Long after his death, Charles Cottar’s legend lives on in the safari world.

Charles Cottar was born in Iowa in 1874, the great-grandson of the first white settler in Cedar County. Before the turn of the century his family moved south by covered wagon, first to Kansas, then later to Oklahoma. The Cottars were among the early homesteaders who staked out land in the Cherokee Strip when the Indian Territory was opened up for settlement.

Charles Cottar was born in Iowa in 1874, the great-grandson of the first white settler in Cedar County. Before the turn of the century his family moved south by covered wagon, first to Kansas, then later to Oklahoma. The Cottars were among the early homesteaders who staked out land in the Cherokee Strip when the Indian Territory was opened up for settlement.

Charles modeled his early life after that of his trailblazing heroes, Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett, wearing his hair long in frontier fashion and hunting wild game with an old-fashioned musket. He soon grew to stand a brawny six-foot-four. His insatiable wanderlust, combined with his fast draw and dead aim, led him to Texas where he served a spell as a two-gun sheriff. Several years later he moved back to Oklahoma where he married and settled down for a while, though his maverick thirst for adventure remained unquenched. In 1910 Cottar pulled up stakes and set off on a solitary mid-life pilgrimage to Darkest Africa. At the start of that fateful journey, none would have guessed that Charles Cottar was destined to gain fame as the first American-born white hunter in East Africa, and that his name would be indelibly etched in the annals of safari lore.

The spark that fired Cottar’s imagination and propelled him out of his own country and onto the shores of a primitive wilderness rose out of the blaze of publicity that heralded Teddy Roosevelt’s 1909-10 hunting expedition in Africa. As newspapers around the globe trumpeted the myriad mysteries of Africa, Cottar vowed to see the land of King Solomon for himself. By the time Roosevelt’s cavalcade had reached the white rhino country along Uganda’s Nile Valley on the last leg of a thirteen-month trip, Charles Cottar had packed his guns and was on the high seas, steaming toward the tropical green waters of the Indian Ocean.

Cottar’s voyage ended at the old Arab port of Mombasa, gateway to the British East Africa where he boarded a railway carriage that would carry him 320 miles inland to the territory’s capital. At Nairobi the Oklahoma plainsman found himself in a dusty settlement where men still packed pistols, wore Stetsons and traveled by horseback or rickshaw. Among its powerful attractions for Cottar, Africa’s frontier town had one feature which surpassed all others: it was smack in the middle of a sportsman’s paradise. Lions strolled the back streets, while Cape buffalo wallowed in papyrus swamps near the celebrated Norfolk Hotel, and elephant often plundered vegetable gardens. From almost any place in the town countless wildebeest, Coke’s hartebeest, zebra, Thomson’s and Grant’s gazelle, eland, wart hog and ostrich could be seen on the surrounding plains.

In Cottar’s day there was no requirement that a white hunter accompany a visitor on safari. The only condition was that a basic game license be purchased. Lion and leopard were considered “vermin” and could be hunted by anyone prepared to gamble his life. Graveyard headstones bearing epitaphs such as “killed by a lion” or “killed by a buffalo” bore ample testimony to the bloody deaths suffered by greenhorns who tangled with the Big Five on their own. Yet danger was a magnet to Charles Cottar, and instead of a white hunter, he cut expenses by hiring an African neapara (headman). The old neaparas were invaluable characters who had once marched at the head of slaving caravans or guided famous explorers to the interior. They kept the safari porters in line if need be, often with the strong-armed aid of a kiboko, a stiff whip made of hippo hide. But neaparas shared one failing: they were not hunters, and knew little about the habits of game, stalking or judging trophies. These tasks were left to gunbearers who came from specialized hunting tribes, such as the WaKamba.

At Nairobi railway station Cottar and his thirty porters, along with three riding mules, a half-dozen pack donkeys, tents, chop boxes, kerosene lanterns, skinning knives, trophy salt, medical supplies, bedding, machetes and axes were loaded on boxcars of a slow goods train bound for a station called Kijabe. As the train rumbled to the edge of the Great Rift Valley at 6,500 feet, Cottar was stunned at the enormity of the panorama far below. Two extinct volcanoes studded the valley floor, surrounded by golden grasslands carved with dry streambeds lined with thickets of yellow-barked acacia. In the distance a blue haze of mountains beckoned.

