The bets we had made put my much-needed expense money at serious risk. Since I had the responsibility of managing the canoe and could only cast while it was drifting freely, I was at a considerable disadvantage.

You had to admire Jack Fincassel. He was the hardest working man I ever knew. And he expected as much out of those of us who worked for him as he did of himself.

You had to admire Jack Fincassel. He was the hardest working man I ever knew. And he expected as much out of those of us who worked for him as he did of himself.

But jack liked to play, too. He was an excellent tennis player and a first-rate golfer. He regularly shot skeet and trap in the high numbers and was said to be a whiz at the poker table. But, perhaps most of all, he liked to fish for smallmouth bass.

There were half-a-dozen of us on the staff of the small fishery research laboratory in the foothills of the Allegheny Mountains. Fincassel, who had a doctorate in fishery biology from a prestigious southern university, was the chief. I was low man on the totem pole.

Whip thin, and not much more than five-and-a-half feet tall, Jack Fincassel made up for his lack of size by a fiercely competitive nature. And there were few who could best him at his chosen activities. Those who worked under him soon learned that it didn’t pay to compete with the boss. We seldom won.

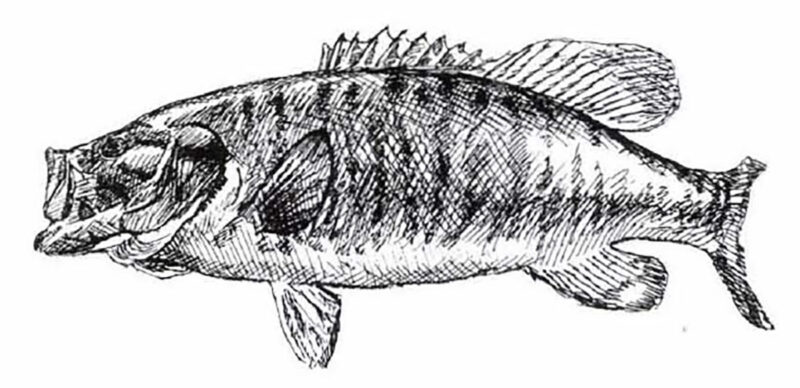

One of our major projects at the lab, and certainly the closest to Fincassel’s heart, was a long-term study of the smallmouth bass population in five area rivers. Six- to seven-mile test sections on each river were studied in detail. Food organisms were collected and evaluated, spawning areas were documented and bass and other fishes were captured and their growth and abundance monitored.

This was in the days when electric shockers were still just a dream in the back of some biologist’s mind, so fish for our study had to be taken by more primitive means. Unlike most river fish, which can be easily caught with a net or trap, small mouth bass are too wary and we had to resort to rod and reel to collect the specimens we needed. It was demanding work, but someone had to do it. Sometimes the boss would let me help.

Immediately after capture, the bass were killed and immersed in formalin. Later, in the lab, we studied their scales to determine age and rate of growth, had a look at their stomach contents and checked for ovarian tapeworms and other parasites.

