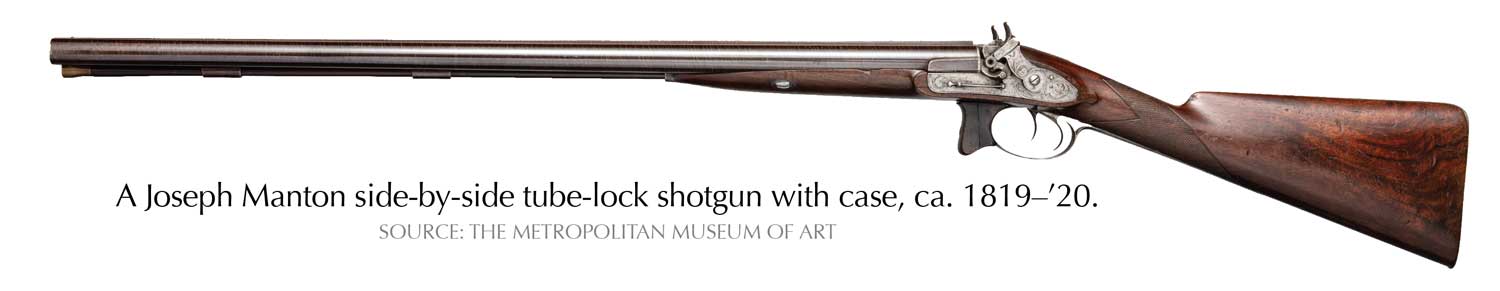

The double shotgun took its form when Joseph Manton (1766 – 1835) put two shotgun barrels side by side with their independent flint locks. Manton spent lots of his time working on explosive ordinance for the British Army, but we fondly remember him for establishing the form of our double guns. Perhaps by coincidence the Holland & Holland factory in London overlooks the cemetery in which Manton is interred. It might be safe to say that Joseph Manton was the father of the London gun trade as James Purdey, Thomas Boss, William Greener, Charles Lancaster and William Moore all worked for Manton at one time or another.

Manton’s guns were all muzzleloaders, but when breechloading shotguns came into being in the later 19th century, an entire microcosm of the shooting of driven game came into being. Here it was common to shoot a true pair of shotguns from Purdey’s, Holland & Holland, Churchill or others from a long list of gunmakers either in London or Birmingham. Ruled by strict guidelines the late Robert Churchill wrote in his book Game Shooting that to “pot another man’s bird” would cause you to “blot your copybook.” In other words, not be invited back. If you’re interested, Isabel Colgate penned a novel called The Shooting Party that was later made into a movie starring James Mason that delves into the morays of the Edwardian Era. That period of time, about 1880 until the beginning of World War I, was so named for King Edward VII. Prior to succeeding his mother Queen Victoria to the throne, he shot hither, thither and yon on his estate at Sandringham and elsewhere, coincidentally driving many into bankruptcy keeping up with “Bertie” as his mother called him. Driven shooting continued after the Great War and World War II and is still fairly popular today, with spaces for well-heeled visiting guns from other nations.

Side-by-sides were the gun and mostly you had a loader who would take your fired gun, recharge it with cartridges from his leather cartridge bag, and pass it back while you shot the other of the pair at passing birds. The top shot of the day could take two birds in front, change guns and, with the loader ducking down, two birds in back as they passed over. Robert Churchill in Game Shooting describes a situation where two of the finest “guns” of the day had a flock of eight partridge come over and they killed the lot with neither man taking what would be considered the other’s bird. I doubt Bubba and Clem would be so courteous today!

Side-by-side guns had several advantages, one being that they open with a smaller arc making ejecting the fired cartridges and reloading easier for the crouching loader. Probably more important is that when broken open they are completely safe, but probably the best characteristic is the balance of a fine double.

Two stocks for a true pair of doubles from the same fletch of walnut.

Part of the intrigue of double guns are those that are bespoken—i.e. made to order for a specific person. Holland & Holland, Purdeys and others are best known today for these fine guns where every aspect is tailored to the buyer. The shooter is measured, fitted and the gun built for him or her alone. That’s not to say that you or I couldn’t pick up someone’s bespoke shotgun and kill a boat load of game, but it is made precisely to shoot where that shooter looks and the barrels choked specifically for his or her type of shooting, be it driven in the Dales of Yorkshire, walking up in the cornfields of South Dakota or decoying ducks in Arkansas’s flooded timber.