Charles and his men followed a hand-drawn map supplied by Leslie Tarlton, the Australian white hunter who had outfitted his safari. Their route led to the freshwater lake at Naivasha, then beyond to a string of shallow soda lakes where every variety of bird and mammal could be found. On the grassy plains of Masailand, Cottar hunted rhino, then spoored buffalo in brushy gorges at Hell’s Gates. Charles marched to the 6,000-foot Laikipia Plateau, home to huge herds of game. As his safari edged around the forested slopes of the Aberdare mountains, Charles knew his search was over, and he had found the big game hunter’s Holy Grail.

Back in Nairobi, Bwana Carter, as he was now known, heard tales of giant tuskers deep in the rainforests of the Belgian Congo. The Congo was irresistible to hard-bitten adventurers who hankered to hunt for excitement and profit, without the bothersome expense of game licenses. On the west bank of the Nile at a place called Lado, a wedge of land was the center of a territorial dispute between the Belgian and British. The poachers seized upon the dispute to operate in Lado, poaching ivory from under the noses of the Belgians, secure in the knowledge the British would ignore their shenanigans.

Poaching in the Congo was dangerous work, and several hunters died there. Frequent dust-ups with vigilant Belgian patrols sometimes ended in deaths or arrests. A famous poacher named Billy Pickering was killed by an elephant that tore his head off and the trampled his body to pulp. Another poacher by the name of Broom was shot dead by authorities. Belgian Askaris had once wounded the greatest ivory hunter of all, Walter D. M. “Karamojo” Bell, as he sat in a canoe midstream in the Nile. Ironically, bell was one of the few hunters in the Congo who was legitimate, having taken the trouble to buy licenses. The Askaris paid a price for their temerity, for Bell returned fire with his 7mm rifle.

In the Congo’s great Ituri forest, a region not much better known today than in Cottar’s time, Charles made friends with the Efe pygmies. They alerted him to Belgian patrols and showed him how to hunt at close range in the thickest jungle. With their skillful help Cottar accumulated a sizable grubstake of ivory. But elephants and Belgian Askaris were only part of the risk. Charles left the Congo with deadly spirillum tick fever. Comatose, he was carried by his native bearers over 400 miles to the shores of Lake Victoria, and then 200 miles by train to Nairobi. He survived this extraordinary journey and recovered, but the effects of the disease remained with him to the end of his days. His life was saved only by the endurance and tenacity of his African safari crew.

For the next few years Cotta traveled back and forth between Africa and the United States. In 1915 he packed up his wife and nine children and left Oklahoma for good. A few miles northwest of Nairobi, Charles carved out a new homestead where he built a tropical bungalow-style house. The comfortable home was built on stilts, using wood and corrugated iron sheeting.

