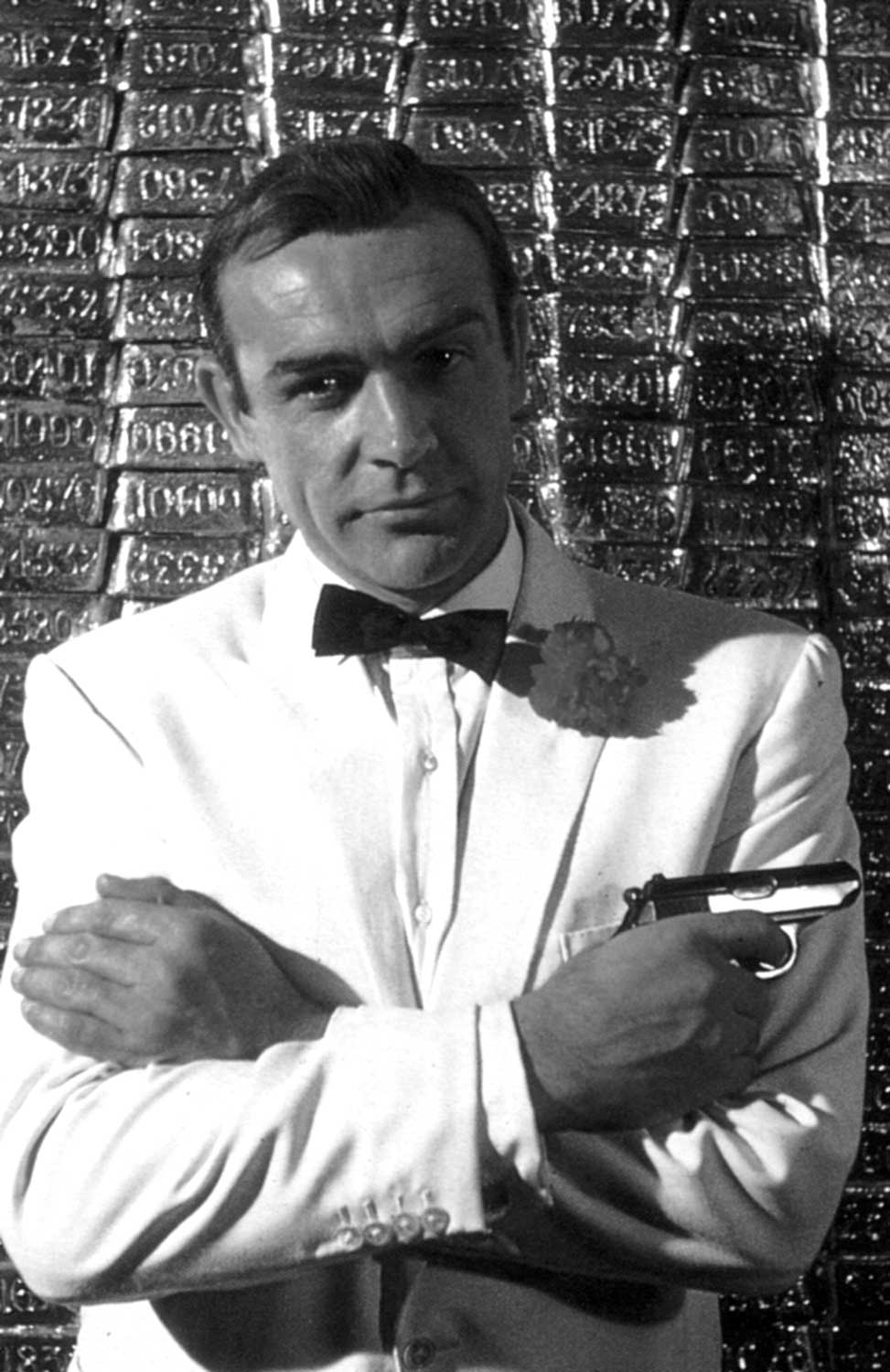

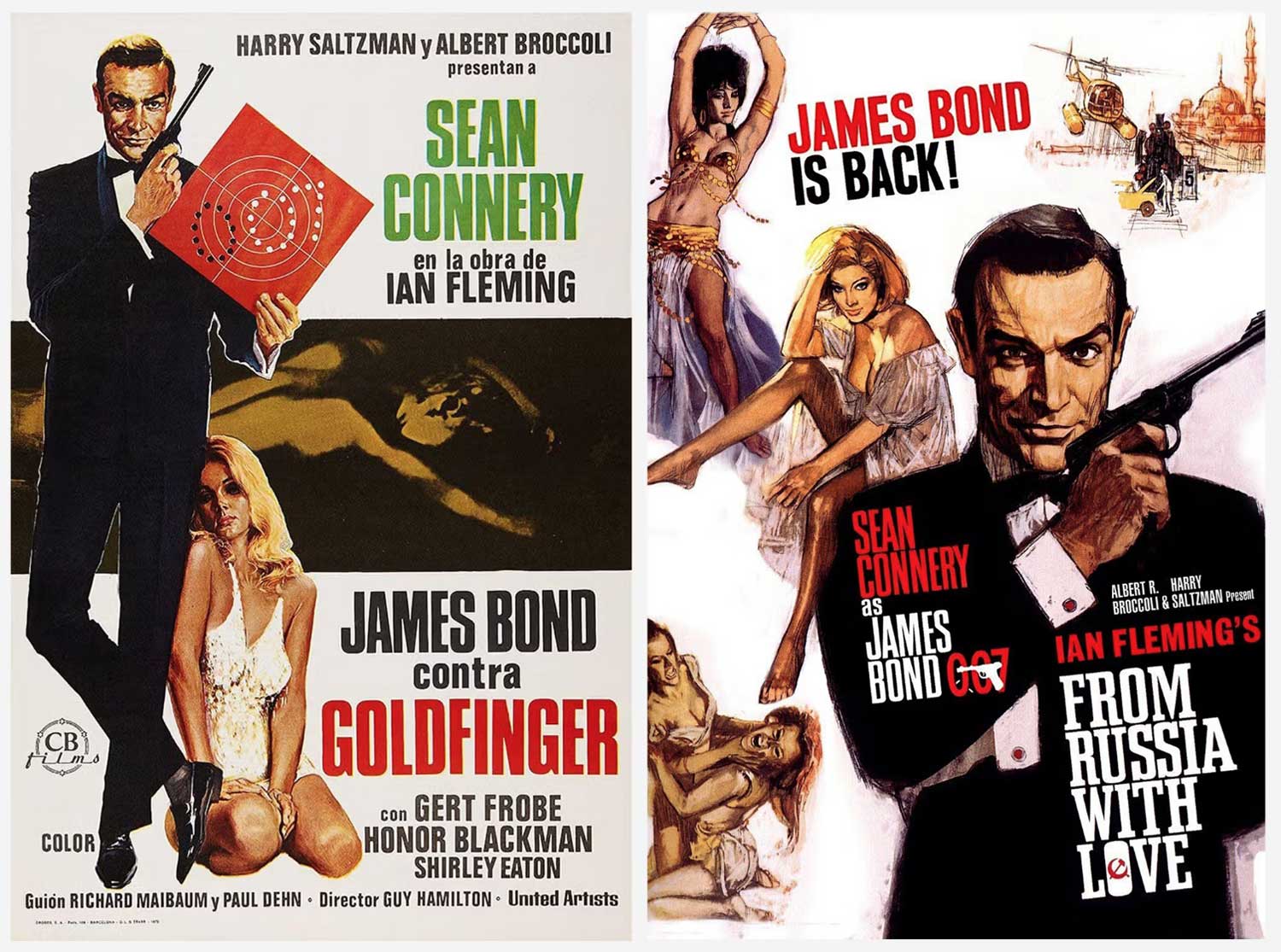

My name is Bond, James Bond.” In the annals of the spy thriller genre, no other secret agent has achieved the iconic status of Ian Fleming’s 007. An agent with lethal skills and a license to kill, Bond, as his millions of fans know, is a dashing and debonair figure, a man with refined tastes – right down to the preparation of his martinis and his choice of personal sidearm.

