There are times, my friends,” the parson gravely relighted his pipe, “when the truth must be used with moderation.”

I often wondered how the parson stood the society of two such shop-worn angels as Rick and Wes. The rough-and-ready ways of this unrivaled pair must have taxed his Christian forbearance, as their tales sometimes taxed his credulity. There was the night, for instance, I spent with them on the Little Pee Dee.

“The smartest thing I ever saw,” Rick stretched his long legs before the hickory fire and began, “was an old buck deer we used to hunt on the Savannah River. That buck would jump a five-foot fence just to get himself chased now and then. Just for the fun of the thing.”

“You mean,” put in Wes, the skeptic, “to set there and tell me…”

“I mean to set here and tell you that old son-of-a-gun naturally enjoyed it. He holed up on Take Notice Jones’ place where he knew he was safe, because old man Jones had the place fenced on the swamp side and kept outriders to drive hunters off. Well, whenever we’d turn the dogs loose in the swamp that buck would sail over the fence, give them dogs a little settin’-up exercise, and then sail back and go on about his business as calm as a cucumber.”

“What do you think of that one, parson?” challenged Wes. “A little strong, wouldn’t you say?”

“My profession,” replied the parson judicially, “has taught me to be reluctant about impeaching the statement of another.”

“You see, Rick? He’s callin’ you one, plain as day.”

“No,” corrected the parson gently. “I had never heard of a deer that smart, it is true. Must have been a remarkable old buck, I’d say, but in a state as fine and big as South Carolina you’d expect to find an outstandin’ deer here and there.”

“Well,” Wes was not to be outdone, “the smartest thing I ever saw was a wild turkey. An old gobbler that could read.”

“You mean to set there and tell me…” bristled Rick.

“I mean to set here and tell you that gobbler could read,” continued Wes unruffled. “And we’ll let the parson be the judge. A tremendous old gobbler he was, with an eight-inch beard and as smart as a steel trap. Stayed in the Four Hole swamp and always kept a big flock with him. But whenever we’d take our turkey dogs in there and flush the gang so we could yelp ’em to our blinds, you know what that bearded old gent would do? Well, I’ll tell you. He’d fly across the border and light up in a big dead pine, just above a big sign that read ‘GAME REFUGE: NO TRESPASSIN’.’ Then, like a preacher in a pulpit, he’d call out every blessed turkey in that part of the swamp. Now, parson, didn’t my turkey have more sense than Rick’s deer?”

“I’m not an authority on turkeys, but I’d say offhand that was a remarkable old gobbler, a very remarkable one, in fact. But in a sovereign state like South Carolina, chances are there would be an outstandin’ gobbler here and there,” the parson wisely evaded.

“If you want my opinion…” interjected Rick with virtuous warmth.

“Now, boys,” the parson lifted his hand in a pacificatory gesture, “when it comes to deciding between such intellectual giants as Rick’s buck and Wes’s gobbler, I hate to sit in judgment. Who am I to pass on a sportive old buck’s idea of self-enjoyment, or to impugn the capabilities of an embattled gobbler when the welfare of his followers is at stake? Animals are sometimes not so smart as we think they are, and perhaps sometimes much smarter. We all know that they often bluff one another, for instance, and I wonder whether they don’t bluff us, too, more than we suspect. I knew a dog, for example, that completely bluffed its owner and came within a gnat’s nose, to use one of Rick’s locutions, of bluffing me.”

“July hound, wasn’t it?” Wes sat up. “I had one once…”

“No. Bird dog. An Irish setter, in fact.”

“Let’s have the story,” encouraged Rick.

“Sure. Your turn anyway,” seconded Wes.

“I’d rather not recall the incident,” the parson demurred. “In a way, it brings up unpleasant memories. Fact is, gentlemen, that old bluffer caused me to deviate from the high regard for truth which wearers of my cloth are supposed to exemplify, and perhaps the story had better remain untold.”

