The Pearman farm in Wythe County, Virginia, near Porter’s Crossroads, was 798 acres of pasture, small grains and sinkhole hardwoods under the watchful eye of my maternal great aunt, May, and her son, Glen. I called her “Ain’t May” and Glen was “Cousin Glen” and I was 12 years old the summer I was turned loose on the place with a gun. That first summer was barefoot and cut-off jeans and a .22, the worst nightmare the groundhogs on that limestone/ sinkhole and broomsage ground ever dreamed.

As fall approached, I listened intently as the big men talked about the dove field; 56 acres of corn on top of the bluff above the grazing pasture waterhole, where my dad and Glen and their country contemporaries would greet opening day. I worked up my courage and asked to be included but was met with laughter. Dad told me they could not allow a sky-busting kid into the opening day festivities, to spook the birds and detract from the sport. I was crestfallen.

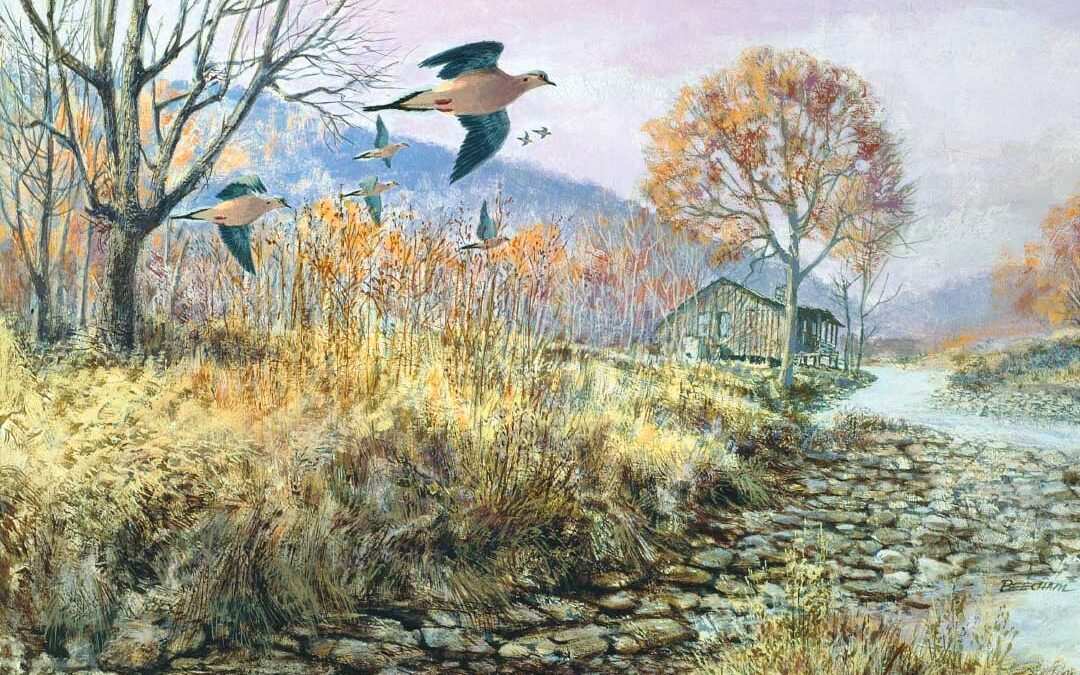

Mourning Doves by Tom Beecham Courtesy of The Remington Collection.

Upon seeing my despondent face, Aunt May prevailed on Glen to do something, and at noon that opening day in the farmhouse yard, as the men loaded the wagon behind the tractor for the trip to the field, Glen uncased his 20-bore Sterlingworth and handed it to me with a new, unopened box of low brass 7½ Peters.

“We’ll drop you at the waterhole,” he said with a wink. “A few birds may drift down that way and maybe you can do some shooting.”

That farm was a kid’s dream come true. I gathered the eggs in the log barn, milked the cow, worked the garden and took care of the ramshackle kennel full of beagles and setters. I watched the old folks make apple butter and butcher hogs, shoe the horses and keep the smokehouse. On warm summer Sunday evenings, I snuck out to hide in the hayloft to watch the chicken fights behind the apple orchard and the big men drink out of mason jars. On Saturday nights they made music on the covered porch, Ain ‘t May on the fiddle and Giles Lefew making the banjo dance, feet tapping and rocking chairs creaking in time. There were rabbits and quail in the buckwheat, squirrels in the hickories, a creek full of trout and a thousand places for a boy to explore. No question: I know what heaven will look like.