When driven shooting is on the docket, a “true pair” is made using an extra-large fletch of the finest walnut that is sawn in half providing near identical grain in the finished stocks. Too, every item is the same save for a small numeral “1” or “2” on the actions and top rib of the barrels to delineate which is which. There are also “matched” pairs that are one gun being made and then, at a later time, a second gun made to match the first. Finally, there is a composed pair that are two guns perhaps by the same maker but not necessarily the same that possess the feel and balance of each other.

Some feel that the broad expanse of a side-by-side’s barrels distract the shooter’s eye, and that’s true if the shooter “sights” a shotgun like a rifle, but then a bespoke shotgun would do him or her no good, because our eyes are the sights of a shotgun and if it shoots where we look the bird will fall. Today the over/under has pretty much eclipsed the side-by-side. It’s the darling of clay shooters and a quick browse of many gun catalogs shows heavier over/unders for clays and plenty of light-weight guns for the field.

The year 1909 was especially notable for shotgunners as it was then when John Robertson, who had succeeded the Boss family to the ownership of the London firm of Boss & Co., introduced the Boss over/under shotgun. Boasting a single trigger (double-trigger over/unders were made and can still be had on a bespoke gun) and a unique locking system made the Boss an icon. At The Antique Arms Show in Las Vegas my wife shouldered an over/under she spotted and said, “I really like this gun!” to which I responded, “You should!” It was an $80,000 Boss 20-gauge! They are lovely shotguns, somewhat rare and a pathfinder of what was to come.

Prior to 1931 when the Browning Superposed over/under was first cataloged by Browning, bespoke British-made guns were the norm and at the price of a minor duke’s ransom. John Moses Browning’s quest was to produce an over/under shotgun at a “cost not prohibitive” to buyers. When first cataloged by Browning in the U.S., the standard-grade Superposed sold for $107.50. The Superposed was John Browning’s last firearm and he, in fact, died at his bench in the Fabrique Nationale factory in Liege, Belgium, on Thanksgiving Day 1926 as he worked out the details of the Superposed.

The trigger from a DT 10 showing 1. the trigger/hammer sear engagement, 2. the leaf-style hammer spring and 3. the inertia block that joins the trigger with the hammer sear.

Browning’s work was then taken up by his son Val who put the finishing touches on the Superposed including an innovative “Twin-Single Trigger.” Using the traditional double triggers, when you pulled the front trigger the bottom barrel fired and a second pull of the same trigger then fired the top barrel; pull the back trigger and the top barrel followed by the bottom barrel fired in sequence. The mechanism worked fairly well, but was highly complicated and the devil to adjust if it got out of whack. The Twin Single soon gave way to Val Browning’s “Inertia -Shift” trigger that used recoil to move the trigger’s sear to the hammer sear of the unfired barrel, and versions of it have become common throughout the double-gun world.

Remington Model 32 showing the sliding hood that locks the barrels to the action.

The Browning Superposed was not alone in the U. S. as the Remington Model 32 came along in 1932. Its initial price was $75 and that jumped to $82.50 two months later. The Superposed was manufactured by Fabrique Nationale in Liege, Belgium, but the Model 32 was wholly made by Remington in Ilion, New York.

Three pairs of over/under barrels. Top: The Browning Superposed showing the deep action and slot for the Purdey sliding underbolt. Middle: The Blaser F 16 that uses a split underbolt that allows the barrels to sit lower in the action. Bottom: Perazzi barrels showing the low-lying engagement on the sides of the bottom barrel into which two bolts projecting from the breechface lock giving the gun a slim profile. All are time-proven locking systems.

The most common method of holding the barrels shut on any double gun is the Purdey sliding underbolt. It lies at the bottom of the action and engages a slot cut below the bottom barrel or the monobloc. As solid a bolting system as you’d like, it does take up space in the action making it fairly thick top to bottom. The Boss uses two projecting bolts that engage two cuts or holes near the midpoint of the barrels, thus taking the bolting from the bottom of the action to provide a very slim profile. This style of bolting moves the lower barrel down into the action so that the recoil is directed straight back into the heavy muscles of the shoulder and away from the shooter’s face. Today, Perazzi, Fabri, Beretta and others use this system.

Beretta FT 10 showing its Greener cross-bolt locking system. The steel bar impinges against the two mid top-barrel lugs providing a strong lockup.

