Jim Casada contemplates the art and romance in the literature of turkey hunting and the world of sporting, wildlife literature at large.

The malady of bibliomania exhibits varying symptoms. Some collectors are perfectly happy to do little more than gaze on lovely yet lonely leather-bound volumes residing as dust-laden prisoners in glass-fronted cages while never being read. Others not only read avidly, they pencil notes in page margins, fold corners to mark their place, rest coffee cups where a bit of brew has overflowed atop book covers and otherwise wreak havoc when it comes to any meaningful material value for the works they peruse. Then there are the showboats among bibliophiles—those who accumulate representative holdings and treat them with care, all the while missing what I personally consider most important; namely, they own books, care for them well and display them proudly. Sadly, they seldom do any actual reading. When it comes to sportsmen who cherish books, there are those belonging to each of the categories just described along with individuals characterized by countless other predilections.

The malady of bibliomania exhibits varying symptoms. Some collectors are perfectly happy to do little more than gaze on lovely yet lonely leather-bound volumes residing as dust-laden prisoners in glass-fronted cages while never being read. Others not only read avidly, they pencil notes in page margins, fold corners to mark their place, rest coffee cups where a bit of brew has overflowed atop book covers and otherwise wreak havoc when it comes to any meaningful material value for the works they peruse. Then there are the showboats among bibliophiles—those who accumulate representative holdings and treat them with care, all the while missing what I personally consider most important; namely, they own books, care for them well and display them proudly. Sadly, they seldom do any actual reading. When it comes to sportsmen who cherish books, there are those belonging to each of the categories just described along with individuals characterized by countless other predilections.

Yet for all the diversity of collectors and differing manifestations of bibliomania, there is considerable common ground when it comes to the love of sporting literature. The fact that this magazine has been around for the better part of four decades attests to that, and over what seems an incredible time span (mainly because I’ve been a part of Sporting Classics for virtually all of it) adjunct endeavors have witnessed the publication of books aplenty. Books are a pleasant, rewarding refuge in times of trouble; when one simply feels a need to escape from the hurly burly of everyday existence; or when a spate of armchair adventure seems to be just the ticket. In that regard I would be less than honest if I didn’t acknowledge some qualms about the future of the printed word, at least in the form of solid, hefty volumes you can feel, enjoy visually and at least in the case of leather bindings, even smell. Let’s hope my fears are badly misplaced.

Whatever the future holds for books as we have long known them, I readily recognize that not all sportsmen are avid readers, especially when it comes to book-length treatments. Similarly, there’s no denying that some branches of outdoor endeavor draw far more readers than others. Although it would probably be difficult to quantify, my gut feeling, backed to no small degree by the sheer quantity of published volumes in the field, is that fly fishermen are the keenest of all sporting readers. Upland bird hunting and bird dog devotees don’t lag too far behind, while decent volumes devoted to small game animals such as rabbits and squirrels have always lagged and of late seem to be in abject decline.

That brings us to a category of sporting literature that holds a special place in my personal interests—turkey hunting. Thanks primarily to the splendid comeback story of America’s big-game bird, although there are troubling signs in the form of dramatic population drops over wide ranges in recent years, books on turkey hunting have multiplied in a most gratifying fashion in the last half century. From the point when the first full-length work devoted exclusively to the sport appeared in the second decade of the past century (you can read about that strange, and in some ways sordid saga elsewhere in this issue) until 1950, literally less than a double handful of meaningful books dealing with turkey hunting had seen the printed light of day.

That brings us to a category of sporting literature that holds a special place in my personal interests—turkey hunting. Thanks primarily to the splendid comeback story of America’s big-game bird, although there are troubling signs in the form of dramatic population drops over wide ranges in recent years, books on turkey hunting have multiplied in a most gratifying fashion in the last half century. From the point when the first full-length work devoted exclusively to the sport appeared in the second decade of the past century (you can read about that strange, and in some ways sordid saga elsewhere in this issue) until 1950, literally less than a double handful of meaningful books dealing with turkey hunting had seen the printed light of day.

