“There was an earthquake on shore,” Bill said. “A bad one, according to the radio. Ginder thinks we’d better get in before the tsunami hits.”

Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth, whenever it’s a damp, drizzly, mud-season in my soul, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can and pull big fish on a fly rod. I mean really pull them, putting back and heart into it, the long muscles fully in play, breaking rivers of winter-stale sweat under a tropical sun, legs braced and the rod bent to the max, pumping and reeling until I see color at last — the electric blue of sailfish or marlin, the silver flash of a tarpon — and some psychic color comes flooding back into my life, as if in reciprocation.

“If they but knew it,” he wrote in the opening paragraph of Moby Dick, “almost all men in their degree, some time or other, cherish very nearly the same feeling towards the ocean with me.”

Melville called this his “substitute for pistol and ball.”

The Bat Islands rise sharply from the Pacific about 28 miles northwest of the lodge as the frigate bird flies. They’re rough, wet miles in the prevailing seas. Our boat, the Swordfish, was not the fastest, most comfortable, or spacious sport fishermen ever built — a single-screw, 31-foot deep-vee hull not unlike a miniature Rybovich, powered by a 250-horse Volvo turbine — but she’s a legendary Siren at teasing up billfish.

Porpoises crisscrossed our track to the Bats, flirting up alongside to flash their frozen grins, then surging ahead to frolic in our bow waves. From time to time we spotted green turtles, big as manhole covers, bobbing and paddling in the spine-jarring chop. You don’t want to hit one at speed. They can shatter a fiberglass hull as effectively as a mortar shell. But Captain Calin, our skipper, had a sharp eye for such hazards. No problemo.

Surf crashed high on the oddly canted, mustard-yellow rocks of the islands. Squadrons of tijeretas — frigate birds — swung black on their crooked wings against a bright blue sky. Already half a dozen other sport-fishing boats were trolling conventional tackle in random patterns off the Bats, chumming up sailfish with dip nets full of live anchovies. But we were fly fishing — no live bait allowed.

The standard deployment of teasers for sailfish on the fly rod is two bonito bellybaits trolled astern, port and starboard about 50 to 75 yards back, and a single daisy chain of ten hookless, plastic squids trailing in the wake amidships. Most beginners at this game troll too loudly. The ideal engine speed for a single-screwed vessel after billfish is about 700 rpm. When marlin or sailfish rise to the teasers, the skipper slows to 500 or less, mainly to reduce the size of the wake and make the fly more visible when it’s thrown.

The standard deployment of teasers for sailfish on the fly rod is two bonito bellybaits trolled astern, port and starboard about 50 to 75 yards back, and a single daisy chain of ten hookless, plastic squids trailing in the wake amidships. Most beginners at this game troll too loudly. The ideal engine speed for a single-screwed vessel after billfish is about 700 rpm. When marlin or sailfish rise to the teasers, the skipper slows to 500 or less, mainly to reduce the size of the wake and make the fly more visible when it’s thrown.

It’s the mate’s job to spot the sailfish when he first appears , then excite him further by playing a bellybait back to him. He allows him to mouth the hookless bait, get a taste, then artfully plays the delectable morsel into casting range. While the sail’s appetite alarm is clanging like a fire bell, its wild eyes big as softballs, the mate “disappears” the bait by whisking it forward and quickly reeling up.

Meanwhile, the “on-deck” angler takes his position in one corner of the sternsheets and readies his gear.

I was the man on deck.

I was fishing a 9-foot, 12-weight Orvis rod, loaded with a shooting head, level line, and a few hundred yards of 30-pound backing. The leader tested 16 pounds. At Joe’s suggestion I’d stripped about 20 feet of line off the big DXR reel — the amount I’d probably have to cast — and coiled it carefully in a plastic bucket at my side. A couple of inches of water in the bucket would keep the line slick and tangle-free at the moment of truth, and the bucket itself would act as a stripping basket, preventing my nervous feet from tangling in the line-coils as they played out when a fish hooked up — a potentially embarrassing situation, as in “Man overboard!”

