William Marcus Cathey was a son of North Carolina’s Great Smokies and a man who lived what for most of us could only be a dream—a life devoted primarily to hunting and fishing.

Born in 1871, most of his life was spent on Indian Creek in what is now the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP). The general area formed the setting for many of his legendary sporting feats as a sportsman, and in his case the often overused word “legendary” is richly deserved. Acknowledged by contemporaries as being in a class by himself as a fly fisherman, he also personally killed 57 bears and was a member of parties accounting for hundreds more. Similarly masterful when it came to the calling skills and woodsmanship needed to deal with wild turkeys, it is unlikely that the region has ever produced a finer all-around outdoorsman.

While collectively mountain folks of his era revered the sanctity of work, and while Cathey never shirked arduous undertakings, there can be no denying that he lived 70-plus years doing pretty much what he enjoyed. He never married, never held a steady job over an extended period of time, and never shed his deeply ingrained sense of independence. Over the course of his life he held a variety of jobs connected with logging, was in the employ of George Vanderbilt during construction of the famed Biltmore House, spent some time as a surveyor’s assistant when the GSMNP was created, and frequently guided visiting “sports.” Much of his logging work involved timber herding, a particularly dangerous job in a generally dangerous profession. Timber herders broke up log jams and sometimes even rode logs downstream, sure-footed as bobcats, after the gates of splash dams were opened. The job required agility and athleticism along with a high level of fitness. Those were precisely the attributes which allowed Mark to wade cold streams hour after hour or follow dogs hot on the trail of a bear over terrain impassible for all but the hardiest of men.

My father knew Cathey, who was a distant cousin, well and recalled a poignant moment in the final year of Uncle Mark’s life when heart problems had made it impossible for the old sportsman to cast to rising trout the way he once had. Still, learning that Dad and a friend were headed out for a day of fishing, Cathey asked if he could come along for the ride. They readily agreed. Mark’s sadness at being able to do nothing except watch was palpable, but as he said to my father, “I’ve had my days, and they’ve been mighty good ones.”

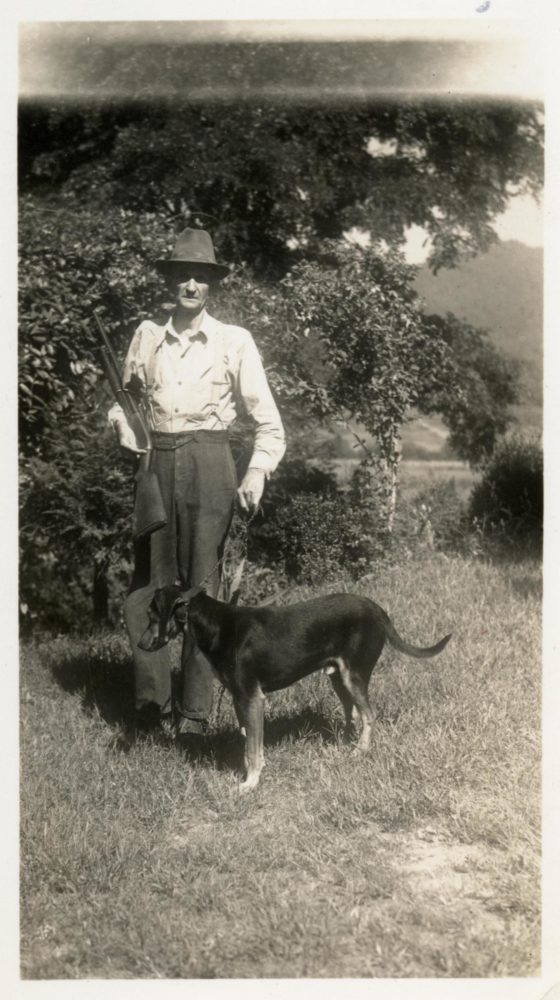

Those days encompassed decades of outdoor endeavor. Lean and lanky, Cathey had a body tailor-made for the hardships of being afield or astream in the Smokies. His long legs ate up mile after mile of Smokies terrain in indefatigable fashion. Another distinctive feature was his voice. His high-pitched manner of talking and distinctive brogue harkened straight back to Elizabethan days. One description of his speech pattern suggested he “sounded like W. C. Fields with an Irish accent.” Another characteristic those who knew him personally repeatedly mentioned was the piercing nature of his deep-set eyes. “It was like a hawk looking at you,” one friend noted, “and Mark could spot a squirrel high up in a tree or the flash of a trout like no one I’ve ever known.”

His frequent companion and kindred spirit in Deep Creek days stretching over the decades was Sam Hunnicutt, and in that worthy’s quaint book, Twenty Years Hunting and Fishing in the Great Smokies, one chapter after another opens with the words: “A trip made by me and Mark Cathey.” Whether alone, with Hunnicutt and others, or accompanied by dudes he was guiding, Cathey made hunting and fishing trips without number while becoming a regional legend. Even now, some four score years since his death, mention the name Mark Cathey on his native heath and sportsmen immediately take notice.

