Angry breakers guarded the Devil’s Elbow of Padre Island’s wild and remote beaches. Watch out, others had warned us, or the surf will eat you alive.

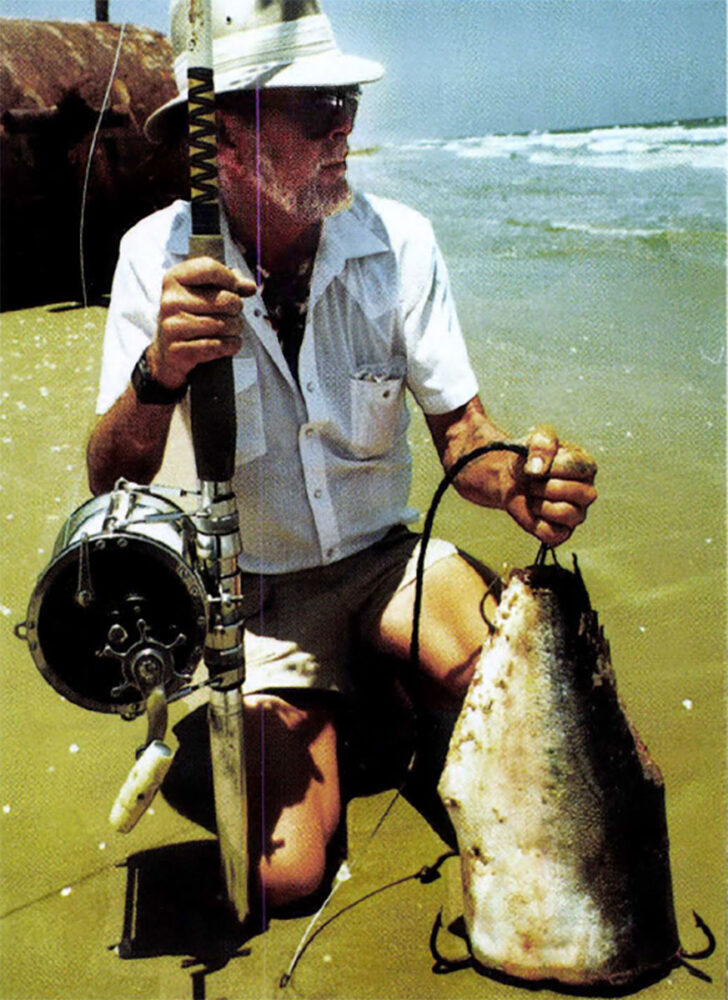

Armed and ready

for tigers, Billy with his 16/0 rig and huge chunk of crevalle laced with massive

hooks.

Billy Sandifer, a three-tour veteran of Vietnam and now a surf-fishing guide, faced the roaring whitecaps and didn’t give a damn.

Out on the first bar where the waves rolled black with clouds of minnows, a whirlwind of screaming pelicans, gulls and terns wheeled and dove from above while gangs of bluefish, mackerel and skipjacks attacked from below. The only relief in sight for the little fish was a calvary of brawny tarpon and jackfish charging the bar to plunder the smaller predators.

The tarpon were the reason Billy had cast caution aside. There’s something about a feeding frenzy that kicks surf anglers into adrenaline overdrive and sensory overload.

As Billy waded into the powerful surf, I followed heedlessly, pummeled by the waves, deafened by the birds’ piercing screams and dazzled by fish that arced like sparks out of the inky waves. Just as we lunged to the top of the bar and came up point-blank with a school of tarpon streaking like lightning bolts through the water, I heard Billy’s faint warning.

He was scuttling backward, pointing, yelling. Over the din of the frenzy I heard “shark!”

Even in a state of hyper-excitement you tend to listen up when your guide is a blunt-talking, roughhewn character with fetishes of tattoos on his hands, shark teeth around his neck and a diamondback’s rattle on his ponytail.