A precision-engineered and utterly reliable pistol that features elegant, flowing lines, the Walther has “Bond” written all over it. Understated in a gentleman’s way, but deadly in the right hands, the PPK was just the right fit for the world’s most dashing spy. And, to top it off, its slim design allowed his bespoke suits to drape perfectly, without a hint of a bulge.

By the time Sean Connery teamed up with a Walther in the first Bond film, Dr. No, produced in 1962, the PPK was already a pistol of notable acclaim. Like a gold Dunhill lighter, a Rolex Oyster Perpetual or a Mont Blanc pen, the Walther PP and PPK are among the relatively few products that reached the rarefied stratum of the true classic, the ne plus ultra of its type.

Walther’s history, however, hardly follows the script of the typical corporate success story. Instead, it is a tale that has as many twists and turns as a Bond thriller, with chapters that include two world wars, two dictatorial regimes and several world economic crises. For the company, it was nip and tuck more than a few times, but through it all the Walther family seemed to understand that if there is a will, there is a way.

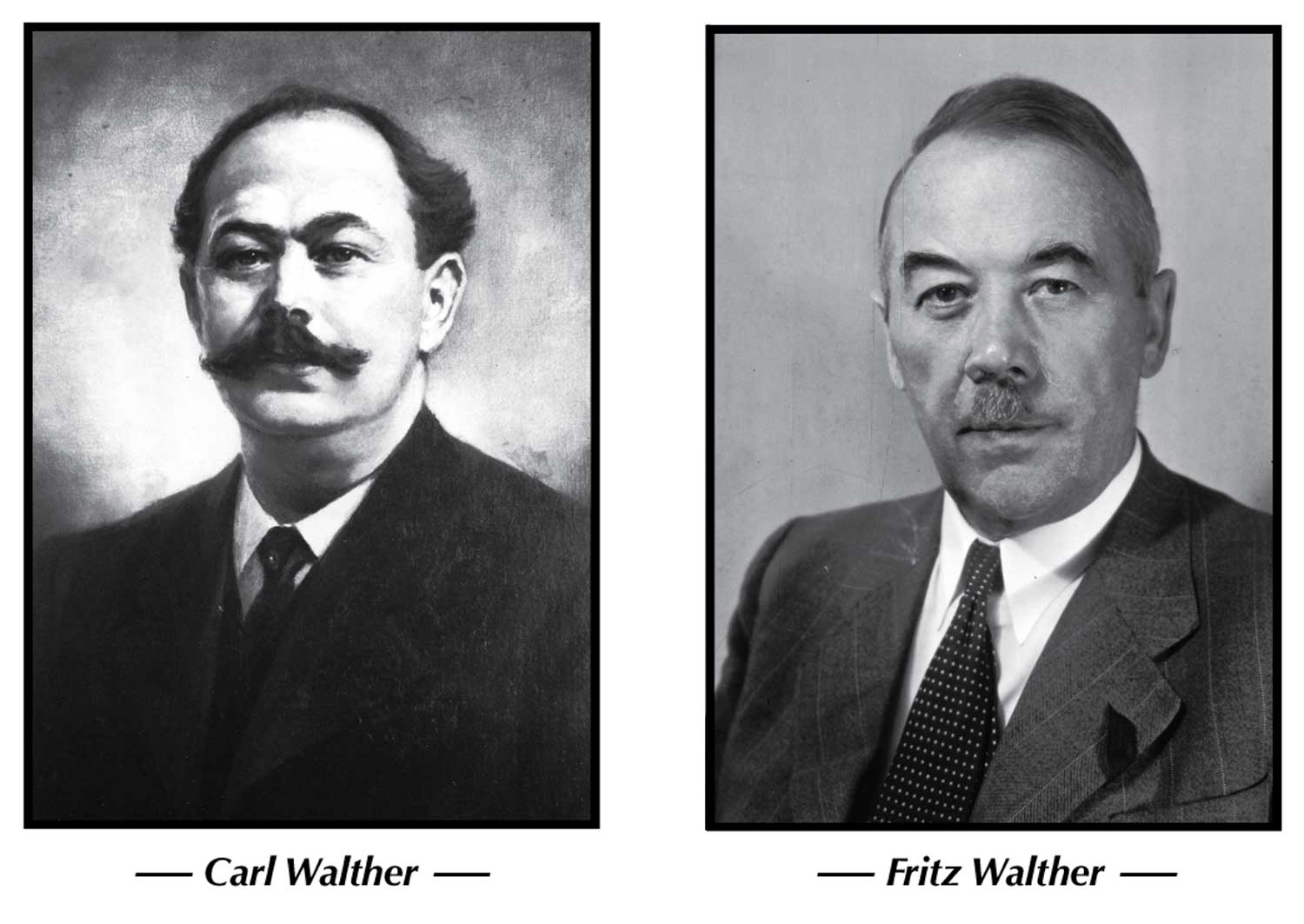

After more than a decade apprenticing in the rifle-making trade, 28-year-old Carl Walther struck out on his own in 1886 and opened a small workshop in his hometown of Zella St. Blasii, a hamlet in an area of Germany (Thuringia) long known for its firearms manufacturing. Responding to the growth in target-shooting participation in Germany, Walther’s first products were Schuetzen rifles, the classic offhand target rifle of that era.

As his business grew, Carl Walther invested in a three-story addition to his original workshop in 1903, and his sons, as they came of age, began their apprenticeships as rifle-makers in the family business. While broadening his manufacturing experience in Berlin, Carl Walther’s oldest son, Fritz, noted that self-loading pistols were quickly gaining favor over traditional revolvers, especially compact models that were convenient to carry for personal protection, a growing need in that era. He was able to convince his father to invest in the development and production of such a pocket pistol, a shift that would ultimately define the course of the company.