I had saved all summer from my hay money to buy two dove decoys and one hen wood duck decoy at Robbie’s Army/Navy store. I don’t have a clue now why I bought the woodie, because we had no ducks and no intention of ever hunting them, but when the tractor stopped and I climbed out of the box into the thistle pasture that September noon, I had them in my arms. The men smiled and laughed and my dad looked a little sick, but I was 12 and carrying a shotgun and a box of shells and all was right in my world. It didn’t matter a whit that no one expected me to fire a shot, except perhaps at some errant killdeer. Ignorance is bliss and in my youthful confidence I was completely blissful.

The tractor and wagon labored its way up the dirt track over the bluff and out of sight, above me and across the little branch. That pathetic dribble of limestone water fed the pond, then leaked out from the dam near the base of the cliff to continue its ramble to the New River. The waterhole was a manmade mudhole about a half-acre in size and about four feet deep, the bare soil and gravel banks humped up with a backhoe, with a couple of ancient locust trees thrust indignantly through the hard-packed red dirt. It was a stinking muddy crater in a thin pasture overgrazed to a few clumps of fescue and scattered thistle, but to me it looked like the promise land.

I rested my shotgun, broken open, over the trunk of a fallen locust near the root-ball at the head of the pond and clipped my dove decoys onto a dead locust branch, which I shoved up against the root ball above my chosen blind.

I fished a 20-foot length of put-together bailing twine out of a jeans pocket and tied one end to an exposed root and the other end to the neck of the duck decoy, and tossed it out onto the brown water, where a slight breeze kept it away from the cowshit-splattered shore.

I squeezed into the crook of the root-ball and trunk, opened my shell box and loaded my gun. Those wonderful waxed paper hulls slid perfectly into the breech of each barrel; the gun snapped shut like only a Fox can and I was ready.

I had fired a shotgun before, horribly, at clay birds thrown by Dad as he tried to coach me with his ’58 Remington 20 gauge. I took 42 shots without even chipping a disk, and as we retired that evening to the house, he sympathetically patted my shoulder, saying that maybe someday, with sufficient practice, I would be able to bird hunt.

The gun was a foot too long for me in pull and most of the time when I fired it the butt was under my armpit and my trigger-hand thumb bloodied my nose. I hated and loved it at the same time.

I had seen Glen’s Fox on several occasions and even had the chance to shoulder it once before that faithful day, and I remember it came to my shoulder and cheek like beggar lice come to flannel. I wanted it so bad I could taste it.

To now be in charge of it, alone, was almost enough to make the day a success. Before God, a few hundred thistles and three Hereford steers, I swore on all that is Holy that today I would shoot it well.

The September sun beat down on my shadeless retreat and soon I could hear the booming of the guns up over the bluff. With my sweating hands gripping the little double, I was absorbed in thought when the melodic whistling of two doves landing in the locust froze me like a statue. I raised my head as they hushed from behind me and the gun came up of its own accord, and suddenly I was holding an empty shotgun and two doves were lying dead on the pond, a few feathers floating away on the breeze. I don’t remember pointing, pulling the triggers, swinging, nothing.

Dad’s voice sounded in my head: “The best wing-shots…they don’t aim, they don’t think, they just shoot. It has to come on its own; you can’t force it.”

I dropped the empty hulls at my feet, stuffed two more rounds in the gun and literally bristled with impatient anticipation.

The birds flew that day; the shooting on the bluff was continuous and I could see them, rhythmic wingbeats on dots in the distance. They tempted me out of range; they circled and watched and teased. Killdeer, robins and starlings surprised me, a dozen false starts and muttered curses under my breath. The doves were there; I begged and wished and prayed them to me.

It had been a hot, dry summer, a drought really, and I didn’t know then what water meant to doves. This stinking sump on the scorched pasture, so close to the bounty of the cut corn, was the only real water within miles. The birds had plenty to eat; I didn’t know that it was water they craved.

In twos and threes they came, floating down to the safe waterhole, to be met by little clouds of fine shot. As the afternoon wore on and the shooting on the bluff above intensified, the birds came to false sanctuary, for water and gravel and rest, and I rewarded them with death.