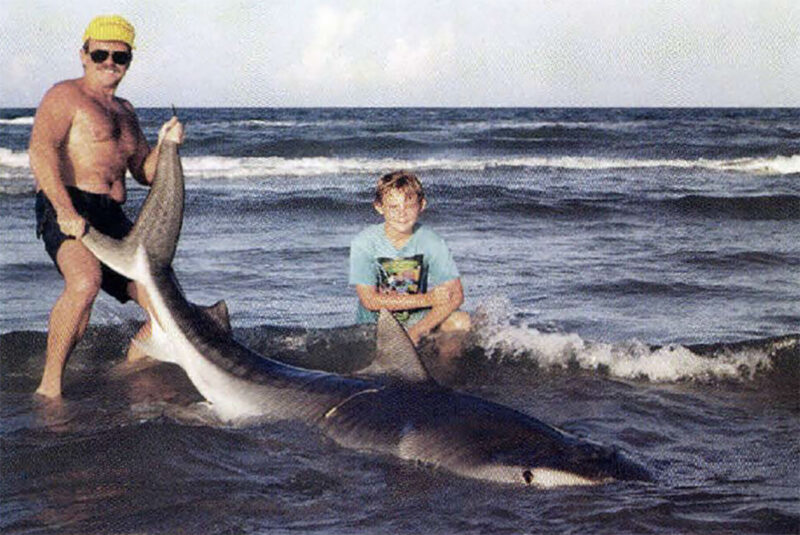

Mike Gibbs with huge Tiger shark.

Suddenly I was backpedaling in record time as a locomotive wearing tiger stripes rumbled down the bar.

“It was a tiger shark. A little one…about ten foot,” Billy said from the safety of the sand. His tone suggested that rump roast of angler could have fit the tiger’s menu just as easily as tarpon.

That thrilling encounter came in the summer of ’94, on my first of many trips to Padre Island with the veteran guide. Back then, Billy was a retired member of a small fraternity known as “big-rig fishermen” — men who wielded massive 14/0 and 16/0 reels to fight the largest sharks, one on one. Easily triple the size of tackle that bluewater anglers use for marlin and tuna, the big rigs are capable of fishing baits up to50 pounds at distances of a quarter-mile from shore, and with enough backing to stop the runs of a thousand-pound shark.

The magnificent obsession of these dedicated fishermen was the tiger shark, known to reach 18 feet in length and with a girth of eight feet or more. The International Game Fish Association lists the all-tackle record at 1,780 pounds. The official Texas record is 1,170pounds, but tigers estimated at more than1,400 have been caught along the Texas coast. Between their sleek, striped bodies and their unusually wide, cavernous jaws, tigers are at once beautiful and fearsome, a combination of size, strength and ferocious fighting spirit that ranks them with the great white and mako as the most coveted of the gamefish sharks.

But the one characteristic that sets them apart is their penchant for prowling warm, shallow shorelines, where they are just as likely to feed on sea turtles and tires as porpoises and people The tiger ranks only behind the great white in recorded fatal attacks on humans.

There never has been many big-rig anglers, even during the heyday of shark fishing in the 1970s. A few old-timers like Karl Boardman, Norman Bateman and the Loveday brothers became local legends for catching 11- to 13-foot tigers weighing from 800 to 1,400 pounds. These men were later joined by other local tiger hunters such as Sandifer, Mike Gibbs, David Green and Charlie Krause. Today, there are no more than two dozen fishermen who still own big rigs and have the knowledge and the will to use them.

Texas shark fishermen still talk about August of ’92, when eight huge tigers were caught in a single week, a feat that has never been equaled. Mike Gibbs caught four of them, including an 11-footer and a 12-footer on the same day, another record.

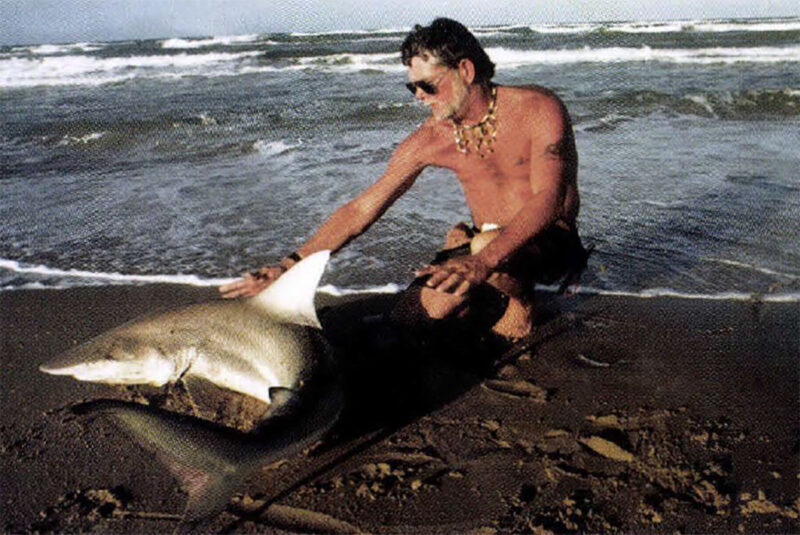

Unidentified Texas angler with giant catch.