Eppridge had built the fly, a variant on classic designs originated by Harry Kime and Dr. Webster Robinson, the pioneers of West Coast saltwater fly-rodding for billfish.

“I call it the Frank Perdue Special,” Epp said. “It’s just chicken feathers and Ethafoam tied on a 6/0 Mustad hook.”

But Epp had carefully carved and tapered the Ethafoam body, glued eyeballs on it with irises that actually rolled, and then, for ultra-realism, added garish gill slots with a red Magic Marker.

“There he is,” Joe said quietly.

Brownish-green and big around as a sawlog, the first sailfish of the day suddenly materialized behind the starboard bellybait. Curpin, our veteran mate, dropped the bait back to him and danced it enticingly, then swept it forward as if in escape. The sail was on it in an instant, slashing at the bait with Erroll Flynn-like cuts of its bill. He lit up as if someone had thrown a switch — bright, electric-blue stripes igniting the ultramarine water. Curpin teased him closer.

Bill and Joe brought in the daisy chain and the other bait. Curpin glanced at me and grinned, then disappeared the bellybait.

“Now!” Joe said . . .

I flipped the Perdue Special to the spot where the bait had been. The dark-blue dorsal was weaving from side to side in quick, nervous, searching maneuvers. Where is that damned thing?

I popped the fly once, twice . . .

He saw it and pounced.

I kept the rod tip pointed at him and, when he turned, struck him hard with my line hand — pow, pow, pow — pulling directly back on the fly line in short, sharp pops. I could actually feel the hook bite home. Sails almost always jump at the sting of the hook, and with the rod tip low, I’d already bowed to his inevitable jump. What’s more, if I’d struck him by raising the rod tip as most anglers instinctively do, I’d have been in a poor position to exert any further leverage on him.

So far so good.

But I reckoned without his catlike speed. He erupted from the water not 15 feet away, a big, strong fish climbing endlessly toward the sky, gill plates rattling, that slim, spiky bill flailing like a sabre, one big black eye locked on mine — water flew everywhere. Awed, I held on to the fly line just a nanosecond too long.

It felt like I’d grabbed a live wire.

Line burns smart.

When I brought him alongside the boat 20 minutes later, after two dozen jumps and a run that peeled nearly 400 yards off the reel, my lower back was aching, my wrists and forearms were stiff and I’d sweated a gallon. My line-burnt hand still stung. But I never felt happier. Curpin grabbed the bill and worked the Perdue Special free, and we hoisted the 125-pound fish into the stern sheets for the traditional “grin and grab” photos. Back in the water a minute later, he was still strong. He plunged away into the depths from which he’d risen.

Over the next few days, we all caught and released plenty of sailfish. Eppridge boated a 110-pounder in just nine minutes flat on his 13-foot Sage rod and a Billy Pate marlin reel that spools 600 yards of backing. Each dawn we’d be awakened by the hooting of howler monkeys in the flowering trees around the lodge. Breakfast was hearty: eggs, bacon, crisp home-baked hard-rolls, rich Costa Rican coffee. Then we’d pound out to the Bats and play with sails till the sun swung low. Home again, after a cool shower and couple of pina coladas, we dined on local fish, rock lobster, or barbequed pork, then swapped fishing yarns till bedtime. I can think of no finer way to drive off the spleen and regulate the circulation. But there was more to come….

At 9 a.m. on July 28, 1968, Crater A of the five-cratered Volcán Arenal blew its top, killing the whole town of Pueblo Nuevo and all 600 inhabitants. The gases it expelled reached 2,000 degrees Centigrade. Cows in the vicinity were cooked on one side, but remained alive on the other (temporarily at least). Early in the 1970s another crater popped a “bolus,” a kind of volcanic mortar round of superheated lava. A Land Rover carrying four vulcanologists happened to be motoring along the unpaved road toward the town of La Fortuna. The bolus landed squarely on top of it, oxidizing the Rover and its passengers in an instant. Phhht! Like that. When Peter Gorinsky, our fishing guide at Aremil, told us these stories, I began to wonder if volcanoes weren’t sentient as well as destructive. If so, the Roman god Vulcan is a hell of a shot with a mortar.

