The wind howled and the temperature plummeted as Martha and I stepped into Captain Rick’s skiff at Willis Wharf, Virginia. It was April 2016, and I had hoped for better weather, but light snowflurries the day before had us dressed appropriately. Richard Kellam had promised to fulfill a four-decade-long dream of mine and take us out to explore Cobb Island. No foul weather could dampen my enthusiasm, and there was no one better than Rick to guide us to Virginia’s barrier islands.

Captain Rick, who is U.S. Coast Guard licensed, does historic and eco-tours, and has authored and coauthored books and articles on the barrier islands. His home is a treasure trove of antiques and memorabilia representing the past history of Virginia’s coastline. Finally, the day arrived. The outboard roared to life just as the sun came out over a cloudbank on the eastern horizon. We were on our way.

I first became interested in Cobb Island decoys when I bought a shorebird made there in the late 1800s. That was 45 years ago, and since then, I have researched everything I could find about the Cobb family. Fortunately, there is ample information and artifacts available to piece together this wonderful story.

The Cobb family came from a long line of seafaring individuals. Nathan Sr. was born in 1797 in Eastham, Massachusetts. He prospered with his father, Elkanah, in the family shipbuilding and freighting business. In 1820, he married Nancy Doane. She suffered from poor health, probably tuberculosis. In an effort to improve Nancy’s longevity, Nathan adhered to her doctor’s suggestion and decided to move south to a warmer climate.

