Autumn arrives early in northern New England. It comes the morning after the last sticky night in August when you climb out from damp sheets and walk barefoot to the porch to hear the loons moaning on the lake. The sky turns pink and the fog rolls in, and it’s cold. Cold—like you haven’t felt since April when you came in from the rain on opening day of turkey season, when the leaves were only yellow pops on wet, bare branches. Your skin shivers, and you feel the earth turning away from the sun.

Soon the birches and maples will cast their leaves onto still pools where the brook trout hide. The salmon will run up the fast part of the rivers and the woodcock will take cover in the edges of the freshly mowed hayfields. The air in the orchards will be thick and sweet as cider. The acorns and beechnuts will fall with loud thuds that you mistake for the footsteps of deer. Dark shapes will lumber through the dark parts of the forest at morning and evening. Moose? You can never tell. The bears will be in the woods and you will follow them, because it is hunting season and you are a hunter.

I arrived in bear camp in early September, and when I walked out of the cabin into the dark morning I saw my breath was swirling in the porchlight. My guide Jack walked over.

“There was a skin of ice on the water bowls,” he said. “I had to crack it so the dogs could drink.”

His lined face came into the light. Without a sound of thanks, he took the mug of coffee and disappeared back to the yard to sort out the hounds. I could hear yelps, smacks and snarls—some from the dogs and others from Jack, who liked to punctuate each whack or tug with a dog’s name pronounced as if it were an expletive.

I never asked Jack his age, but a hard-living 60 seems like a good guess. He had a red nose, brown teeth and had probably been tall before his shoulders started to bow. I never really found out what color his hair was, since he never took off the frayed and stained Red Sox cap. His uniform consisted of green-checked flannel and faded blue Wranglers. If you gave him some fancy camo duds from Underarmour of KUIU, he’d probably just cut them into rags to rub WD-40 on his Ruger Redhawk. The revolver was his self-defense weapon, as much a part of him as the crooked smile and ribald sense of humor. He uses the pistol to give the “coop-dee-grass” to bears in need of a little more killing.

Once the dogs were loaded into the aluminum box on the truck bed, we set out. The cabin was a long, bumpy way from asphalt, so for several miles the truck bounced and squeaked over dirt roads through the woods, the weak headlights cast a small bubble just ahead of the bumper. Deep in a forest of dark firs, I had the sensation of being locked in a submarine—the kind used to explore underwater shipwrecks. It was eerie. I half expected to see one of those ugly fish with a big head and the phosphorescent lanterns dangling over its jaws. For a kid from the suburbs, being this deep in the woods is always claustrophobic.

The tires hit asphalt around the same time as light started shooting over the treetops. We drove for an hour on twisting roads running along misty rivers, past potato fields and through the shriveled husks of old mill towns. We pulled back onto a dirt road in a large tract of forest managed for mixed-use. A silver mist still hung over the trees, with the dinosaur hump of Mt. Katahdin floating on the horizon.

Soon the road branched off into progressively narrower and rougher tracks deeper in the birch and pine forest. The truck had to plow a way through underbrush as branches and saplings scraped the windows and knocked against the doors. The axles and the dogs squealed at every large hole.

The truck rumbled to a small clearing where the trees had all been cut down and left behind. Now they were as white and dry as old bones. Chest-high grasses grew in the spaces between stumps and slashings. Jack got out first.

“I’m going down to check the camera at the bait site to see if we have a bear that’s worth running. You can stay here if you want.”

