After my good luck with ibex I thought the Armenian sheep would be a snap…but I figured wrong.

The oil-producing nations of the Middle East are usually thought of as scorched stretches of shifting sands where the midday sun broils your brain and sizzles skin like spit on a hot griddle.

In truth, though, as my hunting pal Fred Huntington and I found out, Tehran, the capitol city of Iran, is on about the same latitude as Nashville, Tennessee, and come winter the noontime sun is liable to shine on a foot of snow. On the day Fred and I arrived in Tehran, in the first week of January 1974, it began to snow. Four days later, when we were scheduled to fly out to sheep country, the snow was still coming down, and therein lies a tale within a tale.

Iran Safaris, Lt. had booked us on a quick jet flight to Tabriz, a good-sized city in the northwestern panhandle of Iran, not far from the Turkish and Russian borders. There we were to meet our guides and drive into the rugged mountains of the Iranian-Russian frontier where we would hunt ibex and the sporty little Armenian sheep.

Unfortunately, four days of heavy snow proved too much for Mehrabad airport, and our plane was grounded until the following day. This was no real problem because we had a bit of extra time anyway, and besides, I’d grown rather fond of watching the traffic of Tehran perform in the snow. In the best of weather the average Iranian driver is an unguided missile who apparently never attempts a left-hand turn except from the outside right lane. When the streets get a little icy, it’s a downtown demolition derby with two million contestants and lots of fun to watch—from a distance.

Our flight the following morning was again canceled, and with the snow still coming down, we thought it wise to forget the airplane and try a train. Which is why the afternoon found us not only comfortably encased in the brocaded and varnished mahogany elegance (if somewhat worn) of a 1914 French railway coach, but also sharing our tiny first-class compartment with two very apprehensive young ladies. One was a mod-dressed gal who identified herself as a nurse and spoke just enough English to let us know that she wasn’t at all keen on spending 18 hours boxed in with two American men. The other was dressed in the centuries-old fashion of full-length robes and the face-hiding veil of traditional Moslem womanhood. All we ever saw of her were flashing black eyes and hints of a lithe form under layers of exotic garments.

“Fred, do you think we ought to tell our wives about this?”

“I don’t know about yours, but mine’s not going to believe me anyway. What worries me even more is what we’re supposed to do when it’s bedtime.”

“I wish you hadn’t said that. Now I’m worrying, too.”

Late in the evening the worst of our worries came true when a porter came by and converted our seats into four beds, two above and two below. The women claimed the upper and lower on one side, and there was no curtain between. So with nothing left to sit on, it was all too clear that we would all have to hit the sack.

With a chorus of nervous (I suppose) giggling, the two ladies scrambled between the sheets. Fred, who can sleep anywhere, promptly claimed the lower berth on our side of the dimly lighted cubicle and was soon snoring like a hippo in heat.

This was all too much for my modest soul, so I slipped out the door and spent much of the night on the freezing-cold observation platform in the company of a turbaned Mullah (I think that’s what he was.) who apparently didn’t appreciate my company and expressed his displeasure with lots of shouting and hand-waving in my face. In addition to whatever it was about me that he found so aggravating, he also suffered from weak kidneys because periodically he would rush into the nearby restroom (a hole in the floor), only to return and continue his remonstrations.

The train never exceeded 20 miles per hour and stopped every 15 minutes, and thus did two American hunters chug across snow-swept Asian plains that in centuries past had been crossed by Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, and the Abyssinian hordes.

Just after dawn we arrived in Tabriz and met our two guides, Manouchehr Abdollohian and Hooshang Bakhtiar. After a brief but verbal Iranian-style baggage hassle, we were on our way north toward the Russian border. Our home for the next week was to be only a dozen miles or so from what was then the USSR.

Our hunt was arranged to include ibex, a goat-like creature with high, sweeping horns, and three varieties of Iranian sheep: the red, urial, and Armenian. The urial sheep is probably the best known and most popular of the Iranian sheep, at least among American hunters, because the curl of its horns is fairly similar to that of North American wild sheep. The Armenian sheep, on the other hand, is probably the least known and, in fact, has been taken by relatively few American hunters. Among the very smallest of the world’s wild sheep, the Armenian stands no more than three feet at the shoulder and sports horns that curve back over the neck and shoulders, as opposed to curving around the jaw like the horns of North American sheep.

Armenian sheep range over parts of Turkey, the northern mountains of Iran, and the southern tip of Russia eastward from the Caspian Sea. They roam in herds numbering from only a few members up to several dozen, and as the seasons change they wander over a large area, seeking the high country during the summer and dropping to lower elevations during the cold months. When they come down to the lower pastures, they come in contact with domestic sheep and shepherds often enough to become extremely spooky. This wildness, plus their small size, makes them a challenging trophy to stalk and shoot.

