We had a voodoo sheriff when I was coming up. He and Pappy were best friends. Ed McTeer turned to the black arts to extract confessions and make himself bullet-proof. It served him well one night when a desperado cut loose in some dim-lit island juke joint, five shots at close range and never cut a hair. When the solicitor tried to add attempted murder to the charges pending, Ed McTeer would have no part of it.

“There was no murder attempted,” the sheriff famously testified in court, “because there was no murder possible. It was just like he was shooting at me from a mile away.”

And then added even more famously: “I would stand the length of this court room and let a man with a pistol shoot at me all day long.”

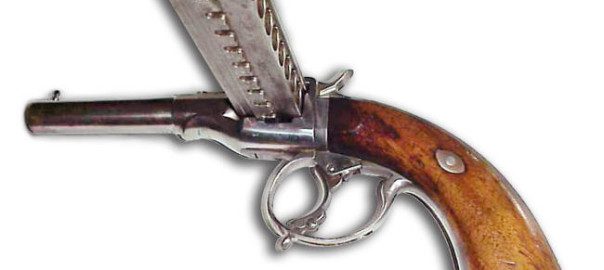

The sheriff had a collection of old cap-and-ball Colts, the most extensive outside the Colt factory, folks said, picked up from pawnshops and felons over the years. Pappy had one the sheriff did not own, an 1862 .36 Police, factory-converted to .36 rimfire about 1880. You might have seen one, with a stagecoach robbery scene engraved around the cylinder, where you can’t get the whole drama unless you pull the hammer to half cock and spin the cylinder with your thumb. The sheriff tried to beat Pappy out of it for years, to no avail.

But December 7, 1941 changed the negotiations. Pappy was in the National Guard, coast defense artillery outfit, and when the Japs bombed Pearl Harbor, he knew he was going, but did not know where or when.

Turned out it was right quick—Saipan, Tinian and Okinawa, the worst of it, knee deep in mud and blood. But he didn’t know that when the radio blared the news when he was unloading a truck of salvaged brick and he took his Colt conversion to the voodoo sheriff.

The collection, complete to his satisfaction, the sheriff sold and bought a plantation.

Pappy came away with a 1903 Springfield, circa 1921, and several bandoliers of ammo, old as the rifle, growing corrosion like fine green hair. Because he knew military ammo would be impossible to find once the war cranked up, Pappy insisted the sheriff throw in something he could afford to shoot for practice. So, the sheriff came up with a Remington .22 Sportsmaster, circa 1936, still in the factory box.

Good choice. Pappy earned an Expert Rifleman badge in Officer’s Candidate School. He gave that .22 to my cousin the day before he shipped out.

I was born nine months, almost to the day, after Pappy’s return, and I grew up shooting the ’03 Springfield. The mossy old ammo first, so dubious there was generally a second or more between the click and the boom, if indeed there was any boom at all.

“Watch out Sonny,” Pappy cautioned when I went to cycle a dud. “If that thing goes off with the bolt unlocked, it’ll put you in a glass eye and a gold front.”

Meaning it could knock out my teeth.

When I shot up what would shoot, Pappy brought home a can full of linked belt machine gun ammo, armor-piercing, with every fifth round a tracer, most likely courtesy of the South Carolina National Guard, but I asked no questions.

If there was anything left of the bore, which by then resembled a miniature of the Dakota Badlands, those tracers took care of it. But oh, what fun I had, lighting up the night.

I always harbored a notion to re-barrel it someday but someday never came.

But 40 years before the partition of Pappy’s scant assets, on my 14th birthday, my cousin gave me that Remington .22, the voodoo sheriff’s gun, the one that sharpened Pappy’s eye for his Expert Rifleman badge, and thus it was spared the divvy. I taught my own children with it and it put squirrels and cottontails on the table when there were more lean years than a body could hardly stand. Eighty-odd years after it was built, it will still put bullets in the same ragged hole, all day long, 50 yards, 100 yards, don’t matter.