Overconfidence and some contempt for bears, born of easy victories cheaply won, led one noted Californian hunter into The Valley of the Shadow.

He emerged content to let his fame rest wholly upon his past record and without ardor for further distinction as a slayer of grizzlies. As mementoes of a fight that has become a classic in the ursine annals of California, John W. Searles, the borax miner of San Bernardino, kept for many years in his office a two-ounce bottle filled with bits of bone and teeth from his own jaw, and a Spencer rifle dented in stock and barrel by the teeth of a grizzly.

On a hunting trip in Kern County, Mr. Searles had a remarkable run of luck and piled three bears in a heap without moving out of his tracks or getting the least sign of fight. It was so easy that he insisted upon going right through the Tehachepi Range and killing all the grizzlies infesting the mountains. He and his party made camp in March 1870, not far from the headquarters of General Beale’s Liebra ranch in the northern part of Los Angeles County.

Romulo Pico was then in charge at the Liebra, and nearly 30 years later, while hunting a notorious bear on the scene of Searles’s adventure, he told me the story of the fight.

Searles was armed with a Spencer repeater but had shot away the ammunition adapted to the rifle, and had been able to procure only some cartridges which fitted the chamber so badly that two blows of the hammer were generally required to explode one of them. Notwithstanding this serious defect of his weapon, Searles had so poor an opinion of the grizzly that he went out alone after the bear several miles from camp. There was some snow on the ground and on the brush, and finding bear tracks, Searles tied his horse and took the trail afoot.

He found a bear lying asleep under the brush and killed it, and while he was standing over the body he heard another bear breaking brush in a thicket not far away. Leaving the dead bear, he took up the trail of its mate and followed until his clothing was soaked with melting snow and the daylight was almost gone.

The bear halted in a dense thicket, and Searles began working his way through the chaparral to stir him up. Of course, the bear was not where his tracks seemed to indicate him to be, and the meeting was sudden and unexpected.

The bear rose within two feet of the hunter and almost behind him. There was neither time nor room to put rifle to shoulder, and Searles swung it around, pointed it by guess, and fired. The ball did little damage, but the powder flash partly blinded the bear, and it came down to all-fours and began pawing at its eyes, giving Searles an opportunity to throw in another cartridge and take fair aim at the head.

If Searles had not forgotten in his excitement the defect of his weapon, the bear fight would have been ended right there. He pulled trigger with deadly aim, but the rifle missed fire. Instead of re-cocking the piece and trying a second snap, he worked the lever, threw in a new cartridge, and pulled the trigger. Again, no explosion. Again he failed to remember the trick of the rifle, and tried a third cartridge, which also missed fire.

Then the bear became interested in the affair and turned upon the hunter at close quarters. Seizing the barrel of the rifle in his jaws, the grizzly wrenched it from Searles’s grasp, threw it aside, and hurled himself bodily upon his foe.

Searles went down beneath the bear. Placing one paw upon his breast, the bear crunched the hunter’s lower jaw between his teeth, tore a mouthful of flesh from his throat, and took a third bite out of his shoulder. Then he rolled the man over, bit into his back, and went away.

The cold Californian night saved the man’s life by freezing the blood that flowed from his wounds and sealing up the torn veins. He was a robust, hardy man, and he pulled himself together and refused to die out there in the brush. With his jaw hanging by shreds, his wind-pipe severed, and his left arm dangling useless, he crawled to his horse, got into the saddle, and rode to camp, whence his companions took him to the Liebra ranch house.

Romulo Pico was sure Searles would die before morning, but he dressed the wounds with the simple skill of the mountaineer who learns some things not taught in books, and tried to make death as little painful as possible. Finding Searles not only alive in the morning but obstinately determined not to submit to the indignity of being killed by a bear, Pico hitched up a team to a ranch wagon and sent him to Los Angeles, a two-days’ journey, where the surgeons consulted over him and proposed all sorts of interesting operations by way of experiment upon a man who was sure to die anyway.

Searles was unable to tell the surgeons what he thought of their schemes for wiring him together, but he indicated his dissent by kicking one of them in the stomach. Then they called in a dentist as an expert on broken jaws, after they had attended to the other damages, and the dentist showed them how to remove the debris and where to patch and sew. They managed to get the shattered piece of human machinery tinkered up in fairly good shape.

The vitality and obstinacy of Searles did the rest, and in a few weeks he was on his feet again and planning prospecting trips to Death Valley—not The Valley of the Shadow through which he had passed, but the gruesome desert of southern California where he found his fortune in borax.

Note: “The Valley of the Shadow” is a chapter in Allen Kelly’s Bears I Have Met—and Others, published in 1903.

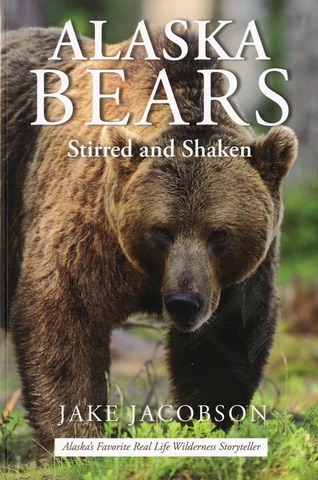

ALASKA BEARS: Stirred and Shaken is a collection of 24 stories describing Jake’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska. Buy Now

ALASKA BEARS: Stirred and Shaken is a collection of 24 stories describing Jake’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska. Buy Now