Fall is fading fast. Naked branches click like dry bones in the wind, and the choppy, pewter-toned lake mirrors an apocalyptic sky. Winter’s wrath brooks no quarter when the wicked weather turns minutes into hours, and few know its fury better than the late-season duck hunter.

For centuries, Ottawa natives knew this floodplain as Macatawa, but practical-minded Dutch settlers later renamed it Black Lake. Its wide, turbid waters stretch nearly seven miles between the inlet and the channel leading out to Lake Michigan. In November, Mac grows mighty rough on windy days, but its fury pales in comparison to the Big Lake, where swells often top 20 feet or more. During those chaotic pre-winter storms, ducks flee the tossing waters for Macatawa’s sheltered coves.

The man had lived along Black Lake for all his 68 years. Gazing through the kitchen window that morning, he strained to see the blinking red beacon at Middle Ground, but sideways sleet obscured his view. As he poured a second cup of coffee, flocks of butterballs and bluebills skirted the near shoreline in search of calmer waters. Days like these were best spent beside the woodstove with a whiskey in one hand and a copy of Buckingham in the other.

Unless you lived to square off with the brittle cold and driving wind.

Unless you hunted ducks.

Shoulders hardened from a lifetime of rowing and a ruddy complexion marked the man as a longtime wildfowler. Never in 50-odd years had he missed a chance at post-Thanksgiving ducks, and today was no exception.

A short, easy hunt. That’s what whirled through his mind as he swung the sack of decoys into the truck and drove to a nearby cottage. The neighbor who owned this summer home allowed the man to store his battered wooden rowboat on the beach for easy access. Like so many others around the lake, the cottage was dark and vacant through the off-season. On its windswept shore, the overturned dory blended in with a virtual armada of boats that wouldn’t see water again until Memorial Day weekend.

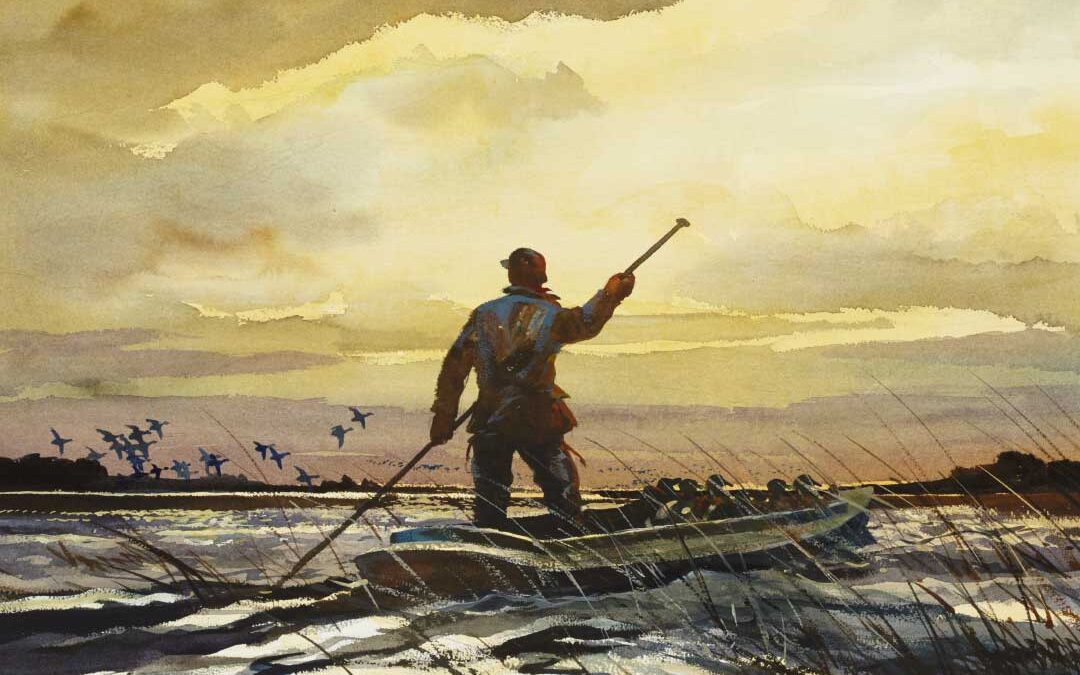

Artwork by Chet Reneson

The man’s waxed-cotton jacket with its heavy wool collar felt like cardboard, but the stiff fabric deflected the sharp wind and icy snow. Pawing through a side pocket, his fingers found a dozen 12-gauge magnum shells. Late-season divers wear a thick layer of fat and feathers, and heavy #2s were just the medicine to penetrate their armor.

Given the strong wind, the ducks would fly no matter what; decoys were more affectation than a necessity, but part of this seasonal ritual, nonetheless. Just a handful of shotshells and a dozen decoys, that was all; these late-season, foul-weather hunts were a minimalist’s game indeed. With a bit of luck though, he’d have his share by sundown.

Before shoving off, he grabbed a life vest and headlamp. “Little things are important in late-season hunting,” his father had always chided. Dad was long gone now, but his wisdom lived on. At this unforgiving time of year, even minor mistakes had a way of turning troublesome, even treacherous. But the man enjoyed these threadbare outings best of all.

Even after all these years, the raw, unforgiving weather always left him wide-eyed and slack-jawed. Nothing made him feel more like a real duck hunter than being out there among the bobbing blocks and ivory-rimmed rollers. The snow and wind and whipping water thrust him headlong into the thick of things, like some salty old bayman in a Homer painting.