Over the ensuing six decades, that number skyrocketed. A decade ago, I wrote and self-published a slip-cased, numbered, limited edition of a book bearing the title The Literature of Turkey Hunting: An Annotated Bibliography and Random Scribblings from a Sporting Bibliophile. It contains 580 entries and in all likelihood the ensuing 10 years have seen the appearance of at least 100 additional books devoted exclusively or in appreciable measure to turkey hunting. By any standard of measure, that’s a huge change.

The quality of modern books on turkey hunting, whether judged from the standpoint of readability, collecting value or other measures of quality varies tremendously. No small part of that comes from the fact that increasingly they are self-published. One major problem inherent in the entire self-publishing movement is that anyone who can afford the up-front costs can become an author overnight, and with print-on-demand, deep pockets aren’t required. Alas, in the turkey hunting genre there have been more than a few such titles that can only be described as travesties. I’ll offer as a particularly egregious example one author who has seen fit to burden the turkey hunter’s world with several books, although admittedly this is an extreme case. For starters, the author’s name on the title page of his books is preceded by “Mr.” In my experience that’s unique. Then there are virtually endless excursions into creative spelling. In one book the title speaks of “Storys from the Field” while in the title of another one the word novice is offered as “Novas.” Within the text of his books (and there are a half dozen or so of these abominations in the turkey field along with others on hunting wild hogs) a graveyard is a “cemitary,” beginning is offered as “beging,” pursuit as “persuit,” private as “privet,” beats as “beets,” along with so many other highly creative renditions you almost have the raw material for a textbook. On top of that, the books contain enough stylistic and grammatical problems to send a well-meaning English teacher on the fast track to either insanity or paroxysms of rage. I’m both a serious reader of turkey books and someone who tries to collect all new titles in the field, but in this case I threw up my hands in dismay and said “no more.”

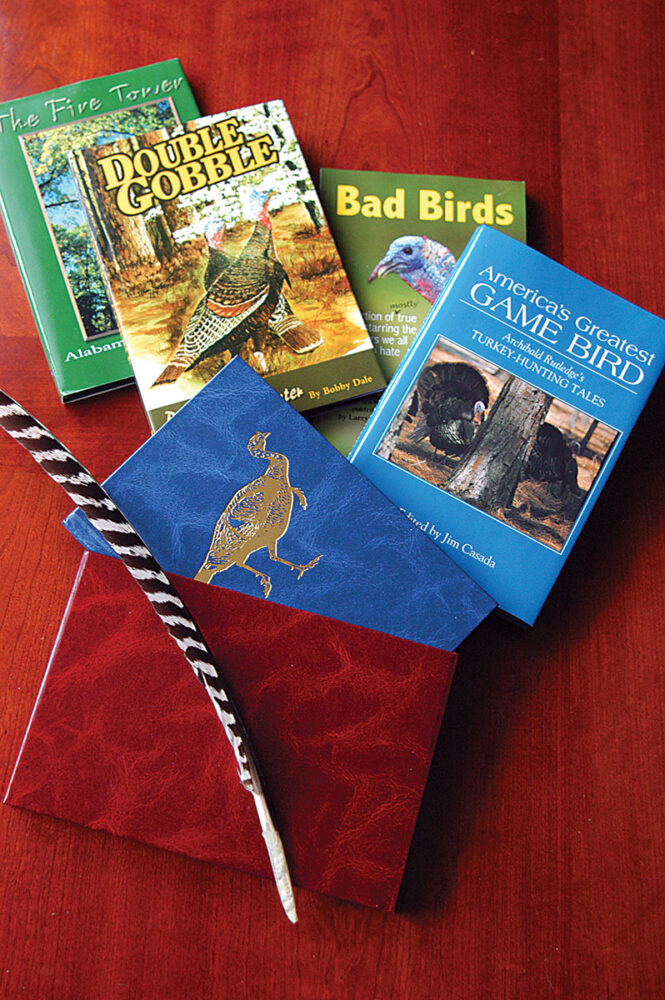

On the other hand, thankfully, some truly first-rate turkey books, featuring interesting and informative material from authors such as Bobby Dale, Jim Spencer, Ron Jolly, Gary Sefton, Otha Barham and numerous others, have been self-published. Even the man sometimes referred to as the poet laureate of the wild turkey, Tom Kelly, has traveled that trail for all of his more recent works. In truth, it’s pretty well necessary. The spectrum of commercial sporting publishers in general has narrowed a great deal in the past decade, and off the top of my head I can only think of a couple of them likely to touch anything turkey-related other than possibly works of the hardcore how-to genre.