The most recent breakout of tiger fever struck Padre Island beaches in July of 1996. It started at Devil’s Elbow, where three tigers in the eight- to ten-foot range were caught by anglers who were bottom-fishing for lesser species of shark. These catches of relatively small tigers were followed by a half-dozen sightings and hookups with much larger brutes.

“I heard about those tigers and felt that squirrelly feeling start climbing up my spine,” said David Green of Corpus Christi, who had hung up his big rig to become a successful Laguna Madre fishing guide after catching a 12-foot 4-inch tiger in 1992.

In Billy Sandifer’s case, the contagion was more direct. After helping a client catch a 350-pound bull shark on a 6/0 rig, Billy had something pick up his bait in the Padre Island surf and strip off 500 yards of 80-pound test line against a drag tightened almost to the stops. The fish’s run was too strong for a bull shark and too fast fora hammerhead. Rather, it had the earmarks of a tiger in the 12-foot range.

“I’ve seen the tracks of a tiger in the Big Shell,” Billy said during his phone call to me the next morning, “and I got the fever again for the first time in ten years.” That meant re-activating the big-rigs the 50-year-old guide had put away after counting coup on several 12-foot-plus tigers in the 1980s. It also resulted in my chance to join him for a firsthand look at one of the most unusual and exciting brands of fishing anywhere.

In August of that summer, we rolled out in Billy’s rusty Suburban, a kayak strapped to the roof and imposing 16/0 rigs locked in the rod rack, following a route that had become familiar to both of us. This run, like all the others, put the mainland in the rearview mirror and crossed the Laguna Madre via the JFK Causeway to reach the north end of Padre Island, the nation’s longest barrier island at more than 120 miles in length.

It looks pretty civilized at first glance, with the first five miles of Park Road 22 taking you past hotels, condos, waterfront subdivisions and other hallmarks of the resort industry But the development soon recedes to an unbroken expanse of marsh and prairie stretching for another five miles to the entrance of Padre Island National Seashore, which encompasses nearly 80 miles of the island’s length.

Billy and a small blacktip pulled from the Texas surf.