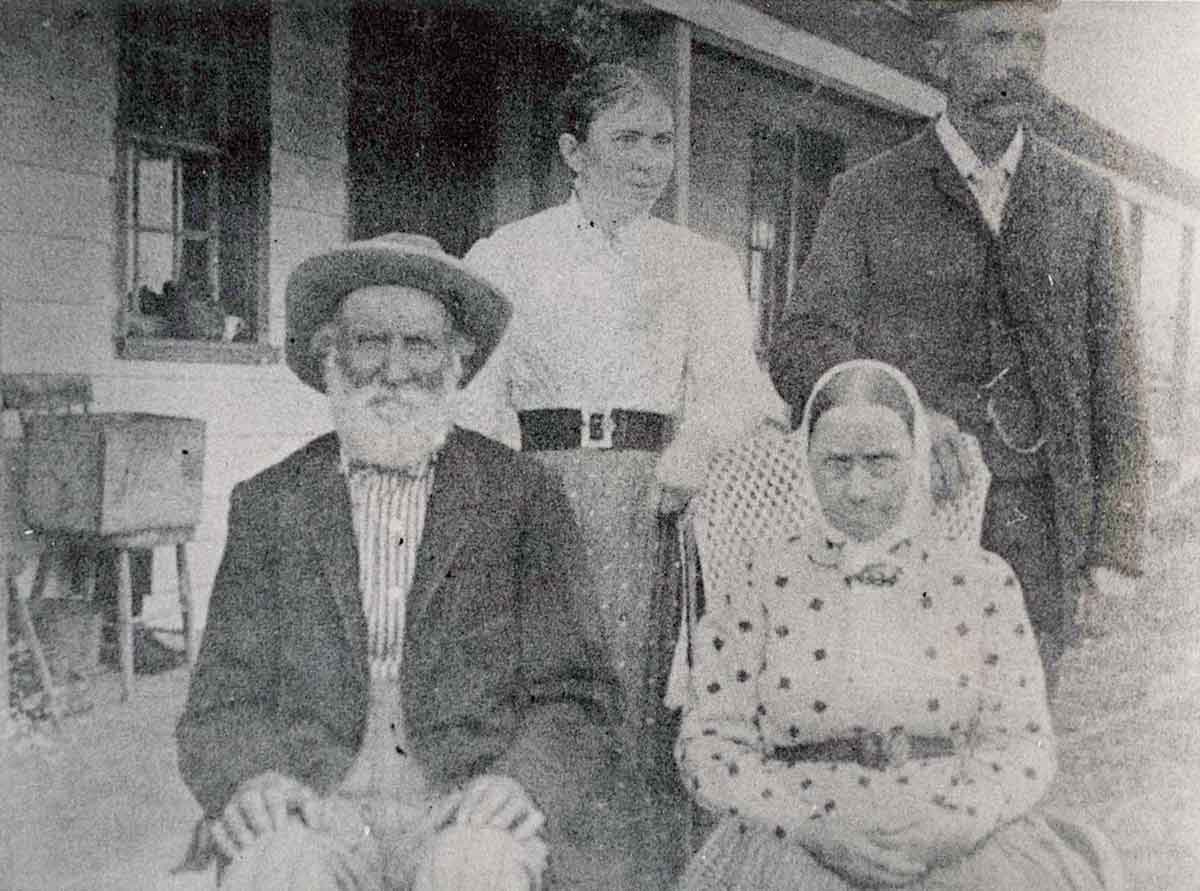

Nathan Jr. and his wife, Sally. Standing are Nathan’s son, Elkanah, and his girlfriend, Annie Wyatt. They are in front of Cobb’s Hotel in 1885.

From 1940 interviews with Lucius and Arthur Cobb, grandsons of Nathan, we learn that he had discovered the Virginia coast on an earlier freighting trip. He was impressed with the resources the land and sea offered and envisioned a fresh start there.

Nathan sold his share of the business in 1837, bought a schooner, and loaded it with the essentials his family would need, including lumber for a new home. He then sailed south with Nancy and his three young sons: Nathan Jr., Warren, and Albert. A storm forced them to seek shelter in a small creek near the village of Oyster on the seaside of the Eastern Shore. The local folks were friendly and helpful to them, and Nathan decided to settle there. He built a modest home and a small store in Oyster, but within two years he became bored with shopkeeping.

Nathan was a seafaring man and wanted to be closer to the open ocean. He had started a salvage business along several barrier islands where ships often ran aground in storms. Nathan also hunted in these waters, particularly the area around Great Sand Shoal Island. Only eight miles by water east of Oyster, the barrier island had a beach several miles in length, an area of dunes down the center, and an apron of salt marsh meadow on the western backside. Not much to hang a hat on, much less a home, but Nathan liked it.

