July 14th, 4:16 a.m.

Dear Tom,

When I first laid eyes on the old rifle back in the fall of ’54 it was already pretty used up, at least on the outside. On the inside it was still in good working order.

I guess Dad figured it was high time for his boy to fire a gun for real. After all, I was three months past my fourth birthday and had been tagging along with him and his red-checked wool coat ever since squirrel season opened back in September. But all he owned was that big 12-gauge over/under shotgun and his 35-caliber deer rifle, so he’d borrowed this old .22 to remedy the situation.

It was actually Uncle Claude Reedy’s rifle—an eight-shot bolt-action Marlin Model 80-DL. I have no earthly idea how Uncle Claude came to own it, but if I had to speculate, I’d bet you a dollar that he didn’t buy it new. Instead, he most likely acquired it in some sort of trade—possibly swapping one of his home-cured country hams for it, or maybe even a couple of Aunt Eva’s prized guinea hens.

Uncle Claude and Aunt Eva lived near Wytheville, and sometimes on Sunday we’d load Granny Altizer up in Dad’s old two-tone Mercury and make the twisting three-hour trek from Bishop across Stoney Ridge, through Tazewell and Thompson Valley and then up and over One Way Mountain to see them.

Uncle Claude was Granny’s lone brother and, as I said, his old .22 was the first gun I ever shot. When he died, Aunt Eva gave it to Dad, and when I turned 10, Dad trusted me enough to let me hunt with it on my own. By the time I left home eight years later, I had taken a couple million squirrels, a few thousand rabbits, a dozen or so grizzlies, four tigers, two elephants, one troll and a Studebaker with the old rifle, and it was still working fine.

Enter my two little brothers.

When I graduated from high school and hit the road, your Uncle Alan had just turned nine and your own father wasn’t yet three years old. But they both loved the same things Dad and I loved, and that old Marlin was one of them.

And so as my own love interests expanded from things that went bark and bang to include cars and girls and Kodachrome and reading well-written stories and books, Uncle Claude’s old rifle fell first into your Uncle Alan’s hands and later into your dad’s.

But somewhere along the way its rear sight got busted off, and your Uncle Alan took a tumble down the side of a 10-foot rock face and broke the stock at the grip. He took the old gun apart and tried to repair the damage, but the wood was hopelessly splintered. Eventually he stashed the barreled action in the back corner of Mom’s hall closet where it languished for decades until I finally happened across it.

“What in the world is this?” I asked, to no one in particular.

“What’s what?” Mom replied, as I drew it from the darkness and showed it to her.

“Oh—that’s what’s left of that old gun Alan broke years ago.”

And as I gazed at what was left of my darlin’ companion from the ’50s and ’60s, I asked, “Would you mind if I took it home and tried to fix it?”

“I wish you would,” she replied adamantly. “That thing’s been taking up space in my closet for years.”

My first call was to Herb Riley, a master gunsmith of magical powers and illustrious repute who lived less than an hour away. I explained what I had and what was missing, and the next day I took the old barreled action to him.

“Overall, it’s in reasonably salvageable shape,” he assured me, once he’d examined it. “The problem is going to be finding a stock.”

Please understand, this was back in the days before the internet, and a thorough search for something as scarce as an obscure, half-century-old rifle stock was going to be a serious challenge. Four months went by without success, but finally Herb called to say he had a possible solution. He’d found an ancient, beat up Remington stock that, with a few modifications, just might be made to work with the old Marlin.

Now we’re in business, I thought, as Herb began looking for some bottom metal and a replacement rear sight and trigger guard. In a couple of weeks he had parts in hand and started fitting everything together.

But just as time catches up with aging guns, it also catches up with aging gunsmiths, and Herb’s health took a turn for the worse and we never got the old rifle finished. There were still some problems with the extractor far beyond my ability to address, and I set the gun aside for a few weeks and a few months and then a few years, built a business, wrote a few books and stories of my own, and only recently turned my attention back to Uncle Claude Reedy’s rifle.

But where to begin?

Or perhaps more accurately, where to continue?

The restored Marlin Model 80-DL.

I mentioned the gun to my friend Jim Carmichel as we were having lunch with the posse one warm Thursday afternoon, and he and I wound up back at his house with him doing a computer search for various missing pieces and parts and, dare I hope, for a proper Marlin stock. Having been the world’s preeminent rifleman for the better part of six decades, Jim was able to source everything we needed—including that elusive original Marlin stock, albeit in pretty rough condition. Within a couple of weeks all the pieces had arrived and we were off and running.

The first thing we did was make sure the barreled action fit the stock—which to our delight it did. I removed the broken rear sight and gently tapped a new one into place and attached the bottom metal plate and trigger guard.

Everything fit, so I checked the bore and cleaned it thoroughly, took the old gun out behind the house and fired a single shot into the side of a cardboard box. And though the spent brass failed to eject properly and the safety needed attention, I came within a couple of inches of the small black circle I’d scrawled into the center of the box and knew I had something solid to work with.

So now I turned my attention to refinishing the stock.

To say it was in bad shape or good would be only half right on either account. For while it fit the barreled action and had no major gouges or structural flaws, the finish was in abominable condition, with the original varnish blackened and bubbled and rough as a cob. I took it to my friend and expert stock maker Monte Fleenor to get his opinion, and he said it had probably either been through a fire or had been stored in some intolerably hot attic for too many summers. Whatever had happened, it would require a serious stripping agent, and he sent me away with a home-brewed potion that he assured me would melt the stripes off a zebra and said not to spill it on anything vital.

