Painter Rod Crossman, considered one of the greatest sporting artists of our time, connects us to holy outdoor places that span generations. This is how we are transported into the wildlight.

Think about your greatest fishing memory, the one that, like a fine Scottish whisky, only keeps getting better with age. You know the one I am talking about; it hovers in your mind as an eternal perfect day. No sound attached, only a certain quality of light. You know you can’t physically re-inhabit it because the essence is fleeting, though it is precisely the vision’s elusiveness that makes you want to reach out and touch it even more.

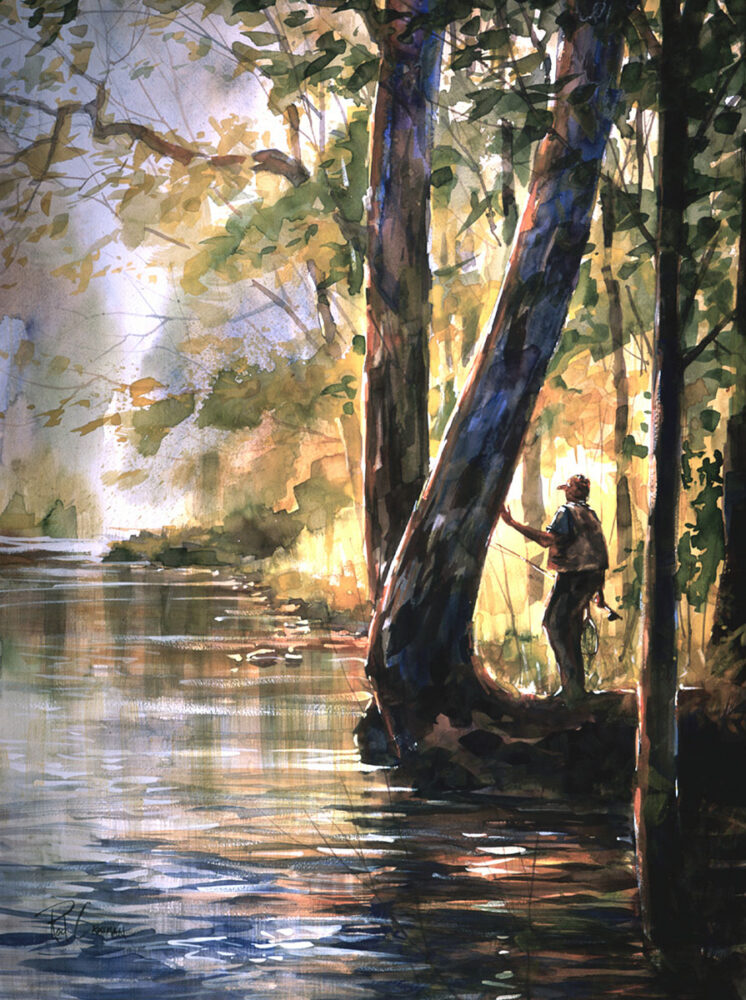

The Perch by Rod Crossman

It’s been said that in a Rod Crossman painting, the viewer’s eye can see into the sweet hereafter and back. To understand the impact Crossman’s art has on those of us who grow up hunting and fishing, all it takes to grasp is listening to a devoted Crossman collector. Not long ago, I had the pleasure of doing that, visiting with a guy named Jeff Lengbehn.

Langbehn is a retired environmental attorney lauded for many different conservation endeavors. A hunter for 55 years, he’s loved stalking ruffed grouse and waterfowl with a succession of good dogs and one of his cherished side-by-sides.

Enthusiastically, he’ll tell you he considers Crossman to be among the best sporting artists of our time. He remembers the exact moment, four decades ago, when he encountered his first Crossman watercolor painting. “I was attending an art fair in Griffith, Indiana,” he says, “and as I strolled past, the sight of it stopped me in my tracks.”

Many different art writers and collectors have tried to adequately describe the effect Crossman’s artworks have—the moods and feelings that well up inside. Calling his scenes “mystical” or “magical” doesn’t bring justice; what they do is trigger a certain kind of emotion not easily explained.

Crossman, revered for his own angling prowess, is affable and unpretentious, soft-spoken yet uncannily insightful. He always is pondering his surroundings with tenacious, sensitive curiosity.

“My painting style is about capturing the moment just before or just after an experience that changed me in some profound way. The emotion, and memory of that time. It may have been something that opened my eyes to a thing I’d never noticed or filled me with awe or woke me to a different kind of reality,” he says. The experience of being transported into the wild light.

Walking Out by Rod Crossman

Like visitations made by people in our past that happen during slumber, he believes the spiritual presence of shared places and moments continues in nature. “As humans, we all share similar emotions and some experiences,” he says. “Persistent memories keep coming back when our senses are touched by something familiar. It might be a smell, a color, a reflection in the water, the sound of the wind in the trees. In my work, I’m trying to evoke those things. I think that’s why in some ways what I’m seeking is a dreamlike or ethereal quality.”