Our game plan for the first day was for Fred, guided by Manouchehr, whom we quickly nicknamed Manny, to go after the little sheep while Hooshang and I went into the high country for ibex.

After a lung-busting climb and a cliff-hanging stalk (literally), I took a fine ibex ram. Fred and his porter located a herd of sheep, but unfortunately, found out firsthand how wild and hard to hit they can be.

According to Fred’s account that night, a herd of the little sheep had spooked at the sound of someone’s coat brushing against a boulder some 200 yards away. Later in the day they had gotten reasonably close to another ram, but Fred overestimated the range and shot a little too high. The small size of the Armenian tends to make them look farther away than they actually are, a hint I made a point to remember.

After my good luck with ibex I thought the sheep would be a snap, but I figured wrong because the herd we finally spotted wasn’t down low at all, but high up on the snow-covered face of a steep mountain. A three-hour climb got us to within about 500 yards of the herd, but beyond that we were stymied. There were no trees, boulders, or gullies to hide behind, nothing but a steeply slanting expanse of landscape covered by a foot of snow.

The herd was bedded down when we first spotted them, but as we came closer, they stood up and began nervously milling about. Clearly, there was no way we could get closer without spooking them all the way to Russia, so my only choice was to try a long shot. At that distance I needed a solid rest, or at least to shoot from the prone position, but there wasn’t anything around that could be used for a rest.

After I had floundered around in the snow for a moment, trying to get some sort of steady position, it became clear that the only way I would get anything near a solid rest would be to support my rifle over the supine torso of Hooshang or one of the others. But asking someone to plop down and stick his face in the snow while you use his back for a shooting bench takes a bit of diplomacy, and I wasn’t all that confident I could persuade anyone to do it.

Hooshang, though, must have been reading my thoughts.

“Jeem,” he said, “I have a plan. I will get down into the snow and you can fire your rifle over me.”

“Now why didn’t I think of that?” was my answer. “Okay, but put your fingers in your ears. I’ll be very careful.”

“Ah, Jeem,” he smiled back with charm and a soft pat on my shoulder, “it is a pleasure and honor to be of service to so great a hunter.”

“Oh oh,” I said to myself, “the price of tips to guides just went out of sight.”

A few moments later Hooshang had wriggled himself face down into a fairly stable position, and I was aiming my .280 rifle across his back, trying to time my trigger pull to the up and down of his breathing.

It was a pretty hopeless shot, I guess, and by the time the echo of report stopped bouncing from mountain to mountain, the sheep, including the one I’d shot at, were long gone.

Besides Hooshang and me, our party included the local game guard, a young fellow who carried our lunches and tea-making gear, and a grizzled old sport who helped me with my rifle and cameras. They all had seen me shoot, and the unanimous option was that I’d missed the sheep.

Yet something was puzzling me, and I told Hooshang to ask them if anyone saw the bullet kick up a puff of snow.

After a flurry of conversation in Iranian and Turkish, the report was in: “No one saw where your bullet hit. It was a very long shot and too far to see.”

“Then tell them I want to go up to where the sheep were and see where my bullet hit.”

“But Jeem,” he stammered, bewildered at my crazy notion, “the sheep is gone, we must go to another mountain to find other rams.”

“We’ll do that later,” I insisted. “When I miss, I want to know why and how far.”

The truth was that I had a pretty good feeling that my bullet had not missed, but I didn’t want to insult them by saying that I thought they were mistaken. At the same time I didn’t want to sound too boastful either.

“If it is your desire, we will find the place where your bullet made a hole in the snow.”

“You are most kind,” I answered. “That will make me very happy.”

The others just stared in amazement at the crazy American who would climb a mountain to see a hole in the snow.

When we climbed to where the sheep had been, they were treated to an even greater dose of amazement. Near where the ram had stood, like sprinkles of rose petals, was a crimson-splotched trail leading around the mountain.

“Jeem, Jeem, I do not believe what I see,” whooped Hooshang. “I have never seen such a shot.”

“Just luck,” I replied, trying to sound modest but feeling smug and wholly satisfied at having insisted on a closer look.

My self-satisfaction was short-lived, however, because it soon became apparent that the ram wasn’t badly hurt after all. After some three hours of hard trailing through knee-deep snow, we got only one final look at him. He was running along the rocky side of an almost vertical mountain face, and except for a somewhat stiff rear leg looked to be in good health. Somewhere in the mountains of northern Iran I believe there still lives a very fine, but extra wary, Armenian ram that walks with a slight limp.

By Iranian hunting rules, a hit is the same as a kill, and you pay the full price. This is the reason the game guards accompany hunters, not just to see that no one cheats, as I was happy to learn, but also to assist the guide and make every effort to find wounded animals so the hunter can claim his trophy. Though I’d now lost one sheep, my license was for two Armenian rams and time-wise, thanks to my first-day luck on ibex, I was still ahead of the game.