While early production of the first Walther pistol began in 1908, the company received its patent for a “blow-back weapon with a fixed barrel” in 1911. The Walther Model 1 was a compact pistol chambered in .25 ACP (6.35mm Browning) that perfectly fit the bill as an easily concealed and lightweight handgun. Only a few years later Walther expanded its product line with its first larger handgun, the Model 4 chambered in .32ACP (7.65 Browning).

On June 28, 1912, Austria’s designated heir to the throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated in Sarajevo – an event that dragged the European continent into World War I. The founder of the company, Carl Walther, died in 1915, leaving management of the business in this turbulent time to 25-year-old Fritz Walther who ably took charge and would, in fact, continue to lead the company for most of the next half-century.

Walther expanded its factory to accommodate a wide range of war-time demands yet continued to produce its line of pistols and even upgraded and improved its standard models. The Treaty of Versailles in June 1919 ended World War I but also marked the beginning of a period in Germany that was characterized not only by great political and social upheaval, but also economic hardship fueled by hyper inflation. For example, postage for a standard letter soared to two million marks.

Potential sales of pistols at this time were limited at best, and Fritz Walther understood the company needed to diversify its product line to survive. Capitalizing on the factory’s precision engineering capabilities, Walther turned to manufacturing adding machines, creating a new division of the company that would be profitable for years to come. It was the first time that Fritz Walther needed to have a trick up his sleeve to keep his family’s company afloat in a perilous time. It would not be the last.

While many German firearms makers went bankrupt in the post World War I era, Walther remained financially stable and continued to develop new models. In 1920 the company introduced its Model 8 – the precursor in many respects to its famed PP (Polizeipistole) series. In this time frame, Fritz Walther also designed an autoloading shotgun as well as a line of marine flare guns and starter pistols.