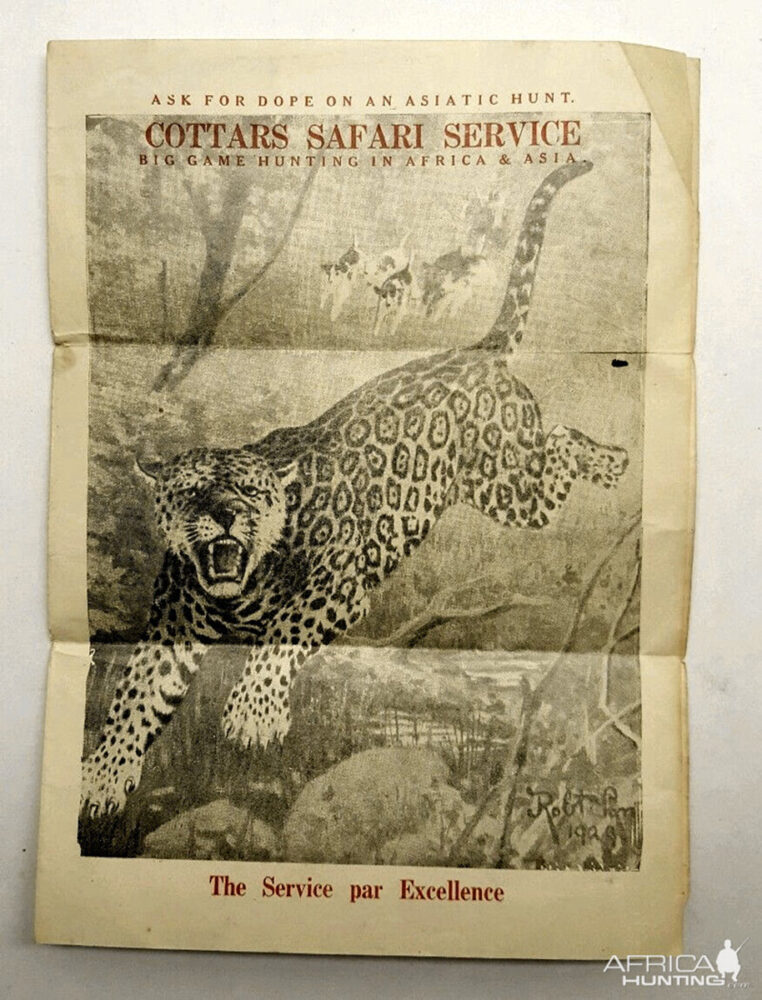

After the first World War, Charles founded his now famous Cottar Safari Service. He returned often to hunt the game-filled plains of Masailand, and took to referring to the entire region as “Cottar Country.” Those who entered his self-proclaimed territory did so at their own risk. His eldest daughter, Evelyn, recalled that he once “shot a few holes into the roof of a car that came into his country. They left in a hurry!” Although Bwana Carter was among the first to import Ford cars to Kenya, he favored riding mules for hunting. Charles built frames on his safari trucks and covered them with mosquito netting in order to transport his prized mules into big game areas. To reach certain parts of Cottar Country, it was necessary to leapfrog perilous “fly belts” inhabited by fierce tsetse flies, whose bites were lethal to domestic stock, and sometimes humans.

One day while hunting with a Winchester .30-06 for meat, Bwana came upon a leopard feeding on a guinea fowl. Cottar fired at the cat, but before he could reload the leopard swarmed all over him, biting him savagely, on the shoulders and face. With his great strength, Cottar used his rifle as a stave to throw off the cat. To his amazement the leopard lay dead where it fell, having succumbed to his bullet. It would be the lightest of three leopard maulings he would experience.

Sometime later Cottar spotted another leopard in open country, and this time he ran it down on horseback. He lassoed the winded beast around the neck, then dismounted and hobbled its hind legs. Leaving the leopard to recuperate, he went to get his motion picture camera. Charles instructed his wife Anita to crank the film and young son Mike to stand guard. Bwana planned to star in the first real-life action movie of a man tussling with a leopard.

As the camera rolled and Charles boldly advanced, the great cat, still hobbled, made a powerful lunge. Cottar swung up his rifle, but the snarling feline knocked him to the ground before he could shoot. Charles wrestled with the leopard and then fired a fatal shot. In those few short moments the cat had done great damage. Doctors told Cottar he had blood poisoning, and insisted on amputating his leg to save his life. He refused, and to everyone’s surprise but his own, Bwana recovered. Anita never lived down the fact that the movie was out of focus and useless.

During his years as a white hunter, Charles and two of his sons offered unprecedented international hunts that began in Africa and ended in India or Indochina. He saw no difficulty in shipping his gunbearers and crews, along with safari vehicles and tentage, to the Far East. He once arrived at the foot of a nearly impassable range in India. Cottar dismantled his cars and had them carried up the escarpments on the backs of elephants, then reassembled them on a plateau, ready for the hunt. These logistical exercises boggle the mind. Considering the great distances and modes of travel at that time, it was an unparalleled accomplishment in outfitting.