I tested a small area along the grip before diving in whole hog. After a half hour, the burnt finish began to go all gooey and I started carefully scraping away the excess with a flat metal blade. It seemed to work, and for the next three days I continued to refine the old stock until I had it down to bare wood. The excessive heat that had boiled and blackened the original varnish had also hardened the wood itself, and I considered this a good thing as I shaped and sanded it to my own tastes until everything felt just right.

I put all the parts back together and made a couple more minor adjustments, then took the gun apart one last time, gave the bare wood a final touchup with 600-grit wet-dry sandpaper and was ready to start applying the finish.

For the next few weeks I alternately stained and oiled and sanded that old stock, letting it relax and cure between treatments until I was satisfied. I put everything back together very carefully and took my newly restored old companion first to Jim and then to Monte to show them the results. True to form, Monte began dinking around with that problem ejector, and in less than an hour he had it working just fine.

And so, Tom, though I still have some detail work left to do, that’s the story of Uncle Claude Reedy’s old Marlin, at least up until now.

But tonight I’m passing the gun down to you.

Your dad and Uncle Alan and I will explain it to you, and when you turn four we’ll take you out and let you shoot it for yourself, just like your grandfather did with me a lifetime ago.

Take care of it, little man, and treasure it—then someday hand it along to the next generation.

Above all, be safe!

For even though you and I have yet to actually lay eyes on one another, please know that I love you more than I can ever express. And that I take great comfort in knowing that although you’re still only three hours old, at least you now have a rifle of your own.

Peace. —Uncle Mike

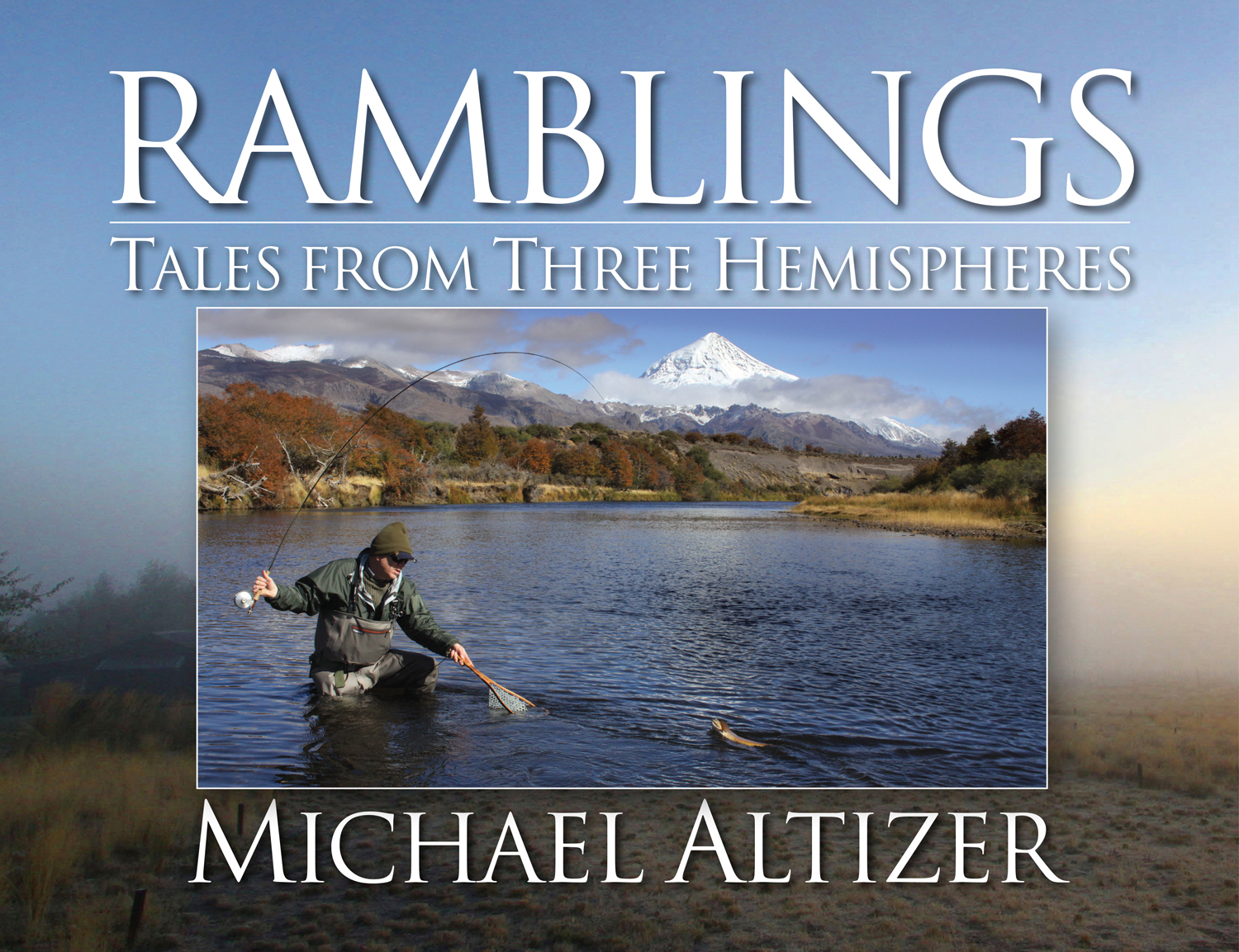

Ramblings: Tales From Three Hemispheres

Click Here to Buy Now

The author always welcomes and appreciates your comments, questions, critiques, and input. Please keep in touch at Mike@AltizerJournal.com.