With the grouse moors covered in blooming heather, it’s once again time for the annual Sport of Kings: driven grouse shooting.

With its abundance of heather and red grouse, Yorkshire’s undulating moors echo with gunfire each August as artfully engraved shotguns costing as much as a starter home intercept grouse as they have since George III sat on the throne. It is an annual ritual celebrated by top-of-the-food-chainers who relish the rarified air of the sport and who enjoy shooting a truly wild bird with a life force so strong that it will not succumb to domestication. The classic European shoot will, for a few days, give you the sense that you’ve arrived, as if the glass slipper fit and you’ve been invited to the ball through providence. That feeling lasts until you receive your final bill, anyway.

Greeting me on my baptism to the activity is Alex Maiden and Will Criddle of Criddle Field Sports, a company that brokers and arranges all manner of shooting opportunities across the British Isles and throughout the European mainland. In other words, they trade in addictions as the kind of events they sell are something of a narcotic for the double gun crowd in need of a regular fix of burnt powder. Both are affable sorts who, for this shoot, are juggling a mixed line originating from Ireland, France, England, South Africa and, of course, America.

It is a perfect morning for grouse, the heather is in full bloom and gamekeepers are reporting an abundance of birds. If you’re going to shoot driven grouse for the first time, you might as well arrive during optimal conditions. The group consists of 10 gunners each with a loader. The shooters stretch across a piece of the moors in a line, perhaps 50 yards between each. On the other side of the moor—roughly a mile away—is a line of beaters and their dogs who will walk toward the guns and flush the grouse to the awaiting shooters. Each shooter has two guns—one always in operation with the loader prepping the second gun for quick deployment after the first gun’s two barrels have both been fired. The idea is to maximize a shooter’s opportunities to fire at grouse. This form of shooting dates back to the late 1800s with the advent of breech-loading shotguns and cartridges, the successors to muzzle-loading guns whose powder, wad and shot pellets had to be packed individually after every firing.

Driven grouse shooting originated as the sport of royalty in the late 1800s and continues across The British Isles to this day. SCOTT WICKING, CRIDDLE FIELDSPORTS

Of all the driven shooting offered on this planet, grouse on the Scottish and English moors is the most celebrated, like golf at Augusta or St. Andrews. Good years for grouse production are something akin to wine vintages, some are better than others, so when the conditions are optimal, savor it for the bounty that it is. That is exactly what I intend to do.

I arrive to our first moor, the sweeping hills of heather looking like they need a yellow brick road to take us to the Emerald City of Oz. To think one of the world’s great game birds originates in such stunning cover partly explains the allure of August and September on the moors. The other is the sheer brilliance of the bird that flies in flocks, roller-coastering over the undulating terrain with ever increasing speed as they scream downslope with the boost of gravity.

As the first birds of the beat head my way, I can see them hundreds of yards out. I repeat the mantra of two shots out front, change guns, and take two behind. Every muscle in my body is taught, like I’m a jack-in-the box waiting to spring from the stone butt and introduce my Beretta Italian doubles to these most British of birds. Seconds seem like minutes and, despite plenty of time to prepare, I underestimate the speed of the birds and come up too late. I fold one bird out front and nearly screw myself into the ground trying to catch up to a second bird as the flock rockets overhead. The faint call of the birds sounds strangely like a chuckle, which seems appropriate given my drunken pirouette.

A pair of premium Beretta over-and-under shotguns are good medicine for the fast flying grouse. SCOTT WICKING, CRIDDLE FIELDSPORTS

Upon careful inspection, a red grouse looks very much like a ptarmigan that hasn’t yet exchanged its dark plumage for its ermine coat of winter. The birds are closely related. And like grouse the world over, they’re extremely wild. While pheasants and partridge are perfectly content to be raised in captivity, grouse will have none of it. Their habitat can be managed and their predators controlled, but that is as close to domestication as they will accept. The rest is up to Mother Nature and the weather conditions to determine what kind of fall flock will exist amid the heather.

If the first beat is any indication, the reports of good numbers of birds throughout the Yorkshire moors isn’t fake news.

“You were in a good spot,” says Joe Clayton, a premium Beretta collector from Indianapolis, as we head to the next beat. “How far were you leading those birds?”

“Mostly not enough,” I offer. “I think I’ll try missing in front from now on.”

The second beat takes us to a place with steeper terrain, the hills rising higher and falling farther than the previous drive, which means even more challenging shooting. Instead of the birds hugging the ground as they whisk their way downslope, they tower high overhead as they gain speed. It is very different shooting than what the first beat delivers, yet another of the charm found with driven grouse and the varied land they inhabit.

A field lunch brings shooters together to celebrate this top-of-the-food-chain experience before more afternoon driven grouse beats. SCOTT WICKING, CRIDDLE FIELDSPORTS

While many grouse shots can be low—much lower than pheasants and partridge—swinging with ground behind a bird is unnerving to many first time grouse shooters because the general rule is always to make sure there’s blue sky under a bird for safety’s sake. Shooting a beater is considered poor etiquette and tends to shorten the duration of your stay. When firing at grouse, it’s about understanding where the beaters are and stopping your swing before crossing them with gun barrels.

My beat is slow, so I mostly watch a father-son tandem from South Africa take turns sharing a butt as they make the most of their opportunities. Farther up the line, Clayton finds himself in the thick of the drive with the greatest volume of birds coursing over his end of the line. There is a poetry to watching skilled driven shooters time their rise, swing and shoot along with their transfer to the second gun. There’s a groove to the cadence when a shooter and his guns and loader all come together to execute with precision.

And when you do that, you’ll be King for a day. The final bill be damned.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow Sporting Classics TV host Chris Dorsey at Forbes.

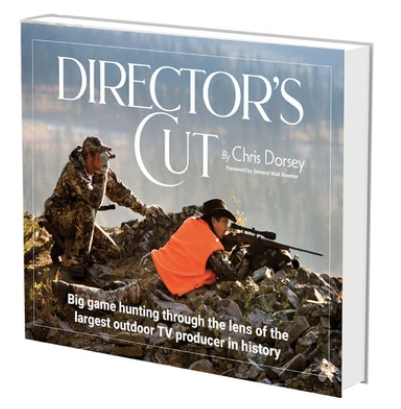

The World Of Sporting Literature Has A New Classic from one of the planet’s most widely traveled hunters. Director’s Cut…Big game hunting through the lens of the largest outdoor TV producer in history, is a book and film production more than 15 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of big game hunting.

The World Of Sporting Literature Has A New Classic from one of the planet’s most widely traveled hunters. Director’s Cut…Big game hunting through the lens of the largest outdoor TV producer in history, is a book and film production more than 15 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of big game hunting.

Dorsey has spent the past 25 years investigating and chronicling the animals, people and unforgettable places home to remarkable big game hunts while producing nearly 60 outdoor adventure television series. In the process, his teams amassed a library of more than 100,000 hours of HD footage and nearly 150,000 photographs, making Director’s Cut (the book and DVD) an unmatched celebration of the world of big game hunting. Buy Now