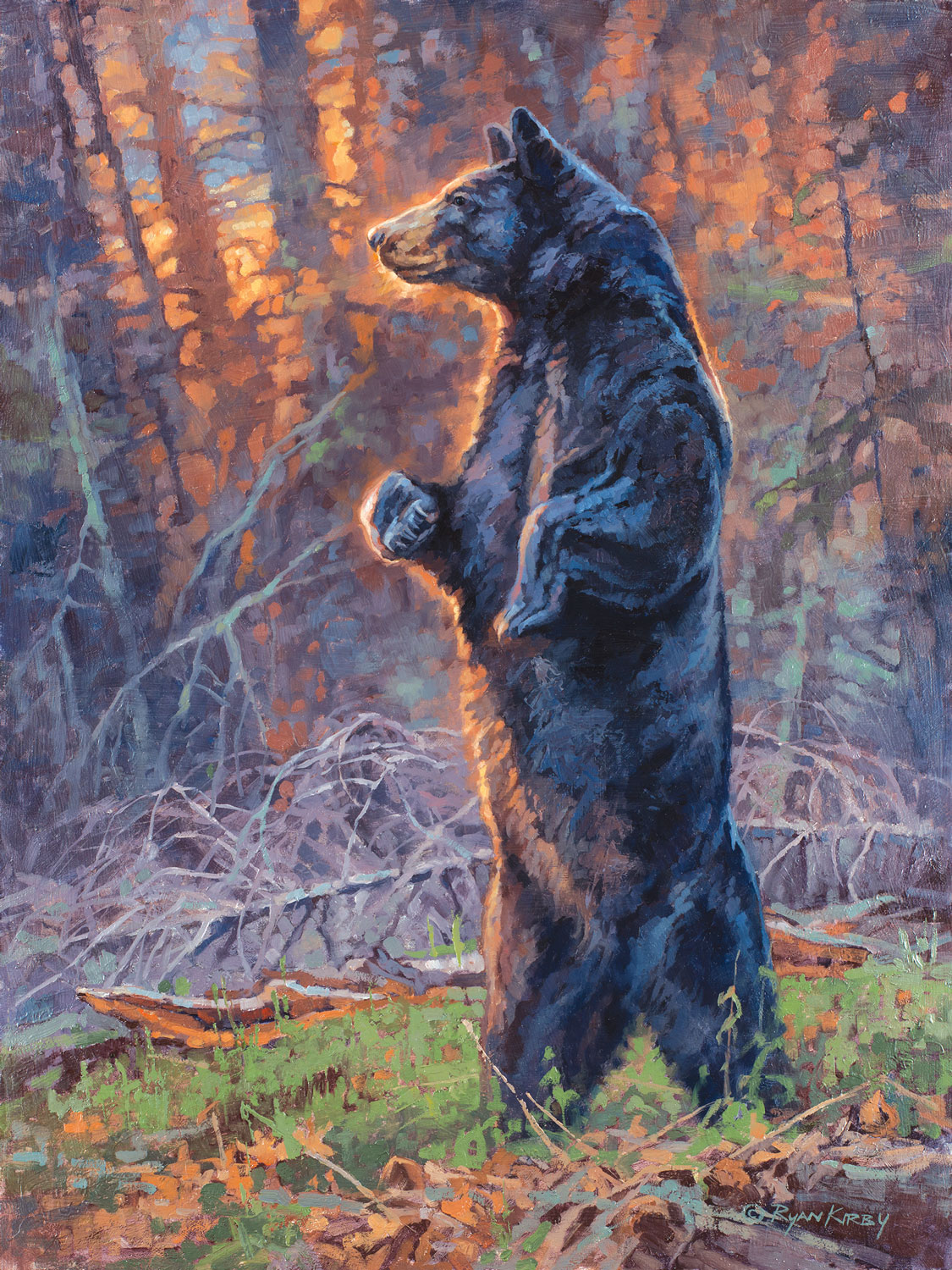

Standing Tall by Ryan Kirby.

He took the trail while I stayed behind on the dirt track. It was a beautiful green morning. The sun had chased off the dawn’s chill, and the air was warm and heavy with pine and goldenrod. The dogs poked their snouts out of the vent holes in the aluminum box and whimpered for attention. When I walked close to pet their noses, their tails thumped hard against the sides of the box so the truck shook on its frame. I got so busy petting and talking to the dogs that I didn’t notice Jack come up behind me a few minutes later.

