The best of them did advertising work during the period, and many of them derived a major part of their income from book, calendar, magazine advertising and other commercial work. However, most did not want to be known as commercial artists and there was a reluctance to sign some of this work.

During this period mail was still somewhat novel, even in the early 1900s, and it carried impact. When a letter was removed from the mailbox it was not at once torn open, but rather carried back to the house, anticipation mounting with each hurried step, and only after all the family members had gathered was the top crease carefully slit, the letter removed, and its message read.

When a letter was removed from the mailbox it was not at once torn open, but rather carried back to the house, anticipation mounting with each hurried step, and only after all the family members had gathered was the top crease carefully slit, the letter removed, and its message read.

It was inevitable that sharp minds in advertising would eventually utilize the mail as an effective promotional media. Radio and motion pictures had not yet exerted their awesome influence on the consumer, and young companies were anxious to extol the virtues of their products to a growing population. So, in addition to the posters, calendars and other works, some of the premier artists of the day did designs for envelopes. Unfortunately, many of those fine talents, by virtue of doing that type of work, were dubbed as illustrators and degraded in the art community. Many of the best artists of the day did this “calendar art” for the money, but often refused to attach their names to the work lest their eminence as “fine art” painters be tarnished.

No one knows exactly where the idea of illustrated envelopes came from, but during the War Between the States, illustrated envelopes were used to carry patriotic messages. Perhaps that was the beginning.