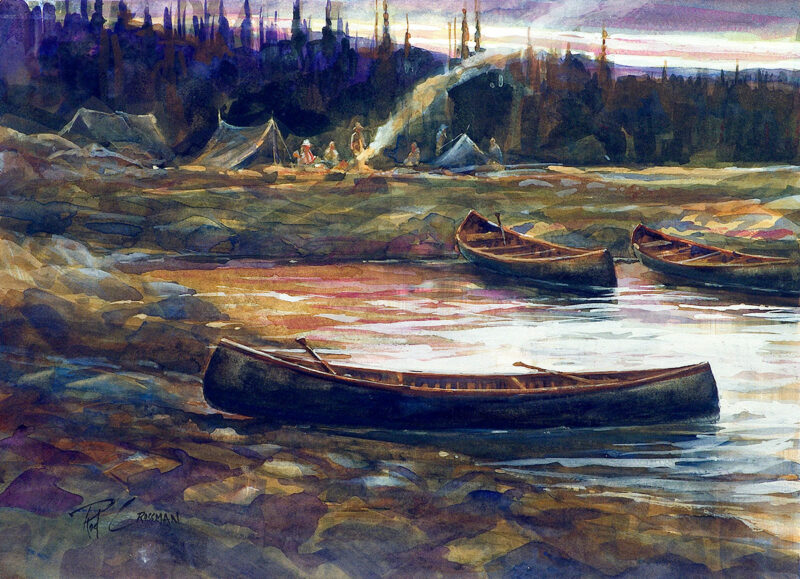

Base Camp by Rod Crossman

The sensation, and Crossman’s exquisite mastery of watercolor, are evident in the works Basecamp and Trout on the Bend. Truth be told, he paints the way a philosopher thinks. His works have been likened to a cross between those of Philip R. Goodwin, the god of classic wilderness “predicament scenes” and the waterfowl and game hunting works by Winslow Homer and the late Chet Reneson.

Crossman was born in South Dakota, raised in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York where, as a boy, he pursued bass, pike and panfish with bait and spinning rods. Eventually he moved to the Hoosier State where he taught art to high school students and then became a college art professor. It’s not his style to be the Robin Williams character in the movie Dead Poet’s Society but with similar encouragement he would entreat his students to experience the world before trying to communicate it, because that is what makes art authentic.

Trout on the Bend by Rod Crossman

Often, Crossman would escape to favorite rivers and woodlots in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan that once were haunted by writers such as Ernest Hemingway and the late novelist Jim Harrison, best known for his novella, Legends of the Fall.

I first conversed with Crossman more than three decades ago, just about the time he started painting covers for Gray’s Sporting Journal and other outdoor magazines, and before Chuck Weschler started using some of Crossman’s images to illustrate the well-written pieces in Sporting Classics. As Weschler would say, adding in a Crossman illustration to a compelling hunting tale always made it read more profoundly.

Mayfly Bluegill by Rod Crossman

With Mayfly Bluegill, Crossman demonstrates his sophisticated contemporary instincts with design and composition. With self-deprecation, he readily admits that his passion for fly fishing “denied my two boys any chance at a normal childhood but fortunately they inherited my love for moving water, trout and the outdoors.” Along the way, the Crossman clan had a stream of bird dogs that became members of the family—an English setter, English pointer and several Labrador retrievers. (His dog portraits, too, possess their own pizzazz).

“Rod is the kind of sportsman who every child would hope their dad would be,” Langbehn said.

It’s unclear whether Crossman’s experiences in the field fly-fishing or carrying a shotgun have more informed his novel aesthetic in painting— or whether painting has enabled him to better communicate the sensations of being outdoors that all sporting people seek and revel in when they are not doing it.

Quail by Rod Crossman

For Langbehn, original Crossmans have been touchstones in his life, beginning with his 30th birthday when he received an artwork as a gift. He had mentioned to family and friends how mesmerized he was by Crossman’s ethereal handling of wildlife and water scenes. In that mile marker year, his parents gave him the first piece of fine art he ever owned—a Crossman portrayal of two anglers in a canoe fly-fishing with the background retreating into muted diaphanous light.

Langbehn was left stupefied and still gets kind of choked up recalling the parental gesture—and how it became the impetus for a long friendship his family has enjoyed with the artist that extends across generations. A few years later, on the day Langbehn graduated from law school, his folks marked the occasion with another thoughtful gift—a Crossman depiction of a hard charging moose running up a stream straight toward the viewer.

Pointer Wind by Rod Crossman

Langbehn’s father had been deeply moved by Crossman’s work, and for years he had a painting in his office that gave him solace. After he passed, Langbehn inherited the work and, every time he glances at it, he thinks of his dad and the times they spent together in northern Michigan on a stream (that shall not be named) chasing trout and trying to flush partridge in the woods. “Every time I look at that painting, I think of him—of the times we had together and the thought that art can deliver two different people to the same place.”

