The first time I saw the 97, I knew where it came from: that era, that time around the turn of the century when men just hunted and really did not ask the question, “Why?” That is simply what they did; you can see it in the eyes of the men in an old photograph from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, standing next to a cross-pole bending with a dozen deer; in the oak-dark oils of a painting of a grouse, a dog and a hunter; in the wagon covered with waterfowl from Chesapeake Bay. You can hear it in the rhythmic words of Roosevelt’s Africa: “Had lunch today beside the carcass of a beast.”

The 97 came from a closer, western, more personal part of that era. I had glimpsed that time and place in my grandmother’s old album, the photos of her early years on the homestead in central Montana. Photos of grandmother in a white blouse, long black skirt and Stetson, holding five sage grouse she’d shot from the sky with the little .22 pump in her hand; of grandfather with a pronghorn, his 99 Savage in the crook of his arm; of friends forgotten and friends known, standing over the body of the last grizzly killed in the Judith Mountains, the mountains that overlooked the homestead.

Everyone in those photographs is black and white, no shades of gray, looking calmly forward into the eye of the old Kodak, no question in their faces: men – and women – had guns and they hunted. They hunted things they ate, they hunted things they felt threatened their life in the wilderness, they hunted things because they enjoyed hunting. It was a way of life, and they never felt compelled to defend it, because no one ever attacked it.

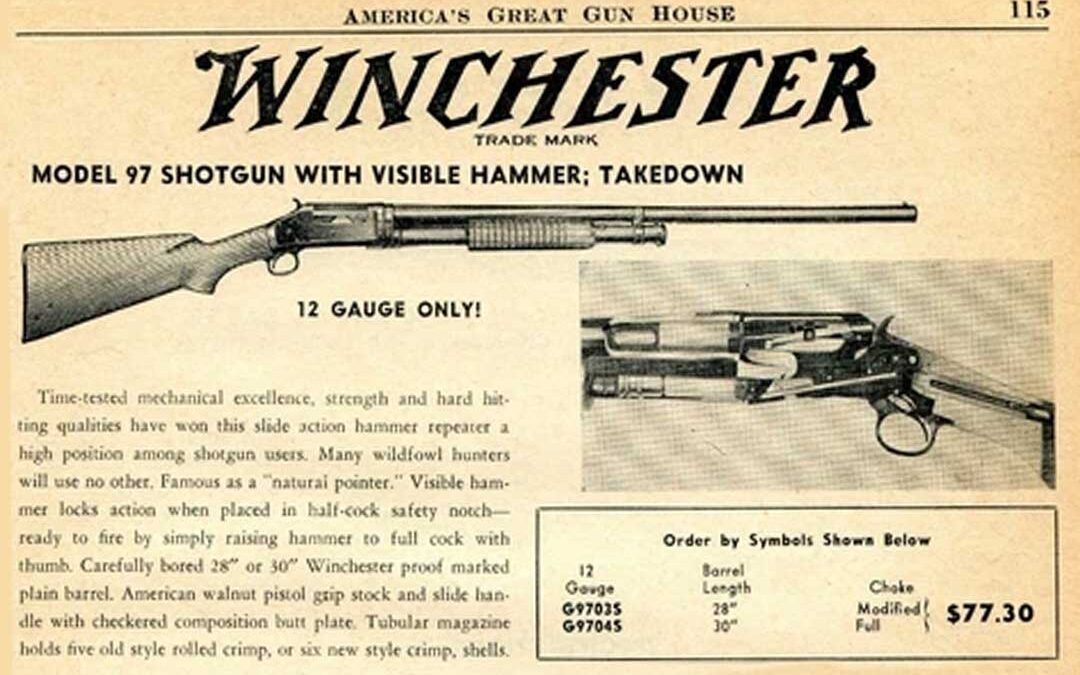

The 97 was almost totally without blueing, the steel the shade of a prairie September thunderstorm, the “Model 1897 Winchester” stamped into the rail behind the forearm losing its sharp edges. The wood was dark, worn by hands, dented by wagon seats and pickup doors, scratched by wild rosebushes and buffalo-berry. It had the same texture as the face and hands of the man who owned it, my wife’s grandfather, a Sioux Indian from the Fort Peek Indian Reservation. I saw it for the first time on my first visit to the reservation after being married, when Ben and I went hunting. We went hunting because that is what men did.

We hunted all day in the grassy hills and badlands of the Reservation. It was mid-afternoon when we came to a patch of choke-cherry, the last berries drying in the sun.

