A mid-summer fly fishing trip turns into an impromptu elk hunt. There before me stood 80 elk or more, the nearest ones no more than 70 yards away.

I love hunting elk! And these elk clearly needed hunting. There were four of them—three cows and one young bull, his half-developed antlers lush with velvet and glowing softly in a rich russet gold. They were grazing cautiously a full thousand yards up the mountain and completely unaware of my presence as I fished Poso Creek, their tawny bodies and broad ivory rump patches glimmering in the warm summer sun.

I watched as they stepped one-by-one from around the eastern slopes of the long, heavily wooded spur that separated us, already formulating some loose strategy as to how they might be approached.

I’m going to need to get very close to them, I thought. I wasn’t properly equipped for any sort of long reaching shot, for the only lens I had was a 28-70mm variable zoom, having deliberately chosen it earlier that morning in anticipation of the close-up stream photographs I anticipated shooting while fly fishing this pristine, high-country trout stream. It was a fine and trusted old lens, but even at its most powerful setting it yielded less than a one-and-a-half-power telephoto capability. So my approach to these elk would need to be flawless.

The first 800 yards should be fairly easy, I thought, for I could use the long, thickly wooded spur that lay between them and me for cover. Beyond that, it promised to get tricky. But the breezes were drifting in from the east and flowing westward across the mountain away from the elk, and I knew that if I could get to that island of dark timber downwind I should be able to top out relatively close to them on the far side of the spur.

So I stashed my fly rod in the high meadow grass, marked it with my white bandana, and headed off up the mountain.

It took less than 20 minutes to reach the near edge of the timber, all the while making sure the wind hadn’t shifted.

I lost sight of the four elk as soon as I’d begun climbing, but I figured I was now within a hundred yards of them. The wind was still good, and I began quartering up through the woods in their direction.

The plan was to stay in the dark timber just below the crest of the spur for as long as I could manage, hoping to get within a hundred yards or so before topping out above them. But the cover was now beginning to thin, and I dropped to the ground and low-crawled the final few feet to the top. And there they were—much closer than I’d anticipated and still grazing deliberately.

They had evidently been feeding toward me as I’d been working toward them and were barely 60 yards distant. And instead of the four elk I had initially seen from below, there were actually seven of them, all cow and calves—except of course for the one young bull with the still-developing antlers. Oh, I shot three or four photos, but the angles weren’t right and there were still too many low hanging branches between them and me. So I dropped back behind the crest and began circling away from them—the plan being to move 40 or 50 yards to the west and then slip up and over the crest once more and down to the fringes of the timber and let them graze toward me.

And so I made the move, climbing once more to the top, then easing downslope as quietly as I could, my vision focused entirely on the ground immediately in front of me. Finally, less than ten yards inside the thick timber and still enveloped in shadow, I looked up and my jaw dropped.

There before me in the broad, sloping meadow stood 80 elk or more—cows, calves and a couple of young spikes and juvenile raghorn bulls, the nearest ones no more than 70 yards away.

And none of them had a clue I was there.

For two or three minutes I photographed those elk, carefully shifting side to side, searching for the proper angles and openings through the trees, hoping they wouldn’t detect the whisper of the camera’s electronic shutter as I selectively fired frame after frame. I did the best I could, but knew it wasn’t good enough, for there was still too much brush between them and me.

There was only one thing left to try.

I rose from the ground and began inching through the dark timber toward them, camera raised, framing and focusing and refocusing as I ghosted ever closer to the outer edge of the trees, until I couldn’t remain hidden any longer and discretely stepped from the shadows.

It seemed the entire universe abruptly shifted its collective gaze in my direction as every elk on the side of that mountain suddenly turned its scrutiny on me, and for a moment they all stood frozen in utter shock and disbelief.

All, that is, but one.

That single young bull I had initially spotted from the creek a thousand yards below was standing broadside 80 yards to the east as I stepped into the open, and it was he who made the first move.

Across the slope he flew, charging between me and the rest of what he clearly considered to be his herd before turning and driving them up the mountain. He weaved side to side below them as he urged them away until he eventually melded into their midst, and for a moment I lowered the camera to simply watch the whole spectacle.

Never had I seen such a sight nor heard such thunder of hooves, at least not this close, and I raised an open hand to wish them well. They moved as a single unit, one extended mass of russet red bodies and glowing ivory rumps spread across the side of the mountain and tearing away upward, and again I raised my camera to record their final flight as they neared the dark timber above. But then, just as the leading edge of the herd began to approach the fringes of safety, something changed dramatically.

I first picked him up him through the viewfinder—that lone young bull with the half-grown antlers, not at all certain what I was seeing. At first he seemed to be a mere spec, as if he were the point of some long invisible spear or swift spinning arrow flying back down the mountain toward me, splitting the overall herd as it flowed away around him up that long meadow slope.

And on he came, until finally halting 70 yards above me, standing grand and alone against this mortal threat that he perceived to his kind, his head raised and his eyes glaring as though daring me to come any nearer.

I stood as still as I could manage, even lowered my camera and shoulders to him in order to lessen the threat he sensed as my respect and admiration for him flew across that chasm of empty space between us. After all, he was still just a young bull, learning his potential role in life. But God bless him, he was doing instinctively what he’d been made to do, even if he still didn’t quite understand why: taking care of his herd, protecting them as he had once been protected, seeing to their well-being, even at the risk of placing himself between them and what he clearly interpreted as an immense and imminent threat.

Someday, perhaps someday soon, a grand old monarch whose body and antlers and attitude were far more commanding than his own would come along and steal this herd from him, and most likely give him a good thrashing to boot. But there would surely come a time when he would possess a herd of his own, and nothing would dare take it away.

But for now, this herd and this moment were his.

How long we stood there I cannot say.

For time ceased flowing that cool summer morning high on the mountain above Poso Creek as that noble young bull and I stood staring at each other across 70 yards of open meadow, until the rumble of hooves faded to silence and the last of those glistening ivory rumps disappeared into the deep dark timber above.

Only then did we turn our backs on one another and each disappear back into our own separate realms.

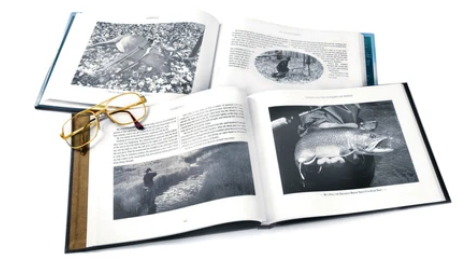

Michael Altizer’s beautiful 240-page tabletop volume of Ramblings: Tales from Three Hemispheres contains 189 lush black-and-white and duotone photographs, paintings and drawings that richly document the author’s contemplative and intimately composed accounts of his hunting and fishing journeys, from Patagonia to Alaska—along with the guns, fly rods, bows and friends with whom he shared the adventures. Signed copy. Buy Now

Michael Altizer’s beautiful 240-page tabletop volume of Ramblings: Tales from Three Hemispheres contains 189 lush black-and-white and duotone photographs, paintings and drawings that richly document the author’s contemplative and intimately composed accounts of his hunting and fishing journeys, from Patagonia to Alaska—along with the guns, fly rods, bows and friends with whom he shared the adventures. Signed copy. Buy Now