“You mean a dog made you tell a lie?” hopefully asked Wes.

“Wes, you are such a literalist!” chided the parson. “I said he caused me to deviate. In other words, to fall into a voluntary verbal inexactitude.”

“A voluntary verbal inexactitude,” repeated Rick, smacking his lips over the edifying phrase. “If that ain’t a masterpiece. The next time anybody calls me a liar…”

“Oh, dry up, Rick, and let the parson tell his story.”

“Since I am among friends,” agreed the parson, “and since both principals concerned are now dead, I see no reason for withholding it. Throw a log on the fire, Wes, and I’ll try to reconstruct my experience.

“It was some twenty years ago, I should say. I was then a young preacher on my first charge up in Virginia, and somewhat more interested, I am afraid, in bird hunting than in the spiritual wellbeing of my small congregation. I accounted myself lucky, therefore, when I received a hunting invitation from an old Judge Bagby, who had been a great crony and shooting companion of my father’s in their younger days.

“The judge lived in a historic and half-forgotten old county, as famed for its fine hunting as the judge for his fine dogs. So, as you can imagine, I lost little time in crating up my two young setters and heading for the old homestead. On reaching the county, I engaged an affable young fellow, whom I had chanced to meet, to conduct me over the meandering red roads that led back to the judge’s hereditary seat.

“My guide, who knew my host well, proved chatty and informative. I learned among other things that the judge, who was of a distinguished Virginia family, was held in great affection throughout the country, and that in spite of his advancing years he was as ardent a sportsman and lover of fine dogs as ever. Indeed, that he now owned a particularly fine hunter for whom a rich Northerner had offered him a thousand dollars, and that it had looked for a time that the judge would have to sell the dog to prevent foreclosure on his homestead. But, my guide further informed, the judge had instead hit upon the happy expedient of selling his ancestors.”

“Did you say selling his ancestors, parson?” Rick asked.

“Yes, not so complicated as it sounds, perhaps. The judge was of distinguished lineage but impoverished. That is, he had a family but no money. A newly elected congressman had money but no family, so the judge sold the fellow his family portraits. The fellow took them to Washington and hung them up in his own fine house, and the judge extinguished the mortgage.”

“That ain’t so strange,” offered Wes. “I got two half-uncles I’d swap for a middlin’-good coon dog any day, and they ain’t hung up yet, either.”

“Before you can sell ancestors,” observed Rick not impersonally, “you got to have some there’s a market for.”

“Anyway,” resumed the parson, used to such unflattering exchanges between the two, “I was mightily pleased with the prospect of hunting with a dog held in such esteem by so discerning a judge. When I arrived the old gentleman welcomed me with great heartiness, but when he noticed my setters he was momentarily taken back.

“‘Young man, I neglected to write that you needn’t bring any dogs. Didn’t you know, sir, that I still have the Senator? Since you’ve brought yours along it would be a shame not to hunt them, but you must not judge them by tomorrow’s hunt. They will be competing with the Senator, you know,’ the judge said, with simple sufficiency.

“As if in answer to his name, there strode forward a great red dog. He was magnificently coated, with a splendid sweep of tail and a majestic head—altogether the handsomest figure of a dog I ever saw.

“That night the talk ran strongly to dogs in general and the Senator in particular. From an old trunk the judge brought out a pile of yellowing papers, and with these as a text gave me such a masterful disquisition on the Senator’s family tree that I reflected rather shakily upon my own. You know what a genius those elder Virginians have for tracing kinship, what with first cousin second-removed and such intricacies. And all that time the big dog stretched gravely before the fire as if such laudatory proceedings were to be taken for granted.

“‘What I want you especially to notice tomorrow, which will be the only hunt I’ve taken this year, is the Senator’s great nose. It’s nose that makes a dog, you know. I’ve bred for that, and I’ve got it,’ he concluded proudly.

