Roosevelt had said, “I want Uncle Sam to have a better African collection than anybody else”; he accomplished his purpose.

Well-known African explorer-hunter Carl Akeley, a contemporary of Theodore Roosevelt, had a simple answer about why Roosevelt’s African expedition was so enormously more successful than expeditions of other hunters. “Few men,” said Akeley, “could get so much out of a trip to Africa as Roosevelt could because few men could take so much to it.” Indeed, the ex-president took with him a lifetime’s experience as a hunter and practicing naturalist; he took an immense knowledge of Africa and its wildlife acquired from intensive book-study and from the personal counseling of hunters noted for their African safaris; he took the greatest amount of the best equipment ever assembled for such a venture; he took men superbly qualified to manage various phases of the expedition; and he took his own indomitable spirit, very alert mind, and tremendous curiosity.

Long before Theodore Roosevelt’s second term as president ended in March 1909, he decided to take a hunting trip through Africa as soon as he was free to do so. Over a year before he left the presidency, he wrote a friend: “I am already looking away from politics and toward Africa . . . I do not want to take the African trip as a mere holiday . . . I shall go on a regular scientific trip, with professional field taxidermists to cure the trophies and arrange for their transport back to this country.” About the same time, he wrote a famous British big-game hunter, John Henry Patterson, for advice about the trip: “I shall be 50 years old . . . But I am fairly healthy, and willing to work in order to get into good game country . . . Now, is it imposing too much on your good nature to tell me where I ought to go to get really good shooting?” Patterson complied.

On every possible occasion during 1908, Roosevelt invited to the White House men who had hunted or traveled on the “Dark Continent,” and in so doing acquired information and advice from the leading African explorers of the era. By June 1908, he had worked out an itinerary that would cover about a year. He asked 18-year-old Kermit, his second son, if he’d like to take a leave of absence from Harvard the next year to make the trip. Kermit was delighted at the prospect. (Each of Roosevelt’s four sons was introduced to hunting and wilderness life by their father, and each developed into a skillful hunter.)

Roosevelt’s safari on the move – part of the entourage of more than 275 porters, gun bearers, tent boys, askaris and saises.

The president engaged in intensive correspondence related to the acquisition of proper equipment and clothing, including “leather stockings, spine pads, wool socks, sun helmets, mosquito nets, hunting knives, waterproof matchboxes, compasses, portable bathtubs.” Roosevelt’s main outfits included heavy hobnailed shoes, tan army shirts, and khaki trousers with leather-faced knees. One important decision was how many spectacles to carry. Through the years he had been having increasing trouble with his eyes, and from early 1908 on was almost blind in his left eye — a condition he did everything possible to keep secret until after the safari. He took nine pairs of glasses on the African trip.

Another decision was how much liquor to take. “I do not believe in drinking while on a trip of this kind,” he wrote one of the men helping him with preparations. “I wish to take only the minimum amount of whisky and champagne which would be necessary in the event of sickness.” During 11 months on safari he drank only six ounces of alcohol.

Both Roosevelt and Kermit gave grave consideration to selecting firearms for the safari. The father wrote his son: “I think I shall get a double-barreled 450 cordite, but shall expect to use almost all the time with my Springfield and my 45-70 Winchester. I shall want you to have a first-class rifle, perhaps one of the powerful new model 40 or 45Winchesters. It would be a good thing to have a 12-boreshotgun that could be used with solid ball. You should also have a spare rifle. . . We would thus have four rifles and the shotgun between us … It is no child’s play going after lion, elephant, rhino and buffalo. We must be very cautious; and we must always be ready to back one another up. . ..”

Roosevelt wrote later: “My rifles were an army Springfield,30-calibre, stocked and sighted to suit myself; a Winchester405; and a double-barreled 500-450 Holland, a beautiful weapon presented to me by some English friends. Kermit’s battery was of the same type, except that instead of a Springfield he had another Winchester shooting the army ammunition, and his double-barrel was a Rigby. In addition, I had a Fox No. 12 shotgun; no better gun was ever made.”

Roosevelt never went anywhere without taking selected books with him. Months before the African trip, he made a list of about 60 titles, varying from the Bible to Poe and Mark Twain, which he wished to take “into the jungles of Africa.” His sister, Corinne Robinson, had copies of all trimmed down, bound in pigskin, and packed in a specially constructed aluminum-and-oil cloth case. Roosevelt’s “Pigskin Library” was a topic of much discussion in the American press — as was everything that leaked out about the president’s forthcoming expedition. One newspaper editorial went to far as to tastelessly suggest that, considering the exciting life Roosevelt had already enjoyed, it would be appropriate for him to “meet his Maker” in some sensational manner in the wilds of Africa. The president thought that very amusing; his wife Edith did not.