“We got a bear. A nice one.”

I was suddenly and inexplicably shaken. I don’t know where this feeling came from. It was almost as if I hadn’t expected to hunt bears on this hunt.

“Should I get my gun?” I asked.

“Yeah, unless you’ve figured a better way to do it.”

I hurried to the cab, grabbed my rifle and I shucked four .338s into the magazine. Jack was back getting ready to unload the dogs.

“My rifle’s loaded,” I said. “I didn’t chamber a round though.”

“That’s mighty considerate of you,” Jack said, without taking his eyes off the dogs in the box. He undid the clasp on the door and reached in. The dogs went crazy, shaking and whining.

“Hubie, come on Hubie. No, not you Spot. Hubert!”

Jack pulled a lean hound out by the scruff of his neck. The dog was mostly white with black markings and some gray in the muzzle. Jack held Hubert on the tailgate, and spoke softly as he snapped an orange radio collar around his neck. When the collar was on, Jack released his grip and Hubert dove off the truck and disappeared down the path to the bait.

Jack wiped his forehead and said admiringly, “No one has to tell that dog what to do.”

Three more dogs came out of the box the same way and all followed Hubert’s lead down the trail. When Jack was about to close the door another dog, a half-grown puppy, came halfway out of the box.

“Not you Spot!” Jack smacked the dog very hard on the nose with the back of his hand. Spot tucked his dipstick tail between his legs, then retreated back into the box, whimpering.

“Goddamnit, be quiet!” Jack said. “I can’t hear the dogs on the trail.” He slammed his hand on the box, and the whining subsided.

This stern discipline seemed excessive to me. The discomfort must have shown on my face because when Jack turned around he shook his head.

“This ain’t some poodle park. Out here, a disobedient dog is a dead dog. During my training in July, I lost my best young bitch because she wouldn’t come off a bear when I ordered.”

I nodded, a little chastened by the implication that I was a mere city slicker. We both leaned against the truck and tried to hear the dogs following the bear. Their ooo-oo barks sounded from deep in the woods. Jack was watching the screen of a wireless GPS used to keep track of the dogs.

“They’re on a bear,” he said. “But he’s not going up a tree.”

The dogs in the back of the truck whined and Jack slammed his hand on the box. “Shut-up!”

The barking from the forest grew louder. Jack was still looking at the GPS unit. He leaned over and showed me the screen. The display was four arrows moving across a topographical map. Each arrow was a dog and they were moving in the same direction.

“What’s this line?” I said, pointing to a feature on the display that the arrows were fast approaching.

“That’s the road,” Jack said, jutting his chin behind the truck.

“So the bear’s gonna come across the road?”

“Yup. You better put a round up the pipe. And once you’ve done that, walk about fifty yards down behind the truck on the near edge of the road. When I say the near side, I mean the side he’s coming from. That will hide you better. Try and walk quiet, like you’re sneaking up on a deer. Believe it or not, a bear can get spooked by footsteps even when he’s being run by dogs.”

I tried to keep his instructions straight as I stalked into position. My hands shook as they worked the bolt. I wasn’t entirely confident in my ability to hit a moving bear with a scoped magnum rifle. I looked down at the Meopta 3-9 to see if it was already dialed back to three power. It was, but I twisted the power ring once more on compulsion.

The voices of the hounds came closer and then Jack’s voice called from behind me.

“He’ll be crossing the road any minute. Make sure you don’t shoot a dog by mistake.”

My stomach twisted. The whooping was now so loud that I was sure the bear was about to break across the dirt road any moment. Beside the road directly to my left grew a thick patch of blackberry bushes. The bushes began to shake violently.

I brought the rifle to my eye and my world shrank to a blurry window of green three yards in front of the muzzle. I was too close. I lowered the rifle and took a stumbling step back. Too late. The brush exploded a few feet in front of me.