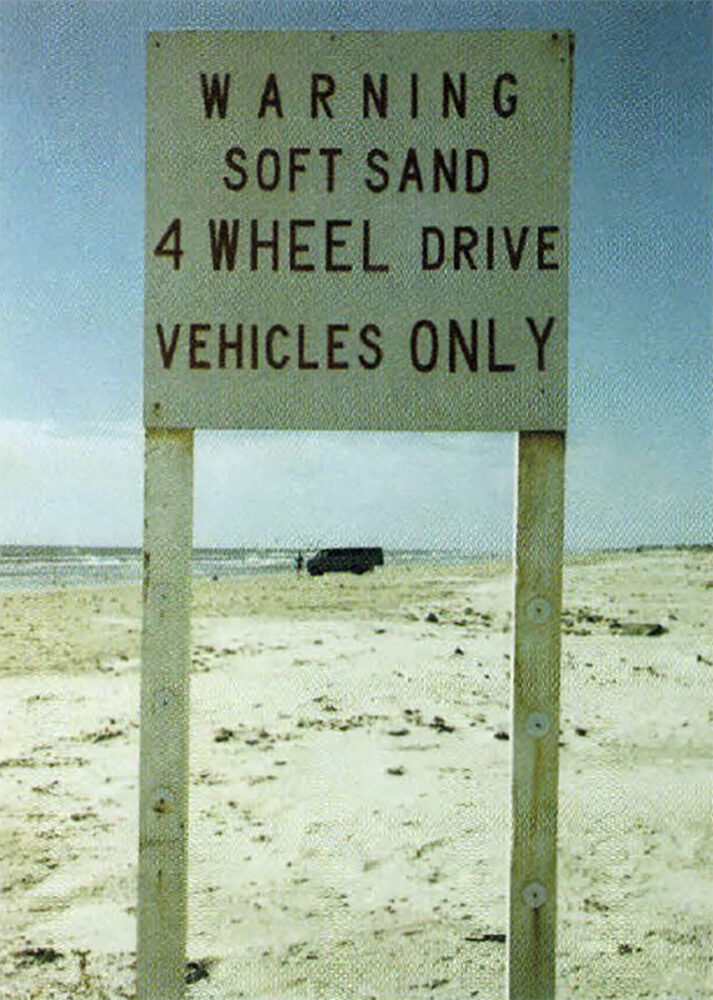

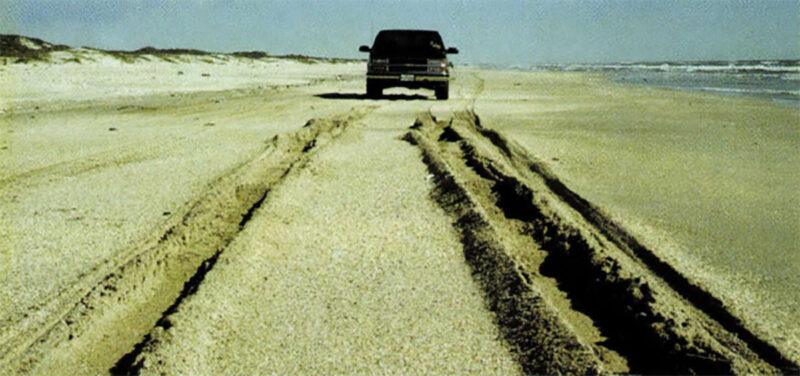

Six miles beyond the visitor’s center, the pavement ends at the groomed sands and tame surf of Malachite Beach where the tourists gather. Four more miles down the beach, however, stands the infamous “Four Wheel Drive” sign that spells out warnings to those who would venture farther. From here, it’s 60 miles of nothing but surf, beach, dunes and sand-flats — the longest stretch of undeveloped beach accessible to four-wheeling surf anglers. No water, no gas, no emergency help standing by.

It also marks the gateway to Billy’s fishing grounds.

Chugging along at 15 mph gave me ample opportunity to learn more about Padre Island and Billy’s star-crossed career.

Born on the coastal prairies of Texas, Billy grew up around cattle and crops, living for getaways to fish the surf. Most of that came on weekends during the school year and weeks at a time during the summer.

After years of fighting and hell-raising on and off the battlefields of Vietnam, Billy retreated to the island’s remote beaches to live as a hermit for eighteen months while he “got his head straight.” The cure wasn’t completely successful, because more hell-raising followed, along with several wives and a job history that ran the gamut from border patrol agent to shrimp boat deckhand.

When he finally became clean and sober, he gravitated back to the place that had always seemed to suit him best — a rough and untamed beach where he vowed to make a professional stand as a fishing guide.

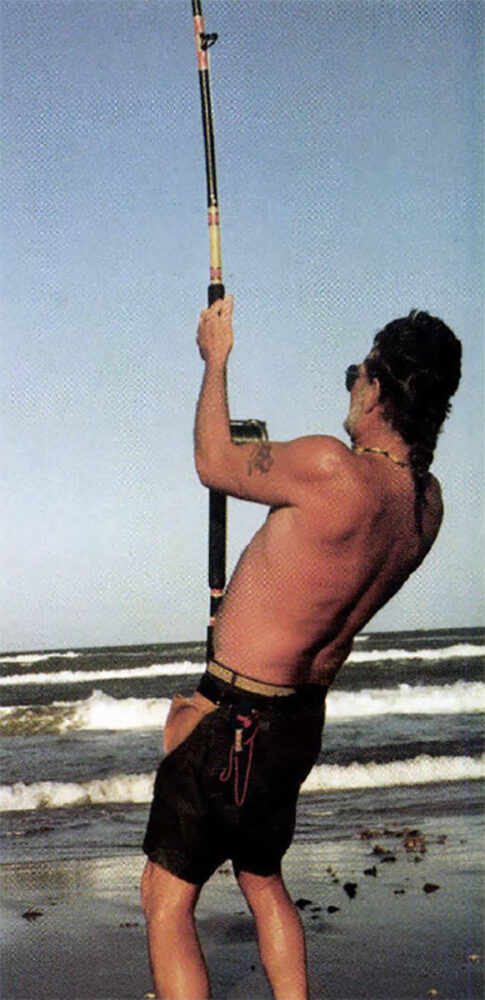

Billy uses his kayak to carry the huge chunk of bait well out from shore.

Billy’s uneven earlier life deserves mention only because most big-rig shark anglers, dead and alive, seemed to have been rebels of some sort. Today, Billy is recognized as a self-taught naturalist of island ecology and an expert regarding its flora and fauna. He has even received conservation awards for his efforts to preserve the island.

As a student of the island’s history, Billy talked of its earliest residents, the fierce and cannibalistic Karankawa Indians, a mysterious tribe of exceedingly tall people who covered their bodies with tattoos and pierced their faces with skewers of cane. He related old tales of fights and feasts, shipwrecks and lost treasure, ghosts and haunted cold spots on the sand.