The next day we headed west along a river that snaked through a broad, red-soiled valley. Mostly, the land was used for grazing, but here and there one could see where a cotton crop has been coaxed out of the rocky ground. Once, generations ago, there were trees, but they were used up and never replaced. Now the landscape was so barren that a tree is a treasure and dried sheep manure fuels even the stoves used for cooking as well as heating homes. Actually, the land looks very much like certain areas of the American West—washed and gullied with tough grass and cactus growing through pavement-hard ground of basalt gravel.

Hooshang had the foresight to rent a couple of scrawny horses that proved especially useful when we came to the river. Fed by melting snow in the mountains, the river was about 150 yards wide, belly-deep to a horse, and treacherously swift. It was all our horses could do to fight the current, and at any instant I expected to be swept away by the icy torrent. The nags were tougher than they looked, though, and we made several crossings without so much as a wet sock.

Toward mid-afternoon we topped a low range of hills and descended toward a mud-walled village. So far as I could see there were no roads leading to the village, no motor vehicles, and no electric lines. Nothing at all, in fact, to suggest that the date was 1974, or 200 or even 500 years earlier.

As we came closer we were met by a trio of horsemen who turned out to be an official welcoming party. One of the three was the mayor, or at least so I judged by his official air and pinstripe suit, who displayed his wealth and position in the form of several gold teeth. He bid me welcome in the formal way by bowing stiffly while patting his chest with his hand. This gesture means, “I make myself humble before you,” and when I returned the centuries-old salutation, he beamed in 24-karat delight and surprise.

The local lingo turned out to be a Turkish dialect not understood by Hooshang, so for a while we only stood around, politely grinning at each other. His Honor, I noticed, kept eyeing my rifle, so I unloaded the magazine and handed it to him for a closer look. He was especially fascinated by the scope, a 6X Leupold, and after squinting through it at the surrounding mountains, commented in Turkish to the game guard, who translated in Iranian to Hooshang, who passed on in English, “The sheep must now be very careful because they do not know about such a wonderful rifle as this.”

“I think they already know,” I answered, “and they all ran away.”

This must have been precisely the right thing to say because everyone cackled in delight at my fine wit, and we had a parting round of handshaking and chest-patting.

Taking our leave, we crossed the river again and coaxed the horses to the top of another range of hills where we rested and boiled tea over a sagebrush fire. As I sipped my tea Iranian fashion, with a lump of sugar held behind the teeth, and nibbled a chunk of crumbly cheese, I studied the valley and its village and wondered how many caravans, invading armies, and bands of raiding bandits had followed the river’s winding route into this heart of the ancient Persian Empire.

We didn’t see a single sheep all day, but Fred and Manny had located a good-sized herd. When they found them it was too late for a stalk, but they had high hopes for the next day. Despite the lack of game, it had been a fascinating day, and that evening, appropriate apologies to Allah, a bottle of Iran’s famous eye-watering vodka appeared on the table.

The next day dawned cold and still with a high gauze of clouds hinting at a weather change. To the west of camp was a low range of hills, which looked like fairly easy going. Hooshang said that there were lots of sheep there but that the climbing was extremely difficult. An hour later I knew what he meant.

They were not only a lot steeper than they looked from a distance, but also covered with a layer of loose, baseball-sized rocks that made climbing treacherous. Even more bothersome was the free-standing nature of the hills: There were no ridges to follow; instead, each hill had to be climbed, investigated, and descended, one at a time. Thus the day was a muscle-knotting exercise of up and down frustration. Occasionally we would spot a band of sheep, but there was never enough cover for a stalk, and the sheep would scamper off as we tried to slip within rifle range.

Twice we completely circled around the mountains, trying to find a safe approach to the wary sheep, but each time they disappeared. There was nothing to do but keep climbing and hoping.

About mid-afternoon, dead tired and weary of chasing sheep that vanish like wisps of fog, we had just topped an especially grueling mountain and were heading down when the game guard stiffened and pointed into the rocky ravine below. My first thought was that we’d blundered into a bunch of sheep, but instead, I saw only three reddish-brown forms streaking out of the gulch and up the side of the next hill. Wolves!

I wasn’t clear on what the law said about shooting wolves and lost too many seconds questioning Hooshang and the game guard. By the time I got an explanation that wolves were a despised predator and I could shoot all I saw, they had rounded the hill and were out of sight.

But as it turned out my few seconds of hesitation proved to be a stroke of luck.

Five minutes later we spotted three good rams taking their leisure on the crest of one of the closer hills. If I had shot at the wolves (who might have been stalking the sheep, too), the rams would surely have spooked without our even having seen them.

As we studied their position it became apparent they were bedded down where they could watch all approaches to their hill. Any attempt to get closer over such open ground would obviously be foolish and fruitless. Clearly, there was but one option, and Hooshang knew it better than I.

