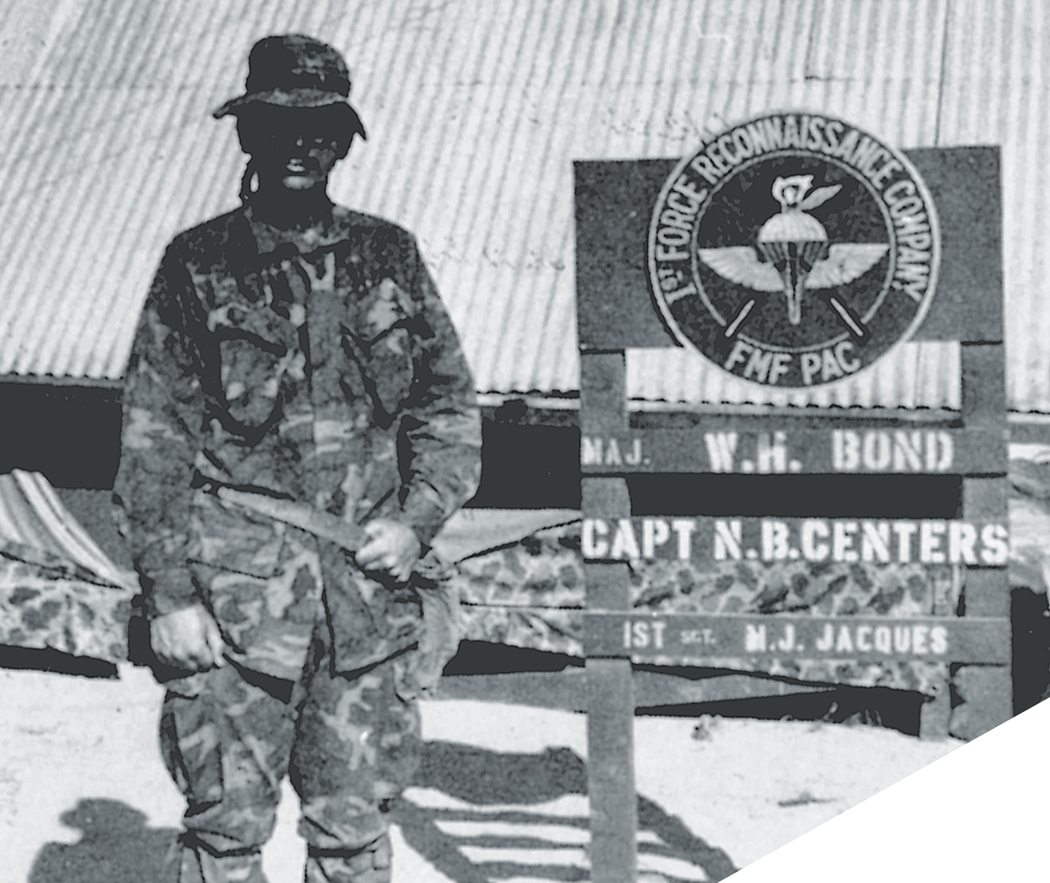

As a Marine deployed to Southeast Asia 25 years ago, I had heard of tiger sightings in the bush, even an incident in which a Marine had been killed by one. I never ran across anyone, including intelligence people, who could verify this, as most unit reports and maps were classified at that time. Some months ago I found the incident in Bruce Norton’s account of his time with 1st Force Recon. It is the only documented case of that attack I have seen.

By 1970 U.S. operations in South Vietnam had become so effective that continuous reinforcement of combat troops was required by the North Vietnamese enemy. Since the narrow northern border, the DMZ, was demarcated by the Ben Hai River and rolling, open country, it would have been impossible for the North Vietnamese Army to access large units undetected. Their preferred travel corridor was the trail complex running south through Laos and Cambodia known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Along the trail, the NVA could move in relative safety before entering South Vietnam through many remote access points along her western border.

One in particular was an enormous, tree-covered basin called the A Shau Valley. Because of its size and cover, the A Shau Valley became a staging and logistics area for thousands of NVA troops. To counter them, U.S. Marines inserted (by helicopter) small, usually six-man reconnaissance teams to report enemy activity and call in air strikes. Thirty miles from the nearest friendly units, these recon teams normally spent five to seven days observing and patrolling before being extracted.

The A Shau Valley was a wilderness of rugged mountains, dense jungle canopy, crystal streams, and waterfalls. Unlike the cultivated piedmont areas to the east, inhabitants were few. Animal life, however, was abundant. Deer, wild pigs, and small apes lived in the A Shau and, since imperial times the valley had served as a principal hunting area for Bengal tigers.

Sergeant Robert C. Phleger had joined 1st Force Recon initially as a radio specialist and later as an assistant team leader. With his considerable leadership ability and bush skills, Sgt. Phleger was soon made leader of his own recon team. Cheerful and possessed of a wry sense of humor, Sgt. Phleger earned an outstanding reputation for developing the expertise of his men.