“Don’t shoot the dog!” Jack yelled behind me.

“I wasn’t going to,” I called back. I didn’t mention that if I hadn’t lowered the rifle and taken a step back, I very well may have pulled the trigger when the first flash of fur passed the crosshairs.

The sounds from the other dogs became more distant. It was clear the bear was not coming out. The hound that had come onto the road walked over and nuzzled my hand, and I gave it a pat on the head, feeling guilty.

Jack walked over behind me. “The bear doubled back.”

“Was it something I did?” I asked.

Jack grabbed some dirt from the road and tossed it in the air.

“Nah, it wasn’t you,” he said. “The wind changed. The bear smelled you and wouldn’t come across the road.”

“I didn’t know the wind mattered on a hound hunt,” I said.

“Now you do,” Jack spat in the dirt and rubbed it out with his boot. “A lot of people come out here thinking this ain’t much of a hunt. They think the dogs do all the work and the bear has practically no chance. It just ain’t true. A bear’s got plenty of chances to escape, especially an educated one. This one’s educated.”

“So what do we do now?” I asked.

Jack checked the GPS display again. “It looks like the bear is taking the dogs across the beaver bog. We ain’t following him through that.”

“So we’re giving up?”

Jack looked incredulous. “ Hell no! No one’s giving up. The road loops around to the other side. If the wind stays this way, we should have a good chance of getting him.”

“What do we do with him?” I said, pointing at the dog.

“Lucy? We’ll put her in the truck. This is her first season. She’s trying hard, but she doesn’t have the experience yet to stay on a bear like this one.”

Jack reached down and scratched behind the dog’s ears. Lucy whooped happily. “Yeah,” Jack said. “She’s done for the day.”

We got back in the truck and rolled along the dusty track with the windows down, listening for the dogs. After a mile or so, we heard them in the distance.

“The bog is on the other side of these trees,” Jack said, pointing to a rather dark and unfriendly looking growth of hemlocks.

We shouldered our way through toward the sound of the dogs’ barking. I say shouldered because there was no freedom of movement in any direction. The only way to move was to make like a fullback muscling his way to the goal line. Everywhere the sharp, brittle branches scraped and jabbed at our clothes and skin. My eyes watered as tiny bits of cracking debris dusted my face.

The whole area was dark as the dusk, and visibility was limited to the yard between my face and left hand, which I was forced to hold out to keep branches from poking my eyes out. Luckily, the worst of it was over after 50 yards or so. The hemlock woods opened up into older growth, where the trees didn’t have so many branches at walking level. But visibility remained poor. It was so hard for me to keep my orientation, I barely noticed the whooping of the dogs growing to a crescendo.

“Get down!” Jack hissed suddenly while pulling me gently down to earth. “Load up kid. The bear’s gonna bust any second.”

I cycled a round into the chamber and pushed off the safety.

“Get your gun up,” Jack whispered. “He’s coming now.”

From the prone position, I welded my cheek into the stock’s comb and looked through the scope.

“There he is!” Jack said.

“Where?”

“Right there . . . moving fast! Don’t you see him?”

“No!” I frantically panned the scope back and forth, but saw nothing but branches, tree trunks and hounds.

“Shoot damnit!” Jack said, his voice close to cracking. “Are you still looking through that scope? Pull your head outta there!”

I looked up and saw it, like black smoke blowing through the trees. I got back into the scope, but it was no use. The bear was gone. The dogs followed, howling and wagging their tails.

Jack exhaled loudly through his nostrils. It was a sound like a buck deer makes when he’s spotted you. Like that, but worse. I wanted to sink into the ground—just disappear. “I’m sorry Jack.”

Jack rolled over on his back and sucked in another deep breath. “That’s alright kid.”

He tucked some Copenhagen under his lip, then offered the tin to me. For a moment I thought about taking some, but decided that was a pretty pathetic way to try and save face.