I believed every word of it.

To Billy Sandifer, the island is a living thing, which is not far from the truth. From its inception, Padre Island has been a creature of currents, starting with the great Loop Current of the Gulf Stream that rolls along the entire Gulf Coast from the Yucatan to Florida. This is the current the Spanish galleon rode to riches or ruin, depending on the mood of the storm-prone gulf. But the real work of island-building was done by “gyre currents” that spin off the Gulf Stream to sweep along the beaches of Mexico and Texas from opposing directions.

These currents picked up alluvial sand washed from coastal rivers and carried it along the shore to build sandbars that gradually emerged from the sea to become barrier islands. At Padre Island, they collide head-on and contend in a titanic, ancient and continuing shoving match. This millennial struggle shifts back and forth along miles of beach, stirring up immense amounts of sand and shell to be pushed ashore. The results are most evident in the 60 miles of beach beyond the four-wheel drive sign.

On one side is a ridge of dunes rising as high as 50 feet above sea level. Between the dunes and the water’s edge is unforgiving beach front, with names like Big Shell and The Codo. Of the two, Big Shell deserves special mention. This 12-mile stretch of seashells and deep, soft sand has swallowed entire vehicles. A beach-comber bending over to admire a prized shell can be standing on the roof of a pickup and never know it.

But surf anglers brave these obstacles for what lies on the watery side of the sand, where the contesting currents create troughs and holes eight feet deep. The surf at rare times can be as emerald green and placid as a swimming pool, but more often it serves up immense breakers, powerful undertows and sudden drop-offs. Here, tiger sharks and other big predators don’t just cruise the edges, they sometimes beach themselves in frenzied pursuit of their prey.

But surf anglers brave these obstacles for what lies on the watery side of the sand, where the contesting currents create troughs and holes eight feet deep. The surf at rare times can be as emerald green and placid as a swimming pool, but more often it serves up immense breakers, powerful undertows and sudden drop-offs. Here, tiger sharks and other big predators don’t just cruise the edges, they sometimes beach themselves in frenzied pursuit of their prey.

Depending on the season and the surf, Billy sometimes goes forth as a “plugger,” using light tackle to cast lures for speckled trout, redfish and Spanish mackerel as long as your arm. Just as often he is a “Iong rodder,”using 4/0 and 6/0 reels to fish for jack crevalle, king mackerel, tarpon and smaller sharks.

More than one plugger standing in the edge of the surf and casting into a feeding frenzy has been shocked to see a whole gang of big sharks cross the bar to join the fray at rod-tip range. These swift predators include acrobatic blacktips, bull sharks up to 350 pounds and hammerheads and lemon sharks weighing 500 pounds or more. But the greatest shark drawn to the deep surf of Padre Island is the tiger.

After arriving at the west end of Big Shell some 29miles from the end of the pavement, Billy began preparing the 16/0 rig. From a cooler he pulled out an 18-pound chunk of jack crevalle embedded with three 16/0 hooks attached to short leaders of braided steel. Nails had been driven through the eye of each hook to hold them in place, and the short leaders were shackled together where they emerged from the jackfish.

Hanging below the bait were four heavy sinkers rigged in tandem to provide 20 pounds of secure anchor in the strong current. Billy proceeded to attach the bait and weights to 20 feet of 1,500-pound steel leader tied to the end of the rig’s heavy line. “I’ve seen tigers bite through this kind of leader like it was thread,” Billy said.

He then loaded the bait and terminal rigging into his kayak and began the tricky if not dangerous task of paddling through the breakers, while pulling line off the reel which he had set in free-spool. If the surf hadn’t been relatively calm, our tiger hunt would never have gotten off the beach.

About 300 yards from shore, Billy dumped the bait just beyond the second bar, a favorite gut for prowling tigers. Then he returned to the beach where he placed the rod in an 18-foot-tall pipe rack to keep as much line as possible from becoming weighted down with seaweed. Finally, Billy stood back and eyed his efforts with noticeable pride “There aren’t many anglers left who know how to rig and set a bait for big sharks,” he said.

“Most big-rig fishermen never hook more than two or three tigers in a lifetime,” Billy went on, “if they hook any at all. Success comes through the accumulation of years. You get old and gray and lose your teeth, and suddenly, there she is.

“Most big-rig fishermen never hook more than two or three tigers in a lifetime,” Billy went on, “if they hook any at all. Success comes through the accumulation of years. You get old and gray and lose your teeth, and suddenly, there she is.