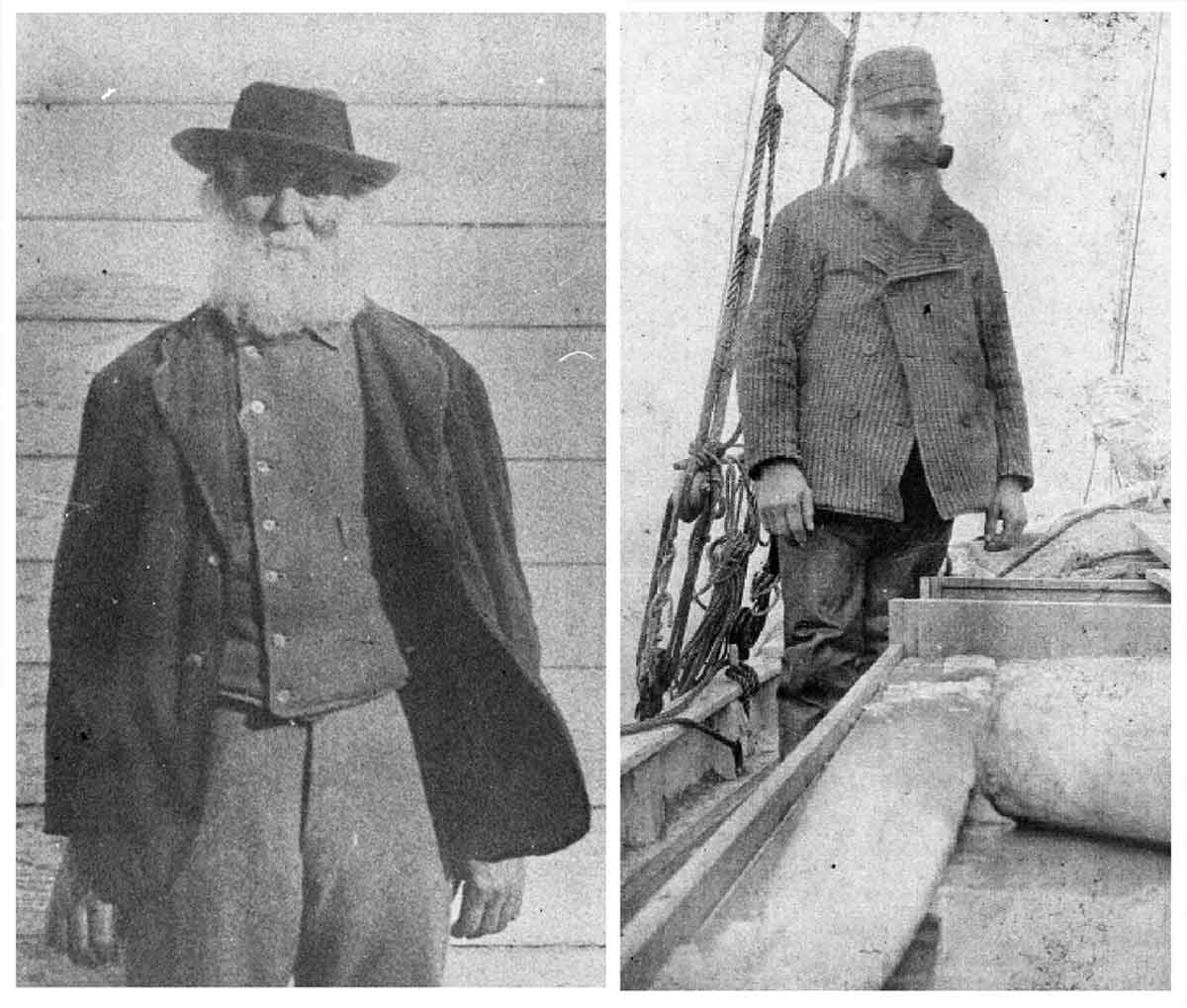

Nathan Cobb Sr. with his favorite shotgun, a double barrel 8-gauge, sometime between 1875 and 1880.

The widely accepted story is that Nathan discovered a brown liquid seeping from the beach sand. He guessed it to be salt, a highly valuable commodity in those times. His hypothesis was proven true when he boiled the liquid and produced salt. The island was owned by William “Hard Time” Fitchett, who did not regard it highly. In 1839, Nathan purchased Great Sand Shoal Island for $1,050, his profits from the ship-salvage business, and a quantity of salt. He decided to move his home and family to the island to be closer to the salvage business that was proving to be quite lucrative. It was a massive undertaking, and in those times a precarious one. He built his home at the rear of the sand dunes on the edge of the marsh. The man definitely had his share of nerve.

Although Nathan didn’t know it at the time, his gamble would prove fortuitous. The littoral currents and sand-sharing systems of the area—Hog Island on the north and Wreck Island on the south—were expanding Cobb Island, as it was now known, in length, width, and elevation.

Nancy’s health continued to deteriorate and she died in 1840 shortly after the family moved to the island. Nathan remarried Esther Carpenter, who for 22 years was a good wife who fit well with life on the Island. Nathan’s three sons joined their father in the salvage business, which became more and more successful. They became quite adept at reading the tides, currents, and wind, which enabled them to save many ships and countless lives. It was an acutely dangerous business, but they were good at it.

Each of Nathan’s sons married and built homes on the island. Nathan Jr. married Sally Dowty and had one son, Elkanah. Warren and his wife, Emily Roberts, had three sons: George, Arthur, and Henry, and a daughter, Eva. Albert married Ellen Doughty, and they had two sons: Thomas and Lucius, and a daughter, Addie.

A shorebird gunning party on Cobb’s Island in 1892. Elkanah Cobb is seated second from left.

Oysters, clams, and crabs were plentiful in the waters around Cobb Island and the fishing and waterfowl hunting was nonpareil. The Cobbs were excellent shots and Nathan Jr.’s marksmanship became widely known. Brant, geese, black ducks, and scaup were harvested by the thousands in fall and winter followed by shorebirds, mostly curlew and plover, in the spring. They would clean the birds and pack them in barrels to be transported on passing ships to markets in Baltimore and New York.

Cobb Island, with all its salt meadows and eel-grass flats, sat squarely in the migratory route of innumerable shorebirds and waterfowl, especially brant. Stories of the wonderful shooting the Cobbs enjoyed soon spread up the coast. Wealthy sportsmen began contacting the family, and some of them were taken out to experience the fantastic shooting. The Cobbs realized there was money to be made and quickly increased the number of “sports” they were guiding.

Along with the increase in hunting clients came the need for comfortable blinds, additional guides, boats, and good decoys. Several members of the Cobb family carved shorebird and waterfowl decoys, the most notable being Nathan Jr., Elkanah, and Arthur.

