But of all Portland’s personalities, Ruth Leupold was very likely the best known.

In 1991, Ruth Leupold passed away in Portland at the age of 89. During her lifetime, Portland had its share of notable personalities — such as famed photographer/naturalist William L. Finley who used his friendship with Teddy Roosevelt to establish some of the most important wildlife refuges in the West, and writer/activist John Reed who envisioned a socialist America and was ultimately buried in the Kremlin.

But of all Portland’s personalities, Ruth Leupold was very likely the best known. She was involved in much of what went on in Portland for 50 years, but was primarily recognized for her role in founding the first youth orchestra in the United States, the Portland Junior Symphony.

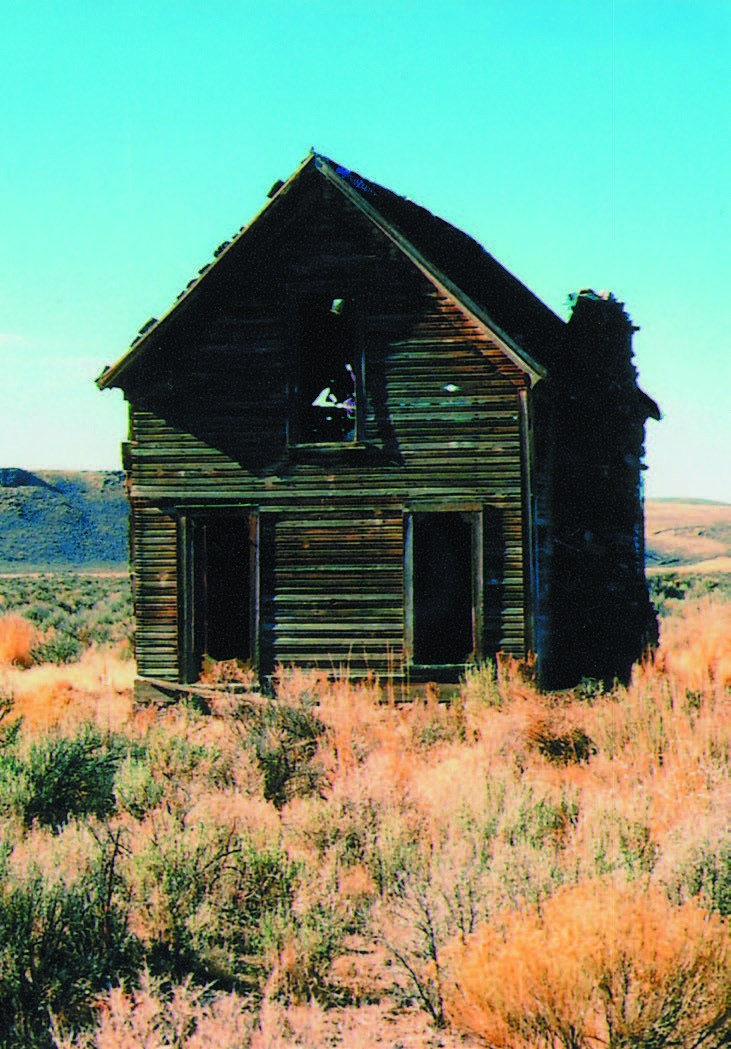

Ruth’s maiden name was Ruth Cowdin Saunders. As a child she was raised in a section of the state commonly known by Oregonians as “out of Burns.” The people that lived, or still live there, have always been something special to other Oregonians. Very simply, there wasn’t and isn’t a more demanding place in the state to live from one week to the next. It is vast, remote, harsh — searing hot in summer, 30-below zero in winter. Just sage, volcanic rock and space. A few ranch buildings still stand in which people were killed by Indians, and there are old mines worked by Chinese labor. The entire region is a continuous seep of history.

Ruth lived there as a little girl. The skeleton of her family’s bleak homestead remains erect. You pass it going down to Winnemucca, Nevada. It is a lonely place today; it’s hard to imagine little girls lived there in 1912. But in that year, her mother dead from TB, her father traveling the West tuning pianos, she and a younger sister went to live with their uncle Al in his tiny cabin at Virginia Gap about 40 miles from Burns. The girls arrived in mid-winter, just before Christmas, on a sled. Interestingly, uncle Al was a dedicated Socialist with a strong dislike for other people.

Ruth Leopold grew up in this tiny log home at Virginia Gap, which in the early 1900s was a vast, desolate region in northeastern Oregon.

In addition to uncle Al, Virginia Gap seemed to have a number of odd characters. A drunk neighbor took what he thought was quinine for a cold and it was actually strychnine for poisoning coyotes. He was crawling for help when he died. Another neighbor succumbed to a rattlesnake bite.

Ruth eventually returned to Burns where she lived most of her life. As a young woman attending school in Burns, Ruth’s remarkable character and talents were beginning to become evident. Among other things, she took violin lessons from Mary V. Dodge. She also developed a strong devotion to deer hunting. While in Burns, she was included in the annual deer camps in the surrounding mountains. Most years she was successful in shooting large bucks.

In 1918, Ruth’s father made a deal with Mary Dodge and her husband, Mott, to move from Burns to Portland and have Ruth live with them. Mary Dodge needed a pianist as an accompanist for her violin players and hired young Marcus Leupold. Fate played a part in the meeting of a deer hunter and a pianist, a union would benefit untold numbers of sportsmen in the years to come.

Back in 1907, what would become Leupold & Stevens, Inc. was founded by Fred Leupold and Adams Voelpel. They repaired surveying instruments, then expanded into the manufacture of these instruments. In 1914, a young inventor, John C. Stevens, joined the company with his new water-level recorder. It was highly successful and the firm grew steadily from that point. Also that year, Marcus Leupold decided to join the firm rather than pursue a career as a concert pianist.

It is important to note that none of the Leupolds or Stevens were outdoorsmen. When Ruth and Marcus married, she certainly changed that. Family members recall that it was she who organized the first of what became the annual deer camp near Burns for company officials. She showed the men the way by planning the camps, hunting hard and frequently shooting the largest bucks.

After a few years, the autumn deer hunt became one of the most keenly anticipated events for the heads of Leupold & Stevens. Marcus Leupold in particular became an avid hunter.

The family story has it that during the late 1930s, he and Ruth were out together on a cold morning. Ruth had shot a good buck the day before. Soon after sunrise, the largest mule deer that Marcus had ever seen stepped out into the open. It was an easy shot, but his scope was fogged up and he missed.

As the deer raced away, he reportedly muttered: “I can make a better scope than this!”

During the next few years, Ruth made sure he remembered that statement. At her urging, he set about making that better scope.

Of course, the rest is history. A lot of us use Leupold scopes today. We can thank Ruth. She used them herself, right up to her last years, on her favorite rifle, a Model 54 Winchester in 270.

In Great Hunting Rifles, firearms expert Terry Wieland leads the reader on a journey through the history of some of the most exquisite rifles made in the twentieth century. Buy Now

In Great Hunting Rifles, firearms expert Terry Wieland leads the reader on a journey through the history of some of the most exquisite rifles made in the twentieth century. Buy Now