In June 1908, Roosevelt conceived the idea of seeking sponsorship by the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum and wrote to Charles D. Walcott, secretary of the Smithsonian: “Now it seems to me that this opens up the best chance for the National Museum to get a fine collection, not only of the big-game beasts, but of the smaller animals and birds of Africa. . . I shall make arrangements in connection with publishing a book which will enable me to pay for the expenses of myself and my son. But I would like to get one or two professional field taxidermists, field naturalists, to go with us, who should prepare and send back the specimens we collect. . ..”

Walcott, knowing well how very poor the Museum’s African zoological and botanical collections were, enthusiastically agreed. The Smithsonian selected Dr. Edgar Mearns, a US. Army naturalist, to accompany Roosevelt and agreed that Edmund Heller, a 26-year-old University of California professor chosen by Roosevelt, and naturalist Alden Loring of Owego, New York, would be Mearns’ assistants. All were capable taxidermists. Arrangements were made so that funds for the three-man Smithsonian contingent would be supplied by private donations, with Andrew Carnegie the largest contributor. Roosevelt made an agreement with the scientists that no other member of the expedition was to do any writing whatsoever about it until his own accounts had been published.

He had no difficulty covering the expenses for himself and his son. Scribner’s offered him $25,000 for a series of magazine articles to be sent from Africa, with the understanding that they would later be published as a book. Before the president had time to accept, Collier’s offered$50,000 and McClure’s $60,000. He preferred Scribner’s, which had published much of his earlier work; he asked Scribner’s to up its bid to $50,000 and, when Scribner’s agreed, signed a contract with that publisher, even though Collier’s had raised its offer to $100,000.

Roosevelt became furious in late 1908 when he learned that certain reporters were trying to make arrangements to accompany him and send back dispatches. He fired off a letter to the Associated Press: It would be, he stated, “an indefensible wrong, a gross impropriety,” to attempt any interference with his privacy; it would be “a wanton outrage” for any publication to make reports on his travels through Africa because such would adversely affect his “individual pleasure and profit.” He issued a public statement pointing out that, at the time of the safari, he would be an ex-president, not a president, and that as such he demanded privacy. He assured the public that any statements attributed to him during his absence would be false. Roosevelt told his military aide, Archie Butt, that, if a certain newspaper man caught up with him in Africa for even a minute, his report of expenses to the National Museum would include: “Five hundred dollars for furnishing wine to cannibal chiefs with which to wash down a reporter of the New York Evening Post.”

Months later, while he was inland in Africa, he became friendly with two wire service reporters who assisted him with mail and in editing his articles, and he allowed them to follow the expedition.

Many of Roosevelt’s friends pleaded with him not to make the trip, with most basing their arguments on the much-publicized danger of deadly African sleeping sickness. Colonel Cecil Lyon, who had hunted with Roosevelt in the West, voiced a different opinion, however: “They don’t know the Colonel. He may be in danger of wildebeests, rhinoceri, dik-diks, lions or snakes, but no one who ever saw him hunting would believe that sleeping sickness could ever catch up with him. That man’s immune from that disease.”

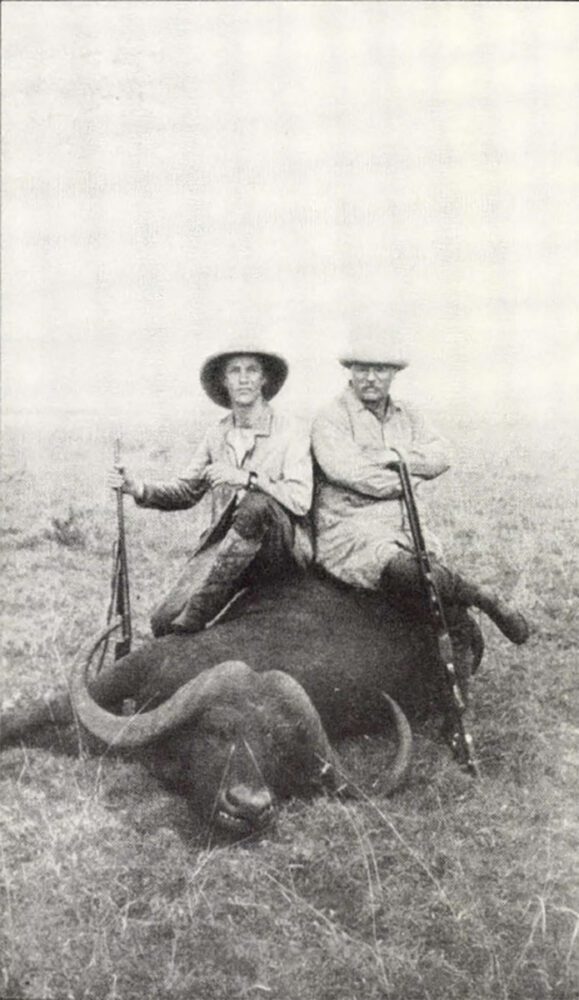

Roosevelt and Kermit with horns from a giant eland taken as a specimen far the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum.