Today he is primarily remembered as the dean of Appalachian fly fishermen, thanks to being a pioneer in use of the dry fly as well as for a technique he called “the dance of the dry fly.” The latter was highly innovative, employing a method which decades later members of the Eastern angling establishment would claim to originate as “fishing the dry fly as a living insect.” Relying on a long rod and relatively little line while allowing only the fly to touch the water, Cathey shook his rod hand to impart motion, making the fly jump and skip like an insect trying to escape the surface film.

There can be no doubt about his effectiveness. Whenever a party of sportsmen went into the backcountry, they could rely on Cathey to provide a mess of trout in short order. In a bit of pardonable exaggeration, one frequent camping companion described his skill in this fashion. “We’d make camp and get a pot of water on for coffee. Before the water could come to a boil Mark would be back with enough trout to feed five hungry men.”

While Cathey is best remembered as an angler, he was a sportsman for all seasons. At the age of 12 his father gave him a muzzleloading rifle with strict admonition to squeeze the trigger only when he had a sure shot. Cathey became a superb marksman, partly because he realized that with the black powder gun he only had one opportunity. Even later in life when he hunted with breech-loading guns, his shooting ability remained exceptional. Perhaps the best indication of that skill is that most of the turkeys he killed were taken with a rifle.

Hunting anything from bushytails to bears, bobcats to ‘coons, tickled Mark’s fancy. “Uncle Mark” (the honorific he carried in later life) was as gifted a storyteller as he was a sportsman. Droll, dry, and quick, Cathey was ever alert for a prank. Unsurprisingly, as a noted trickster he became the victim of considerable innocent mischief in his own right. Legions of stories are linked to his life, and there’s arguably no finer way to appreciate the world in which he lived than through a sampling of those episodes.

Once, in the early years of the GSMNP, a local ranger was talking to a visiting angler preparing to set off up the creek. He happened to look up and see Cathey coming down the trail. His wet overalls indicated he had finished fishing and was hiking out. Knowing Cathey wouldn’t have stopped fishing until he had creeled the 10 trout constituting a legal limit, the ranger asked Cathey to show the visitor his catch. Mark gladly obliged, lifting one fine trout after another from his basket. He counted as he went, and to the ranger’s dismay, the total was 11 fish. Realizing that Cathey would never intentionally exceed the limit, he said: “Oh, you just miscounted.”

Cathey would have none of it. He painstakingly counted the trout again then said: “Well, damn me, I’ve catched over the limit. Just write me a ticket and let’s be done with it.” He refused to leave until the ranger reluctantly obliged.

Humble as he was honest, Cathey nonetheless realized he possessed exceptional angling prowess. Once, when asked about his abilities, he replied: “I’ve been accused of being the best fisherman in these mountains. I ain’t denying it.”

Many enduring Cathey tales revolve around his penetrating wit. Once he met a local fisherman who had spent several hours astream and only had two small trout to show for his efforts. The two began chatting and the man asked Mark: “How many have you caught?”

“My creel’s empty,” Cathey promptly replied. The frustrated angler sagely nodded in understanding, saying the lack of success didn’t surprise him. Mark just grinned, then added, “But the only reason it’s empty is that I ain’t commenced fishing yet.”

The best known of all Cathey stories involved a wealthy Yankee sport who hired Mark as a fishing guide. The greenhorn showed up looking like a sporting-goods catalog cover model, adorned in chest waders, a brightly colored shirt, and a hat holding flies of every hue in the rainbow. He sported an expensive bamboo rod equipped with the finest reel available. Most striking of all his paraphernalia, however, was a massive Bowie knife hanging from a sheath on his wader belt.

The client proved to be a study in ineptitude. He couldn’t cast, kept Cathey busy retrieving flies from trees, and complained constantly about the dearth of trout. Finally, whining “there are no fish here and I’ve come hundreds of miles for no reason,” he provoked a response from Cathey.

The staunch mountain man said: “Let me hold that fancy rod and I’ll show you.” In the next quarter hour Uncle Mark caught one fine trout after another, proving there were plenty of fish present although doing nothing to improve guide-client relations.

Matters deteriorated as the day progressed, and by mid-afternoon Cathey’s quotient of patience was exhausted. At that juncture the visiting angler, in a moment of sheer happenstance, hooked a small trout that clearly needed removal from the gene pool. In great excitement he reeled it in—all the way to the tip of his nine-foot rod. Highly agitated as he watched the minnow-sized fish flop out of reach, he turned to Cathey and asked: “What do I do now?”

In his inimitable fashion, Uncle Mark drawled: “Well, I reckon you better pull out that big Bowie knife, climb your fancy pole, and stob it to death.”

Over much of his life Mark was a convivial soul who enjoyed a dram or two of liquid corn at day’s end. Once, when he had for a time sworn off John Barleycorn, he came into a hunting cabin well after dark. Soaked to the bone from mixed rain and snow showers, he could not resist when fellow hunter “Poley” Bryson offered him a belt of soothing syrup. Mark drank it down, savored the tanglefoot’s burn, and remarked: “Poley, I believe I’ll have me another nip. I’m just naturally colder than I thought I was.”