“Our waiting began in earnest at sundown when a tiger-colored moon three days past full began its climb from the gulf. With the measured beat of the breakers providing background music, Billy built up the bonfire of driftwood, then disappeared into the shadows for what seemed like an hour.

When he returned, he stood in a whirlwind of sparks above the fire, his face glowing and eerie with the freshly painted designs of a Karankawa on the warpath. Whoa! I wouldn’t have been surprised if he had broken into a dance and chant to call upon the Great Spirit to deliver up a tiger.

Squatting by the fire, Billy struggled to explain the deep feelings that drive big-rig fishermen. He spoke of ancient hunters who pursue mammoths with spears and of men who measured themselves against the great predators. “Hunting tigers is the essence of who we are, and we lose something of ourselves when we hang up our big rigs,” Billy lamented.

Yet many big-rig anglers retired on the heels of their greatest triumph, shortly after “winning their jaws” Like Mike Gibbs. During that week he caught four tigers, he managed to tag and release all but one, a female weighing close to a thousand pounds Gibbs, who now captains an offshore sport-fisher, told Billy that “something went out of me when that fish came back to the beach.”

Although he had come to hunt tigers, Billy had no desire to kill another one. In that sense he was a man at war with himself, because he realized there was always the chance of inadvertently killing any fish that he hooked.

Billy explained that our best chance would come after midnight, a prediction that had some science on its side. Years ago, biologists with Texas Parks and Wildlife conducted a survey of surf fishes. They anchored a heavy trotline in the surf, baiting it in the morning and running it in the evening. They regularly caught five- to six-foot sharks.

Once, when they switched to baiting the line at night, the next morning they found only the heads of several midsized sharks, what remained after the big guys finished cannibalizing the carcasses. News of the survey ended my nighttime wading in the surf.

As midnight drew nigh, Billy prepared me for what to expect if a tiger picked up the bait. The battle might last as little as two hours or continue well past dawn, depending on the size of the shark, the strength of the current, the weight of seaweed on the line and where the fish was hooked. He recalled one battle with a foul-hooked tiger that lasted over 10 hours before the fish pulled free, leaving Billy’s body imprinted with blood-blisters from the pressure of his fighting harness.

Regardless of how long the battle lasted, it would be won when Billy waded into the surf to lasso the shark’s tail and dragged it into the shallows to remove the hooks. If the shark was too spent to fend for itself, Billy would walk it through the shallows until it revived enough to swim off on its own.

As the breakers reared, curled and broke under the silvery moonlight, their white, serrated edges created an illusion of teeth and jaws. It was the only shark image that came and went that night, yet it was conducive to a certain reverie regarding the place and players: A wild and treacherous surf, a dangerous predator and a crazy breed of angler daring enough to tackle both.

Poetic justice argued for the intervention of fate to bring all three together, but fate declined. The big 16/0 rig remained mute and unbowed as the rising sun cast flickers of light that glittered and finally fizzled, along with our chances.

Instead of poetic justice, what came to me in the fiery sunrise were the words of William Blake. In his poem “The Tiger,” Blake came close to capturing man’s, fascination with the tigers of land, sea and soul. Speaking of figurative tigers burning bright in the forests of the night, Blake asked, “What hand dare seize the fire? Try a strange breed known as the big-rig shark fisherman.

Zane Grey, America’s master storyteller of the old West, was a passionate angler. He fished as many as 300 days of the year! This collection, first published in 1925, describes his fishing adventures in exotic locales throughout the Pacific region. Illustrated with more than 100 photographs from the author’s private collection. These stories capture the drama and excitement that Grey experienced in being the first person to fish many waters―from the Galapagos Islands to Cabo San Lucas―and in being the first to catch and document many new species of fish. No lover of Zane Grey storytelling will want to miss these real life adventures.

Zane Grey, America’s master storyteller of the old West, was a passionate angler. He fished as many as 300 days of the year! This collection, first published in 1925, describes his fishing adventures in exotic locales throughout the Pacific region. Illustrated with more than 100 photographs from the author’s private collection. These stories capture the drama and excitement that Grey experienced in being the first person to fish many waters―from the Galapagos Islands to Cabo San Lucas―and in being the first to catch and document many new species of fish. No lover of Zane Grey storytelling will want to miss these real life adventures.

Zane Grey was born in Zanesville, Ohio, in 1872. He was one of America’s most prolific and beloved authors, writing almost ninety books. He died in 1939 in Altadena, California. Buy Now