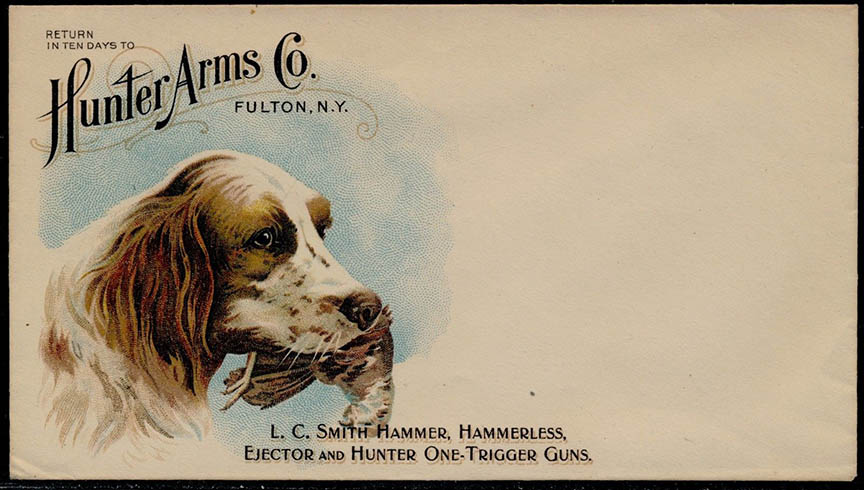

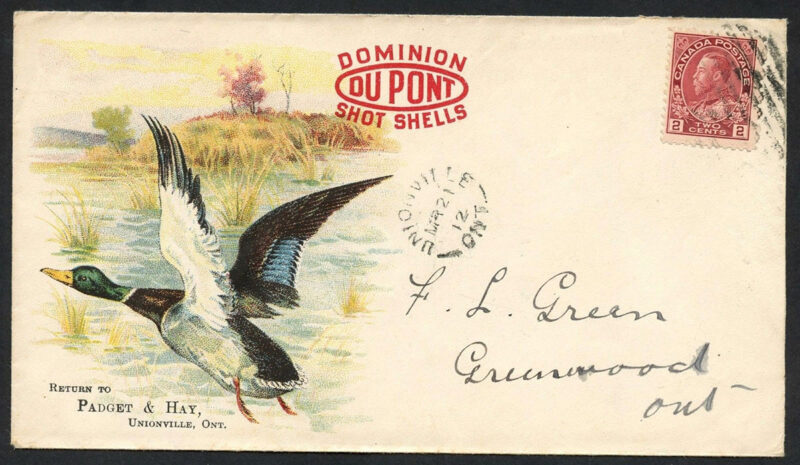

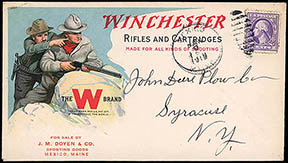

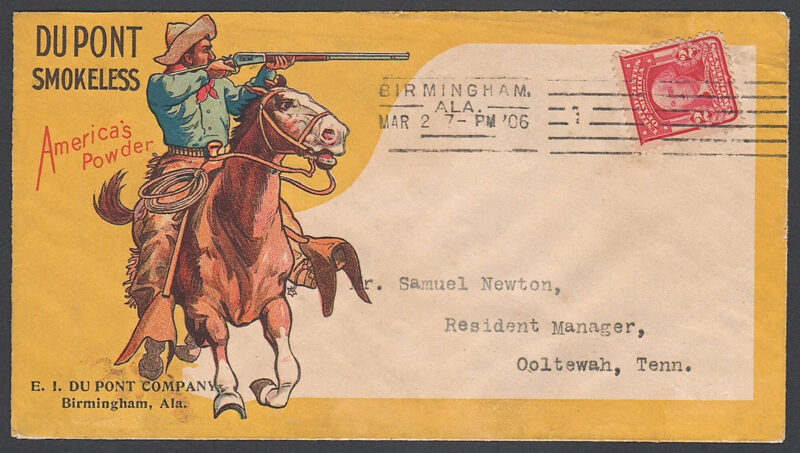

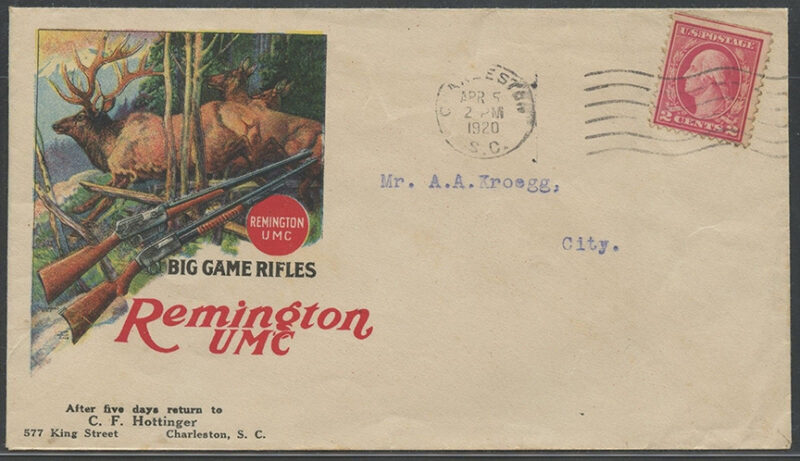

Firearm, ammunition and gunpowder companies were prolific users of promotional envelopes, but products as diverse as padlocks and bicycles, seed corn, buggy tops and sewing thread were advertised on mailing envelopes. All major and many lesser firearm companies used them, including Winchester, Remington, Ithaca, Hunter Arms Co., Stevens, Savage, Colt, Parker, Marlin, Lefever and Iver Johnson. Ammunition and powder companies that used promotional envelopes include Remington, UMC, Peters, U.S. Cartridge Co., Hercules, Laflin and Rand, DuPont, E. C Schultze, Atlas, Hazard and Sycamore.

In philatelic jargon, envelopes are called “covers,” and early gun covers are for the most part exquisite renditions that stir the imagination and kindle adventurous fires. They are absolute jewels of turn-of-the-century firearms advertising. The envelopes depict big game, upland birds, waterfowl, hunting dogs and even Indian chiefs in full ceremonial dress. Scenes of a Northwoods trapper confronting a wolf pack with his Winchester lever-action, of a tense stalk for Dall sheep in the mountains, and of pleasing hunting camp scenes with a full meat pole in the background are sufficient to cause wanderlust fever in even the most complacent nimrod.

For example, “Winchester” was almost always printed in red and the large red “W” trademark graced most of Winchester’s covers.

The sporting whims of women are catered to as well and properly attired young lasses are shown approaching setters on point and triumphantly standing at a trap station. The space on the back side of the covers was not to be wasted and typically carried print and illustrations extolling some of the finer points of the product. The back side of a 1903 envelope is covered with full color illustrations of many of the company’s cartridges and shotshells.

Aim was taken at the international firearm and ammunition market. Some rare covers sport foreign stamps and postmarks, but the message, although from an American company, was printed in the appropriate foreign language.

The earliest gun covers date back to the 1880s and those typically bear a monochrome illustration of a rifle or shotgun, usually printed in red, black, blue or brown. As the art of lithography progressed, bi-color covers were produced and eventually the stunning multi-color examples of the early 1900s. However, many of the companies stuck to some basic color schemes. For example, “Winchester” was almost always printed in red and the large red “W” trademark graced most of Winchester’s covers.