Nathan Jr. had a talent for creating lifelike decoys, both shorebirds and waterfowl, especially brant. Most of the decoys made on Cobb Island were probably crafted from just after the Civil War until 1890. These two decades witnessed the peak of sport gunning in America as well as on the island.

This curlew and brant were created by Nathan Cobb Jr. Estimated value of the curlew is $65,000 and the brant, $80,000-$90,000.

All Cobb decoys are highly coveted, and today, with prices reaching six figures for some of the better ones, there is much debate as to who made each bird. We will likely never figure it all out. Nathan Sr. probably made a few, but there is no obvious evidence that he carved.

Many of the brant have solid bodies, some fashioned from ship masts. The carving on these birds is less refined, as is the painting. A few of them with a straight “N” carved in the bottom might have been made by Nathan Sr.; others might have been the earlier work of Nathan Jr.

Most of the later brant, geese, and ducks made by Nathan Jr. were hollow-carved and had glass eyes. The heads on all of his ducks are inletted, exhibiting superior skills and creating a stronger decoy. But his greatest achievements are his hollow-carved brant and geese.

Left: Nathan Cobb Jr., circa 1892. Right: Elkanah Cobb on his sloop in 1893.

Nathan Jr. would scavenge driftwood, particularly the contorted limbs of maritime holly and myrtle, which were twisted in a variety of shapes. He could visualize the necks and heads of brant in many positions—feeding, fighting, swimming, and resting. A rig of his decoys would resemble real birds better than those of any other decoy maker.

Grayson Chesser, who lives on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, has been making working decoys and guiding hunters most of his life. He is also an avid student of the shore’s fowling history and the decoys that were a part of it.

Regarding Nathan Jr.’s skills, Grayson stated: “He was arguably the greatest decoy maker who ever lived. His carvings have more life than the decoys by any of the other masters. The true test of an artist is not measured by the amount of detail invested in a carving, but rather how little is needed to capture the essence of a bird. Nathan Jr. could make wood live and breathe.”

Several of the guides who worked for the Cobbs also helped to produce decoys. Walter Brady, John Haff, George Isdell, and Eli Doughty all produced wonderful birds that have become highly prized among collectors.

Nathan Cobb Jr. carved this brant decoy around 1875. It was used by his son, Elkanah, who branded the bird with the initial “E.”

The real prize is to find a Cobb decoy with an identifying brand on the bottom. Nathan Jr. carved a serifed “N” on the bottom of most of his birds, and he may have carved the “E” that we find on other decoys, which he made for his son, Elkanah. Nathan’s son, Elkanah, and his brother Albert, branded many of their own decoys with their name, i.e. “E.B. Cobb.”

No matter who made it, any decoy identified as a Cobb Island creation carries all the history and lore with it and is a piece to be treasured.