Another locking system is the Remington 32, 3200 and Krieghoff 32 and K80 method that employs a sliding breech cover that locks the barrels from the top while making for a slim-profiled action. There are other top-locking bolts such as the Greener crossbolt used on Beretta’s DT 11 that employs a hardened bar of steel that, when the action is closed, slides across two projections from the barrels holding them tight. Another version of this is the rotating cylinder used on the A. H. Fox doubles that, when the action is closed, rotates into a square cut on an extension of the barrels holding the gun tightly closed.

Proponents of over/unders point to its “single sighting plane” as opposed to the broader view down the side-by-side’s barrels. Again, if you’re looking at the sighting plane, save the shell, you’re going to miss. There are, however, other advantages to the over/under.

For starters, all side-by-sides shoot low because of barrel flex, which is compensated for by the configuration of the butt stock. Often called barrel flip, pretty much any rifle’s or shotgun’s barrel flexes from the forces of the fired shot. A shotgun is a light, facile gun meant to be moved, so its barrels must be light, so we must compensate for the flex. If you look at a construction site, you’ll notice I-beams used as structural supports. The barrels of an over/under are much the same—they’re built like an I-beam and hence flex is far less than a side-by-side. It’s a feature that has made them the darlings of clay sport shooters.

One of the drawbacks of an over/under is its stacked barrels where there can be wind resistance, be it slight, but shooting in a heavy wind can slow the swing of an over/under. Many competition guns have the side ribs connecting the two barrels “ventilated” with a series of gracefully shaped openings. Remington’s Model 32, the later 3200 and Krieghoff take this a step farther by separating the barrels for their entire lengths save for the chamber ends secured in the monobloc and via a hanger at the muzzle; the ultimate barrel-cooling design. Keeping the barrels as cool as possible is beneficial during summer’s heat when shooting a number of shells in fast succession such as in trap where the built-up heat can cause a mirage or shimmer that confuses the sight picture, so keeping the barrels cool is important in clay target shooting, but not so much for hunters save perhaps a hot corner in an Argentine dove field.

Carrying an over/under in the field is about the same as a side-by-side except the barrels opening at a wider arc, which can be a problem in a duck blind or goose pit. That’s easily overcome by standing and putting the gun outside the pit or blind loading with the barrels level or slightly down, then closing the action by bringing the stock to the barrels and finally retreating into the blind with the gun vertical.

Either style of shotgun, side-by-side or over/under, offers the ability to quickly select a different choke. However, nothing is as efficient as double triggers. The front trigger traditionally fires the right or bottom barrel and the rear trigger the left or top. I recall a driven red-legged partridge shoot south of Toledo, Spain, where writers were treated to gun-factory tours. A colleague had several redlegs fly over his stand. He fired a single shot then bellowed, “Damned double triggers!” However, learning to use double triggers takes nearly no time at all, but is best done with clays, not in the field.

When my wife and I celebrated our 40th anniversary in London, we made the rounds of the gunmakers including Holland & Holland’s factory and shooting grounds. When it came to picking a gun to shoot, our instructor said, “We have a selection of Berettas,” to which I answered, “We live across the Potomac River from the Beretta headquarters. We want to shoot Hollands.” My wife got to shoot a lovely 20-gauge Royal over/under—£65,000 on the hoof, you do the math—and within a station or two on their sporting clays course she had them down pat.

For my money, other than double triggers, the Krieghoff and Blaser barrel selector is the easiest and fastest to use. It’s a little hook-like projection right in front of the trigger that pushed left fires the bottom barrel first and pulled right by a right-handed shooter fires the top barrel first. Least convenient is the Italian-style sliding selector in the safety, which makes moving the selector at a pheasant’s flush difficult. The Perazzi style is OK, but the gun must first be on safe to move the selector—not bad in the field, but on a sporting clays course it’s a nuisance because of the possibility of leaving the gun on safe when you call for a bird.

Both side-by-sides and over/unders will put game in the bag or Xs on a scorecard, so it all comes down to personal preference, but quality is important. Some bargain doubles and over/unders with the swing characteristics of a railroad tie are best used as tomato stakes. By the same token, a quality side-by-side or over/under will last, with some care, decades.

Side-by-side or over/under? Take your pick, they’re both good.

This article originally appeared in the 2021 Guns & Hunting issue of Sporting Classics magazine.