As the sun approached the treetops I took stock: 17 dead doves ringed the shoreline and at my feet lay 18 empty Peters hulls. The sweat made brown rivulets down my sunburned, dusty face, and my grungy green tee shirt clung to my skinny chest. You couldn’t have lured me away from that spot at that moment with a thousand-dollar bill.

Suddenly the quiet hum of the afternoon was shattered with the plaintive cry of six wood ducks as they tore low over me from behind, the formation breaking left and high beyond the dam of the pond, turning 180 degrees and bearing back down on me face-on. Twisting, turning, whistling, coming, I saw them behind the ivory bead as bunched up and jockeying for position, they dropped their landing gear, and I pulled the front trigger, the recoil causing my middle finger to instantly pull the rear. Three drakes and one hen cartwheeled into the pond around my decoy throwing muddy, stinking water into the air. I almost peed my pants.

The shooting on the bluff was sporadic now and the woodies had drifted to the far shore. Four doves surprised me from the shadow of the bluff beyond the pond and approached from right to left. The Fox found my shoulder and cheek and as I passed the lead bird it fired, the bird stopping in midair amidst a cloud of feathers, then I swung back to the right to catch up to a retreating survivor. The left barrel let go and now he too found the muddy water.

Nineteen doves and four woodies littered the pond and muddy shore and scattered around my feet were 22 empty hulls. Three shells left. I reloaded the double and wiped the sweat from my eyes.

I was watching six doves as they landed in the thistles beyond the pond when the sound of ripping linen brought me around; two blue-winged teal strafed my position, low on the water, and they also turned up and back, bearing down on my decoy. I flared them when I stood, and I distinctly remember leading them too much and the gun going off twice anyway, and my absolute joy at the rear bird crumpling into a feathered pinwheel that pounded into the dirt ten feet to my left.

The ruckus raised the doves in the thistles, and as they came up and circled the pond, I was frantic in shucking the empties and stuffing my last shell into the right barrel. All but one broke left out of range and the last, the suicide, drifted over as the tractor and wagon made its way down the bluff trail. I aimed, stopped my swing, thought of my Dad watching instead of the shot. My shot might as well have been into the water at my feet, the dove beating a hasty retreat.

The tractor stopped near the gate across the pasture and Dad and Glen came walking up, Dad saying with a fatherly smile, “We saw you miss that last shot. Do you have any shells left?” “No,” I answered, humbly puffing out my narrow chest, “but I could use some help picking up the birds.”

Laid out on the gray weathered boards of the wagon, in front of eight men, Dad and Glen, shaking their heads and grinning like ‘possums, counted the birds and shells.

Glen said, “Nineteen doves, four woodies and a teal, with twenty-five shots. I believe that’ll do. Maybe next time, you’ll sit with me!”

Everyone who hunts can look back on some memory, some day in the past, when the gun, the game and the circumstances came together to make an unforgettable moment. All of us at that young age searched for the one thing we could do well; ahead of me that day was love and loss, joy and tragedy, hits and misses, but for the first time that one afternoon and forever after, I knew without doubt that I would be a hunter.

It has been nearly 50 years since that September afternoon; that kid grew up, raised a family and hunted the world. And every single time I’ve handled a shotgun, from that day to this, I have thanked God for my Dad, a Fox double and a muddy Wythe County waterhole where a 12-year-old boy found his place in this world.

A superb collection of stories that captures the very soul of hunting. For hunters, listening to the accounts of kindred spirits recalling the drama and action that go with good days afield ranks among life’s most pleasurable activities. Here, then, are some of the best hunting tales ever written, stories that sweep from charging lions in the African bush to mountain goats in the mountain crags of the Rockies; from the gallant bird dogs of the Southern pinelands to the great Western hunts of Theodore Roosevelt. Great American Hunting Stories captures the very soul of hunting. Buy Now

A superb collection of stories that captures the very soul of hunting. For hunters, listening to the accounts of kindred spirits recalling the drama and action that go with good days afield ranks among life’s most pleasurable activities. Here, then, are some of the best hunting tales ever written, stories that sweep from charging lions in the African bush to mountain goats in the mountain crags of the Rockies; from the gallant bird dogs of the Southern pinelands to the great Western hunts of Theodore Roosevelt. Great American Hunting Stories captures the very soul of hunting. Buy Now