We fished Lake Arenal for an afternoon, evening, and the following morning under placid blue skies in refreshingly cool mountain air, catching gaudy, strong, slab-sided guapote, a.k.a. “rainbow bass” — close relatives of South America’s peacock bass — on small, bright poppers and light fly rods, cruising the lake and watching for rises, plugging the weedy shoreline with gratifying results. But every 20 minutes or so, Vulcan spoke. His voice was as loud as a 16-inch naval broadside. It raised the pucker factor a tad. Just when we’d forgotten him, concentrating on dropping the tiny poppers in the path of feeding fish, Ka-boom! There he was again, nudging our shoulders. But it kept us alert, on our toes and if at night we dreamed of sudden, scalding death, I’m sure it made better persons of us in the long run.

We were in for more of the Pacific Rim’s rock-and-roll action at Casa Mar, though we didn’t know it when we arrived. Casa Mar is one of the world’s finest snook and tarpon camps. Located just south of the Nicaraguan border, it was then owned and operated by Bill Barnes, a short, bandy-legged fellow from Maryland who has followed the angling action wherever it’s hottest in the Western Hemisphere. Billy runs the place like he would his own home: tiny, tidy, thatch-roofed cabins with overhead fans. A sprawling, fragrantly scented dining room. A well-stocked tackle shop. An open bar where the rum flows as freely as the fish tales, and nobody frowns when you pour another or light up a smoke. Billy’s gundogs — German shorthairs and English pointers — lope the grounds and poke their meaty noses up from beneath the tablecloths at dinner. When the fish are in, it couldn’t be better.

The terremoto hit about 4 pm. It registered 7.4 on the Richter Scale. I’d been fishing outside the barra since lunchtime on that Monday, hooking and jumping and sometimes boating tarpon of 60 to 125 pounds. Pods of them came rolling through like silvery freight cars. All you had to do was cast the 12-weight line out there with a big, bushy, orange-and-black Harry Kime streamer attached, strip it in a few times, and wham —they were skyborne. All afternoon we’d been following the clouds of birds — tijeretas, tropic birds, ospreys — and catching, then releasing, the tarpon beneath them. I stopped for a minute to replace a frayed tippet, and when I looked up the birds were gone.

The terremoto hit about 4 pm. It registered 7.4 on the Richter Scale. I’d been fishing outside the barra since lunchtime on that Monday, hooking and jumping and sometimes boating tarpon of 60 to 125 pounds. Pods of them came rolling through like silvery freight cars. All you had to do was cast the 12-weight line out there with a big, bushy, orange-and-black Harry Kime streamer attached, strip it in a few times, and wham —they were skyborne. All afternoon we’d been following the clouds of birds — tijeretas, tropic birds, ospreys — and catching, then releasing, the tarpon beneath them. I stopped for a minute to replace a frayed tippet, and when I looked up the birds were gone.

“Qué pasa?” I asked Tony, my boatman.

He shrugged. “Beats me.”

The Caribbean sloshed dark and glutinous around us. Not a tarpon rolled as far as we could see. I threw and stripped for another 20 minutes, but not even a jack crevalle hit. The tarpon guides curse jack crevalle, and they are indeed the plague of these waters — strong, tenacious fish that grab your fly with the ferocity of tarpon but never jump and take nearly as long to subdue. A Casa Mar boat came squirting towards us. It was Eppridge and his guide, Ginder.

“There was an earthquake on shore,” Bill said. “A bad one, according to the radio. Ginder thinks we’d better get in before the tsunami hits.”

At first I thought he was kidding — Eppridge is a notorious jokester — but I saw he was dead serious. We raced the tsunami ashore at full throttle over the treacherous barra, where a boat had broached the previous year and a couple of fishermen were scoffed by the ubiquitous bull sharks that prowl these waters, and beat it narrowly — a five-foot comber that smashed docks at the Rio Colorado Lodge and totally rearranged the sandbars that guard the river entrance. When we wheeled into the docks at Casa Mar, all hands breathed a sigh of relief. In the dining room, shattered plates littered the floor and the fish-mounts on the wall hung cockeyed. A waitress sat weeping quietly in one comer of the kitchen. Billy Barnes strutted in.