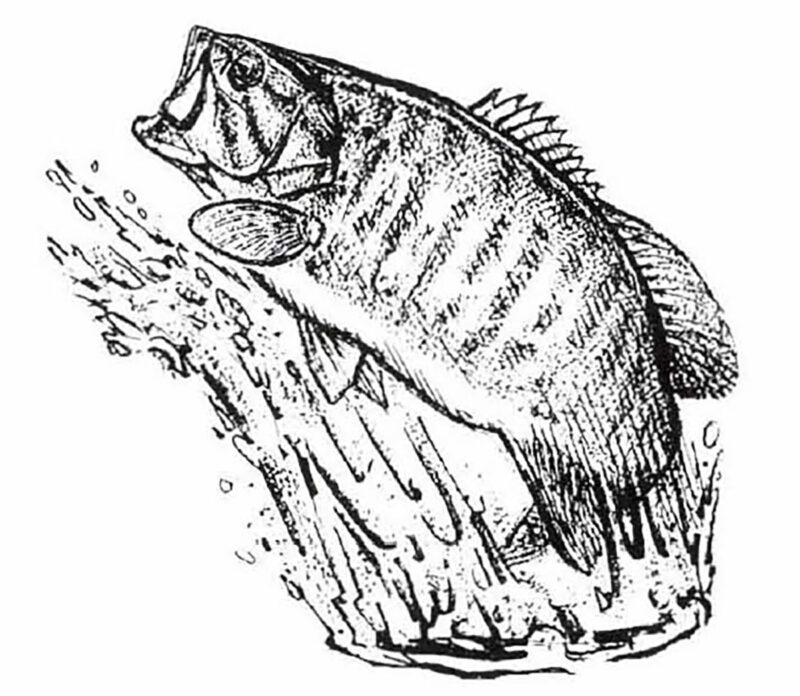

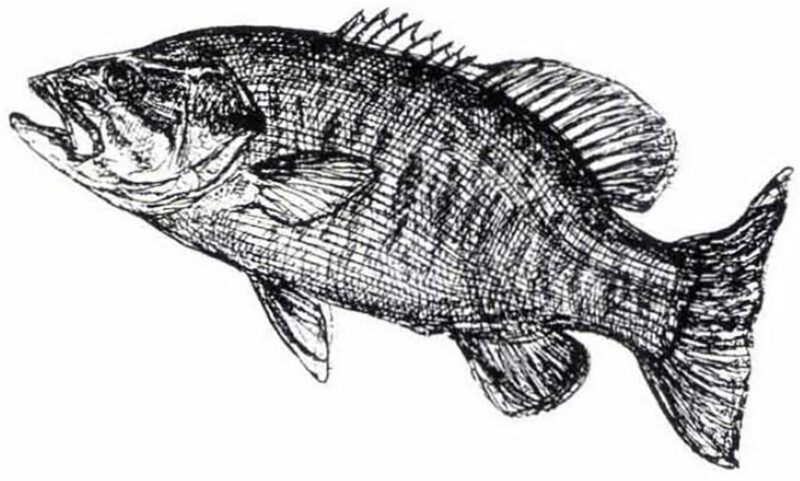

For the study, it was necessary to collect 200 adult smallmouth every year from each test section. Jack Fincassel caught most of them, using a short, stiff casting rod and a free-spool reel loaded with nine-pound test line. His favorite lure was one he called “the little devil.” He would modify a Pflueger Tandem Spinner, a popular lure of that era, by painting the propeller-like blades black and substituting black bucktail tied on tandem treble hooks for the flashy guinea feathers of the original. Since the lure was light in weight, Jack would employ a kind of lasso cast to get sufficient distance, dangling about three feet of line from the rod tip, then twirling the lure rapidly around his head two or three times before letting it fly. He was able to cast great distances with remarkable accuracy. Since most of our bass collecting was done from a 16-foot canoe, the person in the stern had to be constantly on the lookout for Fincassel’s twirling, multiple hooked lure. I wore a fiberboard sun helmet and kept my head low.

A pair of wood ducks screamed away into the mist of an early July morning as we slid the green canvas-covered canoe into the quiet waters of the South Fork of the Shenandoah River a dozen or so miles upstream from Front Royal. We had left a vehicle at the lower end of the test section and planned to pull out around dark, retrieve the other car and make it home before midnight.

Fincassel snapped a little devil lure on the end of his line, kicked his tackle box under the bow seat and stepped into the canoe. I laid my Heddon flyrod along the gunnels, grabbed the canoe pole and pushed us off into the slowly moving current. The water was motor oil-green in the morning light. Small white islands of foam rode the surface.

Jack’s lure whistled as it spun through the air and settled quietly on the dark water. He began a slow retrieve. “Jimmy,” he said, “don’t you think we oughta make a little bet or two before we get started? It makes it more fun, more challenging, you know. And a little friendly competition might keep you from going to sleep in the back of the canoe. What do you say?”

I shoved hard on the pole as a limestone ledge loomed out of the mist and the current quickened. “Yes sir, Jack, whatever you say.” And then, under my breath, “Yes, dammit, you’re the boss.”