Roosevelt and Kermit had passage booked for Italy on the Hamburg, to leave from Hoboken, New Jersey, on March 23,1909. By sailing date, Roosevelt had been an ex-president less than three weeks; he was now, at his choosing, “Colonel Roosevelt,” most often called simply, “The Colonel.” He spent most of March 22 supervising the delivery and loading of the expedition’s baggage-about 200 cases, each six-by-four feet, and each stamped, “Theodore Roosevelt, Mombasa, British East Africa.”

At Roosevelt’s direction, each of the food boxes contained, in addition to provisions endorsed by experienced African hunters, cans of Boston baked beans, California peaches, and tomatoes. An idea of the naturalists’ equipment and supplies may be acquired from the fact that they included four tons of fine salt for curing skins.

The Colonel received many parting gifts, but none pleased him more than the last three: a small gold ruler with a concealed pencil in one end from the new president, inscribed, “Theodore Roosevelt from William Howard Taft — Good-bye, Good Luck and a Safe Return,” delivered along with a personal letter from Taft by Archie Butt; a plaster cast of an elephant’s head, marked for proper shooting, from Carl Akeley; and a rabbit’s foot from John L. Sullivan.

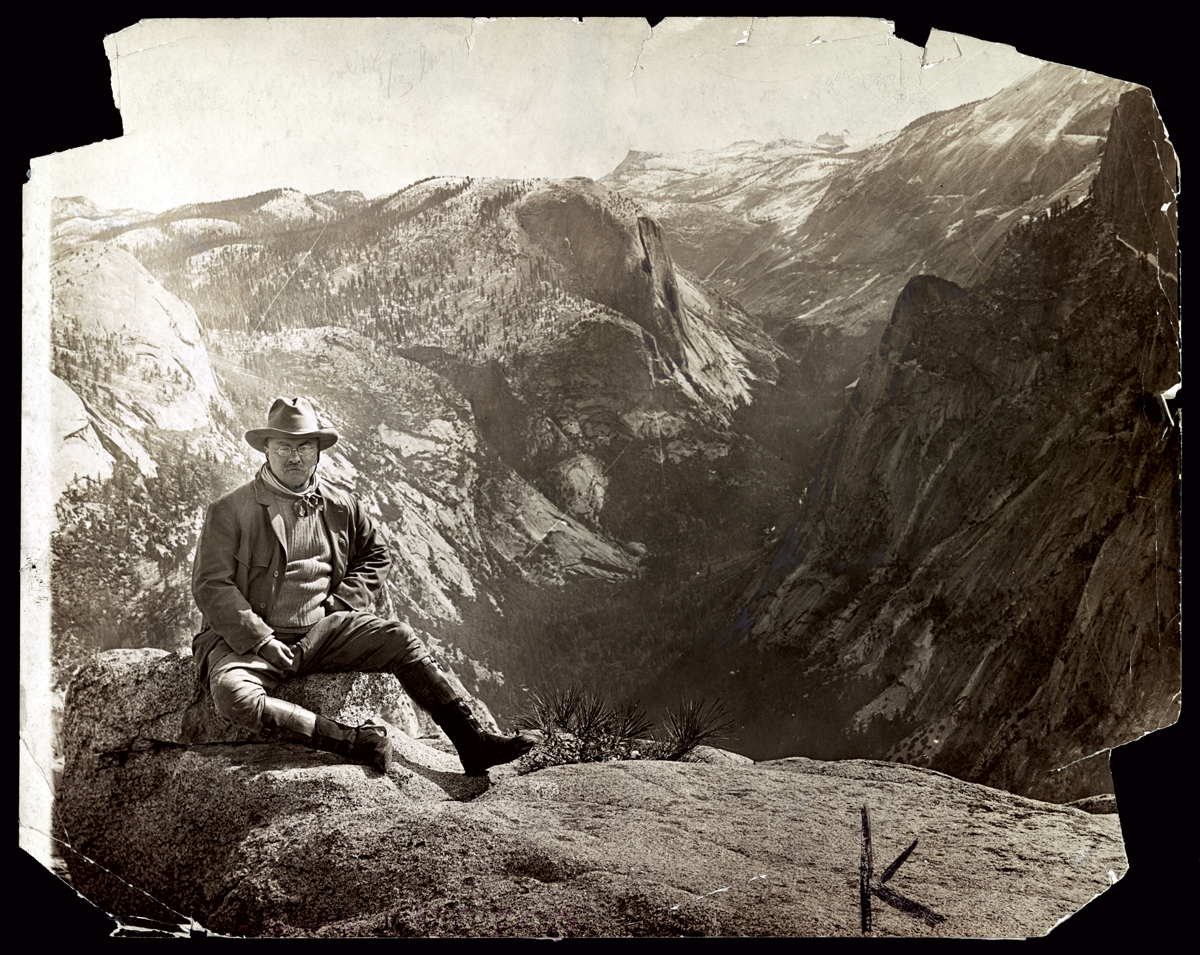

The Hamburg pulled away from the pier, to be escorted across the harbor by a flotilla of gaily decorated vessels, while an enormous crowd cheered, flags waved, and a band played “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Roosevelt, wearing an olive drab military uniform bearing a colonel’s insignia and a military overcoat, stood on deck smiling and saluting with his beloved black slouch hat.

In Naples, the Roosevelts transferred to another German ship, the Admiral. They crossed the Mediterranean to Port Said, steamed through the Suez Canal and on to Aden byway of the Red Sea. They continued on the Indian Ocean and followed the African coast to Mombasa, arriving thereon April 21.The arrangements for the hunt had been made through two of Roosevelt’s English friends who were famous big game hunters, Frederick C. Selous and Edward N. Buxton. Selous had joined Roosevelt in Naples and was with the safari in Africa from time to time. The services of two long-time African residents, Scotsman R. J. Cuninghame and Australian Leslie Tarlton, also noted hunters, had been secured to assist on the entire safari; Cuninghame met the Roosevelts and Selous at Mombasa, and Tarlton awaited them in the interior.

The Colonel appreciated the warm welcome from the lieutenant-governor of British East Africa, but he was anxious to leave for the interior and did so the following day on the railroad that ran inland. So fascinated was he by the wildlife along the route that he spent the daylight hours perched on a seat built across the locomotive’s cowcatcher, enjoying the slow ride through country that was “a very paradise for a naturalist.”