“The damn thing threw me out of bed,” he said, grinning. “I was taking a nap, and when I looked out the window the trees were swaying. All the dogs were howling like mad and the monkeys were screaming. I thought the lodge was going to fall down.” He laughed uproariously. “How do you like that? Always something new in Costa Rica.”

We went down to the rivermouth next morning to survey the damage. It was hot, airless, with great, greasy swells crosshatching the boca. A big hunk of wharf from upriver was adrift, blocking the passage to sea. “I saw it come ashore about six o’clock last night,” my guide Tony said. “Damn glad we got in ahead of it. It’s the first time I ever saw a wave cause a corriente — a current — in the rivermouth.”

At the seaport of Limon well south of us, and only about 25 miles from the quake’s epicenter, the tsunami had sucked all the water out of the harbor, leaving the fishing fleet high and dry, then came crashing back in to smash docks, swamp boats and disrupt public services like water and power. The quake itself had destroyed bridges on the only highway to Limon from San Jose. In Limon alone, the death toll was placed at 23. Electricity was out throughout the country. Some terremoto.

When I got home to Vermont a few days later there was a foot of fresh snow on the ground. Down at the general store I bumped into a local meat fisherman.

“Where’d you get that tan?” he asked suspiciously.

“Down in the tropics ,” I said. “Fly fishing.”

“You mean like you fish for them tiny brook trout around here?”

“Yep.”

“Catch anything?”

“A few.”

“Do them tropical fish eat any good?”

“Don’t know,” I said. “I threw them all back.”

He smirked. Damn-fool flatlander.

“Say, Bob,” he asked slyly. “How deep did you have to wade to catch them tropical fish?”

“Deep enough,” I told him.

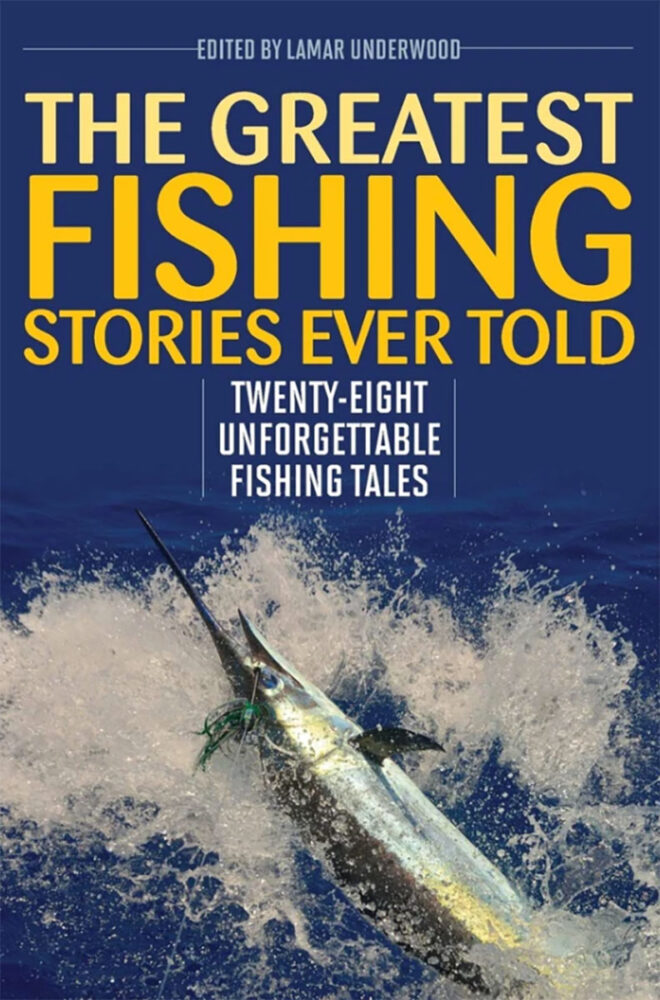

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish. Buy Now

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish. Buy Now