Walther introduced the PPK (Polizeipistole Kurz) in 1931, two years after the PP hit the market.

Even in this difficult era Walther understood that creating new and innovative products would give his company an edge over the competition. In the mid-1920s his design of a new pistol with a double-action trigger also featured a safety and decocking lever for the hammer, and by the end of the decade set the stage for the company’s signature handgun, the Walther PP and its compact brother the PPK, both originally chambered in .32ACP (7.65 Browning).

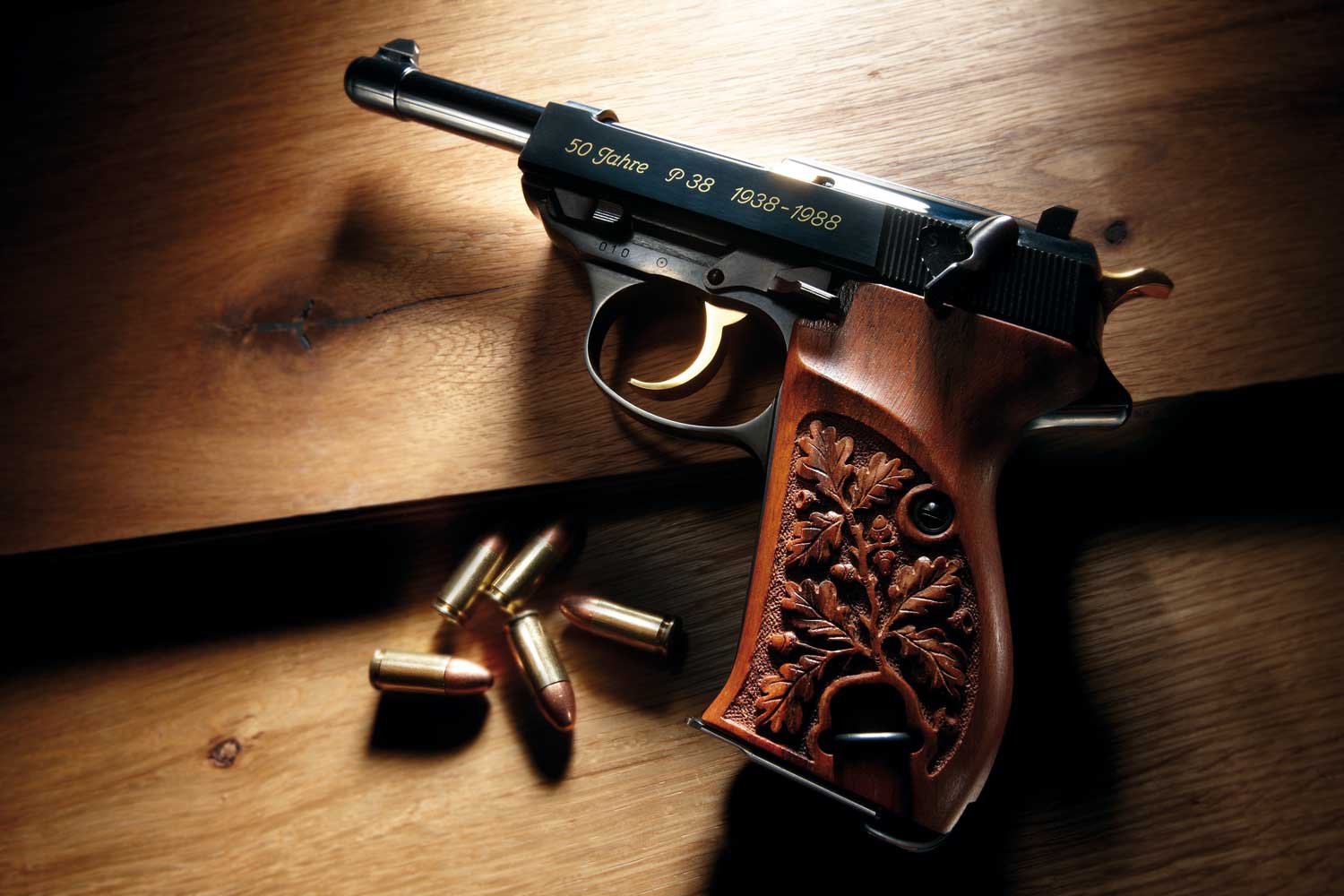

The growing success of Walther with its PP, PPK and its military pistol, the P38 (9mm Parabellum), was soon overshadowed by the rise of the Third Reich and the dark chapter in German history that ensued. On September 1, 1939, Germany attacked Poland and the world was once again plunged into war. In early April of 1945, the first Allied troops to arrive at the Walther factory in Zella-Mehlis were a vanguard of General Patton’s 3rd U.S. Army. By July the Thuringia region fell under Soviet control and soon thereafter the Walther factories were demolished by explosives. It seemed that the final chapter of the company’s history had been written.

Fritz Walther and his family were able to resettle in the western sector in the town of Heidenheim but escaped with little other than a few personal possessions. At the end of the war, Germany lay in rubble, hardly a place to restart a business of any kind, let alone a manufacturing facility. Fritz Walther, though, once again had a trick up his sleeve.

Among the items he had been able to take from his home was a metal moneybox, his family’s “nest egg,” along with some blueprints of his company’s adding machines. With these, Walther was able in 1947 to start a one-room factory in Heidenhem to produce a small adding machine, the product that had helped keep Walther afloat after the first World War.

Remarkably, within less than five years the company was housed in a new three-story factory and was exporting its line of adding machines to more than 40 countries.

At this point it would have been easy for Fritz Walther to sit back and smell the roses but he was committed to getting Walther back into the business his father had started in 1886. In the years right after World War II, however, the Western allies had banned the manufacture of firearms in Germany, but the clever Fritz saw an open side street: the manufacture of air rifles and air pistols. The company’s expertise in precision engineering once again proved valuable in the design and production of innovative and highly accurate air guns.

