“And the boy…was he there, Bill?”

I hauled off and went squirrel hunting the other day. Not so remarkable, I suppose. Except that the whitetail rut was in full blaze, and bird season was in and it’s been a hell of a long time since I’ve forsaken a prime-time deer stand or a pointing dog for a bushy-tail. But the mood grabbed me and wouldn’t be denied, I suppose for the same reason I’ve done a lot of other unusual things the last year. Besides, I had this little Remy. 22 lever-action rifle I acquired as a part of the same yearning. That needed going too. Cause it looks something like the octagon-barreled Marlin I had back when, with the bum extractor, that always left me a shot short when it could have counted. And a lot like the old Golden Boy .44 I wanted for when I wasn’t off huntin’, and took up cowboying and rode a stick horse scoutin’ for Injuns.

I hauled off and went squirrel hunting the other day. Not so remarkable, I suppose. Except that the whitetail rut was in full blaze, and bird season was in and it’s been a hell of a long time since I’ve forsaken a prime-time deer stand or a pointing dog for a bushy-tail. But the mood grabbed me and wouldn’t be denied, I suppose for the same reason I’ve done a lot of other unusual things the last year. Besides, I had this little Remy. 22 lever-action rifle I acquired as a part of the same yearning. That needed going too. Cause it looks something like the octagon-barreled Marlin I had back when, with the bum extractor, that always left me a shot short when it could have counted. And a lot like the old Golden Boy .44 I wanted for when I wasn’t off huntin’, and took up cowboying and rode a stick horse scoutin’ for Injuns.

Could be the same notion, I ’spect, that led me to strap on a Colt a week later, and stuff the belt loops full of fat silver cartridges. Wore it around all day, even though there weren’t no rustlers or yahoos near bouts that needed killing. (Or rather there were, but I couldn’t do it with the impunity I could when I was 10 years old.) It was just ’cause it felt good on my hip, and it went with my worn-in Filson tin chaps, and when I climbed on the gelding to road some dogs, I could kinda’ imagine, under the Stetson . . . well, it could be Wyoming or New Mexico, or Montana Territory. And I put on a clean shirt and knotted up a bandana about my neck case I was to ride south to Laredo and run into the school-marm.

“Gat-up, horse.”

Got a birthday card after six decades. On the front there’s a young cowpoke straddlin’ a corral fence at twilight, a-gazin’ wistfully up at a crescent moon all lazy on its back. “I’m believin’ there’s a lot of the six left in the sixty,” the old friend who sent it wrote inside. She’s got me pegged about right.

I ain’t the only one ridin’ for the brand. I can tell you easily why cowboy action is among the fastest growing segments in shooting sports, and why two-thirds of the punchers doin’ it have got hoarfrost and woodsmoke in their whiskers. It ain’t really about cowboys.

It’s the same reason, just afterwards, I pulled out the little .22 Remington Sportsmaster I learned to shoot on, and killed a tin can. Whipped out my jack-knife and played a round of mumbly-peg on the cabin porch. Whittled free the stick-bow hiding in a hickory billet. Just before I cut down a dogwood fork and whacked up an inner-tube. Actually it took three. They don’t stretch like they used to, you see. All to build a beanshooter and shoot a jaybird in the ass. To see maybe I remembered how.

When Daisy dispatched the Millennium Edition Red Ryder BB gun in 2000, I bought the first one in town, to honor the original hanging on my wall. Then two more, ’cause I plan never to be without one, and like anything else anybody really wants, they’ll up and quit making ’em one day agin. Took one out, kicked around a wheat field and shot a grasshopper on the rise. Hell of a bunch of fun.

October come last I found a black gum stump, holler inside and put together a rabbit box. You got to carve out the trigger stick and the little notches on the dead man just right — remember? — to get it to go off jus’ so. I waited for the first cold snap like it was Christmas, and when it came, I set my gum out by a honeysuckle thicket. I wanted for a laid out roastin’ ear patch, by a broomstraw field, with snow laid up in the rows and the dry brown stalks all rattly in an icy December wind. But there ain’t many left any more, shame be. So I had to set it longside a three-year cut-over, which ain’t nearly as picturesque. I forgot to put an apple slice inside, but when I did, I caught one first whack. After that I grew homesick for the beagles I once had, and went out and looked around for the man what had a bunch. Twelve inchers. Asked him would he take me huntin’. We went around stompin’ brush piles.

“Hike in here, Jack Root him out, Dot.”Arroooaahh! Arooooo-agh! One of ’em opened up and then the God’s dozen of ’em jumped in, and Mister, they helped him to a ride. Whooooeeegh! I couldn’t help myself. I heaved light in and bawled along with ’em. My Heavens, that’s music. We get ourselves off in Mozambique, and Mongolia and Madagascar even, and it’s nice and all —and I’ll go back, don’t get me wrong — but we forget things like that.

And ever once in a while, we have to go lookin’ all over again. To prove to ourselves he’s still there. Along about sixty, it looms imperative.

Take Bill Crews, who’s seventy-something. Ran into him at the feedstore one sweltry, day last July. He’d aged a lot, his hair gone white, and he stood humped to the shoulders, like he was bent permanently over a Number Eighteen Lightning Bug, tryin’ to thread the hook. I don’t know what brought it around — what he told me — some nip I’d told him about. But it seemed less than coincidence.