At the little station of Kapiti Plains, 300 miles inland and a two-day trip trip from Mombasa, the safari and Tarltona waited the Roosevelts. It was there, said the Colonel, that his “Great Adventure” really began. “As we drew up at the station,” he wrote, “the array of porters and tents looked as if some small military expedition was about to start . . . A large American flag was floating over my own tent; and in the frontline, flanking this tent on either hand, were other big tents for the members of the party, with a dining tent and skinning tent; while behind were the tents of the 200 porters, the gunbearers, the tent boys, the askaris or native soldiers, and the horse boys or saises (All those numbered about 60, in addition to the porters). In front of the tents stood the men in two lines; the first containing the15 askaris, the second the porters with their headmen. The askaris were uniformed, each in a red fez, a blue blouse and white knickerbockers, and each carrying his rifle and belt. The porters were chosen from several different tribes to minimize the danger of combination in the event of mutiny.”

From Kapiti Plains the safari moved eastward, hunting along the way — zebra, wildebeest, hartebeest, gazelles, duiker, impala, reedbuck, steinbuck, and dik-dik. Roosevelt had specified while planning the trip that it would “not be a game-butchering excursion, but instead a scientific expedition”; no animals would be shot except those needed for museum specimens or food; and that rule was followed. Except for a very few trophies kept by the Rooosevelts, all ended up in the National Museum. The enormous job of preparing skins and bones for shipment to America continued constantly. As the safari moved, the Roosevelts and their companions, on horses, were followed by the longline of burdened porters and four huge, heavily loaded ox wagons, each drawn by a span of seven or eight yoke of the native, humped cattle. The Colonel had as personal attendants two gun-bearers, two “horse boys” and two “tent boys.”

By the first of June, the Roosevelts had reached Nairobi. There the naturalists made the first shipment of specimens to the United States and Roosevelt sent Scribner’s the first four of the 14 articles he would write during the safari. The articles, varying in length from 5,000 to 15,000 words, were published in monthly installments beginning in October1909. They covered everything from his encounters with dangerous big game animals to the “golden joys” of seeing and studying the brightly hued birds, butterflies and flowers.