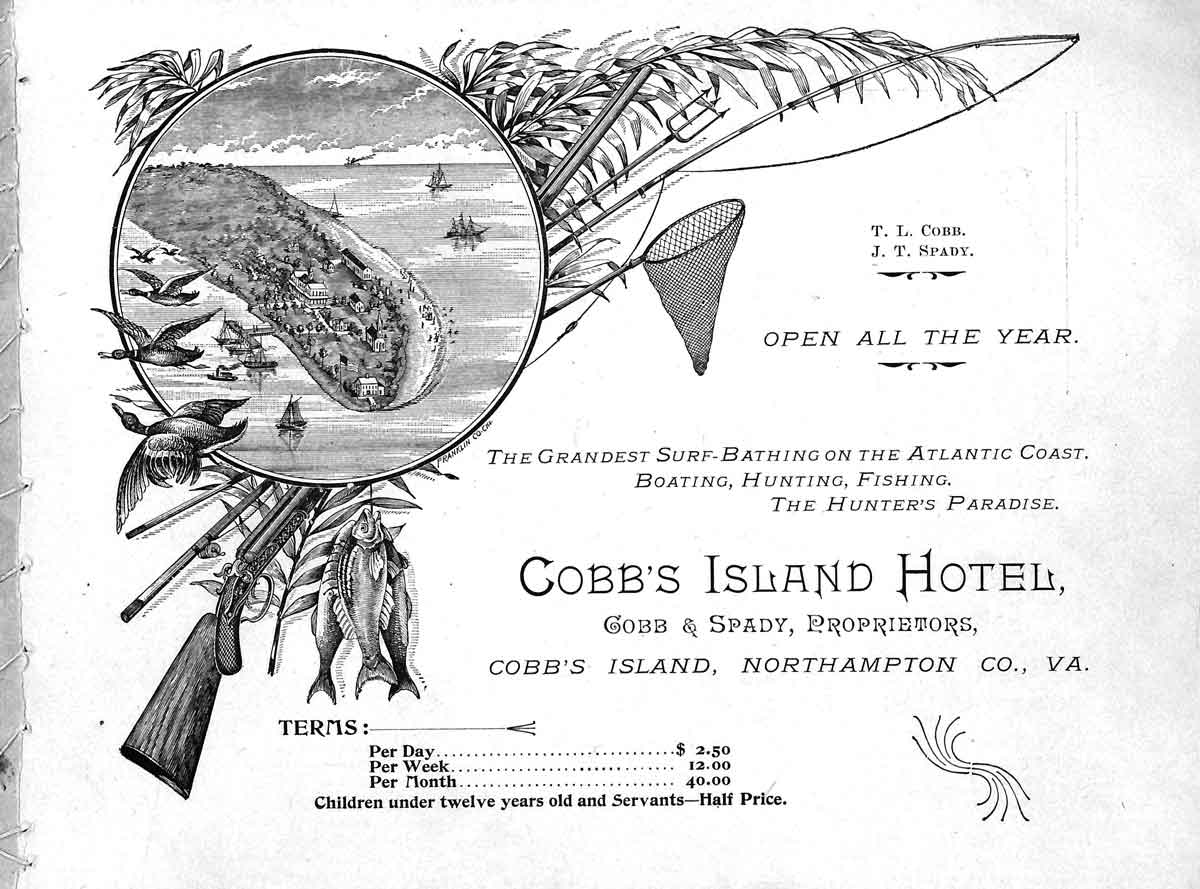

As the word spread and more sportsmen came to Cobb Island, Nathan Sr. knew that he needed to expand his accommodations. Shortly after the Civil War, a coffee barque, the Bar Cricket out of Rio, went aground off Cobb Island. Through hazardous and superhuman efforts, the Cobbs salvaged the ship and received enough money in doing so to build their clubhouse. Named Tammany Hall, it was long and rambling, stretching close to 150 feet. The Cobbs also built a chapel, bowling alley, ballroom, and hired a band. They bought a farm on the mainland to grow fruits and vegetables for their guests and built a mill where meal and grain were prepared.

Many families came for sunbathing and fishing in the summer and fall, but gunning waterfowl and shorebirds remained the dominant sport. For two decades following 1870, the Cobbs operated one of the best-known sporting resorts on the East Coast.

The island’s hotel register, which is housed in the Barrier Island’s Center on the Eastern Shore, shows that between 1874 and 1882 visitors from every Atlantic seaboard state except New Hampshire had stayed at Cobb Island.

The Clara Combs of Cobb Island ferried waterfowlers to the blinds and guests to the island. In tow is a boat filled with dozens of goose decoys made by the Cobbs.

A sailing sloop was purchased by the family to carry guests from the village of Oyster out to the Island. In 1884, a train depot was arranged by the NYP&N Railroad to cater to guests going to the Island. It was named Cobb’s Station. They also purchased a steamer, the NWA Cobb, and used it along with their sailing schooner, the Clara Combs of Cobb Island, to ferry guests back and forth to the resort.

In 1876, a government-issued Life-Saving Station was built on Cobb Island. Three years later it was destroyed by fire, and in 1880 a second, more formidable structure was completed. It was one of 26 built between 1875 and 1881 along the Atlantic coast. The station was manned with full-time crews, including some of the Cobb Island family and guides. A new station was built on the island in 1935, and in 1936 the Life-Saving Stations were officially incorporated under the U.S. Coast Guard. They had been a godsend to many ships, saving many lives. The new Coast Guard Station was decommissioned in 1964 and moved to Oyster on the mainland in 1998. The old 1880 Life-Saving Station still remained on the island, but each storm was slowly taking away another piece of it.