In describing where he finds inspiration for the aesthetic effects of his work, Crossman said: “One…I am a wade fisherman. When I’m at least waist deep or more in the water, there is a sense of weightlessness. When the laws of gravity don’t apply any longer, it’s easier to believe in something impossible happening. Hope or hopefulness needs that kind of belief. I guess wading helps me see more clearly and feel more completely a part of the stream, too.”

He also alludes reverentially to the scale of nature and the balming therapeutic impact going afield has—of how it has been a wellspring for euphoria and a cathartic refuge for shedding grief. “Rivers, streams and the creatures that live in them induce such a sense of wonder and awe within me. When we experience awe and wonder it makes everything else around us bigger and ourselves smaller. For me, this is a way to help overcome the cynicism, doubt and fear that so easily creeps into our everyday lives.”

A Pair by Rod Crossman

Over the years, Crossman has, as one of his eccentric habits, gathered rocks—stones of all kinds of geological origin smooth polished by time and river flows. Some of them he has turned into found object sculptures. He believes they exude the essence of time and space. “Our relationship with objects and the meaning they bring to our lives is full of complexity. Why do we collect certain things?” he asks. “Why are some objects so important to us? What are the objects we hold on to saying to us? It seems to me that objects just like our bodies are only temporary things. But the messages, meaning and stories within them transcend time. We see parts of ourselves and others in them and are reminded once more we are not alone.”

While Crossman identifies as a Christian, he says most people he knows feel a divine presence in nature. He quotes Cardinal Emmanuel Suhard who observed, “To be a witness does not consist in engaging in propaganda, nor even in stirring people up, but in being a living mystery. It means to live in such a way that one’s life would not make sense if God did not exist.”

Crossman by Rod Crossman

Not one to judge any person for whichever spiritual path one chooses, Crossman mirthfully enjoys considering ancient myths that have arisen in different cultures. In a few of his paintings, river flies have become translucent fairies lending credence to the notion of enchantment awaiting beyond every river turn.

Some three decades ago, I wrote a profile about Crossman. Back then, there existed a consensus that he was fast-emerging as one of the most talented sporting artists of his generation. Be it portraying evanescent, wending courses of trout water with an angler barely visible in fog, or depictions of hunting waterfowl over marshes, Crossman’s paintings can transport us into deeper reflections on our own favorite places. I have a small Crossman on the wall that I pass by every day and it delivers me, for an instant, to a lake in the North Woods, sitting on a dock with my grandfather at dusk.

I must admit that talking with Crossman and enjoying seeing a steady stream of paintings emerge across most of my adult life has helped change the way I ponder what’s important during treks into the backcountry.

“I believe the invisible things of this world are the eternal and that the visible things are temporary. The selfless things we do for others is how to make the world a better place,” Crossman says. “I’m not holding myself up as a great example of that. In fact, for most of my life I think I’ve been a selfish person. But over the years, I’ve wanted more and more to invest my life in those kinds of eternal things. To teach art students for four decades might be my greatest art accomplishment. Many of them have stayed in touch with me. Many of them are doing amazing things and it makes me so thankful to be a part of it in some small way.”

One Way Over by Rod Crossman

I asked Crossman recently if his impetus for painting had changed given the loss of a few people close to him including his wife? “I’ve been blessed to experience a lifetime of wonderful outdoor memories. A lot of my friends and loved ones are gone now. But when I’m on the stream, the space between this world and the next gets a lot thinner. It puts me in touch with the eternal, which in some ways encourages me to hold the things this world says are important loosely,” he said, then added, “Nowadays I find myself sitting on the bank a lot more than I used to, but that leaves more room for the memories.”

Crossman hopes his paintings will cause some to put down the rifle or fishing gear for a few moments and become more appreciative of what produces exceptional habitat for other creatures to survive. “If we could see the others’ story, if we could see the invisible, it could make the world a better place,” he explained. “This is part of the reason why the world needs art. It helps us see, it opens us to the unseen and eternal parts of ourselves and others. It helps navigate the endless mysteries. I love what one of my favorite writers Richard Rohr says about mystery. “A mystery isn’t something we can’t know; it’s something endlessly knowable.”

“Art exists,” he says, “as a way to restore awe and wonder.” Langbehn, on the day of our conversation, was standing in front of a Crossman that had left his father entranced and inside the frame is a window to a place where both artist and his dad dwell. If we hold people in our memory, he notes, they are never really gone.

This is the perfect gift for a fly fisher who loves a good cocktail with their wild fish stories! To aid the in joy of the journey, mix yourself one of this book’s tasty libations, build your campfire, sit back for some highly entertaining fish stories and lose yourself in the search. The 120-page book features both full-color paintings and photographs. Buy Now

This is the perfect gift for a fly fisher who loves a good cocktail with their wild fish stories! To aid the in joy of the journey, mix yourself one of this book’s tasty libations, build your campfire, sit back for some highly entertaining fish stories and lose yourself in the search. The 120-page book features both full-color paintings and photographs. Buy Now