“I mean what I said,” Jack continued. “You did better than most. I know people who’ve hunted for years who would have lost their heads and ended up shooting a hound or something. The problem is that damn scope. It’s a fancy piece, but it’s not really made for this kind of woods hunting.”

“I’m starting to see that,” I said. I wanted to change the subject. “Hey, have you ever run a bear that was this tough to pin down?”

“One or two a season,” Jack said. “This one’s smart. Been run before I’d guess. He keeps his nose open. They don’t always.”

“Shouldn’t he be tired?”

“Nah. That’s part of the problem. He’s not even running. He’s walking. The hounds are all around him, snapping at his heels. They can’t get him to do the considerate thing and climb a tree so we can kill him. He’s not even the least bit impressed.”

“Can we kill him?”

Jack shaded his eyes with a raised hand and squinted upward. “Probably not today,” he said. “Not in this heat. Then again, we may get lucky. Are you lucky?”

He looked at me, and I didn’t know what to say. Then he laughed and slapped me on the back. It was an awkward gesture that confused me. A lot of things confused me on this hunt.

When we were back in the truck, I noticed Jack was slowing down for potholes and branches in the road. There was less urgency now. We were going through the motions of hunting, the way a wide receiver sleepwalks through his routes in the fourth quarter when the game is out of reach.

I felt myself getting weary all at once, the desire for an afternoon nap suddenly overtaking the desire to kill a bear. The dogs were spent too. Before the truck reached the other side, we came across two of the hounds panting with their long tongues lolling out, lying down in the dirt on the side of the road.

The dogs got up when they saw the truck coming and walked slowly and silently toward the back. One limped noticeably. Jack talked to them low and sweet and poured them water from a cooler on the tailgate. As they lapped noisily, I saw the limping hound had two glistening, six-inch slashes on the ham.

“Is that normal?” I asked.

“I wouldn’t say normal,” said Jack. “But it happens. We’ll disinfect it and rest her tomorrow. She’ll be fine.”

“Are we done?”

Jack’s eyes narrowed. “Do you want to be done?”

I shrugged noncommittally.

Jack chuckled. “We’ve got one more bait site to check” he said. “Depending on how Hubie looks, we can give it a shot.”

Suddenly he reached down for the GPS in his pocket. “Huh.”

“What’s up?”

“It says Hubie’s treed. Probably not the bear, but a bear. Now take a look here,” Jack showed me the GPS screen. There was one stationary arrow a few hundred yards away.

When I stood still and listened, I could hear the steady bark faintly in the distance. Jack slipped the unit back into his pocket and turned to me with an expectant look. So what will it be?

We plowed through more stands of hemlock and into a black swamp.

“Try to step on a rock or one of these mossy tussocks,” Jack warned. “If you slip into that muck, it will eat you up to the waist. I’ve lost three good pairs of Bean boots in garbage like this.”

I slung the rifle over my shoulder and kept on plunging through the skinny birches and cedars that grew on islands across the swamp. As we got closer, I could hear Hubie’s barking clearer. It wasn’t the frantic whooping of earlier, but a steady woof every five to seven seconds.

When we got on dry land, Jack grabbed me by the arm. “Load up. And remember, in the head is dead.” He pulled the Ruger from his hip and checked his load. The cylinder clicked back into the receiver. “Okay, kid, let’s go.”

Kid, I thought. What the hell does he mean? Am I that hopeless?

I tried to push my ego aside as I worked the bolt on the .338 and pulled back the safety. There was a task to be done. At least he’s in the tree, I thought. I hadn’t expected to have to make a head shot. I swallowed the dry click in my throat and pressed on.

I saw Hubie first. He was standing with his front paws against the trunk of a tall pine. When he saw us, his barking ratcheted-up with intensity. He knew what was about to happen. My eyes ran up the tree, and then I saw it. A black ball of fur balanced on a sagging high branch that seemed too small to support its weight.