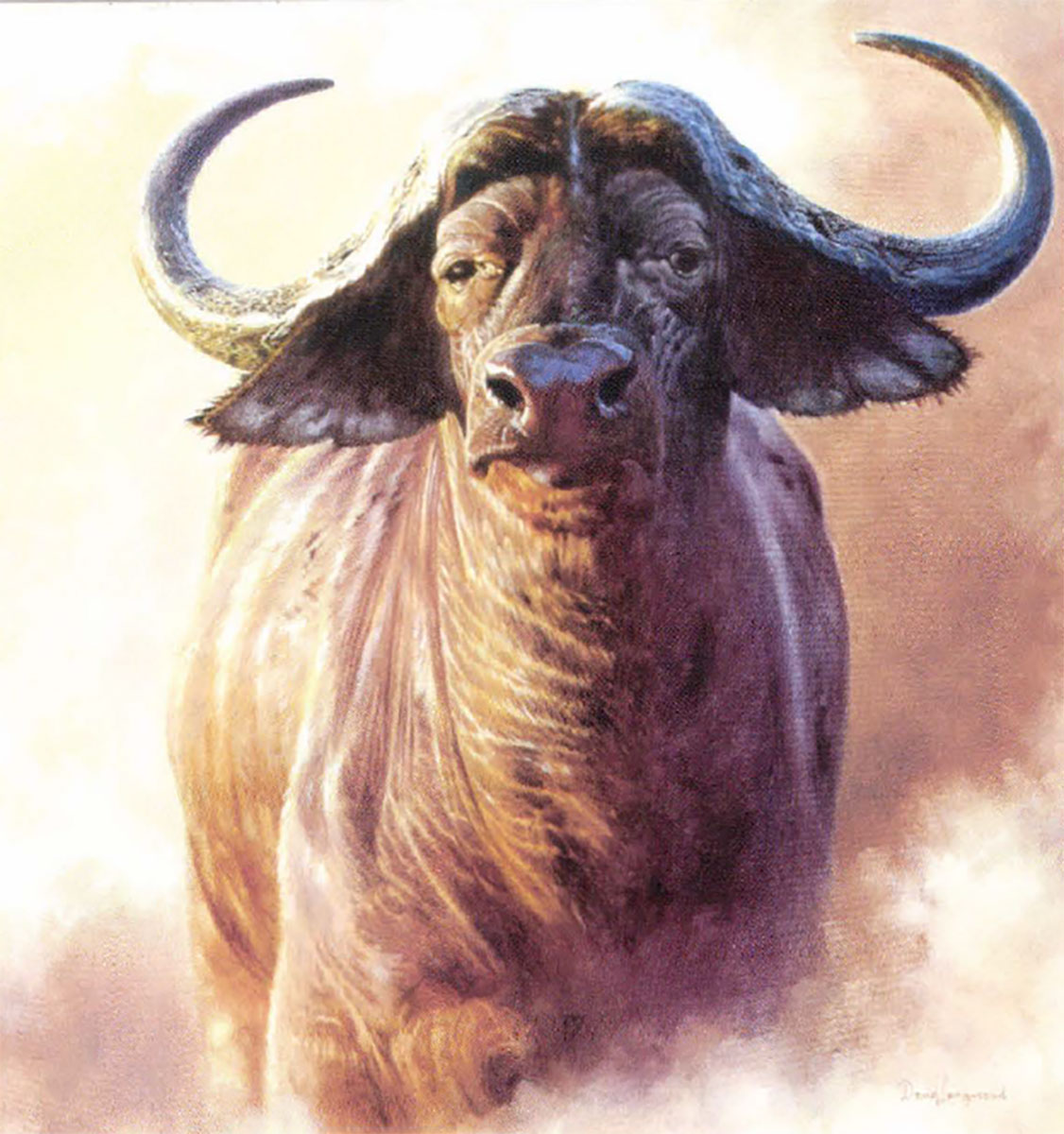

Over his long career, Bwana’s fierce vitality and great strength saved him more than a few times in serious entanglements with dangerous game. Cottar’s bullet once failed to stop the charge of a bull elephant in a thorny rendezvous. The enraged tusker grabbed Cottar and threw him into some bush, then unaccountably broke off the attack. Bwana escaped with a few broken ribs. Another time a buffalo knocked him down and gored him. Bwana lay on his back in the dust, while the buffalo shoved him along the ground with its horns, trying to finish him off. Cottar got one foot on each side of the bull’s neck and bracing his legs, he let the animal push him around until he could lever another shell into his .405 Winchester.

