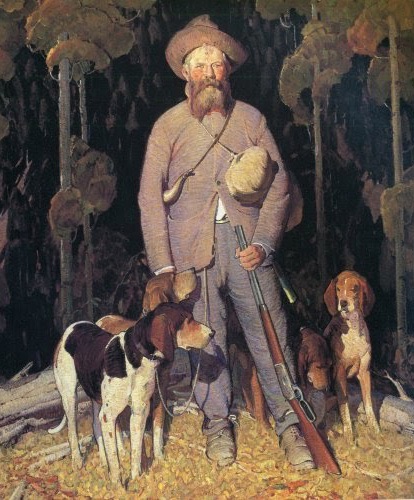

Noted Taos School artist William Herbert “Buck” Dunton created this portrait of Lilly: Big Game Hunter, circa 1921.

After the presidential bear hunt, Lilly went back to Texas and soon drifted across the border into Mexico, continuing his pursuit of black bears and cougars with a vengeance. He gained even more renown hunting the few remaining grizzlies in the Sierra Madre Mountains in western Coahuila. Later still, he drifted back across the border into New Mexico where he settled in the Gila Wilderness and continued his predator control work on bears and panthers for ranch owners and the government. He is credited with killing the last wild grizzly in the vast Gila Wilderness. By 1912, he was earning $75 a month as a hunter and trapper for the Apache National Forest in Arizona. Between 1916 and 1920 he was employed full-time by the U.S. Biological Survey.

Lilly stood five feet, nine inches tall and weighed 180 pounds. He was known for his strength and stamina. He always wore a full beard and was said to possess gentle blue eyes that perpetually held a faraway look in them. He spent Sundays reading his bible and he never smoked, drank or used profanity. He maintained a lifelong preference for sleeping and living outdoors, adapting well to the “strenuous life” that Roosevelt loved to talk about. He was well known for always wearing brogan shoes in any weather and, even in the dead of winter he seldom wore heavy clothes when he was on the track of a bear or panther. He remained in amazingly good health right up until the time of his death at 80 years of age.

Lilly was eccentric, tough as nails, and like many of his contemporaries, almost impervious to bitter cold, bad weather and other harsh conditions that living outside demanded. When his hounds got on the trail of a bear or panther, he never gave up until he killed his quarry. If he happened to tree a lion or bear late Saturday evening, he would make his dogs keep the animal at bay until Monday morning. He was known to sometimes track certain animals for hundreds of miles and days at a time.

Perhaps he had a little John Muir in his system for he was always exploring, always looking over the next hill or mountain for new vistas, but hunting was in his blood and soul and kept him going through snowstorms and blistering heat. Lilly loved his hounds more profoundly than he loved most humans. He used mostly southern Catahoulas and coonhounds. In 1925, near Sapillo Creek, New Mexico, Lilly wrote an epitaph on the box in which he buried one of his most prized hounds: “Here lies Crook, a bear and lion dog that helped kill 210 bear and 426 lion since 1914, owned by B. V. Lilly.”

No one knows the exact number of animals Lilly killed during his lifetime, but it has been estimated that he brought down between 600 and 1,000 mountain lions and at least that many bears.

Ben Lilly poses with his pack of hounds at G. O. S. Ranch headquarters about 20 miles north of Silver City, New Mexico. Photo circa 1920s.

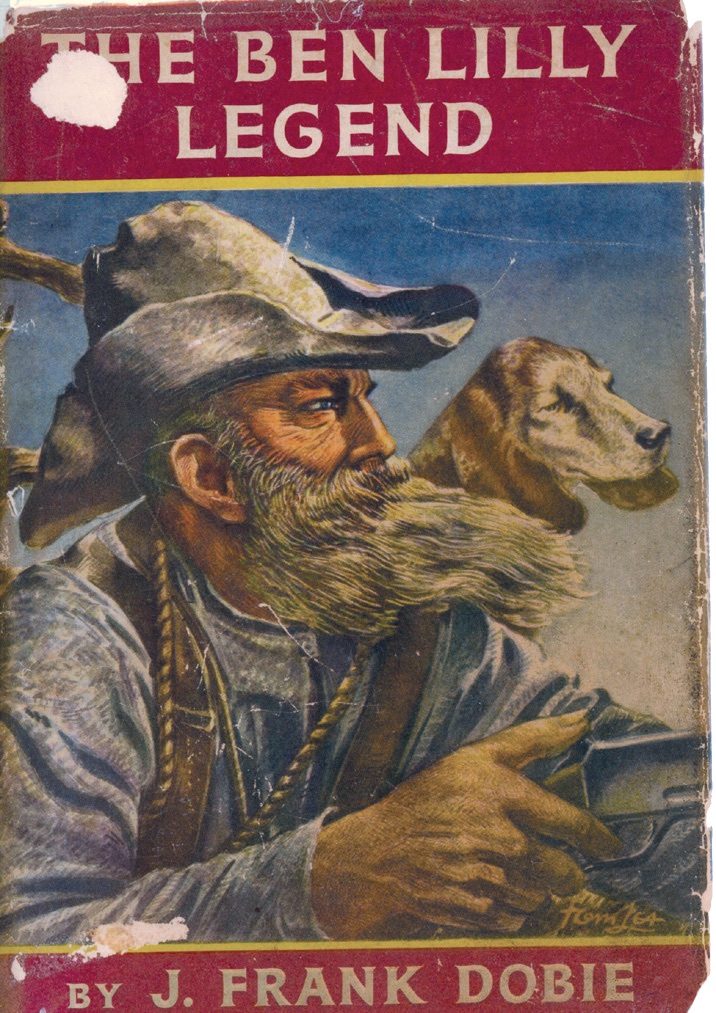

My great uncle, J. Frank Dobie of Texas (1888-1964), met Ben Lilly at a Cattleman’s Association meeting in El Paso in 1928 where Lilly had been invited to speak. Dobie was so intrigued with what he found to be a “true American original” that he sat down with him right away and began recording bits and pieces about Lilly’s life. He continued collecting stories and information about Lilly for the next 20 years.

In 1950, he published his classic book, The Ben Lilly Legend. In the book, Lilly is quoted as saying: “My reputation is bigger than I am. It is like a shadow when I stand in front of the sun in late evening.”

The author’s copy of the original 1950-issue of The Ben Lilly Legend.

No doubt, Lilly’s legend grew to be larger than life. The master hunter, writer and archeologist Frank C. Hibben (1910-2002) shared a three-day hunt with Lilly in 1933 when the aging hunter was 77. Hibben later wrote an article about that memorable experience in the May 1948 issue of Outdoor Life. One of the tall tales he included in that story mentioned Lilly’s amazing marksmanship.

“Mr. Lilly of legend could shoot a treed lion through the paw in the top of a pine tree and then drill it through the heart as it fell, end over end, through the branches to the ground.”

Frank Hibben was duly impressed with the old hunter and always cherished that experience.

Ben Lilly died at age 80 on December 17, 1936, after a short illness, on a ranch near Silver City, New Mexico. He is buried in the iconic Memory Lane Cemetery in Silver City. His tombstone bears the simple inscription: “Lover of the Great Outdoors.” In 1947, a bronze plaque was erected by his friends on Bear Creek, in Pinos Altos, New Mexico to honor his memory.

A true American original, Ben Lilly heard the call of the wild. He heeded that call and never looked back.