“He’s not the bear we were chasing before,” Jack called over Hubie’s barks, “But he’s a good bear.”

“He looks plenty big to me,” I said.

“Alright. Then go do it.”

I stepped forward and heard a slightly muted strangling sound, which meant Jack had gotten the leash on Hubie’s neck. My eye settled into the scope. I found the underside of the bear’s head in the middle of the German #4 reticle. The head moved toward the trunk of the tree and I never heard the initial shot. The bear thudded to the ground just as the echo returned to my ears. Hubie went nuts.

I cycled the action and put another round into his ribs. I knew the bear was dead but didn’t want to have Jack shooting just in case. I wanted this bear to be all mine, and I wanted Jack to know I could do it.

The author and Maine guide Jason Mitsin of Bear Ridge Outfitters with a 435-pound black bear killed in September, 2019 with hounds near Millinocket, Maine.

Hubie tugged the leash from Jack’s hands and took a savage hold of the bear’s haunch. When he realized the bear wasn’t going to fight back, he sat down and began licking the blood from the exit wound between the ears. I shook as the adrenaline drained out of my blood, which made unloading the rifle difficult.

Jack sidled over. “That’s a good job.”

“Thanks,” I said.

Jack looked very sternly at me. “I was talking to the dog.”

“Oh.”

Then his face split into a wide yellow-toothed grin. “I’m just spoofing. Great shot, kid. But I did have my doubts. You never know with guys from Connecticut.”

I insisted on gutting the bear myself, and after a few minutes my face ached from smiling. I took a deep nose-full of pine and swamp, dog and gunpowder. “This is a hell of a life you’ve got up here,” I exhaled. “A hell of a life.”

Jack tamped his Copenhagen tin against his thigh. “They keep trying to take it away from us.”

“Yeah, I heard about that,” I said. “A few years ago there was a referendum to ban baiting and hound hunting.”

Jack nodded. “That vote was too close. I think we oughta get rid of the whole referendum process. Mark my words, that’ll be how it ends—the end of hunting, not just here but all over.”

“We don’t allow for the referenda in Connecticut,” I said. “It’s about the only thing we’ve gotten right.”

“Now I’m not against democracy,” Jack said a little defensively. “But you tell me, how is some Starbucks waitress in Portland going to make an informed decision on a bear hunt? She sees a billboard of some little bear looking like it’s frowning and that’s it! She’s voting for the ban!”

“It’s a matter of emotions over reason.”

“And the Facebook and Twitter don’t help. It’s so easy to take a complex issue out of context. Years ago we could talk to the non-hunters, educate them on how bad eliminating the bear hunt will be for the environment. Not anymore. Now the Starbucks waitress sees a sad animal picture on the screen and says to herself, ‘I can’t be seen supporting this.’ So she leaves a nasty comment about hunters, then feels better about herself for a second, then swipes to the next thing.”

“The real problem,” I said, “is you can’t teach people the way of the woods in a thirty-second soundbite. You have to live it.”

A minute passed where nothing was said. We just listened to the whine of the wind and the cracking of branches. Even Hubie was quiet, curled up next to the bear like a puppy nestled by his mother’s teats. Jack reached over and scratched him behind

the ears.

“A couple of more weeks and your bear would have been two hundred pounds, if that means anything to you. It doesn’t mean anything to me. He’ll be good eating . . . that’s what I care about. With all the blueberries this year, the fat will be blue and the meat will be sweet.”

He turned to me with a world-weary smile. “How’s that for

a soundbite?” ν

Author’s Note: The hunt described here is a composite of several hound hunts I have made in Maine. Jack, likewise, is a composite. If any reader is interested in a first-class hound hunt in Maine, I suggest you contact my friend and Registered Maine Guide Jason Mitsin of Bear Ridge Outfitters. Call (207) 329-548 or email:jason@bearridgeguideservice.com.