“What say we bet half-a-dollar on who catches the first bass and the same for the most, and then the guy who catches the longest bass gets a buck. Okay?” Fincassel didn’t wait for my affirmation. He just kept on tossing his little devil lure.

I stowed the canoe pole under the thwarts and let us drift. In those days we were allowed three dollars a day for expenses if we were away from our home station more than 24 hours. Two dollars for a shorter period. My salary at the time was only 20 bucks a week. The bets we had made put my much-needed expense money at serious risk. Since I had the responsibility of managing the canoe and could only cast while it was drifting freely, I was at a considerable disadvantage. Jack Fincassel made sure he lost very few bets on the river.

Ahead lay half-a-mile or so of flat water with only an occasional rock breaking the surface. As the canoe drifted, I made one short cast after another. Within minutes, a foot-long bass grabbed my Mickey Finn streamer, jumped a couple of times, then seemed to give up and I brought it to the side of the canoe. Well, at least I’ll boat the first bass, I thought, reaching for the leader. But the bass had other ideas and jumped again. The streamer went flying and the fish disappeared.

Fincassel laughed. “I knew you’d lose him. You brought him in too fast. That fish would have been worth half-a-buck to you.” He was casting to the shoreline now and letting his lure sink for a few seconds before starting a retrieve. I heard him grunt and saw him lean back on his rod. In seconds he had a ten-inch small mouth at the side of the canoe and reached over and grabbed it by the lower jaw. He held it high for me to see, then knocked it on the head and dropped it in a can of formalin. “Number one in the can and half-a-buck in my pocket,” he laughed.

Fincassel laughed. “I knew you’d lose him. You brought him in too fast. That fish would have been worth half-a-buck to you.” He was casting to the shoreline now and letting his lure sink for a few seconds before starting a retrieve. I heard him grunt and saw him lean back on his rod. In seconds he had a ten-inch small mouth at the side of the canoe and reached over and grabbed it by the lower jaw. He held it high for me to see, then knocked it on the head and dropped it in a can of formalin. “Number one in the can and half-a-buck in my pocket,” he laughed.

As the mist left the water, the bass became more active. They seemed to like my streamer fly and in a 15-minute period I hooked half-a-dozen or so. All jumped and fought doggedly before coming to my hand. The boss didn’t say a word, just speeded up his retrieves and watched his line more intently. But he took only one small bass during that time.

Soon we came to a series of short, steep riffles and I had to lay my rod down and maneuver the canoe through adifficult stretch of quick water. Jack continued fishing. Soon he boated a nice 14-inch bass and followed it with a smaller one. He was excited now, and his little devil lure was whizzing through the air as he cast again and again to pockets in the fast-moving water.

The canoe hit a submerged ledge and listed sharply. I stood to gain leverage with the canoe pole and my sun helmet fell off. Fincassel’s wildly swinging lure struck me squarely between my nostrils, one barbed hook driving completely through. It felt like the blow of an axe.

I fell to my knees and the canoe broached in the current. Water poured over the gunnels. Jack grabbed a paddle and pushed us against a protruding ledge and held us here. Stunned, I lay on the bottom of the canoe, my hands covering my face.

Fincassel jumped out into knee-deep water and pulled the canoe up on the ledge. “Jesus Christ, Jimmy, you shouldn’t have stood up. Here, let’s have a look at you.” He pulled my hands away from my face. Blood streamed from my nose. “Oh, it’s not really so bad.” he said. “Only one hook has gone through. We’ll get you to a doctor and you’ll be okay in a few days. Here, hold still while I cut the line and see if I can unhook the spinner blades.”

But it wasn’t easy, Fincassel tugged and pulled on the lure as gently as he could, but the pain was intense and I winced and pulled away from him. He somehow got the spinner blades disconnected. But the tandem-hooked black bucktail hung from my nose like the ring on a Jersey bull. It felt like a 10-pound weight. My shirt was red with blood.