On the other hand, thankfully, some truly first-rate turkey books, featuring interesting and informative material from authors such as Bobby Dale, Jim Spencer, Ron Jolly, Gary Sefton, Otha Barham and numerous others, have been self-published. Even the man sometimes referred to as the poet laureate of the wild turkey, Tom Kelly, has traveled that trail for all of his more recent works. In truth, it’s pretty well necessary. The spectrum of commercial sporting publishers in general has narrowed a great deal in the past decade, and off the top of my head I can only think of a couple of them likely to touch anything turkey-related other than possibly works of the hardcore how-to genre.

That’s argument aplenty for self-publishing, and with careful proofreading, due attention to detail and utilization of a printer who does things right, such books can be dandies. After all, the sport is one that lends itself to the telling of tales, a medium where the storyteller’s craft can flourish. Those who write such books, no matter how skilled, have little if any recourse other than to take the self-publishing path. The end result may not make the author rich, but he can get his cheese back and then some while enjoying the inner satisfaction of having left something meaningful for literary posterity. Those of us who are readers are the true beneficiaries, however.

That’s pretty much the reality of things in the reading turkey hunter’s world today, and indeed it represents one of the conundrums connected to self-published works no matter what the subject matter. Serious readers have to do more searching to find worthy new books, because a major drawback of most self-publishing endeavors is promotion. An individual simply does not have the potential clout or audience reach of an established commercial publisher with publicists, lists of review outlets, sophisticated websites and the like. That translates to a reduced likelihood of potential book buyers knowing about the work, just as the absence of expertise in editing, fact-checking, access to quality printing and binding, along with other considerations, stare self-publishing authors squarely in the face.

The world of sporting book publishing in general has changed dramatically of the past generation, and what is happening with the literature of turkey hunting is a microcosm of a much larger whole. It’s interesting, challenging for author and reader alike, and involves a major new dimension in the collecting of sporting books. Still, with the proper mindset that’s cause for delight rather than dismay. Serious bibliophiles have always welcomed a challenge, and keeping abreast of developments in this field certainly presents one.

The world of sporting book publishing in general has changed dramatically of the past generation, and what is happening with the literature of turkey hunting is a microcosm of a much larger whole. It’s interesting, challenging for author and reader alike, and involves a major new dimension in the collecting of sporting books. Still, with the proper mindset that’s cause for delight rather than dismay. Serious bibliophiles have always welcomed a challenge, and keeping abreast of developments in this field certainly presents one.

Recently, Ken Callahan, a noted purveyor of out-of-print sporting books, quoted in one of his catalogs a comment on wild turkeys offered by William Elliott a century and a half ago in his Carolina Sports By Land and Water: “Everything connected with the modes of shooting them, or capturing them, has been so often noticed by others, that to refer to these topics here would seem to be but a useless repetition.” Pretty obviously Elliott, for all the enduring appeal of his book, was woefully wide of the mark when it came to the literature of turkey hunting and failed miserably as a literary prognosticator. For my part, I’m thankful he was wrong. I’ll continue enjoying the quest for new books in the field, recognizing as I do so that times are changing, and changing dramatically.

In Remembering the Greats, a 317-page hardbound book, Jim Casada brings his training as an historian, his decades of studying the grand masters of the sport, his avid collecting of the literature, and his personal hunting experiences to bear in a detailed examination of the careers of 27 icons from turkey hunting’s past. Collectively they epitomize the essence of what old timers sometimes refer to as true “turkey men.” Buy Now

In Remembering the Greats, a 317-page hardbound book, Jim Casada brings his training as an historian, his decades of studying the grand masters of the sport, his avid collecting of the literature, and his personal hunting experiences to bear in a detailed examination of the careers of 27 icons from turkey hunting’s past. Collectively they epitomize the essence of what old timers sometimes refer to as true “turkey men.” Buy Now