“We can get no closer than 400 meters. Do you want to try a shot?”

I’d already checked the wind direction and other factors that might affect the flight of my bullet and calculated there would be a fishtailing breeze whipping around the hills. I was also aware that one more wounded sheep and my license would be filled.

“Let’s give it a try,” I said.

A half-hour later Hooshang and I had climbed to within a few feet of the pinnacle of a hill closest to the sheep and, flat on our bellies, were inching toward the crest. I slid my rifle ahead of me so it would be very nearly in position as soon as we saw the sheep.

When we peeked over the top the sheep were still bedded down but were alertly scanning the countryside. I’ve never liked shooting at an animal lying down because the angle can fool you, and at a distance of some 400 yards it made the diminutive targets even smaller. One of them took a long, hard look our way, causing us to freeze where we were, but after a tense moment or two he looked away.

Hooshang whispered, “The one in the middle is the best one.”

Moving an inch at a time, I eased myself a bit higher and guided the rifle into a shallow crevice that would serve as a sort of rest. But just at that instant the rams spotted me. In a flash the big ram was on his feet and in another instant he could have been out of sight, but he hesitated for another look in my direction. That was just enough time for me to get the crosshairs above his shoulder and send a 140-grain Nosler on its way before he disappeared.

At the sound of the shot, the game guard scrambled up beside us, and a moment later he was pointing at three rams darting among the boulders at the bottom of the hill and angling toward us.

“Shoot! Shoot!” he yelled.

I had already swung ahead of the lead ram and was about to press the trigger when Hooshang grabbed my arm.

“Don’t shoot! Don’t shoot! Your ram is dead.”

For an instant I thought that he meant one of the rams was hit and didn’t want to risk me hitting the wrong one. But all three looked very much alive as they disappeared from sight.

I suppose I looked like I was about to argue the point, but Hooshang was laughing and explaining what had happened. When I fired, he was the only one who had seen my ram turn a flip and fall dead. The extra ram running away was actually a fourth sheep that had been bedded out of sight.

It took nearly an hour to get down the mountain and scale the hill where the dead ram lay, cleanly hit in the chest and much bigger than we had estimated. Armenian sheep horns that measure 80 centimeters are very, very large indeed. My ram officially measured over 83 centimeters on both sides. (See postscript.)

Fred had his own run of luck that day and had connected on a long shot at a big ram. The sheep didn’t drop in its tracks, and for a while it looked like the ram had gotten away. Fred’s luck held though, and the trackers found the ram that evening and brought it into camp.

We were both luckier than we knew, because that night the weather went bad and piled in several more inches of snow, making any further hunting impossible for several days. Predictably, the plane to Tehran was grounded again, and we forsook another train trip and opted for a long but peaceful drive back to the capital with Hooshang and Manny. One ibex, two Armenian sheep, and one Iranian train ride had been adventure enough.

Postscript: I was later to learn that my Armenian sheep created some problems in the Iranian Game Department. It seems that the Shah’s brother, an internationally known trophy hunter, had issued standing orders for record-class game to be reported to him and kept under surveillance, presumably so he could add it to his personal collection. Somehow my sheep had gone undetected until the day I collected it myself, which resulted in some bureaucrat back in Tehran having a lot of explaining to do. I was not concerned.

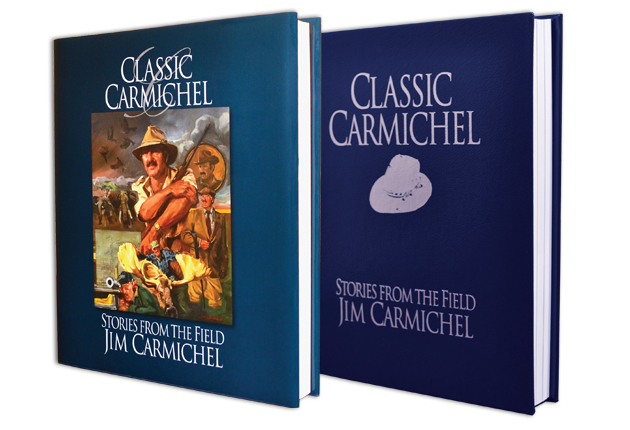

Editor’s note: “The Littlest Sheep” is a chapter in Jim’s new book, Classic Carmichel—Stories from the Field. Bringing together articles from his nearly 40 years as the shooting editor for Outdoor Life, this collection is an indispensable source of wit and wisdom for hunters and shooters. Buy Now

Editor’s note: “The Littlest Sheep” is a chapter in Jim’s new book, Classic Carmichel—Stories from the Field. Bringing together articles from his nearly 40 years as the shooting editor for Outdoor Life, this collection is an indispensable source of wit and wisdom for hunters and shooters. Buy Now