“Two year ago, Mal Carter and me loaded up and drove six hun’erd miles,” he said.

“To a trickle of a branch runs behind my Grandpappy’s house in Mississippi. Last time we’s there, we’s best buddies and bare-foot.”

He laughed.

“Course Grandpap, he ain’t there no more,” he said soberly. “Ain’t been for fifty years. Didn’t last more’n a year past Gran’ma. The house neither. The man bought the farm, tore it down and the bam to boot, and put som’thin’ ugly up in its place bigger than the house an’ the barn together.

“Course that old man’s gone now hisself,” Bill added with a thin grin. “But we ast his boy could we go down to the branch, and he allowed ‘yes.’ So we did.”

“Course that old man’s gone now hisself,” Bill added with a thin grin. “But we ast his boy could we go down to the branch, and he allowed ‘yes.’ So we did.”

“What was there, Bill?” I said.

“Well, nothin much, like al’ays,” he said.

“But on the way we stepped to the woods and cut two poles, tied on a hank of line and pegged on a corkstopper. Used the better part of a morning finding the damn things. You got any idea how painful it is findin’ a plain old cork-stopper these days?” I shook my head “No.”

“Course Rufus Callaway’s apothecary ain’t there in town no more,” he said, “and that’s where we al’ays got ’em. He’d give’em to us for free . . . and a pierch or two.

“Granny’s chicken lot ain’t there no more neither, much less the chickens, so we couldn’t dig worms worth a damn. We’d as well go buy ’em at the store, I finally told Mal. The biggest one weren’t the length of your whizzle.

“But we got to the little black pool below the old rock dam, and it was still there. ‘Cept I could spit across it now where I used to have to swim. And somebody’s goddam six-pack plastic was floatin’ from a limb the other side.”

I frowned and spit on a tire.

“We got to do this like we used to, Mal,” Bill told me he said to his old friend, “and we dug out two straight pins, and bent ’em up like we remembered and tried to catch a redbreast. We did, partly, but they kept fallin’ off,” and Mal said “he couldn’t never catch no fish on a straight pin no-how.” So he dug out this little wooden tube he’d kept all the years, that had a green-paper Pfleuger label on top, opened it and pulled out a couple of long-shank Aberdeens. Handed me one. “And we kinda napped along with the sun shinin’ in and the heat off the rocks we’s sittin’ on warmin’ our backsides. Catchin’ a four ounce sunfish here and agin.

“Bout sundown we took a drink, got in the truck, and drove six hun’red miles back.”

“And the boy . . . was he there, Bill?” I asked quietly. I could see we’d been on the same pilgrimage.

And he looked at me for a second or two like he was off somewhere and not sure what I was talking about. Then he broke honest and grinned.

And he looked at me for a second or two like he was off somewhere and not sure what I was talking about. Then he broke honest and grinned.

“You’d not know it jus’ lookin’,” he said.

“But he’uz still there.”

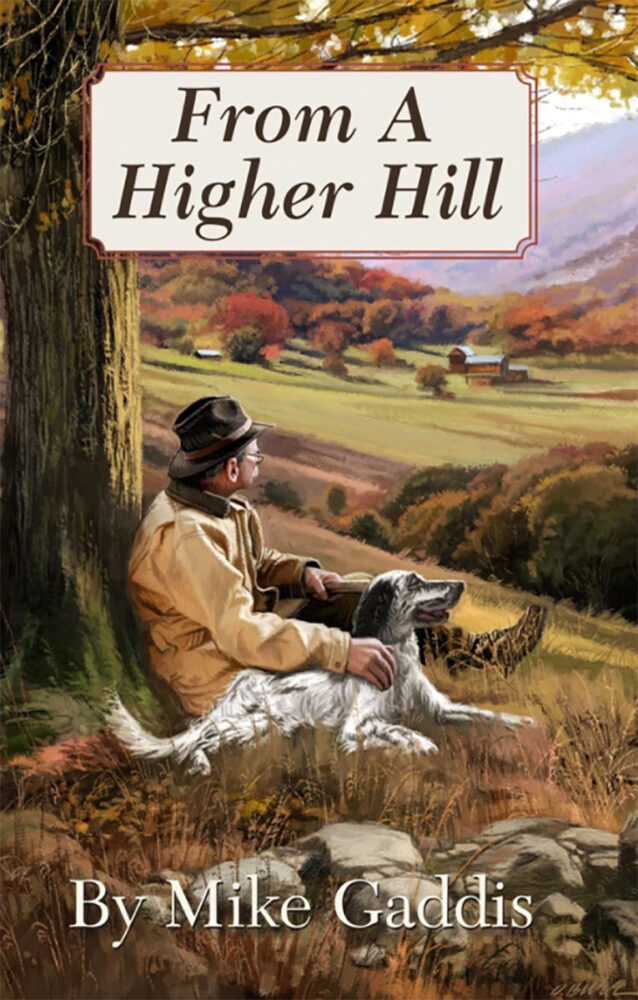

Life can be likened to ascending a mountain. The higher you climb, the more years you have beneath you, the farther you can see, the more unobstructed the view, the more you understand.

Life can be likened to ascending a mountain. The higher you climb, the more years you have beneath you, the farther you can see, the more unobstructed the view, the more you understand.

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now