The artist is never credited on these envelopes, but commonly the name of the lithographer does occur in small print in a corner of the illustration. It is interesting to speculate who some of the artists were. Certainly, some of them were well-known and company-commissioned specifically for the work, as were the artists for many of the calendars and gun posters. Other of the illustrations must have come from the stock supplies of the printers, and one of their sales catalogues would be a valuable research tool today if it could be located. A list of lithographers known to have produced gun covers includes: ., Cincinnati, OH; Steinbach, New Haven, CT; Faatz, Lestershire, NY; F. E. Getty (no address); The Knapp Co. Lithographers, NY; Bartlett and Co., NY; and Dietzer-Sale Litho Co., Buffalo, NY.

Although advertising covers are among the rarest of firearm collectibles, it still seems fortuitous that as many of these small bits of paper have survived the years.

Interestingly, advertising covers did not just come from the manufacturing company. Rather they were distributed in bulk to jobbers and retailers all over the country. Usually the return address of the hardware or sporting goods store was preprinted on the envelope. These distributors were encouraged to use them for all of their personal and business needs.

Although advertising covers are among the rarest of firearm collectibles, it still seems fortuitous that as many of these small bits of paper have survived the years. This may reflect the propensity of people from that era to be more inclined to save their correspondence, or perhaps they were just as attracted to these fascinating envelopes as we are. Preservation has also been enhanced by the practice that many small companies and stores had of filing their letters as a matter of business record.

Fishing tackle companies entered the arena of mass marketing too late for the heyday of advertising envelopes. There is one memorable cover from Al Foss, however, that shows a bass leaping after one of their pork rind minnows. The return address puns that, “if he doesn’t catch it in five days, return to Al Foss-Mfg. of Fishing Tackle-Cleveland, Ohio.”

Firearm advertising envelopes, like calendars and posters, are colorful and exhibit considerable artistic merit. They have the additional advantage of being easier to store or display. As do gun catalogues, covers contain a wealth of technical information for the firearms historian.

Firearm advertising envelopes, like calendars and posters, are colorful and exhibit considerable artistic merit.

Some covers are rarer than others, but all are scarce and in high demand. The value of a gun cover is determined by essentially the same parameters that affect the price of most other types of sporting memorabilia. Age, condition, aesthetic appeal and rarity are most important. A used cover that has actually been sent through the mail has more value than one that was never addressed, but it is not the stamp itself that affects price. These were typically low denomination regular postal issues and quite common. It is the presence of the stamp, orchestrated with other trappings on the cover such as the address, postmark and cancellation, that lends historical significance to the piece and affects price. Such information serves to authenticate the cover and establishes point of origin, destination and date of the cover. If the letter happens to be addressed to a famous hunter, sportsman, showman, exhibition shooter or other person of note, it carries special charisma.

Stamp brokers and philatelic auctions are the most dependable sources of firearm advertising covers, however, the monetary investment required when buying from dealers is becoming substantial. Most serious collectors don’t bat an eye at paying $200 and up for a moderately scarce cover in good condition [Editor’s note: 1983 dollars]. Still, the investment seems secure. Both good firearm and good philatelic material are continuing to escalate in value in the current tangibles market which is less than booming with the strong dollar.

Scarcity of old gun covers today belies the fact that many of them were once printed in large quantities. Presumably many were destroyed upon receipt or have otherwise succumbed to the ravages of time. Still, there must exist numerous examples not yet in the hands of dealers or collectors waiting to be discovered. The search for these treasures should lead to ledges formed by the eaves in an attic, correspondence bins of old hardware stores, drawers of roll topped desks and under display counters in long-standing sporting goods stores. Trunks and old safes in back storerooms should not be neglected. Undoubtedly, many are still tucked amidst the ledger books of defunct businesses.

The modern blitzkrieg of junk mail conceived through the eye of a camera and mass-printed on cheap, glossy paper now inundates our postal boxes. We hastily discard reams of this bulk mail every year, angered at the imposition it has caused. We hastily discard reams of this bulk mail every year, angered at the imposition it has caused. No longer does a single letter in an envelope decorated with a hunting scene tug at our inner yearnings for the love of outdoor sport and kindle fond memories of our days afield.

Let the light shine! This stained glass art hanging shows its true colors when backlit with natural sunlight. Printed with fade resistant inks. 20″H x 14″W. Ready to hang with provided chain. Produced exclusively by Wild Wings. Designed, printed and assembled in the USA. Buy Now

Let the light shine! This stained glass art hanging shows its true colors when backlit with natural sunlight. Printed with fade resistant inks. 20″H x 14″W. Ready to hang with provided chain. Produced exclusively by Wild Wings. Designed, printed and assembled in the USA. Buy Now