In April of 1970 Phleger flew to Hawaii for a hard-earned R&R and married his high school sweetheart. Shortly after his return to Force Recon, his team was slated for a five-day mission of reconnaissance patrols in the A Shau Valley. Having just returned from his R&R, and with not much time left in-country, Sgt. Phleger was instructed to not go out with his team. Since the mission was relatively easy, Cpl. Jerry Smith could take over as team leader.

Ever the professional, Sgt. Phleger refused, insisting to his lieutenant that he needed to accompany his men in the leader transition (this type of devotion to unit was common to Marines of that era). The lieutenant finally agreed, with the understanding that this was definitely Sgt. Phleger’s last trip into the bush and a safer job in the rear would be waiting upon his return. And so, Sgt. Phleger took charge of his seven-man team.

On the afternoon of May 5, 1970, the team was inserted near Razorback Ridge, so named for its height and 65-degree slopes on both sides. The team spent most of the day climbing the ridge; once on top, they set in for the night. Since the ridgeline was extremely narrow, there was no room to place the men in their usual 360-degree defensive position, so Sgt. Phleger stretched them along the ridge with himself farthest out.

Sometime after dark the team members on watch heard “a sudden rushing movement in the dense brush, accompanied by several short muffled screams from Sgt. Phleger.” The men radioed their lieutenant, who told them to stay alert; it was possible Sgt. Phleger had only experienced a nightmare and, awakening disoriented, wandered off into the brush. In the dark night, the men sat listening. Originally no more than five feet from the nearest team member, Sgt. Phleger had disappeared.

Had he been discovered and killed, or captured by some silent, stalking NVA soldier?

Deep in enemy territory, the men could not call out his name or give away their position with a flashlight. Several team members crawled to the sergeant’s last position and felt for him in the darkness. Finding nothing, they crawled back in place and remained on “one-hundred percent alert,” weapons ready.

At daylight the soldiers found Sgt. Phleger’s rifle and other gear where he had placed them. Slightly farther out, they found his hat and poncho liner—soaked in blood—with drag-marks leading down the ridge to heavier brush. Suspecting they were being drawn into an ambush, Cpl. Smith radioed in and was told to follow the drag-marks.

They did so and, though all had seen casualties before, none were prepared for their macabre discovery.

Sgt. Phleger’s body had been completely devoured from the waist up. The team was attempting to radio when they were startled by the earth-shattering roar of a tiger less than 15 feet away. Several Marines fired their weapons, but the tiger, which had obviously been lying close by and had stood up to defend his kill, fled the scene unhit. Cpl. Smith radioed in the situation and was told to prepare for immediate extraction. As they gathered their gear, the tiger returned, this time positioning itself between the men and the sergeant’s remains. Again, the men fired at the cat as it slipped away. One team member hurled a fragmentation grenade in the direction of the fleeing predator, but it was never determined whether or not the animal was hit. Once in the rear, an autopsy determined that the tiger had seized Sgt. Phleger and broken his neck. Mercifully, he was dead before the tiger had begun eating him.

Several days later, a recon team from a different unit awaited extraction from another area in the A Shau Valley. The big CH-46 helicopter landed, dropped its ramp, and the team rushed aboard. Then assistant team leader, Sgt. Michael Larkins, hung back on one knee to avoid the prop blast, making sure all men were on board.

From inside the aircraft, several team members suddenly noticed movement behind the sergeant. Since verbal communication was impossible over the screaming turbines, the men signaled to Sgt. Larkins to turn around. He did so, raising his weapon, and saw a tiger charging him! Sgt. Larkins fired a round toward the cat’s head. The shot turned the animal broadside and Sgt. Larkins quickly emptied his magazine. The tiger fell dead less than 15 feet from Larkin’s position by the ramp of the aircraft.

Anyone familiar with helicopters and the deafening noise and virtual windstorm they create when landing has to be amazed at the audacity of this tiger. A CH-46 is a large transport helicopter with a span of more than 90 feet needed to clear its front and aft blades, which in Larkins’ case, were turning with enough power to flatten the surrounding grass. If a tiger wouldn’t be afraid to charge in this situation, just what would it be afraid of?

The men retrieved the cat and flew it back to the rear. Later, it was determined that the 300-pound tiger was not the same one that killed Sgt. Phleger. No wounds or marks were found on its body, and the sergeant’s man-eater was described as being larger in size.

The two teams had been operating some miles from each other, but I do not believe that to be a major factor. North American cougars, for instance, have been known to travel hundreds of miles in a short time. It seems likely that it was the same cat, possibly a wounded animal or one that associated men with food. Perhaps the medical examiners had failed to notice shrapnel embedded in the tiger from the grenade, and that Sgt. Phleger’s men never got a good enough look at the tiger to judge its size accurately? Most dangerous animals appear very large when seen for the first time.

The incident remains a mystery, and for the duration of the war there were no more reports of tiger attacks on American servicemen

Note: Ken Kirkeby’s article originally appeared in the January/February, 2002 issue of Sporting Classics.