If I may indulge in the slightest understatement, I’ve been around a while. And I’ve seen a few things. Not as many as some, but more than most. I’ve been lucky enough to have gunned birds all over the world, and there aren’t a great many species that I haven’t hunted at some point or another.

Looking back on all that experience, there are a few things that I just don’t understand. For example, I don’t understand why the dove doesn’t get the respect that it deserves. It truly is the Rodney Dangerfield of gamebirds. Worldwide, there are many variations on the theme, but our common mourning dove is a perfect example of the breed. I haven’t really ticked off anybody in a while, so I’ll just go ahead and say it: The mourning dove really does deserve a place on the list of the world’s great gamebirds.

I can just hear the anguished cries! Surely I don’t mean to imply that the dove is in any way equal to the Easterner’s ruffed grouse? Or the Southerner’s beloved bobwhite quail? How about the Midwesterner’s ringneck? Yep, yep, and yep.

Look at it this way. What qualifies any gamebird to be a great one? In my book, the first criteria—and the most important—is that it’s gotta be tough. Challenging.

Now tell me what’s tougher than doves, taken as they come. Truth be told, any bird can occasionally offer himself as a gift for the righteous, but God knows, the dove does it the least of any bird I know.

Forget the rare, ordinary, run-of-the-mill shot. What about high-flyers riding a stiff wind. Or arriving in clouds to feed after they’ve been spooked by all the commotion, dipping, diving, suddenly climbing, turning, or piling into the stubble at full throttle. They can turn on a dime and cut in the afterburners in nothing flat. And they’ll do it at the least provocation. Or sometimes just for the hell of it. Doves, taken as they come, are as genuinely tough to hit as any bird in existence!

Once, long ago, my father and I were sailing along a South Georgia blacktop highway in his brand-new ’56 Chevy when I happened to notice a mourner flying alongside. He was just taking his time, loafing along, keeping even with us. After a moment I glanced over at the speedometer and was surprised to find that Pop was clocking just a tad over 70 mph. When I looked back, the bird was steadily pulling away from us until he suddenly banked and disappeared across a cornfield. God only knows what one of the little speedsters can do when he’s in a hurry!

Shotshell makers and others who keep up with such things will cheerfully tell you that more ammo is burned for each dove brought to bag than any other bird. They’re so cheerful because they make truckloads of greenbacks every fall on missed doves. Depending on who you’re listening to, the average shell-per-bird expenditure might be somewhere between six and ten. From what I’ve seen over the last 60-odd years of stool-sitting in grainfields, I’m not so sure that even those figures aren’t tainted by an under-reported shell count. I’m unaware of any other gamebird that requires such an expenditure of ammo for each bird brought to bag.

I’ll tell you this, if your honest shells-expended-to-birds-in-the-bag ratio is three to one, you’re a helluva shot. If you can go 50/50 using the same criteria, you’re a true master of the shotgun, and I hereby convey upon you all the reverence you deserve! While I can’t recall the quote verbatim, the redoubtable Gene Hill once voiced his opinion that there had never been a man who could reliably do that in front of witnesses. And he may have been right!

To my mind, the next requirement for any bird to be designated a great gamebird is that it must be a bird of the proletariat. It must be available to the common man. Grouse on the moors are great fun, but to my quaintly American sensibilities, they really can’t qualify for the list of truly great gamebirds simply because they are only available to the very wealthy.

Doves certainly meet that requirement, as well! There are few places in this country—or in the world, for that matter—that don’t have a huntable populations of doves. They’re there if you just look for them. Just ride the roads in late summer or early fall and watch for flying birds or birds on powerlines. Once you find them a few polite phone calls, or perhaps the offer of a token amount of money, will usually result in a place to shoot. If not, just keep looking and try again. You just have to work for them a little bit.

There might be thousands of reasons that people miss doves, but I think that most “true misses” are caused by shooting behind. They’re simply faster than you think, and their tiny size makes it very difficult to estimate range over open ground. Don’t believe it? Try your best to shoot too far in front of a few and see if your average doesn’t improve. Trust me on this: Almost nobody misses by shooting too far in front of doves. And remember that the farther out the bird gets, the more lead is required.

The second most common mistake is shooting too far. This can be caused by poor range estimation, as in, too far—PERIOD. Or they may be shooting too far for their pattern. Good patterns require a good combination of gun and load. Doves, perhaps more than any other gamebird, require premium shells that print tight, even patterns. Cheap promotional shells—the kind used by most dove hunters, tend to throw loose, uneven patterns that don’t reach very far and wound many birds that are feathered, but fly on to die in a distant thicket.

The same can be said for chokes that are too open for conditions. Improved cylinder works fine to about 30 or 35 yards, but beyond that it allows too many birds to “fly through” the pattern and be wounded but not recovered.

The next time you go to a dove field, walk off 35 yards from your stand, and you’ll see what I’m talking about. In most dove fields, more shots are taken at distances beyond 35 yards than at closer ranges.

Closely related is the question of which shot size to use. In my experience, 8s tend to run out of penetration around 35 yards, while 6s tend to run out of pattern at about the same distance. For that reason, I seem to have more consistent results with 71/2 shot in premium-grade shells. I’d even wager a healthy sum that the expensive shells are cheaper than the promos in terms of dollars expended for each bird in the bag. Actually, I think I’ll try to quantify that for the doubters and write it up in a future column.