“There’s always ‘chickens’ here,” Ben said, taking the 97 from the gun rack, handing it to me when I walked around the pickup. ”You know how to work this?”

I thumbed back the hammer, then eased it down, feeling the light action of the trigger. I pulled the forearm back, then pushed it forward, moving a shell into the chamber, and eased the hammer down again.

“Yeah.”

We put Ben’s dog into the brush. For a moment we heard her pattering through the leaves underneath the chokecherries, and then there was a time of stillness, just a moment under the prairie sky, before I heard the chatter of birds and the hard burst of wings.

A sharptailed grouse flew from the brush, to my right, and I brought the old shotgun to my shoulder, drew back the hammer under my thumb, with everything moving easily and exactly, as if laid in vectors and intersecting lines. I looked along the barrel as it floated toward the bird, sensing for an instant the enormity of the sky and the smallness of the grouse against it, and then the brass bead on the end of the barrel swept in front of the bird’s flight, a gleaming flight in itself, and the 97 went off without my choosing it to, and the bird left the sky, simply, with no after-moment of feathers floating, and then another bird was up, flying away from me, toward the hill sloping beyond the brush.

There was a consciousness of the action working, the feel of steel sliding against itself, and then the bead was against the bird and another shot sounded through the rush of more birds rising to my left.

I saw the far bird dropping as I turned and heard two shots, saw two more birds falling, and then heard silence. The last empty shell was already in the grass, and the last full shell in the chamber. I looked at Ben.

“Wait,” he said.

The dog ran, unseen, in the brush far below, and a single grouse rose, fighting the leaves with its wings, so far away, angling upward just above the brush-tops, and the shotgun moved again, locked into movement, and then even farther away, so far away I could not believe it, cannot believe it now even in my mind, the grouse fell, its brown wings the color of the cured grass, its falling the curve of the hills. That was all.

Ben drew on his pipe. “Good shooting, kid.” He pulled the pipe from his mouth, looked into the bowl, then tapped out burned tobacco into his hard palm. “But you know, that’s a trained gun.”

He had only that one shotgun – he was from that era, that sepia-toned era, when a man had one shotgun, one big game rifle and a .22 – and over the next three years when I came to visit I used it. He did not. I didn’t bring any of my own shotguns – perhaps because I felt he’d be offended if I did, but perhaps more because I wanted to shoot the 97. He would just stand back and watch me shoot, or drive to the end of a mile-long coulee to wait and pick me up with my load of sharptails.

After that third year my wife and I moved to the reservation. I was beginning to sense that that era, that time I’d seen in those old photographs was at least partially alive there, in Ben and the hills where he’d grown up, and that somehow, for some reason, I wanted to find it, to be part of it, to understand that life. Perhaps it was nostalgia, my memories of my grandmother’s photographs, that drove me, but the desire was there.

So we hunted. We hunted for days, across the open hills, hunted the sharptails in the coulees and draws, hunted white-tailed deer in the badlands south of the Missouri, hunted pheasants and ducks along the sloughs. I learned the pattern of sharptail life across the fall: from the rosebushes along the wheat fields in September, to the buffalo-berry thickets in October, to the short grass along the plateau edges in cold November.

I learned where the whitetail liked to bed and how to push pheasants to the river’s edge and wait there, listening, shotgun held lightly, until the birds could no longer stand the silence and burst up, bright against the snow.

I learned how to pluck sharptails quickly, as soon as they’d been shot, when the feathers were easy to pull from the delicate breast-skin, and how to slice steak from a buck’s hindquarter. That is what I did: I hunted, and took care of the game, and tried to recapture an era, because that is what men did.

It was a cold evening in late November when I went to Ben’s house, to see if he wanted to hunt ducks in the morning. He was in his chair, puffing on his pipe, watching a ball game on television.

“Well,” he said, after I’d asked him if he wanted to jump some farm ponds we knew of, “we’ll have to wait until nine or so. I’ve gotta go to the store in the morning.”

“What for?”

“I’m gonna trade off that old gun.”

“Which one?”

“Oh, that shotgun. I’m getting too old to haul that thing around anymore. It’s too damned heavy.”

I could not believe what I’d heard. “You mean the ninety-seven? You’re going to trade the ninety-seven? For what?”

“There’s a nice little twenty-gauge down there. Real light.”

I shook my head, to myself. I couldn’t comprehend it. He’d told me so many stories about the old gun, about killing pheasants after his hunting partners had missed, about beating the trap champion of North Dakota one time at a Fourth of July picnic. I thought for a moment. “How much did they offer for it?”