Workers at Walther’s plant in Ulm, Germany, prepare slides for production.

As the economy of the new German Republic began to revive in the post-war years, Walther built a new factory in Ulm and produced a line of air rifles and pistols that found a strong market among recreational and competitive shooters. To this day, Walther offers several lines of technically advanced air rifles and pistols that are commonly used in international and Olympic competitions.

While Walther could not build firearms in Germany, the company could license manufacturing in other countries. Fritz Walther contracted with the French firm, Manurhim, which began production of PP and PPK pistols in 1952. Again, it was a shrewd move and one that, in good measure, brought Walther back into the firearms business. Over the next few decades, Manurhim would build more than 1.2 million examples of this classic series of pistols under the Walther name.

The P38 is another famous Walther pistol.

As restrictions on firearms manufacturing were loosened, Walther began producing firearms in the homeland, first with a revised version of their famed P38 for the German military and, in the years ahead, a return to the civilian market. The company once again flourished but the hard years had taken a toll on Fritz Walther who, after a heart attack in 1965, died in 1966 at the age of 77.

An engineer who never forgot his father’s maxim, “Do everything so well that nobody else can do it better,” Fritz Walther also understood that always “doing something” was just as important in keeping his family’s gunmaking business alive through difficult and turbulent times.

In 1993 Walther merged with the German firm Umarex and quickly began a new era of expansion and product innovation, especially with the introduction of the Walther P99 in 1996 followed by their PPQ series and the PPS, a modern version of the legendary PPK. Several years ago Walther established its United States headquarters and a service center for U.S. customers in Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Through the years, Fritz Walther, like James Bond, often found himself in dire circumstances, a predicament from which there seemed to be no escape. Yet neither Bond nor Walther ever gave up and, with a good measure of pluck and ingenuity, they always managed to pull through and live another day. Reaffirming, in each case, the old adage that the true measure of success is not so much in what we accomplish, but what we overcome.