Although Cottar later suffered a stroke that partly paralyzed his left side, he continued to hunt with incredible energy for another 20 years. He also endured regular bouts of blackwater fever, an advanced and often deadly form of malaria. Doctors warned him that blackwater would kill him. Cottar ignored their warnings, convinced his end would come not from disease, but in the jaws of a lion. Elephant, buffalo and leopard had tried to kill him, and they had failed. He had not been horned by a rhino, but he dismissed old faru as being too ugly and too stupid to kill him. Although he had shot more than fifty lions, he was certain that one day a tawny cat would spring upon him from ambush when he least expected it. Bwana feared nothing on earth, yet he believed his days would end in a flurry of fang and claw, and he would die in writhing agony beneath the equatorial sun. Down the dangerous safari road, Cottar’s gloomy prediction turned out to be off the mark, but not by much.

During the monsoon rainy seasons in Africa, Bwana often returned to America to promote his safaris. In 1940 it seemed the gods had smiled when he landed a rich contract for a lecture tour across the US. Cottar needed spectacular film for his tour, and with his eldest son Bud, he headed for Barakitabu (Difficult Road) in Masailandto set up campi at their favorite spot beside a shallow stream-crossing.

One morning as they hunted the green foothills of the Loita Range, they surprised an old rhino, which immediately charged. Bud fired, wounding the beast, which veered away into dense brush. As his son pursued the rhino, Charles waited behind in the glade. All of a sudden the screech of tick birds pierced the stillness. Knowing the birds’ cries signaled the presence of a rhino or buffalo, Charles quickly unshouldered his heavy wooden tripod. The brush crackled like gunfire as an angry rhino tore out of the thorns looking for trouble. It paused briefly, its head held high, its long horns tilted back like lances at Bwana’s mid-section. Charles kept his eye to the viewfinder and cranked away. As he rolled off the film, the rhino charged, boiling through the dust. It was exactly the kind of dramatic footage he so badly needed. Charles figured he would film until the last one-hundredth of a second, then throw up his big .405 Winchester and drop the beast with a solid bullet in the brain. In worst case he could jump aside as the clumsy faru brushed past in his blind charge. When the thundering beast was on him, Cottar fired at point-blank range. The bullet struck muscle and bone, but the long horn now near the ground before the moment of impact, stooped upwards, ripping Bwana’s thigh. The rhino’s two-ton impact knocked the big man down, just as faru fell mortally wounded across Cottar’s legs. Yet the battering rhino had failed to loosen Bwana’s grip on his rifle. Pinned down by the great thrashing body, Cottar rammed his rifle into the rhino and fired several more rounds.

Bud heard the gunshots and sprinted back to his father. He saw where the horn had opened Bwana’s leg and passed through and artery. Bud fashioned a tourniquet to staunch the blood pumping from his father’s thigh. Bwana’s sun-shot eyes calmly gazed at a spiral of vultures with wings razoring the air, their shadows swooping doom over his tanned face. Cottar impatiently motioned toward the gunbearers who were tying a tarpaulin to shade him.

Mortally wounded, Charles commanded, “Tell them to stop. It’s no use. I’m done for. Roll it back.”

As he lay on Masailand’s baked black-cotton soil, he fixed his blue eyes on the sky above Cottar Country. One hour later the 66-year-old hunter had bled to death.

On a Sunday afternoon Bwana’s many friends paid their last respects at Nairobi’s Forest Cemetery. His loyal African safari crews were there, too, and none had dry eyes. The kali old hunter had gone to meet his god Ngai on the frozen jagged peak of Mount Kenya.

Long after his death, Charles Cottar’s legend lives on in the safari world. The dynasty he founded is now in its fifth generation. His eldest son Pat (“Bud”) followed in his father’s footsteps, accompanying the Duke and Duchess of York as well as renowned wildlife photographers Martin and Osa Johnson, on their early safaris in Kenya. His middle son Mike was thought by colleagues and clients to be the finest hunter of his time. Among his noted clients was Woodworth Donahue, American dimestore heir. In July 1941, during a safari on the western Serengeti plains, Mike was charged by a buffalo which he shot at close range. In an incident which paralleled the death of Bwana Charles, the momentum of the wounded buffalo carried it forward, and it fell on Mike. The talented hunter died soon afterward of a ruptured spleen. Ted, the youngest son, left Africa to live in California, but occasionally returned to hunt throughout the 1950s.