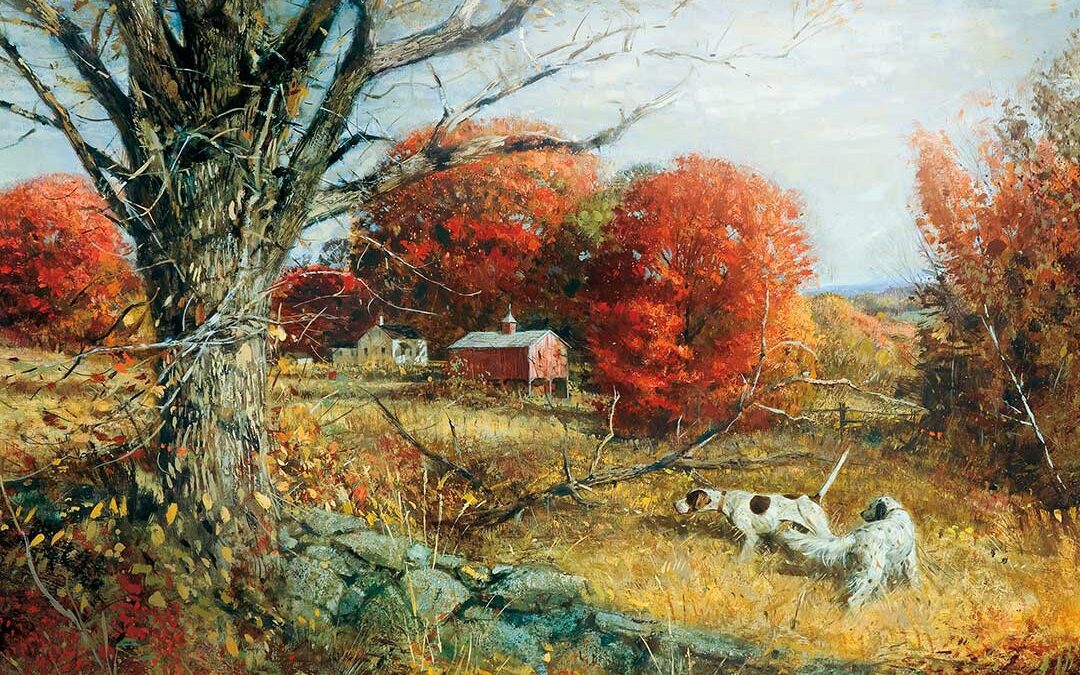

“As soon as the sun melted the frost the next morning we took the field. It was a beautiful place. The farm lay in a great bend of the river, its wide fields rolling away to the lazy James that glinted in the distance. And were there birds in those overgrown fields! Within fifteen minutes we topped a slight rise to find all three dogs dead on a covey. At the apex of the triangle stood a great red statue with head and tail proudly aloft, a picture that an artist might have traveled far to see.

“Remarking that coveys were plentiful, the judge suggested that we forego the singles. And, indeed, before another thirty minutes had passed we crossed a hedgerow to find all three dogs piled up again, with the Senator dead on and my dogs backing close behind as before. ‘Here,’ I said, ‘is such a dog as a man is seldom privileged to hunt,’ and when within the hour the identical performance was repeated, I began to wonder whether the judge wasn’t right: that my dogs or anybody else’s were useless when the Senator took the field.

“My dogs were good—I’ve never had better to this day—but here was an old master who had beaten them three times in a row. The technique of a dog that could do that was worth watching. I stepped up on a stump to watch proceedings in the rank ragweed ahead. In a moment I observed something that made me a little curious. All three dogs were hunting actively enough, but the Senator was continually hunting behind mine. And when one of mine tested the air and pointed, the big Irishman, to my increasing puzzlement, glanced guardedly about, then sneaked forward and boldly planted himself just ahead of my dogs. The thieving old reprobate! Had he been doing that all along? Well, I would find out definitely.