On another occasion the same cabin was the setting for my personal favorite among myriad Cathey tales. It involved his introduction to raisin bran cereal, which had just come on the market. A member of the fishing party had brought some along on the trip and carried a jar of milk to go with it. The first morning in camp the man poured himself a bowl then politely asked: “Mark, would you like to try some of this here new bran cereal?” Cathey nodded assent and polished it off with apparent relish. However, while eating he frequently paused, turned from the table, and spat. This caused some raised eyebrows, but no one uttered a word about the unusual behavior. Once Cathey finished the cereal, the man who had furnished it asked: “Mark, what do you think of that new cereal?”

Uncle Mark’s replied, “Well, it’s right tasty but, by gad, I fear the rats have been at it.”

On yet another trip, Cathey and several others were staying in a ramshackle cabin known as the Bryson Place. Mark had just gotten a new set of false teeth, and after a hearty supper of trout and taters, together with a salad of “kilt” ramps and branch lettuce, members of the group indulged in a few nips of corn squeezin’s. Mark was the first to call it a night, and after crawling into his bunk he placed his dentures on an exposed two-by-four beam. Shortly thereafter another member of the party, also equipped with false teeth, did the same.

Soon both men were snoring, and a compatriot quietly switched their dentures. Next morning both arose, and each inserted the other man’s dentures. Amazingly, they ate breakfast that way, and somehow the rest of the group managed to keep straight faces. Once the pair finished their meal, they arose from the table and headed outside the cabin. Quietly following, their mischievous compatriots discovered the men on opposite sides of the cabin, each using his pocket knife in an effort to reshape dentures that had somehow become distinctly uncomfortable overnight.

Mark never married and in 1929 his eight siblings conveyed the old family home and adjoining property on Indian Creek to him for the sum of one dollar in gratitude for his devoted care of their mother in her declining years. Sadly, just a few years later the National Park Service seized the old family home and its accompanying acreage. For that little piece of mountain paradise, including the house, a section of stream embracing a lovely fishing pool known as the Cathey Hole, and with spectacular Indian Creek Falls situated just downstream, he received the pitifully small sum of $1,800.

As a result, the final decade of Mark’s life found him rootless. No longer could he hunt most of his familiar haunts, although trout fishing was allowed in the newly created GSMNP. Nor did he have a permanent place of abode, and according to those who knew him best, “no one seemed to know exactly where Uncle Mark lived.” His health was also in decline. Arduous years of covering 20 or more miles a day fighting through rhododendron hells and climbing up and down ridges had taken their toll.

With his health failing and his sporting days but a warm memory, Mark spent increasing amounts of time in downtown Bryson City. There he often held court at the site on the town square variously known as Loafer’s Glory or, more crudely, Dead Pecker Corner. Invariably his inimitable ability to spin a yarn drew a crowd. His death came on a late autumn afternoon while in the squirrel woods, and no sportsman could wish for a more fitting demise.

His sister had told him she was baking sweet potatoes for supper, and that inspired Mark to go after a mess of squirrels to accompany them. He set out for a nearby grove of mast-laden hickories where he knew the bushytails would be working. Accompanying him was Mark’s beloved canine companion, a mountain cur he described as being “pure pizen” on bushytails. As light gave way to night, and as suppertime came and went, Mark failed to show up. Near midnight a hastily organized search party found Cathey at the foot of a gnarled old hickory tree, a brace of squirrels by his side with his faithful dog curled up in his master’s lap.

Cathey was buried in the Bryson City Cemetery atop School House Hill. Hundreds of fellow sportsmen and friends turned out on a brilliant Indian Summer day to bid him a fond farewell. Rev. W. Herbert Brown, a local Baptist minister who had converted Uncle Mark only a few weeks before, wrote a fitting final chapter to the life of an iconic sportsman with as powerful and poignant an epitaph as you will likely ever encounter:

MARK CATHEY

1871-1944

Beloved Hunter and Fisherman,

Was himself caught by the

Gospel hook just before the

Season closed for good.

As one glances up after reading those words, it is to look northward toward the Deep Creek and Indian Creek drainages, with stair-stepping ridges mounting in the distance toward the misty blue majesty of Clingmans Dome. This rugged country was the place Cathey knew and loved best, and as one reflects on his world—a sporting world that has traveled the same road to oblivion as the American chestnut–it is to realize that here was a man who walked paths of wonder. He may not have held regular jobs, and there were even those inclined to call him trifling. Yet to reflect on his easygoing existence is to look back with envy and no small measure of admiration.

As is true of many other old-time mountain fly fishermen, Mark Cathey figures prominently in Jim Casada’s award-winning book, Fly Fishing in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park: An Insider’s Guide to a Pursuit of Passion. The 450-page, lavishly illustrated book is available in both paperbound ($24.95) and hardbound ($37.50) formats. Postage in either case is $5. Orders through www.jimcasadaoutdoors.com or from the author, c/o 1250 Yorkdale Drive, Rock Hill, SC 29730.