At night, regardless of how tired he was from strenuous riding and hunting, the Colonel sat on a stool at his portable writing desk and, with a flickering lamp his only light, recorded the events and observations of the day. He had to wear a face shield of netting and gauntlets as protection from mosquitoes. Kermit recalled later, “Father was invariably good-humored about it, saying that he was paying for his fun.” Roosevelt made three copies of each completed article. Keeping one, he sent the other two in blue canvas envelopes, by two different routes, to points from which they would be sent on to Scribner’s.

For six months the safari kept its main headquarters in Nairobi, but made extended trips in all directions, seeking specific animals. Before embarking for Africa, Roosevelt had made a list of 21 animals he most wished to shoot: lion, elephant, rhino, buffalo, giraffe, hippo, eland, sable, kudu, oryx, roan, wildebeest, hartebeest, waterbuck, wart hog, zebra, pallah, Grant’s gazelle, bushbuck, reedbuck and topi. Before the safari was over he had bagged them all — and others. Kermit had done nearly as well. Roosevelt wrote his oldest son, Theodore, Jr., that Kermit had developed into a splendid hunting companion, “a perfectly cool and daring fellow … a bold, skillful rider, always fearless and eager to work.” That very day the boy had stopped a charging leopard at six yards, after the animal had mauled a porter.

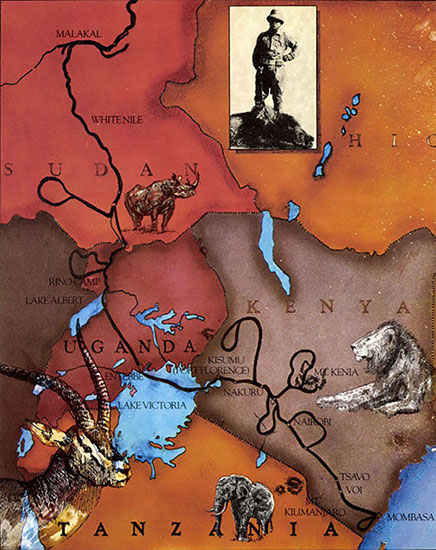

The safari moved from Nairobi deeper into the interior, hunting in the Lake Victoria region and then farther north. On Christmas, the Roosevelts were on the 160-mile overland trek from Victoria to Lake Albert Nyanza, which they reached on January 5, 1910. The remaining two months of their African travels were spent in successful pursuit of the huge, rare, square-mouthed or “white” rhinoceros in the wild, uninhabited Lado country on the White Nile and the giant eland in the Congo. They continued northward on the Nile and reached Khartoum on March 14, where the already greatly reduced expedition was disbanded. The Colonel and Kermit were met there by Mrs. Roosevelt and daughter Ethel.

Teddy Roosevelt and son Kermit with the first cape buffalo taken on safari.

Theodore Roosevelt returned home in June to be honored by the greatest welcome New York had ever bestowed upon a native son. His African expedition had been an unqualified success; it had brought out of Africa a much greater and far more valuable collection than any other expedition and enriched the National Museum with over 11,000 specimens — 4,897 mammals, 4,000 birds, 500 fishes and 2,000reptiles. In addition, it had brought thousands of insects, shells and plants, and a great quantity of zoological, botanical and anthropological knowledge. Many of the species were new to science. Roosevelt had said, “I want Uncle Sam to have a better African collection than anybody else”; he accomplished his purpose.

Roosevelt’s score for the safari was 296 head of big game, including nine lions, eight elephants, 13 rhinoceros and six buffaloes; Kermit’s was 216, including eight lions, three elephants, seven rhinoceros, four buffaloes, three leopards and two bongos.

His collected articles were published in the fall of 1910 as a book, African Game Trails, An Account of the African Wanderings of an American Hunter-Naturalist. It was dedicated to Kermit, “My Side-Partner in our ‘Great Adventure.'” The New York Tribune called it “the book of the year”; the Chicago Record-Herald said it was the very best of outdoor literature, with “action, adventure, the excitement of the chase, and … stirs the imagination on every page”; and the National Geographic, in a six-page review, praised it as “an unusual contribution to science, geography, literature, and adventure.”

An immediate best-seller, it is still regarded as a hunting classic.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in the 1983 May/June issue of Sporting Classics.

Relive Roosevelt’s account of his African wanderings as an American hunter-naturalist. This superb volume includes over 100 photographs. drawings, and maps from the original publication, as well as bonus images not found in other editions. Buy Now

Relive Roosevelt’s account of his African wanderings as an American hunter-naturalist. This superb volume includes over 100 photographs. drawings, and maps from the original publication, as well as bonus images not found in other editions. Buy Now