Nash Buckingham was a hero of mine during my formative years. He was a true gentleman of the “Old South” and most likely the most famous bird hunting writer of his time. He was also a superior shot. Suffice it to say that he had ample experience hunting birds of all kinds. If Nash Buckingham didn’t know what he was talking about, then nobody ever has.

In January 1947, when I was still in diapers, Nash published a story titled “The Dove.” In that piece, he described the dove as our “premier wing target.

“From the standpoint of change of pace, aerial gyrations—and especially at high speeds—sheer ability to absorb a lethal punch but keep going, no other American gamebird for its size can compare to the dove.” He added, “The top-flight dove shot need not fear to face any internationally gunned species a-wing.”

I wholeheartedly agree with Nash, a man whose experience surely exceeds my own by a huge margin. I’ll also agree with Nash’s British friend, who was an accomplished game shot facing our mourning doves for the first time. He was expected to give the “good old boys” a tutorial on wingshooting, but upon returning to fetch more shells after his first encounter, he sheepishly reflected on the experience.

“They are very, very small, dear boy, and fly very, very fahst.” To which I can only add, “Amen!” Lets give the dove a little respect. He’s a genuinely tough customer, and an outstanding gamebird.

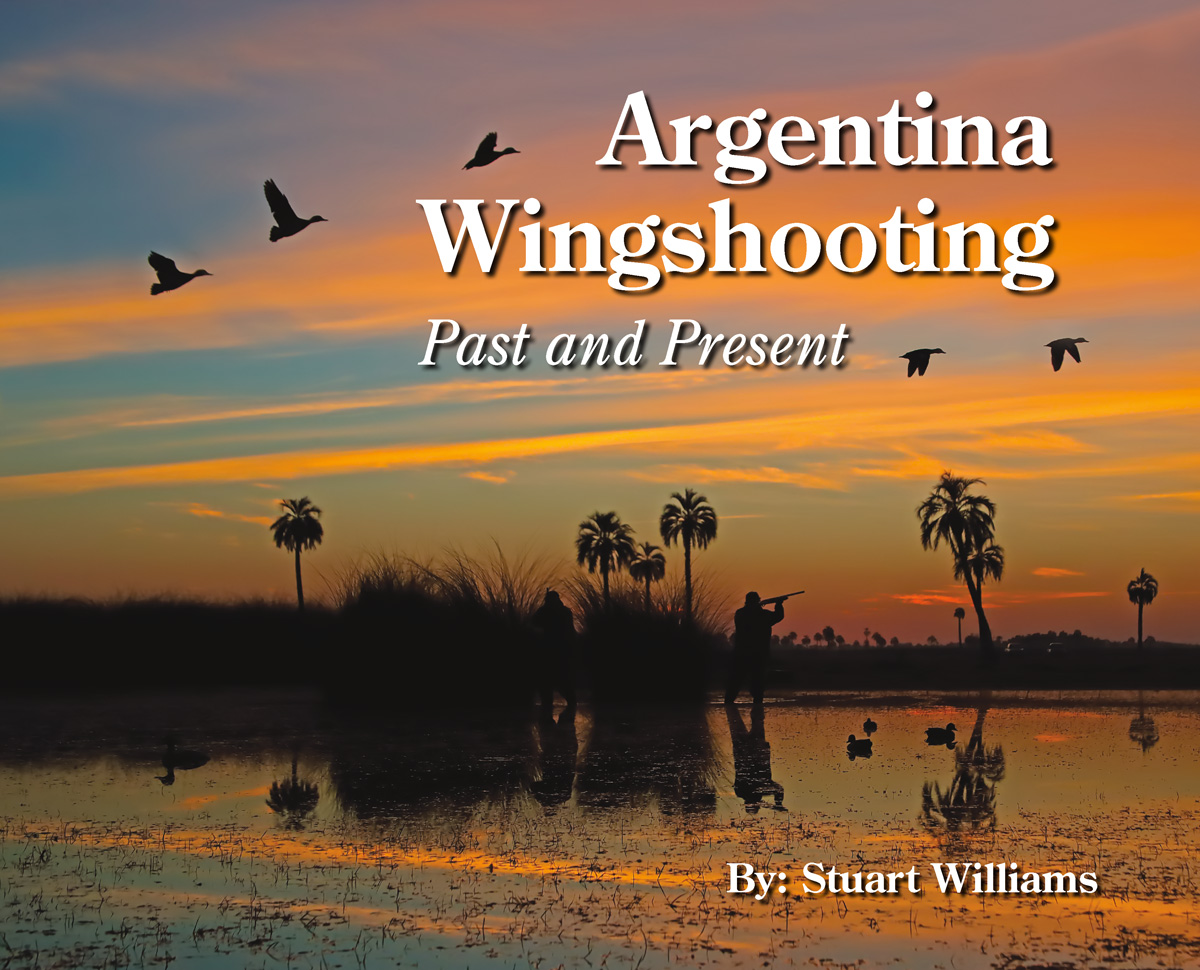

Argentina Wingshooting: Past and Present

Argentina Wingshooting: Past and Present

Click Here to Learn More

On these 256 pages, you’ll join Stuart on his most spectacular shoots where clouds of doves darken the sky and where seemingly endless flocks of ducks and geese stream down from the heavens.