Long after his death, Charles Cottar’s legend lives on in the safari world. The dynasty he founded is now in its fifth generation. His eldest son Pat (“Bud”) followed in his father’s footsteps, accompanying the Duke and Duchess of York as well as renowned wildlife photographers Martin and Osa Johnson, on their early safaris in Kenya. His middle son Mike was thought by colleagues and clients to be the finest hunter of his time. Among his noted clients was Woodworth Donahue, American dimestore heir. In July 1941, during a safari on the western Serengeti plains, Mike was charged by a buffalo which he shot at close range. In an incident which paralleled the death of Bwana Charles, the momentum of the wounded buffalo carried it forward, and it fell on Mike. The talented hunter died soon afterward of a ruptured spleen. Ted, the youngest son, left Africa to live in California, but occasionally returned to hunt throughout the 1950s.

In turn, Mike Cottar’s only son, Glen, became a white hunter in 1956 during the glorious heyday of safari. For the next forty years he pioneered expeditions into remote reaches of East Africa, Botswana, Zaire and Sudan. With his wife Pat , he developed tented photographic camps in some of the finest big game country. Glen died in 1996. Today, his only son, 36-year-old Calvin Cottar, maintains the fine traditions of Africa’s First Family of Safari. His firm, Cottar’s Safari Service, is named after that of his famous great-grandfather.

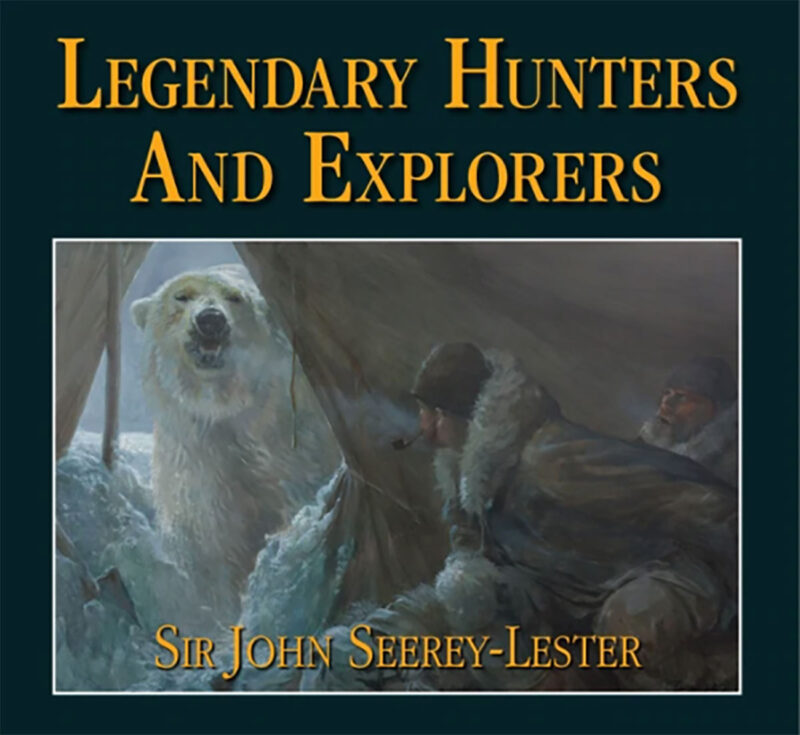

Finishing the final book in the iconic Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers is the epitome of Sir John Seerey-Lester’s spirit. Filled with over 120 paintings and 45 descriptive chapters, the new 200-page book relives the compelling stories of 25 acclaimed hunters and explorers.

Finishing the final book in the iconic Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers is the epitome of Sir John Seerey-Lester’s spirit. Filled with over 120 paintings and 45 descriptive chapters, the new 200-page book relives the compelling stories of 25 acclaimed hunters and explorers.

Amid his fight against cancer, Sir John Seerey-Lester was working tirelessly on his final book of the Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers, when he passed away in May of 2020. He is survived by his wife and fellow artist, Suzie Seerey-Lester, who carries his torch with vigor and pride. Buy Now