“Thereafter I walked ahead so I wouldn’t miss too many tricks. My enterprise was soon rewarded. When my dogs began to make game the big red dropped cautiously behind them, fussing around busily and making a great pretense of hunting, but carefully avoiding any territory not already covered. Apparently he was afraid to find birds.

“When my dogs located the covey he again glanced covertly around, slunk guiltily ahead, and imperiously planted himself. That tragi-comedy kept up a better part of the day. Each time the judge walked up proudly and magnanimously reassured me that my dogs could not be judged fairly in such competition, that they would doubtless show up well under other circumstances. And every time this scene was reenacted my blood pressure climbed higher and higher.

“There was another thing, too, that struck me as peculiar. Instead of picking out his birds, the judge invariably shot into the coveys, sometimes missing altogether. This, coupled with his unwillingness to follow the singles, puzzled me no little, since the judge had the reputation of being a crack wingshot. Watching him narrowly, I finally divined the truth: his eyes were so bad he couldn’t follow the singles, yet throughout the day he stoutly refused to allude to his shooting or to offer his impaired vision as an alibi. Matter of fact, I doubt whether he could distinguish one dog from another at any distance.

“When birds fell, which was most often to my own gun, the possessive way in which he ordered the Senator to retrieve somehow conveyed the idea that he was trying to protect his secret of failing vision from the dog as well.

“But it was the conduct of the dog that puzzled me most. About him I had a suspicion as wide as a barn door, but one I couldn’t confirm unless I should have an opportunity of hunting him alone. Late in the afternoon I contrived such an opportunity. As we reached the river and turned back, the judge considered a moment which route to follow, remarking that the two hunts were equally good. I promptly suggested that we separate so I could have the pleasure of hunting the Senator alone. He assented at once, but the dog hung reluctantly back, an act so out of character as to call forth the wondering comment of the judge. Only after peremptory orders from his master did he consent to go at all.

“Alone with me, the Senator was in a quandary, and his every manner showed it. The old fellow made a few halfhearted excursions from the path, sniffed importantly, then fell back as if he expected to get by with it. When I forced him into the field there was an embarrassed uncertainty in every movement. Presently, to his deep mortification, he walked smack into a feeding covey. He had not smelled them at all. During the rest of the afternoon he blundered into two other coveys and any number of singles. Then, as if recognizing the uselessness of further pretense, he quit cold and refused to budge from the path. Now that the judge was not along to witness his infamy the masquerade was abandoned.

“The Senator had lost his nose, as I had suspected. Lost it completely, either from the encroachment of age or some bodily illness such as the attack of pneumonia he had survived that winter. As you know, an impairment of the sense of smell often accompanies age. All the morning he had been bluffing high-handedly. I sat down and called him to me.

“‘Senator,’ I said, ‘you are nothing but a hypocritical old scalawag. My dogs have found every bird while you piously appropriated every point they made, put them in a false light, and had the judge sympathizing with me. I am going to expose you as soon as I get back. I am going to denounce you to the judge as the swindler and grand rascal you are, sir!’

“The more I thought about it, the madder I got. I was a younger man, then,” the parson put in parenthetically, “and I could hardly wait to unmask the old fraud and vindicate my own dogs. When I arrived I found that the judge had preceded me and that supper was waiting.

“Across the table the old gentleman beamed pridefully at me.

“‘Well, how did you and the Senator get along?’ he asked.

“‘There is something I must tell you about that dog, sir. The Senator is nothing but a—’

“I was aware of a movement under the table, of the pressure of a big muzzle against my knee, and of a warm tongue caressing the hand in my lap. I glanced indecisively at the telltale little rectangles on the wall where the portraits had hung, then I resolutely finished:

“‘The Senator, sir, is nothing but a genius!’

“And I left the two old frauds to bluff each other a while longer. There are times, my friends,” the parson gravely relighted his pipe, “when the truth must be used with moderation.”

First published in the April 1939 issue of Hunting & Fishing magazine, and then in Tales of Quails ’n Such in 1951.