The island had been accreting since Old Man Nathan purchased it in 1839. Through the halcyon days of sport that made Cobb Island famous, only one major hurricane had ravaged the area. It occurred in 1879 and washed away many of the buildings but left the hotel mostly intact. The Cobbs rebuilt and continued with their enterprising business. Sometime after Nathan Sr.’s second wife died, he married Nancy Richardson, and purchased a farm on the mainland south of Oyster.

The Cobb hotels, circa 1885. There were serveral cottages that also housed guests.

By 1890, environmental conditions had changed, causing erosion problems around Cobb Island. The hotel, which was once 500 yards from the beach, was now only 50 yards away. As the island continued to shrink, the die was cast for disaster, and in 1896 it happened. A terrible hurricane struck the Virginia coast, decimating Cobb Island. It washed over the land, taking everything with it but the Life-Saving Station.

After the storm, Nathan Jr. and son Elkanah constructed a smaller clubhouse on the marsh behind the beach, but the glory days of gunning on Cobb Island were over. In 1903, Warren passed away, and two years later Nathan Jr. died. In the late 1920s, Elkanah’s clubhouse burned and he left the island to settle on a farm in Oyster. His cousin, George, Warren’s son, continued to take out hunters for another decade, but the end was near. In 1933, another major storm swept up the Virginia coast. Before the storm hit, the Coast Guard offered to take George off the island, but he refused, primarily because he had nurtured a long grievance with the organization since he and his brother, Arthur, had worked at the station. George’s body was never found.

Left: Elkhanah’s clubhouse in the late 1920s when it was enveloped in flames. Right:The burning clubhouse as seen from a distance.

The devastating storm washed sand over most of the eel-grass flats, killing off this favorite food of the brant, and with the exception of a few scattered flights, they ceased coming. Thus ended nearly a century of the saga of Cobb Island. Alexander Hunter, in his 1908 book The Huntsman in the South, encapsulated it well. “What romancer has ever told of a speck of land in mid-ocean that grew day-by-day, until it became a broad domain, and produced more wealth than any pirate’s hoard ever contained? Furthermore, when this lone isle in the sea passed from the possession of the sons of Neptune, the ocean recalled its gift, the island sank from whence it rose, and now the heaving billows sweep unchecked over the place where but a few years ago there flourished a large village, with its hotel and sportsmen’s lodges.”

The Cobb Hotel falling into the surf after the 1896 storm.