He told me.

“Oh, come on. It’s worth more than that.”

“Hell, it’s just a beat-up old gun.”

“You really mean to get rid of it?”

He nodded, his pipe moving up and down.

“Okay, All right. Tell you what: I’ll pay you that much for it.”

His eyebrows came together. “Why?”

“Because I want it.”

He shrugged. “If that’s what you want.”

My wife couldn’t understand my excitement when I brought the old gun home. In reality, I did not consider the gun mine, but a piece of time on loan, something of value that eventually had to be returned. I was sure that Ben would regret his decision, especially when I placed the 97 in the line of guns in my cabinet, its barrel and battered stock saying so much more than the new, sharp lines of the other guns.

We lived three years on the reservation but eventually knew we couldn’t stay there forever. Life was too restricted in the little town; there were other worlds we visited, we wanted. And I also sensed that era I had wanted to capture, to reclaim, had been pushed to its limits, that its last moment here, in this remote part of Montana, was just that: something almost gone, and that perhaps its most valid place was in my mind rather than my life.

We moved to a small city in the mountains of western Montana, and I put the photos of that old life in a shoe box and stored them in a closet: photos of Ben and me next to the pickup, holding two limits of sharptailed grouse, of us next to two hanging bucks, our rifles angled across our chests. Photos very similar to those old photos of the Chesapeake, or the life of the old homestead, except that these were colorful Kodachrome rather than crackled black-and-white.

We visited the reservation early each fall, and I’d hunt sharptails with Ben, and that was the only time I’d use the 97. Its full choke and 30-inch barrel were totally impractical for mountain grouse – and yet that was not the only reason I didn’t use it in the mountains. Something had happened, something had changed: the old gun was almost retired except for that prairie hunt each fall.

And then even those hunts ended. My wife and I separated, a separation much like the separation we’d made with the reservation: we each wanted other worlds. I almost acted on my original feeling then, the feeling I’d had when I first bought the gun – I almost returned it to Ben, but sensed that would seem a plea for the past. Perhaps I would just use it on my own sharptail hunts, wherever they were, as part of the memory of him and an era.

Then one fall the 97 never left the cabinet; I never made it east of the mountains to hunt birds. It wasn’t until the middle of winter, just before a trip to the trap range with two friends, that my hand impulsively took it from beside the new Remington and slid it into a case.

When I walked to the firing line, next to four men wearing vests covered with the patches of competition, carrying new guns equipped with adjustable buttplates and high ribs, and I saw the mountains beyond the trap-house turning pink with evening, a strange feeling came over me, as if the old shotgun and even me, as its carrier, did not belong there on that pad of concrete, between these men dressed in bright colors and tinted glasses.

That feeling was still there, still on the edges of my mind, as I slid a shell into the 97’s chamber, but it eased slightly as I brought the gun to my shoulder.

The clay soared out against the mountains and I swung with it; at the shot and the sight of the clay still sailing, untouched, the feeling returned. There was something wrong; the gun did not feel exact, smooth, the way it had on that long-ago day when I’d stood above a choke-cherry patch with an old man standing beside. In an odd way it was the same feeling, of the shotgun being detached from me, with a sense of its own, but now the feeling was of unwillingness, a forcing that I’d never felt before.

The first five clays went untouched. I wasn’t aware of the other men; their words and shots seemed like something on the edge of a dream. Something I had to move around but not consider. The ninth clay was barely chipped, the first hit, and I tried to concentrate, to find the rhythm of the swing. I broke two in a row, and then everything left again: only three more broke, at uncontrolled moments, during the rest of the round.

As I pulled the last shell from the receiver and walked away from the line, not even looking at the score sheet, I vaguely heard a slight laugh and comment from one of the other shooters. Suddenly I was angry – not at him, not at any mockery of me or my shooting, because I felt so apart from that, but at his smugness, his ignorance of what I held in my hand. I wanted to turn and tell him, coldly, of what the gun had done: of a thousand sharptails against the October sky; of a pheasant dropped far off a across frozen river; of an old man with a face the color of walnut and how men once lived.

I turned and looked at him; he looked away and turned toward the other men. Quickly, with that turning, all the anger drained from me. I stood for a moment, looking at the mountains, then walked slowly to the clubhouse, knowing I might never shoot the 97 again, because what it was and what it came from were gone, and it should not be used in any other way. It was time to put aside illusions and live with memories. They are always much kinder.

Note: The article originally appeared in the 2013 Guns & Hunting issue of Sporting Classics magazine.