I climbed out on the ledge while the boss tipped the canoe and let the water flow out. “Let’s get going,” he said, as he returned to his seat in the bow. “We’ve got a good five miles to go and a lot of bass to catch. Keep the old chin up, Jim. We’ll get you to a doctor before you know it.”

Holding a handkerchief over my nose with one hand, I picked up a paddle with the other and began slowly stroking us downriver. Fincassel kept casting. “Take it over by that gravel bar, Jimmy,” he called out. “That’s where the bass’ll be feeding this time of day.”

The sun hammered us mercilessly that torrid July day as we slowly drifted. Jack kept tossing one bass after another into the formalin can, while I steered as best I could. In late afternoon, I fashioned a sort of sling out of my handkerchief and stabilized the hanging bucktail-covered hooks. My nose stopped bleeding and I began making casts to the shoreline. The bass were cooperative and, in a short time, I added four to the formalin can.

We were within sight of our pullout location when I saw a fish chasing minnows in the shallows. I carefully edged the canoe as close as I dared and laid out a long cast. The bass took as the fly kissed the water, jumped a couple of times, searched the deep water in the middle of the river for a minute or two, then came grudgingly to my hand. Fincassel looked around as I boated it, but didn’t say a word. I measured the fish and slid it into the can. “Nineteen-and-a-quarterinches,” I mumbled through the bloody handkerchief. “It’s the biggest fish of the day.”

Jack kept casting as I paddled the canoe through the last couple hundred yards of water, his little devil sailing out into the darkening water. Then, just as I was preparing to slide the canoe up on shore, he made a long, looping cast out into the river. His lure stopped and he set the hook. For a time the fish wouldn’t show itself, just bulled its way out into the current. “Big old catfish, maybe.” Jack leaned back on his rod but failed to gain line. “More likely I foul-hooked a carp,” he grunted.

But it wasn’t a carp or a catfish. Five minutes later Jack lifted a 22-inch smallmouth out of the water. He looked at me and grinned as he knocked it on the head and slid it into the formalin. “Come on, let’s get going. We’ve got to get you to a doctor.”

A couple of hours later we pulled into the garage at the lab. The hooks were gone, and my sorely swollen nose was packed with cotton. As we unloaded our gear, Jack turned to me and said, “You know, Jimmy, I caught 27 smallmouth today while you took less than a dozen. That’s 50 cents you owe me. And remember, I took the first one. That’s another half-a-buck. And that 22-incher beats anything you got. So you owe me two dollars.”

A couple of hours later we pulled into the garage at the lab. The hooks were gone, and my sorely swollen nose was packed with cotton. As we unloaded our gear, Jack turned to me and said, “You know, Jimmy, I caught 27 smallmouth today while you took less than a dozen. That’s 50 cents you owe me. And remember, I took the first one. That’s another half-a-buck. And that 22-incher beats anything you got. So you owe me two dollars.”

For a moment I lost my temper. “For Christ’s sake, Fincassel,” I yelled, “you’re not going to collect on those stupid bets after all the problems I’ve had, are you?”

“No, no, James, my boy,” he said in a kindly voice, “not right now anyway. Just wait until your monthly expense account check comes. You can pay me then.”

Through a series of nearly 50 personal essays, the author explores what happens when the self-taught, DIY angler sets out to fish the world—and winds up stumbling into every possible pitfall and danger along the way. These include: getting chased from a river by an elephant, surviving a terrifying helicopter ride over the Straits of Magellan, and breaking his only rod on the second cast in Cuba’s Bay of Pigs.

Through a series of nearly 50 personal essays, the author explores what happens when the self-taught, DIY angler sets out to fish the world—and winds up stumbling into every possible pitfall and danger along the way. These include: getting chased from a river by an elephant, surviving a terrifying helicopter ride over the Straits of Magellan, and breaking his only rod on the second cast in Cuba’s Bay of Pigs.

Closer to home, he is swept off a jetty on Block Island by a rogue wave, winds up in an emergency room more than once with fishing lures hanging from various parts of his anatomy, and perhaps most daunting, surviving 30 years of the scrum better known as opening day of trout season in his crowded home state of New Jersey. Buy Now