The late-afternoon sun shone pale in the western sky as the man muscled the dory down the sandy beach. Stowing the dekes amidships, he waded out into the chop. Almost immediately, the cold crept through his thick neoprene waders. He smiled in spite of the temperature as divers traded back and forth across the mile-wide bay. The magic hour was at hand. Sleet reddened his cheeks as he rowed, and the waves lapped against the wooden hull with a rhythmic schlop-schlop-schlop. The northwest wind kept nudging him off track and he compensated with deliberate port-side strokes to hold the course.

When the Middle Ground Light loomed into view, he knew he’d arrived. The rounded concrete pylon rose 10 feet above the lake’s surface like a miniature lighthouse. As the name implied, Middle Ground marked the center of the lake—the channel lay three miles to the west, the inlet three miles to the east, and a half-mile of open water separated the north and south shores on either side. Lake Mac ran notoriously shallow, but in 1909, the Army Corp of Engineers dredged-out a shipping lane to allow the passage of barges and freighters. The blinking red beacon at Middle Ground marked the course and kept the ships from running aground.

Unraveling nylon cords, the man clipped each decoy to a mother-line anchored 25 feet beneath the surface. Hardly enough weight for wind like this, he mused, but the blocks stayed put and looked convincing enough in the wan light of evening. The stage was finally set. Now it was time to enjoy a pipe, but searching his shirt pocket, his fingers found only a hole where the Zippo should have been. The heavy brass lighter must have migrated down into his waders. To retrieve it, he’d have to stand up, and that meant making a pit-stop at Middle Ground. Was all the rigmarole really worth the fuss? Yes it was, he decided. Like the decoys, smoking Dad’s old pipe was tradition on these hunts. And besides, he’d welcome the bladder break.

Navigating alongside the pylon, a flock of bluebills tore by on a tailwind that threatened to snatch his hat. The wooden bow grated over jagged chunks of concrete and he dismounted. After dragging the boat farther up the riprap, he wedged the shotgun firmly in the bow, unclipped the wading belt and suspenders and retrieved the lighter. Working quickly, he wasted no time worming back into the protective warmth of wool and neoprene.

As he dressed, he ran through a mental checklist. Details made all the difference in late-season hunting: Neglect the gun and it would jam; leave the mother-line at home and the decoys would float away; forget to wear long underwear and shiver all day; capsize in the frigid water and drown. Some of details represented mere inconveniences; others amounted to a death sentence.

He’d almost run through the entire list when the unthinkable happened. In the scant seconds he had his back turned, a big wave slammed into the riprap, washing the boat back into the water. When he first noticed it, the dory was floating near the far edge of the concrete blocks. Leaning out precariously, he wobbled over the yawning blackness, but the boat drifted just out of reach. In a panic, he tore off his ducking coat and swiped uselessly at the gunwale, but only succeeded in soaking the jacket and pushing his salvation farther away.

In hindsight, he should have lunged for it. He should have dived in, embraced the icy-cold water, and rowed home as fast as his hypothermic shoulders could have carried him. But he didn’t, and the opportunity passed quickly as the wind quickly pushed the vessel out and away.

A wave of disbelief and panic washed over him, like stumbling down a flight of stairs. First came an abbreviated gasp, then a flip-flopping deep in the pit of his stomach.

It’s not the big things that’ll get you into trouble, his father’s voice echoed inside his head; little things can be a late-season duck hunter’s undoing.

Icy shrapnel shuuuushed against the concrete as the rowboat faded into the dimming gray. A taste like rusty nails filled his mouth; the flavor of fear.

The man gazed out over the water at the distant, glowing cottages. Maybe someone will find the empty boat and come looking, he thought hopefully, but quickly dismissed the notion as wishful thinking. Even if the dory didn’t ship water over the side and sink, no one would find it for days, maybe even weeks. Hours were all he had, and no one knew he’d been banished out there on his own private Alcatraz.

Until then, he’d maintained his composure, but chaos consumed him now. He screamed himself hoarse in a moment of primal panic. Volume is irrelevant in wind that carried your cries away like a predatory bird. Useless, he seethed between clenched teeth. USELESS!

In lulls when the gales died, he heard the lake pulsing and breathing like a faraway freighter. Then he prayed, pleading to God with all his might. He’d endured much colder conditions in the past, but there were other factors at play here. Nothing cooled a man’s core temperature like the destroying angels of wind and wetness.

Hours passed. The man cowered low on the leeward side of the column, resting his trembling torso against cold concrete. Retreating deeper into his rag-wool sweater, he shivered violently. The damp old ducking jacket lay useless beside him. He idly checked the pockets but only found shotshells, but the gun was in the boat, and the boat was long gone.

For a moment, he considered cutting open the shells and using the Zippo to torch the gunpowder as some sort of feeble distress signal. Then again, what could they provide—a second or two of light and heat? Surely no one on shore would notice. Countless reflections dotted the lake’s chaotic surface, and a few, brief flashes would simply blend in with lights along the shoreline.

Greenish-black waves hissed against the concrete like hungry serpents. As huddled there alone, his thoughts returned to countless sunrises in far-flung marshes; of the searing hiss of redheads bombing the blocks; of mallards and blacks coming in on cupped wings. Smiling in spite of his situation, he recalled mornings when cigar smoke mingled with the aroma of bacon and eggs sizzling on the little camp stove. These snippets of a sporting life brought solace to his soul. They might have been little things to some, but they represented a lifetime of memories to him.

Suddenly, he wasn’t cold anymore. He was calm . . . everything would be all right. The shivering stopped and he felt warm and relaxed, euphoric even. A flock of bluebills scudded by, bound for calmer waters. Their wings filled the air with the sound of tearing silk. Scaup always were his favorites. They were the last things he remembered before slipping into that deep, dreamless sleep that comes for all duck hunters after a long day on the water.

This article originally appeared in the 2019 November/December issue of Sporting Classics magazine.