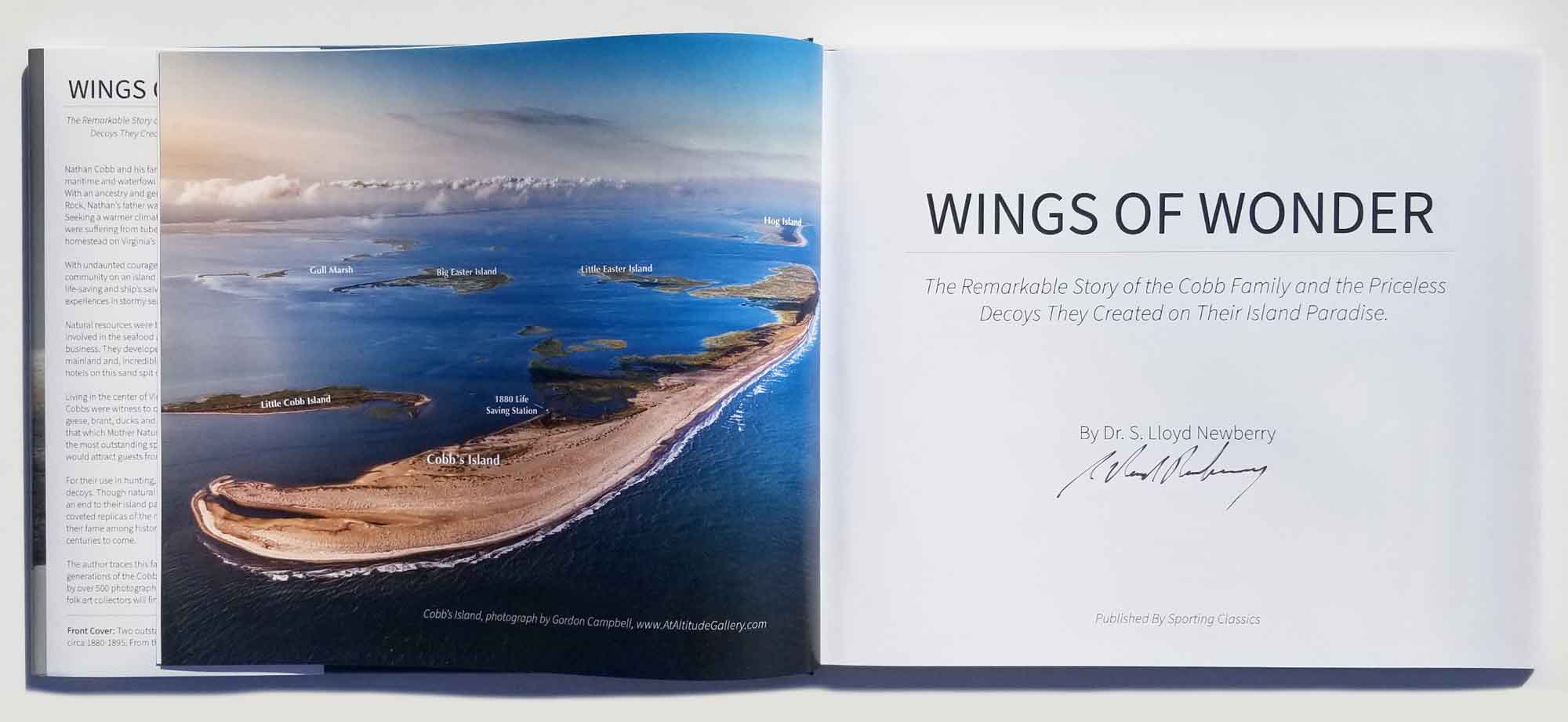

The era of Cobb Island resort is gone forever, but the dynamics of land and water continue to produce change. The sea has once again given back some of the island, and it must now somewhat resemble what Old Man Cobb first witnessed when he walked that beach in 1836.

Now, I was finally on the way to complete my dream of walking on this storied bit of sand in the footsteps of Nathan Cobb. It was about an hour’s run out, stopping several times for Rick to point out the locations of other famous waterfowling clubs. He gave us brief histories of the Barron, Broadwater, and Fowling Point clubs as we paused at the location of each. When we passed through Hog Island Bay, a long string of brant took flight—a living reminder of the past. Though but a remnant of the multitudes of yesteryear, it was heartwarming to see them in those waters.

The author (right) and ecotour guide Rick Kellam visit the remains of the station.

And then we were there. Rick eased the skiff up to the beach on the southern end of the island about 50 yards from the remains of the old 1880 Life-Saving Station. Two of the gables on the roof were still struggling to remain upright, but the chimney had given up in the last storm. The original cedar-shake shingles were still in place on the remaining sections of roof. Amazing to witness, since 1880, and how many raging tempests?

As I stood in the dunes and stared seaward, I was somewhat mesmerized by the howling winds and roaring surf. My thoughts raced back to what this family had created here on this long stretch of beach, dunes, and marsh. Men whose tireless efforts had saved more than three dozen ships and many lives. Men who created one of the finest sporting organizations the country has ever witnessed . . . all gone with the wind and tide. Three generations lived and died here, yet it seems but a moment in time.

But we can go back to experience this great story in several ways. The Nature Conservancy now owns the island, and you can walk the beach as we did. The Barrier Islands Center on the Eastern Shore of Virginia displays many artifacts and documents that present and preserve the Cobb legacy. It’s a must visit. And then there are those wonderful decoys created on the island. They can be found in the collections of private individuals, museums, and on display at public auctions such as Guyette & Deeter and Copley Fine Arts.

Knowing the story of Cobb Island makes just holding one of these decoys a special experience. Click here to learn more about Wings of Wonder, a 327-page coffee table book that details the remarkable story of the Cobb family and features more than 200 decoys created on their island paradise.

Postscript: Fortunately, I was able to find ample information available for piecing together this story. I am indebted to several historians who shared information and photographs. They include: Captain Richard Kellam, Grayson Chesser, Ron Kagawa, Curtis Badger, Tommy O’Connor, the Barrier Islands Center, Guyette and Deeter Auctions, Copley Fine Art Auctions, and Collectible Old Decoys. My thanks also to Bobby Richardson and Henry Fleckenstein.